CHAPTER 2 Arthroscopic and Open Anatomy of the Hip

Introduction

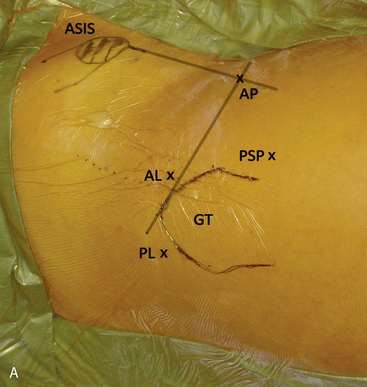

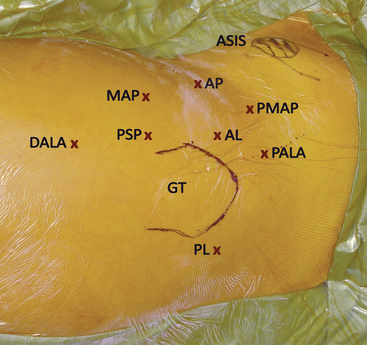

Several bony landmarks define the surface anatomy of the hip. The anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS) and anteroinferior iliac spine (AIIS) are located anteriorly, with the former being palpable. These structures serve as the insertion points for the sartorius and the direct head of the rectus femoris, respectively. Posterolaterally, two bony landmarks are palpable: the greater trochanter and the posterosuperior iliac spine. The greater trochanter serves as the insertion point of the tendon of the gluteus medius, the gluteus minimus, the obturator externus, the obturator internus, the gemelli, and piriformis. The posterosuperior iliac spine serves as the attachment point of the oblique portion of the posterior sacroiliac ligaments and the multifidus. During arthroscopic and open access to the joint, both of these landmarks are useful tools for incision planning, and, in combination with the anterior bony prominences, for initial orientation (Figure 2-1, A).

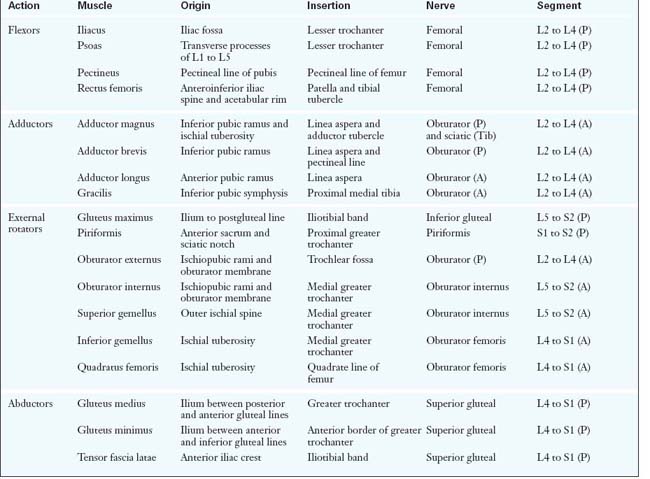

There are a total of 27 muscles that cross the hip joint. They can be categorized into six groups according to the functional movements that they induce at the joint: 1) flexors; 2) extensors; 3) abductors; 4) adductors; 5) external rotators; and 6) internal rotators. Although some muscles have dual roles, their primary functions define their group placement, and they all have unique neurovascular supplies (Table 2-1).

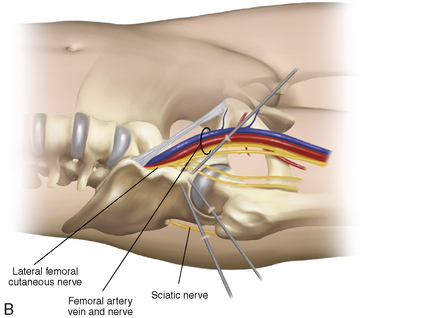

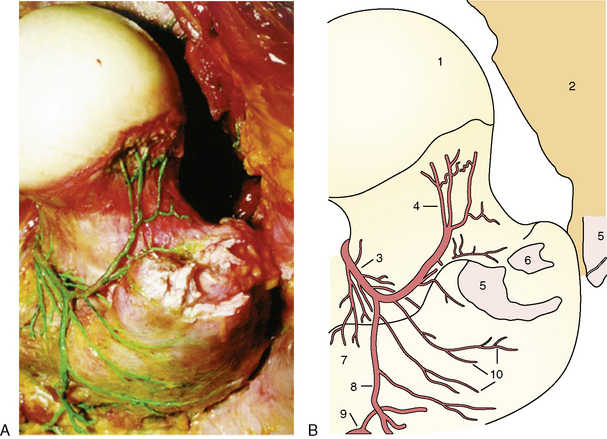

The vascular supply of the hip stems from the external and internal iliac arteries. An understanding of the course of these vessels is critical for avoiding catastrophic vascular injury. In addition, the blood supply to the femoral head is vulnerable to both traumatic and iatrogenic injury; the disruption of this supply can result in avascular necrosis (Figure 2-2).

Hip musculature

Abductors

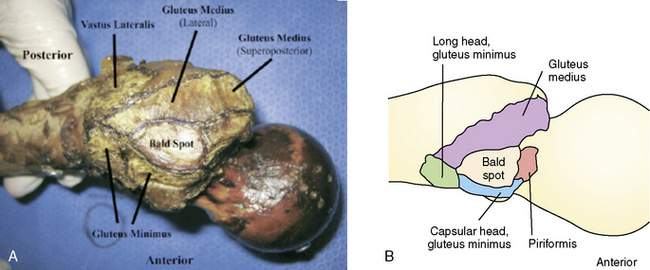

The abductors consist of the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles. Both of these muscles are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve (i.e., the posterior division of L5 to S2). The TFL and the iliotibial band also contribute to hip abduction. This action is only apparent with the hip in a flexed position, and the TFL and the iliotibial band are therefore considered secondary abductors. The gluteus medius, which is the primary hip abductor, originates at the posterior external table of the iliac wing. It is completely covered by the overlying gluteus maximus as it travels distally toward its insertion at the lateral and superoposterior facet of the greater trochanter (Figure 2-3, A). The gluteus minimus fibers run in close approximation to the lateral hip capsule, onto which some of the muscle may also insert. These fibers are often the first to be encountered during hip arthroscopy procedures when establishing the anterolateral portal. The gluteus minimus, which is responsible for 25% of abduction power, runs in the same plane deep to the gluteus medius. It inserts more anteriorly on the greater trochanter, and it has a separate long head component. Recent evidence suggests that a common cause of lateral hip pain may be tears of the hip abductor insertion and not simply trochanteric bursitis. These tears are referred to as rotator cuff tears of the hip. Anatomic restoration of the insertion of the torn gluteus medius can be achieved with standard arthroscopic technique in the recently described peritrochanteric compartment. When trochanteric bursitis does exist in isolation, it is most likely located at the posterior facet or the bald spot of the trochanter (see Figure 2-3, B).

External and Internal Rotators

The external rotators include the obturator internus, the obturator externus, the superior and inferior gemelli, the quadratus femoris, and the piriformis muscles (see Figure 2-3). These small but powerful musculotendinous units act synergistically to provide the external moments that are necessary to generate lateral and rotational activities. The piriformis is the common denominator of the external rotators, and it serves as an important anatomic landmark during both the posterior approach and the surgical dislocation of the hip.

Neurovascular supply of the hip

Vasculature of the Hip

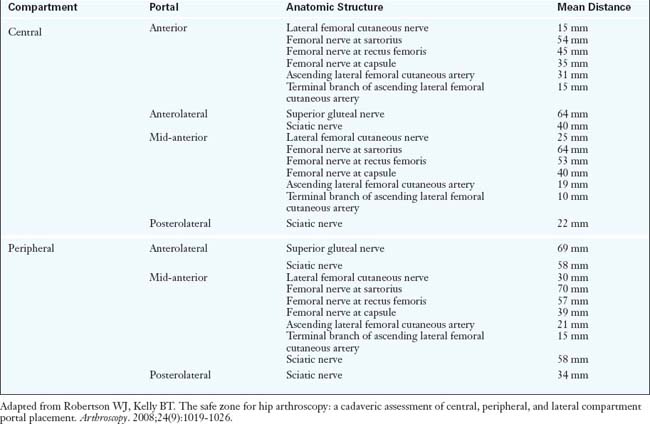

The common femoral artery is the first branch of the external iliac artery, and it traverses just anteromedial to the hip capsule as it travels distally. It is at high risk for damage during both arthroscopic and open anterior approaches to the hip. In fact, the traditional anterior arthroscopic portal is approximately 3.5 cm from the femoral neurovascular bundle (Table 2-2). During total hip arthroplasty (THA), femoral vessel injury and femoral nerve palsy have been described as arising from the incorrect placement of retractors, which can occur with all approaches to the hip. However, because the artery is a large, fairly superficial, and therefore readily palpable vascular structure, its exact location should be routinely identified and thus easily avoided.

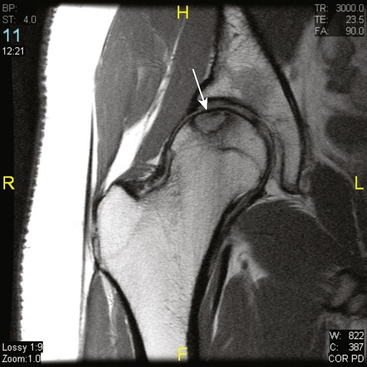

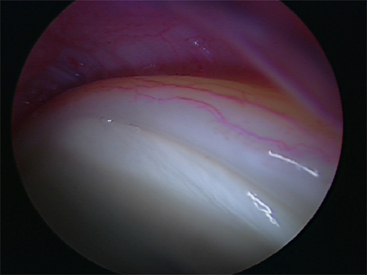

Therefore, the vessel that supplies the majority of the arterial supply to the head is the medial circumflex femoral artery, with varying contributions from the lateral circumflex femoral artery. These vessels branch off at the base of the femoral neck and then ascend toward the femoral head via the posterolateral and posteroinferior synovial retinacular folds (Figure 2-4, A and B). It is believed that disruption at this level (e.g., by a femoral neck fracture) poses the greatest risk for avascular necrosis. The lateral synovial folds, which contain the terminal branches of the medial circumflex femoral artery, can also be injured as a result of aggressive arthroscopic dissection (Figure 2-5) or open approaches. Therefore, they should be routinely identified and protected during peripheral compartment arthroscopy and during open joint-preserving hip surgery.

Arthroscopic anatomy of the hip

Surface Anatomy

An accurate understanding of the surface anatomy is crucial for anatomic orientation and initial trocar insertion. Typically, the outlines of the greater trochanter and the ASIS are drawn, followed by the intersecting horizontal and vertical lines from each point, respectively. With the use of these basic landmarks, the three most commonly used portals as described by Thomas Byrd—the anterior, anterolateral, and posterolateral portals—can be accurately placed (see Figure 2-1, B).

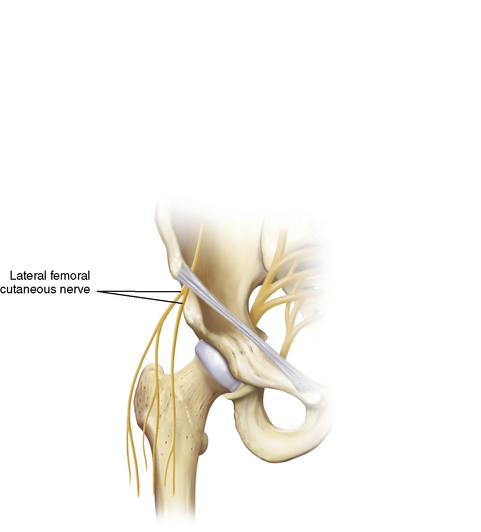

Anterolaterally, the arthroscopist should understand the course of the LFCN, which travels approximately 1 cm medial to the ASIS just below the epidermal layer and subsequently branches out in a fan-like distribution (Figure 2-6). Although the incidence of complications during hip arthroscopy is low, the LFCN branches are in close proximity to the anterior portals, and localized paresthesias of the thigh as a result of damage of this nerve are not uncommon. Although blunt trauma during portal placement can cause damage to the LFCN branches, the more likely culprit is inadvertent scalpel injury, which reiterates the importance of a careful skin incision.

The Arthroscopic Portals

The anterolateral portal is the workhorse of all of the arthroscopic portals around the hip. It is considered to be the safest portal, and it is therefore established first and “blindly” (i.e., with the assistance of fluoroscopy alone). It is useful for the visualization of the central, peripheral, and peritrochanteric compartments. To create an anterolateral portal, an initial superficial incision no deeper than the subcutaneous adipose tissue is made over the anterosuperior tip of the greater trochanter. A fascial band just posterior to the skin incision is commonly encountered, and it can be used as a reference mark. A sheathed blunt trocar or snap is used to pass through the adipose tissue, fascia, and muscle tissue to the hip capsule. The superior gluteal nerve lays approximately 4.5 cm superiorly to this portal (see Table 2-2). A spinal needle is then used to enter the hip joint, and this is followed by a guidewire and a trocar. After the surgeon has entered the joint space, the superolateral labrum, the acetabular articular cartilage, and the femoral head are vulnerable to iatrogenic damage. Therefore, blunt trocars are preferred. Finally, image intensification and the injection of saline can confirm the proper positioning of the intra-articular spinal needle. Subsequent portals are established with intra-articular arthroscopic guidance.

After the anterolateral portal is established, the anterior portal is typically the second and most difficult portal to establish. It allows for the observation of the anterior femoral neck, the superior retinacular fold, the lateral acetabular labrum, portions of the transverse acetabular ligament, and the ligamentum teres. Traditionally, this portal is placed directly at the intersection of the lines drawn vertically from the ASIS and horizontally from the greater trochanter. However, this approach involves the direct penetration of the origin of the rectus femoris tendon. It has been suggested that a resultant tendinopathy causes increased soreness in the anterior groin region. Therefore, a recent a trend has emerged with the anterior portal placed just distal and lateral to the traditional portal site: the mid-anterior portal (Figure 2-7). To establish any anterior portal, one must be careful to superficially avoid the LFCN and its branches. On deeper exploration, the surgeon should be familiar with the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery, which can be only 1.9 cm away; a small terminal branch of this artery can be as close as 1 cm away. As stated previously, one must also be aware of the femoral neurovascular bundle, which is located approximately 3.5 cm to 4 cm medially (see Table 2-2).

The final central compartment portal is the posterolateral portal. It is placed under direct arthroscopic visualization, and it is considered the easiest to establish because of a relative “soft spot” in the posterior soft-tissue envelope. The hip capsule is thinnest in this zone. The portal is placed on the same transverse line as the anterolateral portal but just posterior to the greater trochanter. It traverses the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus before entering the posterior capsule. The most obvious extra-articular structure at risk is the sciatic nerve, which is approximately 2.9 cm away (see Table 2-2). Fortunately, sciatic nerve injury is extremely rare. Most surgeons do not routinely make use of the posterolateral portal, because the majority of intra-articular pathology is localized to the anterolateral zones. Instead, the main purpose of this portal is to provide access for observation of the posterior aspect of the hip.

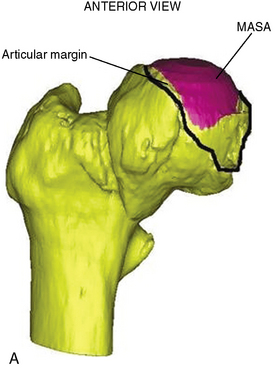

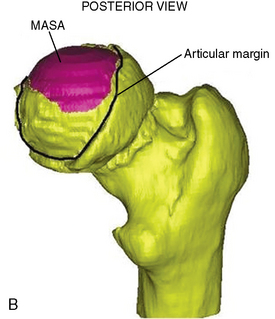

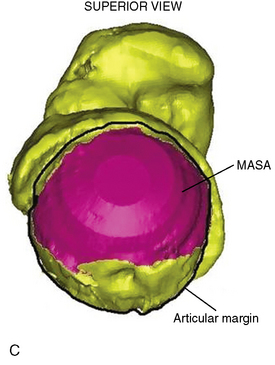

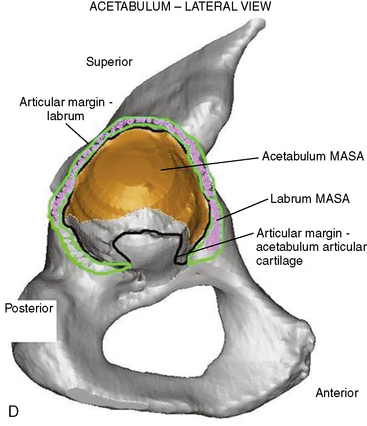

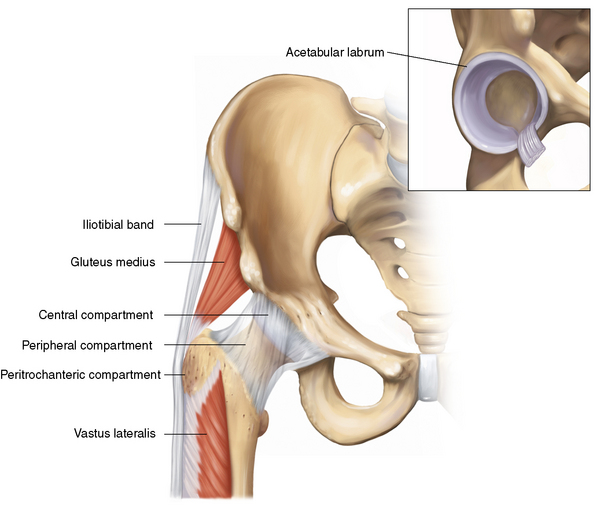

Examination of the hip through arthroscopic compartments

During the early days of hip arthroscopy, the most common indications were infection, loose body removal, and labral tears. Hip arthroscopy was confined to the central compartment, which included only the intra-articular region of the femoroacetabular joint. As the indications for hip arthroscopy have grown, the orthopedic surgeon must now routinely explore the areas of the joint outside of the central compartment. If surgery is confined to the central compartment, then overall mean accessible surface area is limited to 68% to 75% of the joint (Figure 2-8, A through D). However, by expanding arthroscopy to include the peripheral and peritrochanteric compartments, the surgeon can access more than 90% of the hip. Therefore, only the most posteromedial zones of the hip have limited accessibility. In addition, the indications for extra-articular procedures have recently expanded. Surgeons are now successfully navigating areas such as the iliopsoas bursa and the peritrochanteric space. Therefore, it is essential to appreciate the anatomic contents of the three hip compartments (Figure 2-9) and to familiarize oneself with the indications that are characteristic of each.

Central Compartment

The Capsule

The thickest part of this ligament lies anteriorly and coincides with the location of the majority of hip pathology that is amenable to arthroscopic intervention. Even after the portals are established, the capsule limits the maneuverability of the instrumentation and the arthroscope within the central compartment. Therefore, a limited capsulotomy is recommended to enhance mobility. This is usually accomplished with the assistance of a beaver blade or a radiofrequency device. If work is confined to the central compartment, it is sufficient to make mini-capsulotomy incisions in the areas in which the portals are penetrating the capsule. This allows the surgeon to access the femoroacetabular articular cartilage, the labrum, and the contents of the cotyloid fossa without significant challenge. However, if any substantial work is needed in the extra-articular areas (e.g., osteoplasty), then a horizontal or transverse capsular release in a “fish-mouth” or “T” pattern may be necessary, anteriorly or posteriorly (Figure 2-10, A and B). This allows for increased visualization and the ability to work in the peripheral compartment. Currently, the incision of the capsule, the extent of this incision, and the subsequent repair are performed at the discretion of the surgeon. Conversely, thermal capsular shrinkage can also be achieved by hip arthroscopy to stabilize the joint. Capsular plication in combination with shrinkage has also been shown to have good short-term results among patients with recurrent instability in the presence of an intact ligamentum teres.

The Labrum

The obturator artery, with contributions from the inferior and superior gluteal vessels, provides the blood supply to the labrum (Figure 2-11). Histologic studies have shown that the blood supply to the labrum is analogous to that of the knee menisci. The majority of the microvascular supply proliferates the capsulolabral junction with a relative paucity of vascularization to the innermost aspect of the labrum. Therefore, like the meniscus, the labrum may have the greatest healing potential at the peripheral capsulolabral junction.

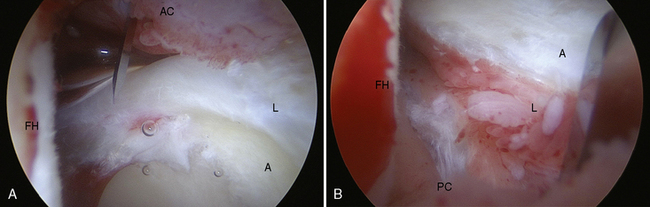

Peripheral Compartment

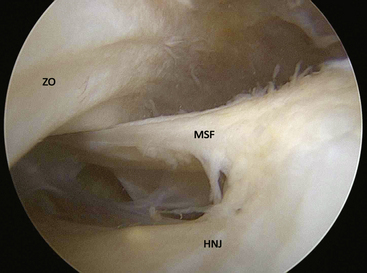

After entry into the peripheral compartment, the first anatomic landmark that can be readily identified is the medial synovial fold (Figure 2-12). The synovial folds are sheet-like collections of synovial tissue that run longitudinally in various parts of the peripheral compartment. The medial synovial fold is located at the anteromedial aspect of the femoral neck. The lateral synovial fold is located at the junction between the lateral and posterior femoral neck. It is important to closely inspect both of these structures, because their redundant tissue can easily obscure loose bodies. In addition, when significant synovitis is present, these synovial folds become inflamed and need to be thoroughly debrided as part of a synovectomy procedure.

Open approaches to the hip joint

Bardakos N.V., Villar R.N. The ligamentum teres of the adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2009;91(1):8-15.

Barrack R.L., Butler R.A. Avoidance and management of neurovascular injuries in total hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect.. 2003;52:267-274.

Byrd J.W. Avoiding the labrum in hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy.. 2000;16(7):770-773.

Byrd J.W. Labral lesions: an elusive source of hip pain case reports and literature review. Arthroscopy.. 1996;12(5):603-612.

Byrd J.W., Pappas J.N., Pedley M.J. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy.. 1995;11(4):418-423.

Clarke M.T., Arora A., Villar R.N. Hip arthroscopy: complications in 1054 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (406); 2003:84-88.

2008 Dandachli W., Kannan V., Richards R., Shah Z., Hall-Craggs M., Witt J. Analysis of cover of the femoral head in normal and dysplastic hips: new CT-based technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2008;90(11):1428-1434.

2003 Ferguson S.J., Bryant J.T., Ganz R., Ito K. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech.. 2003;36(2):171-178.

Ganz R., Gill T.J., Gautier E., Ganz K., Krugel N., Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2001;83:1119-1124.

2000 Gautier E., Ganz K., Krugel N., Gill T., Ganz R. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and its surgical implications. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2000;82(5):679-683.

2001 Glick J.M. Hip arthroscopy. The lateral approach. Clin Sports Med.. 2001;20(4):733-747.

Kagan A.2nd Rotator cuff tears of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (368); 1999:135-140.

Kelly B.T., Shapiro G.S., Digiovanni C.W., Buly R.L., Potter H.G., Hannafin J.A. Vascularity of the hip labrum: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy.. 2005;21(1):3-11.

Mason J.B., McCarthy J.C., O’Donnell J., et al Hip arthroscopy: surgical approach, positioning, and distraction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (406); 2003:29-37.

Murtha P.E., Hafez M.A., Jaramaz B., DiGioia A.M. 3rd. Variations in acetabular anatomy with reference to total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2008;90(3):308-313.

Philippon M.J. The role of arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy in the hip. Clin Sports Med.. 2001;20(4):817-829.

Rachbauer F., Kain M.S., Leuing M. The history of the anterior approach to the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):311-320.

Robertson W.J., Kelly B.T. The safe zone for hip arthroscopy: a cadaveric assessment of central, peripheral, and lateral compartment portal placement. Arthroscopy.. 2008;24(9):1019-1026.

Schmalzried T.P., Amstutz H.C., Dorey FJ. Nerve palsy associated with total hip replacement. Risk factors and prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 1991;73(7):1074-1080.

Strauss E.J., Campbell K., Bosco J.A. Analysis of the cross-sectional area of the adductor longus tendon: a descriptive anatomic study. Am J Sports Med.. 2007;35(6):996-999.

Vail T.P., Mariani E.M., Bourne M.H., Berger R.A., Meneghini R.M. Approaches in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 2009;91(Suppl 5):10-12.

Voos J.E., Ranawat A.S., Kelly B.T. The peritrochanteric space of the hip. Instr Course Lect.. 2009;58:193-201.