Chapter 660 Arthropod Bites and Infestations

660.1 Arthropod Bites

Clinical Manifestations

The type of reaction that occurs after an arthropod bite depends on the species of insect and the age group and reactivity of the human host. Arthropods may cause injury to a host by various mechanisms, including mechanical trauma, such as the lacerating bite of a tsetse fly; invasion of host tissues, as in myiasis; contact dermatitis, as seen with repeated exposure to cockroach antigens; granulomatous reaction to retained mouthparts; transmission of systemic disease; injection of irritant cytotoxic or pharmacologically active substances, such as hyaluronidase, proteases, peptidases, and phospholipases in sting venom; and induction of anaphylaxis. Most reactions to arthropod bites depend on antibody formation to antigenic substances in saliva or venom. The type of reaction is determined primarily by the degree of previous exposure to the same or a related species of arthropod. When someone is bitten for the first time, no reaction develops. An immediate petechial reaction is occasionally seen. After repeated bites, sensitivity develops, producing a pruritic papule (Fig. 660-1) approximately 24 hr after the bite. This is the most common reaction seen in young children. With prolonged, repeated exposure, a wheal develops within minutes after a bite, followed 24 hr later by papule formation; this combination of reactions is seen commonly in older children. By adolescence or adulthood, only a wheal may form, unaccompanied by the delayed papular reaction. Thus, adults in the same household as affected children may be unaffected. Ultimately, as a person becomes insensitive to the bite, no reaction occurs at all. This stage of nonreactivity is maintained only as long as the individual continues to be bitten regularly. Individuals in whom papular urticaria develops are in the transitional phase between development of primarily a delayed papular reaction and development of an immediate urticarial reaction.

Papular urticaria occurs principally in the first decade of life. It may occur at any time of the year. The most common culprits are species of fleas, mites, bedbugs, gnats, mosquitoes, chiggers, and animal lice. Individuals with papular urticaria have predominantly transitional lesions in various stages of evolution between delayed-onset papules and immediate-onset wheals. The most characteristic lesion is an edematous, red-brown papule (Fig. 660-2). An individual lesion frequently starts as a wheal that, in turn, is replaced by a papule. A given bite may incite an id reaction at distant sites of quiescent bites in the form of erythematous macules, papules, or urticarial plaques. After a season or two, the reaction progresses from a transitional to a primarily immediate hypersensitivity urticarial reaction.

660.2 Scabies

Clinical Manifestations

In an immunocompetent host, scabies is frequently heralded by intense pruritus, particularly at night. The first sign of the infestation often consists of 1- to 2-mm red papules, some of which are excoriated, crusted, or scaling. Threadlike burrows are the classic lesion of scabies (Fig. 660-3) but may not be seen in infants. In infants, bullae and pustules are relatively common. The eruption may also include wheals, papules, vesicles, and a superimposed eczematous dermatitis (Fig. 660-4). The palms, soles, and scalp are often affected. In older children and adolescents, the clinical pattern is similar to that in adults, in whom preferred sites are the interdigital spaces, wrist flexors, anterior axillary folds, ankles, buttocks, umbilicus and belt line, groin, genitals in men, and areolas in women. The head, neck, palms, and soles are generally spared. Red-brown nodules, most often located in covered areas such as the axillae, groin, and genitals, predominate in the less common variant called nodular scabies. Additional clues include facial sparing, affected family members, poor response to topical antibiotics, and transient response to topical steroids. Untreated, scabies may lead to eczematous dermatitis, impetigo, ecthyma, folliculitis, furunculosis, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and id reaction. Glomerulonephritis has developed in children from streptococcal impetiginization of scabies lesions. In some tropical areas, scabies is the predominant underlying cause of pyoderma. A latent period of about 1 mo follows an initial infestation. Thus, itching may be absent and lesions may be relatively inapparent in contacts who are asymptomatic carriers. On re-infestation, however, reactions to mite antigens are noted within hours.

Differential Diagnosis

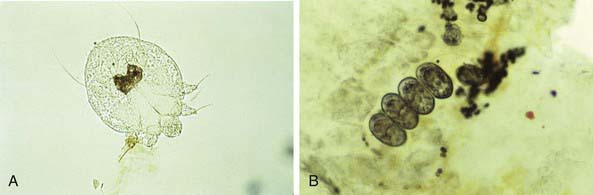

Differential diagnosis of scabies can often be made clinically but is confirmed by microscopic identification of mites (Fig. 660-5A), ova, and scybala (Fig. 660-5B) in epithelial debris. Scrapings most often test positive when obtained from burrows or fresh papules. A reliable method is application of a drop of mineral oil on the selected lesion, scraping of it with a No. 15 blade, and transferring the oil and scrapings to a glass slide.

Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

Guldbakke KK, Khachemoune A. Crusted scabies: a clinical review. J Drug Dermatol. 2006;5:221-227.

Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367:1767-1774.

Karthikeyan K. Scabies in children. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:ep65-ep69.

Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 3):S153-S159.

Strong M, Johnstone PW: Interventions for treating scabies, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (18):CD000320, 2007.

660.3 Pediculosis

Pediculosis capitis is an intensely pruritic infestation of lice in the scalp hair. Fomites and head-to-head contact are important modes of transmission. In summer months in many areas of the USA and in the tropics at all times of the year, shared combs, brushes, or towels have a more important role in louse transmission. Translucent 0.5-mm eggs are laid near the proximal portion of the hair shaft and become adherent to one side of the shaft (Fig. 660-6). A nit cannot be moved along or knocked off the hair shaft with the fingers. Secondary pyoderma, after trauma due to scratching, may result in matting together of the hair and cervical and occipital lymphadenopathy. Hair loss does not result from pediculosis but may accompany the secondary pyoderma. Head lice are a major cause of numerous pyodermas of the scalp, particularly in tropical environments. Lice are not always visible, but nits are detectable on the hairs, most commonly in the occipital region and above the ears, rarely on beard or pubic hair. Dermatitis may also be noted on the neck and pinnae. An id reaction, consisting of erythematous patches and plaques, may develop, particularly on the trunk. For unknown reasons, head lice rarely infest African Americans.

Pediculosis pubis is transmitted by skin-to-skin or sexual contact with an infested individual; the chance of acquiring the lice with one sexual exposure is 95%. The infestation is usually encountered in adolescents, although small children may occasionally acquire pubic lice on the eyelashes. Patients experience moderate to severe pruritus and may develop a secondary pyoderma from scratching. Excoriations tend to be shallower, and the incidence of secondary infection is lower than in pediculosis corporis. Maculae ceruleae are steel-gray spots, usually < 1 cm in diameter, which may appear in the pubic area and on the chest, abdomen, and thighs. Oval translucent nits, which are firmly attached to the hair shafts, may be visible to the naked eye or may be readily identified by a hand lens or by microscopic examination (see Fig. 660-6). Grittiness, as a result of adherent nits, may sometimes be detected when the fingers are run through infested hair. Adult lice are difficult to detect than head or body lice because of their lower level of activity and smaller, translucent bodies. Because pubic lice occasionally may wander or may be transferred to other sites on fomites, terminal hair on the trunk, thighs, axillary region, beard area, and eyelashes should be examined for nits. The coexistence of other venereal diseases should be considered. Treatment with a 10-min application of a pyrethrin preparation is usually effective. Re-treatment may be required in 7-10 days. The shampoo form of lindane, which requires a 10-min application time, is an alternative choice, but lindane cream and lotion are no longer recommended for treatment of pubic lice. Infestation of eyelashes is eradicated by petrolatum applied 3 to 5 times per 24 hr for 8-10 days. Clothing, towels, and bed linens may be contaminated with nit-bearing hairs and should be thoroughly laundered or dry-cleaned.

Ameen M, Arenas R, Villanueva-Reyes J, et al. Oral ivermectin for treatment of pediculosis capitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(11):991-993.

Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):896-904.

Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):717-724.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves head lice treatment for children and adults. (website) http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm240302.htm Accessed April 23, 2011

Frankowski BL, Bocchini JAJr. Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases: Clinical report: head lice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:392-403.

Jahnke C, Bauer E, Hengge UR, et al. Accuracy of diagnosis of pediculosis capitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:309-313.

Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:965-974.

Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 3):S153-S159.

The Medical Letter: Benzyl alcohol lotion for head lice. Med Lett. 2009;51(1317):57-59.

Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(1):19-24.

Nutanson I, Steen C, Schwartz RA. Pediculosis corporis: an ancient itch. Acta Dermatovenereol Croat. 2007;15:33-38.

Tebruegge M, Pantazidou A, Curtis N. What’s bugging you? An update on the treatment of head lice infestation. Arch Dis Child Pract Ed. 2011;96:2-8.