CHAPTER 57 Arthroscopic-Assisted Osteotomy for Intra-articular Malunion of the Distal Radius

Rationale and Basic Science Pertinent to the Procedure

Classically, management of a young patient with a step-off in the distal radius has been panarthrodesis. Several pioneer surgeons, such as Saffar,1 Fernandez,2 and others,3–8 opened the door to the possibility of cutting again the displaced fragments and reducing them in anatomical position. The gold standard for the most common sagittal step (anteroposterior) is to do the osteotomy through a dorsal route partly under fluoroscopy guidance.4,5,7,8 For volar shearing type malunions, the joint is approached volarly, the external callus is removed, and with an osteotome directed toward the joint, the fragment is slowly cut away, with the hope that the osteotome follows the original fracture line.5,6,8 All these procedures and others can be grouped under “outside-in osteotomy techniques.”

Good results have been reported with outside-in osteotomy techniques, but fears of devascularization and inaccurate reduction exist. Fernandez2 considered the technique appropriate only for single line fractures, although Gonzalez del Pino and Ring4,5 used it for the more complex four-part fractures.

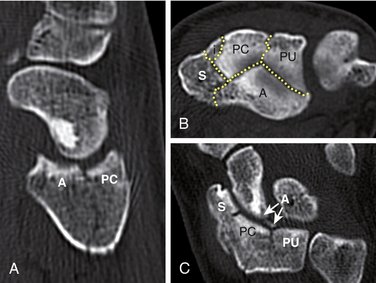

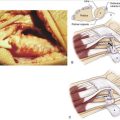

In my experience with outside-in osteotomy techniques, the main problem I had encountered was the difficulty having visual control of the step-off before the osteotomy, which became an “impossible” feat when the fragment was “reduced” as the joint space closed. One then had to rely on fluoroscopy (an unreliable method),9 and on palpation with a Freer elevator. Another problem was that sometimes the step-offs did not have a linear trace amenable to a simple cut, but rather a complex irregular shape (Fig. 57-1). To obtain better visual control, a very aggressive capsular release is necessary. This aggressive capsular release may increase the risk of avascular necrosis of the ostetomized fragments, virtually contraindicating outside-in techniques.

Bearing in mind these limitations, we sought a method for assessing the status of the articular cartilage in the area of malunion, which at the same time allowed us to identify the fracture line accurately. This chapter outlines our present experience with a method to perform the osteotomy under arthroscopic guidance from “inside-out.”10

Indications

Any candidate for an outside-in osteotomy correction1–7 can be eligible for an arthroscopic-guided osteotomy. Absolute indications are a malunion in the coronal plane (shearing-type fractures) causing secondary carpal subluxation and any fracture with a step-off of 2 mm or more, whether or not the patient is symptomatic. Some authors11 believe that step-offs of just 1 mm also can be symptomatic, and it seems sensible in young patients with an intrafacetary step-off to go ahead with the operation. Low-demand patients or silent areas (e.g., the interfacetal sulcus) are better served by a conservative approach.

Timing is important, and delaying the operation would have a negative impact on the outcome in two ways. First, healthy areas of cartilage would wear out, particularly in intrafacetary step-offs.2,12 Second, the operation would be technically more difficult, and the reduction obtained would be less accurate; this is because the gap would be filled with mature bone (rather than scarred bone and granulating tissue), making it more difficult to achieve reduction and to close the gap. Additionally, overzealous resection of tissue in the gap may cause narrowing of the radius in the frontal plane (see Fig. W9-5 online) causing ulnar translocation of the carpus.

Although my experience is limited to malunions less than 3.5 months old, I cannot see any contraindication in older malunions, provided that the cartilage is preserved. Surgical tactics vary slightly for older malunions (see later). Delaying the operation in the hope that some cases may not be symptomatic does not seem reasonable because midterm osteoarthritis has been shown to occur in most intra-articular malunions in young individuals.13,14

Surgical Technique

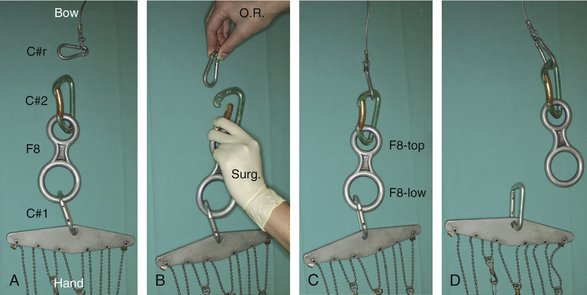

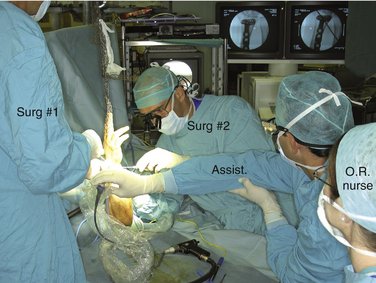

The surgical technique is more cumbersome and complicated than the average wrist arthroscopy.10 First, it requires an open exposure of the distal radius for plate fixation of the fragments in addition to the arthroscopic-aided osteotomy. Second, it requires alternating the hand from a suspended position to flat on the operating table. We use a custom-made system that allows easy fastening and release of the hand to and from the bow (Fig. 57-2).10 Third, fluoroscopy is used periodically during the procedure, which is facilitated by placing the hand flat. The osteotomes and probes that are used need to be sturdier than the average arthroscopic instruments (Fig. 57-3). Finally, the assistance of another experienced surgeon is integral to the procedure (Fig. 57-4). It is important that everyone on the surgical team is prepared and familiar with their assigned role to diminish the operative time because the whole procedure needs to be done in less than tourniquet time. It is helpful for the surgeon to preplan the osteotomies beforehand based on a review of the preoperative x-rays and, if possible, the original fracture films. I have found a good-quality preoperative computed tomography scan to be invaluable because the intraoperative view of the joint disruption can be quite misleading (see Fig. 57-1).

The key of the whole operation is to perform the arthroscopy without infusion water, which we have called “dry arthroscopy.”15 This dry technique prevents the constant vision losses owing to water escaping through the portals that we experienced with the classic (wet) technique and that made us abandon our initial attempts to perform the osteotomy. The dry technique has two additional advantages: There is no risk of massive fluid extravasation causing compartment syndrome, and the open part of the operation is done without the tissues being infiltrated with water. Not infusing water engenders a new set of difficulties secondary to vision loss owing to splashes and blood staining. Numerous tricks are available to deal with these hindrances, and these are discussed separately later in this chapter.

Osteotomy

The arm is exsanguinated and stabilized to the table with a strap at the arm. In early malunions, the procedure is started by preparing the proposed site of plate fixation with the arm lying on the hand table. A limited volar-ulnar incision is used for a volar shearing type of intra-articular malunion. A limited Henry approach is used in cases of a malunited radial styloid fragment or multifragmented malunion. A plate is preplaced and held in position with a single screw through its stem. Then the arthroscopic part begins.

The standard 3,4 and 6R portals are developed. Transverse 1-cm skin incisions are preferred on the dorsum of the wrist because they heal with a minimal scar. To avoid lacerating any nerve or tendon, a superficial skin incision is made with a no. 15 blade. A hemostat is used to widen the portal to permit the smooth entrance of the osteotomes and other necessary instruments. Apart from dorsal portals, a volar radial (VR) portal is always used. If a Henry type of incision is planned, the portal is developed as recommended by Levy and Glickel16; otherwise, we follow the techniques of Doi and coworkers11 or Slutsky17 (Fig. 57-5). The quality of the articular cartilage over the adjacent scaphoid and lunate is assessed along with exploration of the midcarpal joint if there is any doubt about the integrity of the interosseous ligaments.

When major cartilage destruction has been ruled out, and the fragments to be mobilized are defined, the scope is moved to the 6R portal, and the 3,4 and VR portals are used for instrumentation. For cutting the fragments, we use periosteal elevators that are commercially available for shoulder surgery (Artrex AR-1342-30° and AR-1342-15°; Artrex, Naples, FL). These elevators have a width of 4 mm and are strong enough to cut the fragments by gently tapping with a hammer. More recently, we have incorporated straight and curved osteotomes (Artrex AR-1770 and AR-1771), which can be helpful because their different shapes are ideally suited to following the irregular shape of the fracture lines. To avoid the risk of lacerating extensor tendons when introducing the “osteotomes” through the 3,4 portal, the blade of the osteotome should be introduced parallel to the tendon under direct visual control and then rotated while inside the joint. Gentle maneuvers are necessary when hammering from dorsal to volar because there is a risk of cutting flexor tendons if plunging volarly or extensor tendons when doing the reverse maneuver.

Often scar and new bone formation between the fragments impede reduction. This early granulation tissue should be resected with the help of small curets or burs introduced through the portals. When the reduction is acceptable (Fig. 57-6), one surgeon maintains the position of the fragments, while the assistant inserts the distal locking pegs in the plate. This step may be difficult because the flexor carpi radialis and digital flexors are under tension (owing to the traction) and impede insertion of any ulnar screws in the plate. This step is facilitated by backing off the wrist traction sufficiently to allow tendon retraction by insertion of a Farabeuf type of retractor. A compromise must be made to prevent a complete collapse of the radiocarpal space.

FIGURE 57-6 Correction of a step-off in the same patient as shown in Figure 57-1. Right wrist, the arthroscope is in 6R; at the very far upper left corner is the styloid. A, Step-off on the scaphoid fossa. B, The osteotome (entering the joint through the volar-radial portal) is separating the malunited fragments. C, Corresponding view after reduction.

(From del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, et al: Correction of malunited intra-articular distal radius fractures with an inside-out osteotomy technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006; 31:1029-1034; with permission from the American Society for Surgery of the Hand.)

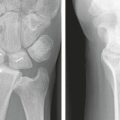

When the articular fragments have been secured under arthroscopic control, the hand is laid flat on the operating table, and the rest of the screws are inserted in the plate. The type of fixation depends on the configuration of the malunion. In one case, we used a single screw to secure the volar-ulnar fragment. In another, a 2.7-mm buttress plate was used to stabilize a styloid fragment. In the most common situation in which there are four or more fragments, a plate with locking distal pegs is preferred (DVR; Hand Innovations, Miami, FL) (Fig. 57-7).

FIGURE 57-7 A, Preoperative x-ray of the same patient in Figures 57-1, 57-6, and 57-8 (depressed fragments highlighted by black dots). B, Restoration of the articular line (6 weeks).

(From del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, et al: Correction of malunited intra-articular distal radius fractures with an inside-out osteotomy technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006; 31:1029-1034; with permission from the American Society for Surgery of the Hand.)

The hand is suspended again under traction for a final inspection of the articular surface. The joint is irrigated with 10 to 30 mL of saline introduced through the scope’s side tube, and a shaver is used to remove all the debris. Fluoroscopy can be used repeatedly throughout the procedure by releasing the hand from the traction bow (see Fig. 57-2). Some authors find it easier to perform wrist arthroscopy with the hand lying flat on the table, but we have no experience with this technique.18

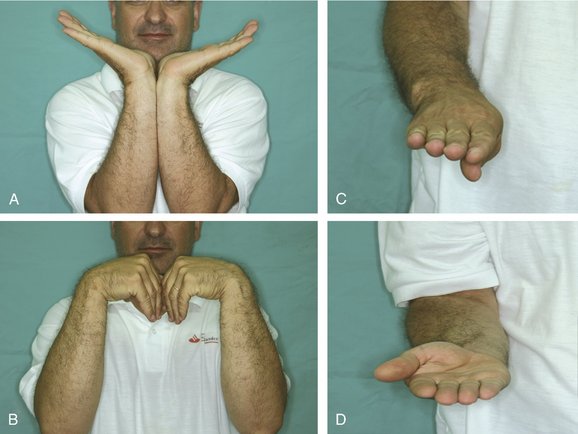

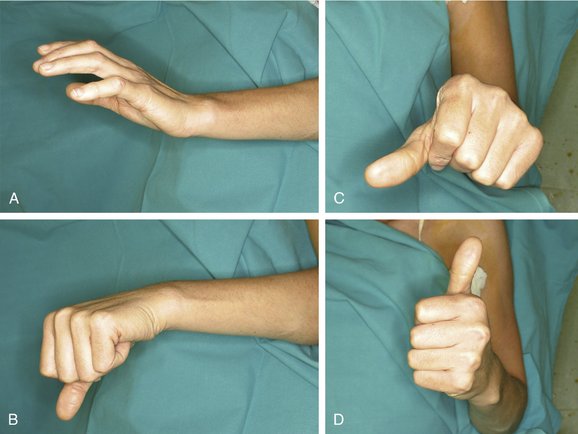

The portals are closed with paper tape or a single stitch, and the wrist is placed in a removable splint. In all our cases, the fixation was sufficiently stable to start protected range of motion on the first postoperative visit (48 hours) (Fig. 57-8).

Modifications to Improve Vision When Using the Dry Technique

The dry technique introduces a new set of difficulties derived from vision loss secondary to splashes of blood or soft tissue debris that may stick to the scope tip. Removing the scope and wiping off the lens with a wet sponge is efficacious but time-consuming. Poor vision quality or being immersed in a “red sea” may make the surgeon abandon this technique, which has a lot to offer. Based on our experience with more than 100 dry wrist arthroscopies, we have found the following technical tips helpful15:

inch ×

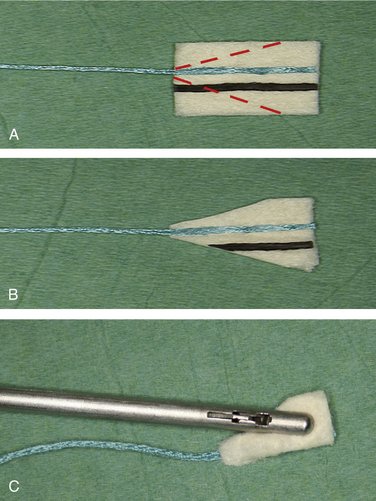

inch ×  inch; Ref 800-04003, size 1 inch × 1 inch [25 × 25 mm]; Neuray; Xomed, Jacksonville, FL). The small patty can be rolled and directly introduced into the joint by a grasper. The large patties have to be slightly modified by cutting them into the shape of a triangle, which facilitates removal from the joint. If the patties become entangled, they can be removed by pulling on the tail or by retrieving with a grasper (Fig. 57-9).

inch; Ref 800-04003, size 1 inch × 1 inch [25 × 25 mm]; Neuray; Xomed, Jacksonville, FL). The small patty can be rolled and directly introduced into the joint by a grasper. The large patties have to be slightly modified by cutting them into the shape of a triangle, which facilitates removal from the joint. If the patties become entangled, they can be removed by pulling on the tail or by retrieving with a grasper (Fig. 57-9).

FIGURE 57-9 A and B, To dry out the surgical field, the neurosurgical patties have been modified (A), and the squared tail part has been cut to facilitate its removal (B). C, The patty is rolled and introduced into the joint with a grasper. To prevent the patty from entangling or breaking inside the joint, the grasper (not the tail) is used to retrieve it. Breakage is not much of a problem because the remaining segment can be retrieved easily with the grasper.

(From del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Regalado J, et al: Dry arthroscopy: surgical technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2007; 32:119-123, with permission from the American Society for Surgery of the Hand.)

Results

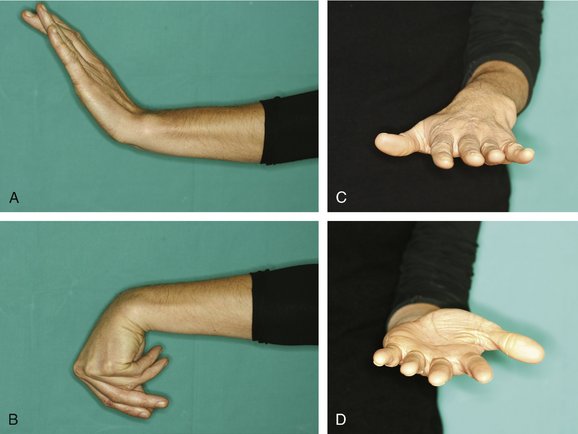

The technique presented here is drawn from experience in five patients with nascent intra-articular malunions of short duration (5 weeks to 3.5 months) with a follow-up of 6 months to 2.5 years. Two patients had a single fragment mobilized (one anteromedial fragment, one styloid fragment) with severe functional limitation (Fig. 57-10). The other three patients had two or more fragments mobilized (all had C31 fractures of the AO classification). Gaps of less than 1 mm were unavoidable after the operation because of a preexisting loss of cartilage and early granulation tissue, but intra-articular steps were reduced to 0 mm (from a maximum of 5 mm).

It may be argued that fragments may be more easily defined early on by simply breaking the external callus. Based on the experience of our group and others, however, impacted cartilage containing fracture fragments is soundly healed by 3 to 4 weeks and needs to be redefined with the use of an osteotome.3,19 Piecemeal fragmentation can occur if the mobilization is not done carefully. Herein lies the main advantage of the procedure: The arthroscope allows us to follow the exact line of chondral fracture under magnification and to restore the anatomy of the cartilaginous surface. Additionally, the risk of avascular necrosis of the mobilized fragments is minimized as nominal interference with the soft tissue connections of the fragments occurs. Finally, the capsular ligaments are not violated (Fig. 57-11). All these facts together with rigid fixation allow rapid healing and permit immediate mobilization (Fig. 57-12).

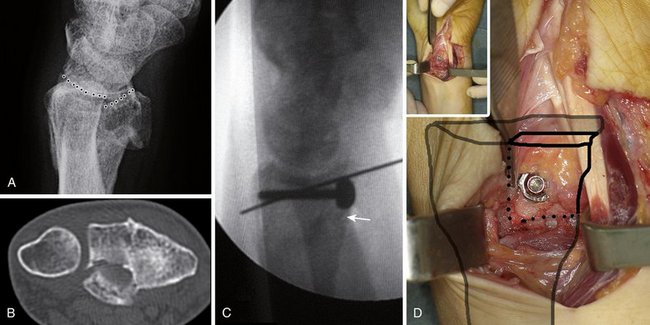

FIGURE 57-11 A and B, A displaced volar-ulnar fragment involving the radiocarpal and the distal radioulnar joint was evident. This single fragment was responsible for minimal range of motion and loss of supination. C, The malunited fragment was reduced provisionally with a Kirschner wire, and then, with the hand lying on the table, a 2.7-mm screw with a washer was used for fixation. (Fluoroscopic control; arrow points to the reduced volar cortex). D, Notice minimal disturbance of the soft tissue attachments around the fragment at the end of the operation.

1 Saffar P. Treatment of distal radial intra-articular mal-unions. In: Saffar PH, Cooney WPIII, editors. Fractures of the Distal Radius. London: Martin Dunitz, 1995.

2 Fernandez DL. Reconstructive procedures for malunion and traumatic arthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;24:341-363.

3 Marx RG, Axelrod TS. Intraarticular osteotomy of distal radius malunions. Clin Orthop.. 1996;327:152-157.

4 Gonzalez del Pino J, Nagy L, Gonzalez Hernandez E, et al. Osteotomías intraarticulares complejas del radio por fractura. Indicaciones y técnica quirúrgica. Rev Ortop Traumatol. 2000;44:406-417.

5 Ring D, Prommersberger KJ, Gonzalez del Pino J, et al. Corrective osteotomy for malunited articular fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1503-1509.

6 Thivaios GC, McKee MD. Sliding osteotomy for deformity correction following malunion of volarly displaced distal radial fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:326-333.

7. Apergis E: Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the International Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand, Budapest, Hungary, June 13-17, 2004.

8 Prommersberger KJ, Ring D, Del Pino JG, et al. Corrective osteotomy for intra-articular malunion of the distal part of the radius: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 1, Pt 2):202-211.

9 Edwards CC2nd, Haraszti CJ, McGillivary GR, et al. Intra-articular distal radius fractures: arthroscopic assessment of radiographically assisted reduction. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:1036-1041.

10 del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, et al. Correction of malunited intra-articular distal radius fractures with an inside-out osteotomy technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006;31:1029-1034.

11 Doi K, Hattori Y, Otsuka K, et al. Intra-articular fractures of the distal aspect of the radius: arthroscopically assisted reduction compared with open reduction and internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1093-1110.

12 Wagner WFJr, Tencer AF, Kiser P, et al. Effects of intra-articular distal radius depression on wrist joint contact characteristics. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1996;21:554-660.

13 Knirk JL, Jupiter JB. Intra-articular fractures of the distal end of the radius in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:647-659.

14. Trumble TE, Schmitt SR, Vedder NB. Factors affecting functional outcome of displaced intra-articular distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1994;19:325-340.

15 del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Regalado J, et al. Dry arthroscopy: surgical technique. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2007;32:119-123.

16 Levy HJ, Glickel SZ. Arthroscopic assisted internal fixation of volar intraarticular wrist fractures. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:122-124.

17 Slutsky DJ. Clinical applications of volar portals in wrist arthroscopy. Tech Hand Upper Extrem Surg. 2004;8:229-238.

18 Huracek J, Troeger H. Wrist arthroscopy without distraction: a technique to visualise instability of the wrist after a ligamentous tear. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:1011-1012.

19 del Piñal F, Garcia-Bernal FJ, Delgado J, et al. Results of osteotomy, open reduction, and internal fixation for late-presenting malunited intra-articular fractures of the base of the middle phalanx. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:1039-1050.