9 Arthritis and other joint disorders

ARTHRITIS

The term arthritis is used here to include both inflammatory and degenerative lesions of a joint.1 It implies a diffuse lesion affecting the joint as a whole. It does not include localised mechanical disorders such as loose body formation or tears of the menisci of the knee, which are better designated as internal derangements. Nor should it embrace acute injuries of joints.

Types of arthritis

For convenience the infective types of arthritis, specifically pyogenic and tuberculous arthritis, have been dealt with in Chapter 7 together with the bone infections caused by the same organisms. Although other types of arthritis, particularly rheumatoid arthritis, have a major inflammatory component they have not been shown to be associated with a specific infective organism or virus. They are therefore considered here together with degenerative osteoarthritis and the less common types of arthritis associated with metabolic disturbances such as gout.

The types of non-infective arthritis that are common, taken worldwide, are:

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (Rheumatoid polyarthritis)

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammation of joints, often associated with mild constitutional symptoms. It nearly always affects several joints at the same time (polyarthritis). Joint changes of a similar nature also occur in a number of other conditions such as juvenile chronic arthritis (Still’s disease), Reiter’s syndrome, psoriasis, lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue or collagen diseases.

Cause. The cause is unknown. At present only two possibilities attract serious consideration:

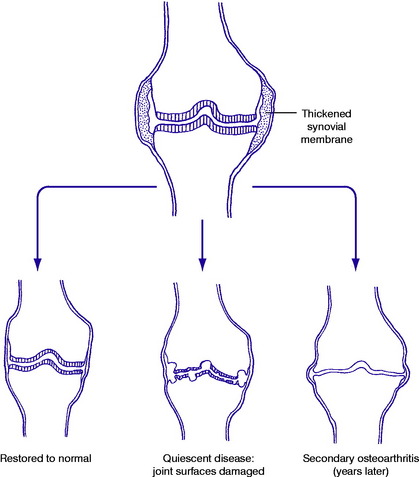

Pathology. The synovial membrane is thickened by chronic inflammatory changes: characteristically it is infiltrated with macrophage-like cells and T-cell lymphocytes (Fig. 9.1). Later the articular cartilage is gradually softened and eroded, and the subchondral bone may also be eroded, characteristically at the joint margins – probably from the action of lytic enzymes and inflammatory mediators produced in the thickened synovial membrane. The eroded surfaces become covered by a soft membrane of inflammatory tissue known as ‘pannus’.

On examination the affected joints are swollen from synovial thickening. The overlying skin is warmer than normal. The range of joint movements is restricted, and movement causes pain, especially at the extremes. These clinical features are often more severe in sero-positive disease than when rheumatoid factor is absent from the serum.

Extra-articular features may include enlargement of lymph nodes, muscle wasting, subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules, and anaemia.

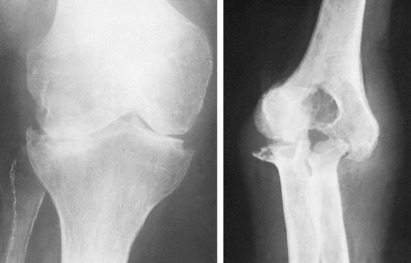

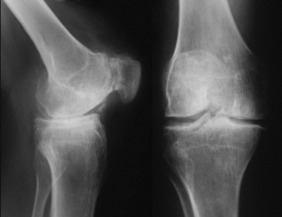

Imaging. Radiographic features: At first there is no alteration from the normal. Later, there is diffuse rarefaction in the area of the joint. Eventually destruction of joint cartilage may lead to narrowing of the cartilage space and, in severe cases, to localised erosion of the bone ends (Fig. 9.2) especially in periarticular sites. Radioisotope bone scanning shows increased uptake of the isotope in the region of affected joints.

A search should always be made for evidence of one of the distinct clinical entities that may be associated with joint changes of a rheumatoid type. The most important of such conditions are:

These conditions are all sero-negative, and they may be associated with ankylosing spondylitis.

Methods of treatment may be classified into the following categories:

Drugs. Drugs used in rheumatoid arthritis fall mainly into the categories of the NSAIDs, and the potent anti-inflammatory agents grouped under the heading of corticosteroids. A logical plan is to use aspirin since it has both analgesic and mild anti-inflammatory properties, but to be effective it may have to be given in fairly large doses. Alternative first-line drugs should probably be chosen from the group of NSAIDs, which includes indometacin, ibuprofen, naproxen, phenoprofen and piroxicam. Due regard must be paid to the risk of side effects: gastric pain is a common complaint with most of these drugs, and more serious complications, such as gastric bleeding, are seen occasionally.

In general, it is wise to avoid repeated injections.

Operation. Operation has an important place in treatment, but each operation must be considered as a component in the overall plan of management and not as a substitute for other measures. Operation may be applicable to the early stages of the disease, or it may be used in the later stages to salvage a joint that has been permanently damaged and remains a source of persistent pain.

Further details are given in the sections on individual joints.

JUVENILE CHRONIC ARTHRITIS (Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; Still’s disease)

These subgroups vary in age of onset, sex incidence, course, complications, and prognosis.

The sero-negative disease with sacro-iliitis is commoner in boys than in girls and tends not to begin until late in childhood: it may lead on to ankylosing spondylitis in early adult life. Most such patients show a positive test for HLA-B27 antigen and there is often clinical overlap between these patients and relatives with ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. It is thus probable that there is a hereditary factor in the causation.

OSTEOARTHRITIS (Degenerative arthritis; arthrosis; osteoarthrosis; hypertrophic arthritis; post-traumatic arthritis)

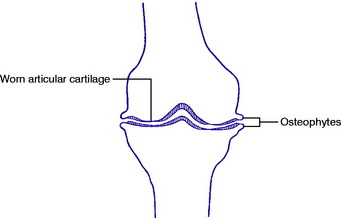

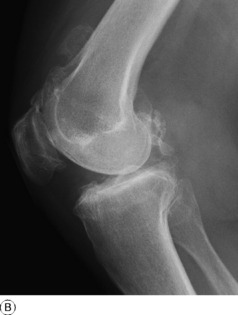

Pathology. Any joint may be affected, the lower limb joints more often than the upper. The articular cartilage is slowly worn away until eventually the underlying bone is exposed (Fig. 9.3). This subchondral bone becomes hard and glossy (‘eburnation’), though it may also show the presence of degenerative cysts. Meanwhile the bone at the margins of the joint hypertrophies to form a rim of projecting spurs known as osteophytes. There is no primary change in the capsule or synovial membrane, but the recurrent strains to which an osteoarthritic joint is subject often lead to slight thickening and fibrosis.

Clinical features. Most patients with osteoarthritis are past middle age. When it occurs in younger patients there is usually a clear predisposing cause such as previous injury or disease of the joint. The onset is very gradual, with pain that increases almost imperceptibly over months and years. Movements slowly become more and more restricted. In some joints (notably the hip) deformity is a common feature in the later stages. This means that the joint cannot be placed in the neutral (anatomical) position.

Radiographic features. The characteristic features of osteoarthritis are:

Treatment. The management of osteoarthritis exemplifies well the three categories of treatment that should be considered in every orthopaedic problem – namely:

When severe disability, particularly rest or night pain and limitation of function, is unrelieved by conservative treatment, operation may be justified. Among the operations available are osteotomy to realign a joint; arthroplasty (the construction of a new joint) (p. 40); and arthrodesis (elimination of the joint by fusion) (p. 39). Osteotomy is useful mainly at the knee to correct varus or valgus deformity, and is occasionally used at the hip, but will only provide pain relief for a period of a few years. Arthroplasty has become the operation of choice in the majority of patients particularly when osteoarthritis affects the hip and knee, where it can provide good painless function in 95% of patients after 10–15 years. For a few joints, particularly in the hands and feet, arthrodesis may still be the operation of choice. Further details of treatment will be given in the sections on individual joints.

GOUTY ARTHRITIS (Podagra; urate crystal synovitis)

Other manifestations. Deposits of uric acid salts (tophi) are common in the ear cartilages, where they form palpable nodules. Similar tophi may also occur at other sites.

Radiographic features. In acute attacks of articular gout the joints do not show any radiographic change. In chronic gout the deposits of uric acid salts in the bone ends show as clear-cut erosions adjacent to the articular surfaces, for the deposits are transradiant (Fig. 9.5).

Chronic gout involving several joints may simulate rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment. For acute attacks reliance is usually placed upon a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as indometacin or naproxen. Colchicine is also effective. The affected joint should be rested until the attack has subsided. A large effusion in a major joint such as the knee should be aspirated and replaced by an instillation of hydrocortisone.

PYROPHOSPHATE ARTHROPATHY (Pseudogout)

With the general acceptance of the idea that joint manifestations in gout are caused by the presence of urate crystals, it has more recently come to be appreciated that similar manifestations may be induced by the crystals of other salts. In most such cases the crystals are composed of calcium pyrophosphate showing positive birefringence, and characteristically calcification of articular cartilage or of menisci is demonstrable radiologically (Fig. 9.6). Arthritis of this type has been termed ‘pseudogout’. It usually presents as a chronic arthritis with characteristic calcification of cartilage, but it may occur in an acute form mimicking a joint infection, from the shedding of crystals into the synovial fluid. The diagnosis can be confirmed by the finding of pyrophosphate crystals in the aspirated joint fluid. Treatment of an acute attack should be by rest, aspiration of joint fluid with intra-articular steroid injection, and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent.

HAEMOPHILIC ARTHRITIS

Pathology. The term ‘haemophilia’ is used loosely to embrace a group of different defects in the process of coagulation of the blood. Classical haemophilia, the commonest of the group, occurs in males but is transmitted by females. There is an inherited deficiency of a specific clotting factor known as antihaemophilic factor (Factor VIII). In consequence the clotting time of the blood is prolonged and there is a tendency to undue bleeding, external or internal, when even quite small vessels are cut or torn. Joint manifestations are caused by haemorrhage into a joint, occurring after a minor strain or even without any known injury. The joints most commonly affected are those most vulnerable to strain – especially the knee, elbow, and ankle. The joint cavity is distended with blood (haemarthrosis), which is later slowly reabsorbed if the joint is rested. Recurrent haemarthroses lead eventually to degenerative changes in the articular cartilage and to fibrosis of the synovial membrane.

Imaging. In the later stages of the disease, particularly in those patients who have multiple bleeds from poor control of their clotting factor, the joints may show extensive surface erosions, juxta-articular bone cysts, with bone destruction and deformities (Fig. 9.7).

Failing adequate supplies of antihaemophilic factor, resort must be had to prolonged splintage.

The future outlook for haemophilic patients is much improved by the new-found ability to manufacture Factor VIII in commercial quantities by genetic engineering technology. If such a product can be developed to the point of being effective when taken by mouth the advantage will clearly be even greater.

NEUROPATHIC ARTHRITIS (Charcot’s osteoarthropathy)

Clinical and radiographic features. The patient is usually in adult life. The main symptoms are swelling and instability of the affected joint. Since the joint is insensitive pain is slight or, sometimes, absent. On examination the joint is thickened, mostly from irregular hypertrophy of the bone ends. The range of movement is moderately restricted, and there is marked lateral laxity leading to instability. In extreme cases the joint may be dislocated. Further examination will reveal evidence of the underlying neurological disorder. Radiographs show severe disorganisation of the joint (Fig. 9.8). The changes are basically those of osteoarthritis, but enormously exaggerated. There is a loss of cartilage space and some absorption of the bone ends, often with considerable hypertrophy of bone at the joint margins.

ARTHRITIS OF RHEUMATIC FEVER

Clinical features. The patient is usually a child over 10, or a young adult. There is constitutional illness, with malaise and pyrexia. A joint becomes painful and swollen, and soon afterwards other joints are likewise affected. On examination an affected joint is swollen, partly from contained fluid and partly from synovial thickening. The overlying skin is warmer than normal. Movements are markedly restricted, and painful if forced. Other features of rheumatic fever, such as carditis and chorea, should be looked for. Radiographs of affected joints do not show any alteration from the normal.

Investigations. There is a mild leucocytosis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased.

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS (Spondylitis ankylopoietica; Marie–Strümpell arthritis)

As the name implies, ankylosing spondylitis is primarily a disease of the spine, though in a few cases the arthritic changes involve also the proximal joints of the limbs, especially the hips. Briefly, it is a chronic inflammatory affection of the joints and ligaments of the spine, beginning in the sacro-iliac joints. It progresses slowly, the changes gradually creeping up the spinal column from below. The natural outcome is bony ankylosis of the affected joints (Fig. 9.9) but the disease may be arrested at any stage short of this.

Typically, ankylosing spondylitis affects men in early adult life, with a strong hereditary link to the HLA-B27 gene. After remaining active for several years it tends eventually to become quiescent, always leaving some degree of permanent stiffness of the spine. A fuller description is given in Chapter 13 (p. 229).

DISLOCATION AND SUBLUXATION OF JOINTS

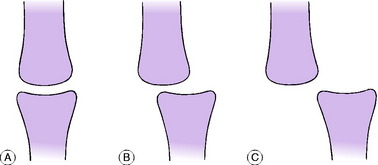

The cause of dislocation or subluxation of a joint may be congenital, spontaneous, traumatic, or recurrent. By definition, a joint is subluxated when its surfaces are partly displaced but retain some contact one with the other (Fig. 9.10B). A joint is dislocated or luxated when its articular surfaces are wholly displaced one from the other, so that all apposition between them is lost (Fig. 9.10C).

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION OR SUBLUXATION

The most important representative of this group is congenital (developmental) dislocation of the hip (p. 343). Congenital club foot (talipes equino-varus) (p. 434) may be regarded as congenital subluxation of the talo-navicular joint. Congenital displacement of other joints is rare: an example that is seen occasionally is congenital dislocation of the head of the radius.

SPONTANEOUS (PATHOLOGICAL) DISLOCATION OR SUBLUXATION

Displacement may occur spontaneously at any joint in consequence of a structural defect or of destructive disease. It is encountered frequently in the spine, where the stability of the intervertebral joints may be impaired by structural defects, by previous injury, or by destructive arthritis (pyogenic, rheumatoid, or tuberculous). In the foot, it is common for a phalanx to become dislocated dorsally at the metatarso-phalangeal joint in cases of severe clawing of the toes; and in the hands interphalangeal subluxation may occur in rheumatoid arthritis. Another example is the dislocation of the hip that sometimes complicates severe tuberculous arthritis or pyogenic arthritis. Spontaneous subluxation or dislocation is also a common feature of neuropathic arthritis (p. 147).

RECURRENT DISLOCATION OR SUBLUXATION

Certain joints are liable to repeated dislocation or subluxation. Usually, but not always, there has been an initial violent dislocation which causes permanent damage to the ligaments or articular surfaces. The joints most often affected are the shoulder (p. 263), the patello-femoral joint (p. 409), and the ankle (p. 433).

INTERNAL DERANGEMENTS OF JOINTS

The term internal derangement implies a localised mechanical fault which interferes with the smooth action of a joint. An internal derangement is distinct from arthritis, which is nearly always a diffuse lesion involving the joint as a whole (see p. 133).

Internal derangements will be considered in three groups:

INTERPOSITION OF SOFT TISSUE IN JOINTS

The smooth action of a joint may be obstructed by a displaced mass of soft tissue within it. The soft tissue most often responsible is an intra-articular fibrocartilage, especially a meniscus in the knee (p. 399). As a rule a fibrocartilage can be displaced only when it is torn. Other soft tissues that are occasionally interposed are synovial fringes and ligamentous tags.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS

Osteochondritis dissecans is a localised disorder of convex joint surfaces in which a segment of subchondral bone becomes avascular and, with the articular cartilage that covers it, may slowly separate from the surrounding bone to form a loose body.

Common sites. The only joints commonly affected are the knee and the elbow. In the knee the site of the lesion is nearly always the medial femoral condyle, and in the elbow, the capitulum of the humerus. Rarely the hip joint (femoral head) and the ankle joint (talus) are affected. The disorder of a metatarsal head known as Freiberg’s disease (p. 462) is thought by some to be an example of osteochondritis dissecans and by others to represent osteochondritis juvenilis. It shows some features common to both conditions.

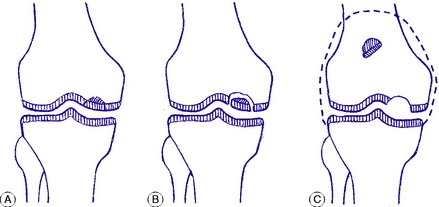

Pathology. A segment of the articular surface of a bone becomes avascular (Fig. 9.12A), and a line of demarcation slowly forms between the avascular segment and the surrounding normal bone (Fig. 9.12B). The affected segment varies in size: in the knee it often measures about one to three centimetres in diameter and half a centimetre in depth. It is always on the convex joint surface. If the segment is small it is sometimes re-attached spontaneously, especially in adolescents; but in most cases it finally separates to form a loose body in the joint, still covered by its articular cartilage (Fig. 9.12C). The resulting cavity in the articular surface of the bone fills with fibrous tissue, but there is inevitably some irregularity of the joint surface which predisposes to the later development of osteoarthritis.

Clinical features. The patient is an adolescent or a young adult. The early symptoms and signs are those of a mild mechanical irritation of the joint – namely a tendency to aching after use, with recurrent effusion of clear fluid. After separation of a fragment from the articular surface the clinical features are those of an intra-articular loose body: recurrent sudden locking of the joint accompanied by sharp pain and followed by effusion.

Treatment. Until a loose body has separated or appears ‘ripe’ for separation, treatment should be expectant. In the case of a small lesion in early adolescence rest in plaster for two months may allow spontaneous re-attachment of the fragment. When a fragment has separated it should usually be removed, though in the case of a large fragment it may be practicable to fix it back in position with a pin. Further details will be found in the appropriate sections on the knee (p. 405), the elbow (p. 286), and the foot (p. 445).