Chapter 674 Arthrogryposis

Definition

Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC) is a congenital anomaly in the newborn involving multiple curved joints (see Fig. 674-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com ![]() ). Arthrogryposis is a descriptive term and not an exact diagnosis, as there are as many as 300 possible underlying causes.

). Arthrogryposis is a descriptive term and not an exact diagnosis, as there are as many as 300 possible underlying causes.

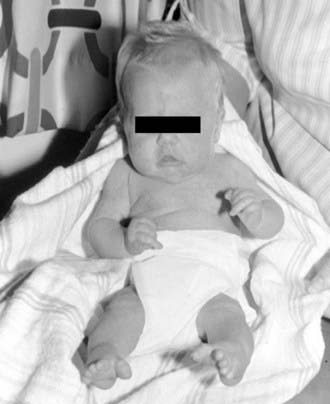

The incidence of classic AMC is approximately 1/3,000 live births, and the three main groups include classic AMC, in which the limbs are primarily involved and the muscles are deficient or absent (amyoplasia) (Fig. 674-2); arthrogryposis in association with major neurogenic (brain, spinal cord, anterior horn cell, or peripheral nerve) or myopathic (congenital muscular dystrophy, myopathy, toxic myopathy) dysfunction; and arthrogryposis in association with other major anomalies and specific syndromes such as diastrophic dysplasia and craniocarpotarsal dystrophy (Table 674-1).

Table 674-1 ASSOCIATED ETIOLOGIES OF ARTHROGRYPOSIS

ARTHROGRYPOSIS DUE TO NERVOUS SYSTEM DISORDERS

DISTAL ARTHROGRYPOSIS SYNDROMES

PTERYGIUM SYNDROMES

MYOPATHIES

ABNORMALITIES OF JOINTS AND CONTIGUOUS TISSUE

SKELETAL DISORDERS

INTRAUTERINE AND MATERNAL FACTORS

MISCELLANEOUS

SINGLE JOINT

Modified from Mennen U, Van Heest A, Ezaki MB: Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, J Hand Surg [Br] 30:468–474, 2005.

Clinical Features

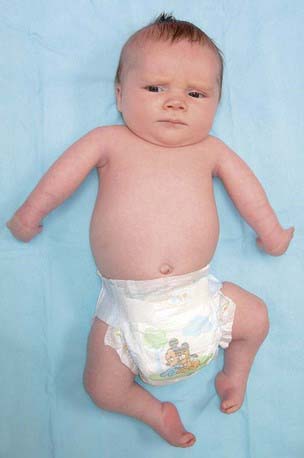

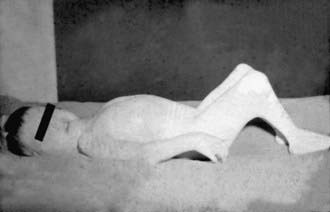

Multiple rigid joint deformities are present with defective muscles and normal sensation. There is rigidity of several joints in each case, resulting from both short tight muscles and capsular contractures. Pterygium may be present on the flexor aspects of contracted joints (Fig. 674-3). There is often an absence or fibrosis of muscles or muscle groups. There is normal intellectual development in most cases. All four limbs are involved in the classic form (AMC), but the condition can also occur in the upper or lower limbs. An autosomal dominant variant called distal arthrogryposis involves the hands and feet with severe deformation but with only minor contractures more proximally; scoliosis is a possible development. To date, 10 different distal arthrogryposes have been described. They are classified according to the proportion of features they share (Table 674-2). In addition to the multiple joint contractures, the lack of skin creases (cylindrical or tubular limbs) and deep dimples over the joints are very characteristic (Fig. 674-4). There is dislocation of joints, most commonly the hip but occasionally the knee; the trunk is rarely affected. Other congenital anomalies such as cryptorchidism, hernias, and gastroschisis can occur.

Figure 674-3 Fixed flexion of the knees in a boy with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita.

(From Hosalkar HS, Moroz L, Drummond DS, et al: Neuromuscular disorders of infancy and childhood and arthrogryposis. In Dormans J, editor: Pediatric orthopedics: core knowledge in orthopedics, Philadelphia, 2005, Mosby, pp 454–482.)

Table 674-2 CURRENT LABELS AND OMIM NUMBERS FOR THE DISTAL ARTHROGRYPOSIS SYNDROMES

| SYNDROME | NEW LABEL | OMIM NUMBER |

|---|---|---|

| Distal arthrogryposis type 1 | DA1 | 108120 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 2A (Freeman-Sheldon syndrome) | DA2A | 193700 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 2B (Sheldon-Hall syndrome) | DA2B | 601680 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 3 (Gordon syndrome) | DA3 | 114300 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 4 (scoliosis) | DA4 | 609128 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 5 (ophthalmoplegia, ptosis) | DA5 | 108145 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 6 (sensorineural hearing loss) | DA6 | 108200 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 7 (trismus-pseudocamptodactyly) | DA7 | 158300 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 8 (autosomal dominant multiple pterygium syndrome) | DA8 | 178110 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 9 (congenital contractural arachnodactyly) | DA9 | 121050 |

| Distal arthrogryposis type 10 (congenital plantar contractures) | DA10 | 187370 |

OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

From Bamshad M, Van Heest AE, Pleasure D: Arthrogryposis: a review and update, J Bone Joint Surg Am 91 Suppl 4:40–46, 2009.

Figure 674-4 Characteristic lack of skin creases and tubular limbs.

(From Hosalkar HS, Moroz L, Drummond DS, et al: Neuromuscular disorders of infancy and childhood and arthrogryposis. In Dormans J, editor: Pediatric orthopedics: core knowledge in orthopedics, Philadelphia, 2005, Mosby, pp 454–482.)

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is shown in Table 674-3.

Table 674-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CONGENITAL CONTRACTURES

NEUROGENIC

MYOPATHIC

CONNECTIVE TISSUE

MISCELLANEOUS

Principles of Orthopedic Management of Patients with Arthrogryposis and Multiple Congenital Contractures

Lower Limbs

Foot Involvement

An extensive posteromedial and posterolateral release is recommended. If the foot fails to correct with even the most extensive soft-tissue release or relapses quickly within 2-3 yr, talectomy may be considered. The Ilizarov technique and apparatus do offer an opportunity to correct these deformities by gradual distraction and neohistiogenesis (Fig. 674-5). Applications of this fixator in the pediatric foot have been fairly successful and satisfactory. In the case of older children with neglected or relapsed equinovarus deformity, correction can be best obtained by triple arthrodesis. In rare cases of recurrence of the deformity after triple arthrodesis (at the level of the ankle), a pantalar arthrodesis may be offered by an easy conversion of the triple arthrodesis.

Spine

In consistency with the principle that the severity of the stiffness and deformity increases toward the periphery of limbs and that the more central or proximal areas are less involved, a straight, supple, and well-balanced trunk is an important asset. Scoliosis occurs commonly in arthrogryposis because of a high incidence of congenital curves (Chapter 671).

Alves PV, Zhao L, Patel PK, et al. Arthrogryposis: diagnosis and therapeutic planning for patients seeking orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18(4):838-843.

Bamshad M, Van Heest AE, Pleasure D. Arthrogryposis: a review and update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 4):40-46.

Fixsen J. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. In: Benson MK, MF Macnicol MF, Parsch K, editors. Children’s orthopaedics and fractures. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:293-298.

Fassier A, Wicart P, Dubousset J, et al. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. Long-term follow-up from birth until skeletal maturity. J Child Orthop. 2009;3(5):383-390.

Hall JG. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita: etiology, genetics, classification, diagnostic approach, and general aspects. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;6:159-166.

Hosalkar HS, Moroz L, Drummond DS, et al. Neuromuscular disorders of infancy and childhood and arthrogryposis. In: Dormans J, editor. Pediatric orthopedics: core knowledge in orthopedics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005:454-482.

Mennen U, Van Heest A, Ezaki MB. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2005;30:468-474.

Navti OB, Kinning E, Vasudevan P, et al. Review of perinatal management of arthrogryposis at a large UK teaching hospital serving a multiethnic population. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30(1):49-56.