CHAPTER 74 Arterial Anatomy of the Upper Extremities

NORMAL ANATOMY OF THE SUBCLAVIAN ARTERY

General Anatomic Descriptions

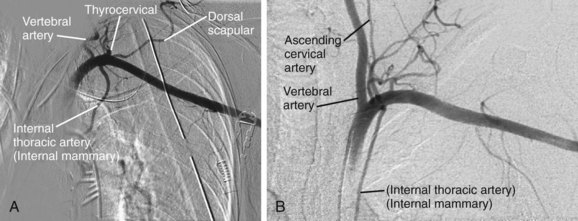

The subclavian artery arises from the brachiocephalic trunk (innominate artery) on the right and from the aorta on the left. It runs within the thoracic cage to the first rib, where it becomes superficial to the bony thorax and becomes the axillary artery. It gives rise to the vertebral artery, the internal thoracic artery (internal mammary artery), and the thyrocervical and costocervical trunks. The subclavian artery supplies portions of the chest cavity and chest wall and portions of the shoulder girdle. Ascending branches off the subclavian artery supply portions of the anterior neck, spinal cord, and brain (Fig. 74-1).

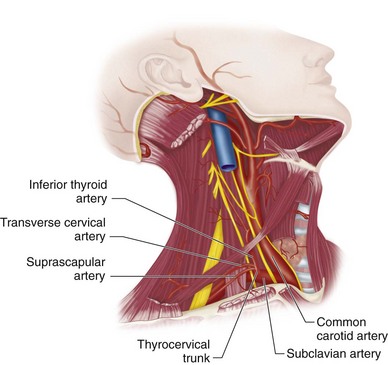

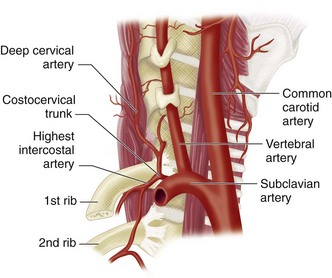

The vertebral artery is the first branch of the subclavian artery. The thyrocervical trunk and internal thoracic artery arise opposite each other from the anterosuperior and anteroinferior aspect of the subclavian artery. The thyrocervical trunk divides into the inferior thyroid artery with its characteristic looping course, the transverse cervical artery and the suprascapular artery (Fig. 74-2). It supplies the anterior neck, including the thyroid gland and the superior portion of the esophagus, as well as portions of the shoulder. The internal thoracic artery travels slightly anterior and inferiorly, deep to the thorax, to supply the rib cage and portions of the mediastinum. Inferiorly, it continues as the superior epigastric artery and anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery in the anterior abdominal wall. The costocervical trunk arises distal to the thyrocervical trunk from the posterosuperior aspect of the subclavian artery. It divides into the deep cervical artery and supreme intercostal artery (highest intercostal artery) to supply the first two or three intercostal spaces and the deep structures of the neck (Fig. 74-3).

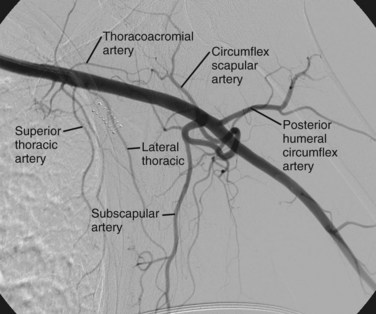

The first part of the axillary artery, from the first rib to the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle, gives rise to the superior thoracic artery, also called the highest thoracic artery. It supplies the chest wall (Fig. 74-4).

The second part of the axillary artery, posterior to the pectoralis minor muscle, gives rise to the thoracoacromial artery and lateral thoracic artery, which supply the shoulder, anterior axilla, and chest wall (see Fig. 74-4). The thoracoacromial artery pierces the overlying costocoracoid membrane anteriorly, dividing into pectoral, acromial, clavicular and deltoid branches. The lateral thoracic artery courses inferiorly to anastomose with the internal thoracic, subscapular, and intercostal arteries, along with pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial artery. It supplies lateral mammary branches in women and is also called the external mammary artery.

The third part of the axillary artery extends laterally from the outer border of the pectoralis minor muscle to the lower border of the teres major muscle and gives rise to three branches, the subscapular artery and the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries, which supply the posterior and lateral axilla (see Fig. 74-4). The subscapular artery divides into the circumflex scapular artery, the infrascapular artery (largest branch), and the dorsal thoracic artery. These branches anastomose with the lateral thoracic artery, intercostal arteries, and the deep branch of the transverse cervical artery. The anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries pass around the surgical neck of the humerus. The posterior circumflex humeral artery is the larger of the two.

Detailed Description of Specific Areas

Differential Considerations

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

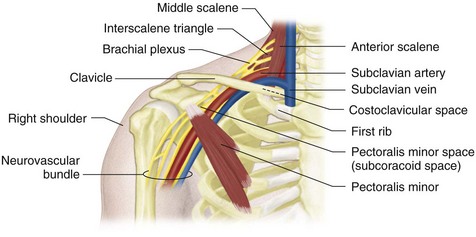

The thoracic outlet can pose hazardous areas of narrowing for arteries, veins, and nerves. The subclavian and axillary arteries are subject to compression at several narrow spaces along their course out of the thorax. The most common sites are the interscalene triangle, costoclavicular space, and subcoracoid space (Fig. 74-5). Compression of the neurovascular bundle is the most common form of thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) causing neurologic symptoms. However, the arterial type, seen in 1% to 2% of cases, is associated with the most serious complication of limb ischemia, which can result in limb loss. This chronic arterial compression is generally made worse with certain arm positions leading to intimal and medial wall injury. Over time, repetitive vessel trauma and flow disturbances promote poststenotic dilation, aneurysm formation, premature atherosclerosis, and/or embolization of platelet-fibrin deposits or thrombus from the diseased wall, leading to complete vessel occlusion. Both duplex ultrasound and CT angiography are used to detect vessel abnormalities in patients with suspected TOS. However, Longley and colleagues1 have observed an incidence of asymptomatic compression of the subclavian artery on Doppler ultrasound as high as 20% in normal volunteers.

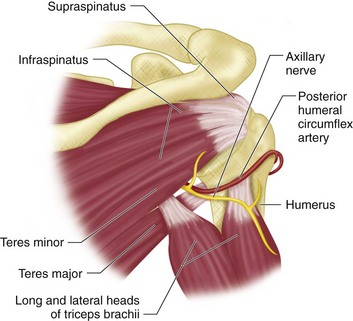

Quadrilateral Space Syndrome

The quadrilateral space is bounded by the humerus, teres major and teres minor muscles, and long head of the triceps muscle (Fig. 74-6). Because the posterior circumflex humeral artery and axillary nerve run through the quadrilateral space, compression of these structures by surrounding fibrous bands can lead to this syndrome. It is most evident in the abducted and externally rotated position. The phenomenon appears to be caused by compression of the axillary nerve rather than arterial compression. Mochizuki and associates2 have observed occlusion of the posterior circumflex humeral artery in 5 of 6 (80%) of asymptomatic volunteers, suggesting that demonstration of arterial compression is not helpful in establishing the diagnosis.

NORMAL ANATOMY OF THE BRACHIAL ARTERY

General Anatomic Descriptions

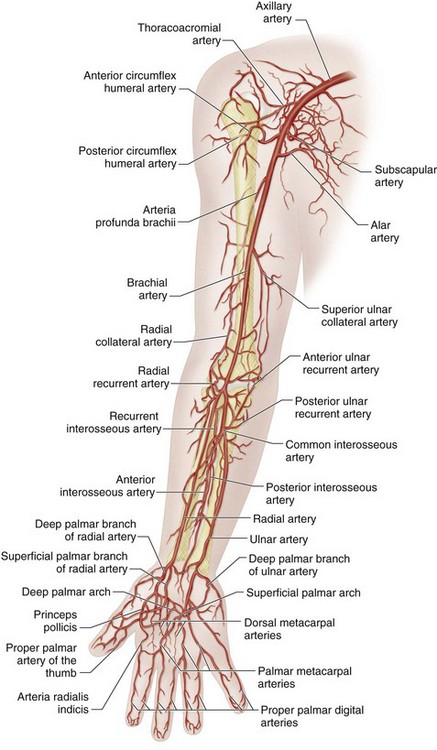

The brachial artery is the continuation of the axillary artery from the lower border of the teres major muscle to the level of the radial neck. The artery takes a medial course along the humerus, partially overlapped by the biceps and coracobrachialis muscles. It then takes a gradual turn anteriorly to the antecubital fossa, where it lies between the biceps tendon laterally and the median nerve medially. Here the vessel divides into the radial and ulnar arteries (Fig. 74-7). The brachial artery serves as a potential arterial access site because of its course along the humerus, which allows compressive hemostasis against the underlying bone.

FIGURE 74-7 Schematic drawing of the brachial artery and branches.

FIGURE 74-7 Schematic drawing of the brachial artery and branches.

(Adapted from Uflacker R. Atlas of Vascular Anatomy: An Angiographic Approach, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

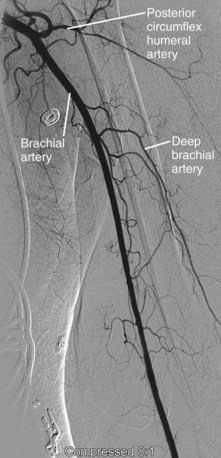

The brachial artery has multiple branches to include smaller muscular and nutrient vessels. However, the main branch arteries are the deep brachial and superior ulnar collateral arteries (Fig. 74-8). The deep brachial artery arises proximally and crosses posterior to the humerus, along with the radial nerve. It then divides into smaller collateral branches along the radial border of the humerus. The deep brachial artery first gives off the deltoid artery, which courses superiorly to collateralize with branches of the posterior humeral circumflex artery. The next branch is the middle collateral artery, which courses distally to anastamose with the interosseous recurrent artery and the rich collaterals about the elbow (see Fig. 74-7). The deep brachial artery then continues as the radial collateral artery to anastomose with the radial recurrent artery and the rich collaterals about the elbow, acting as an important alternative pathway when the brachial artery is occluded at the elbow.

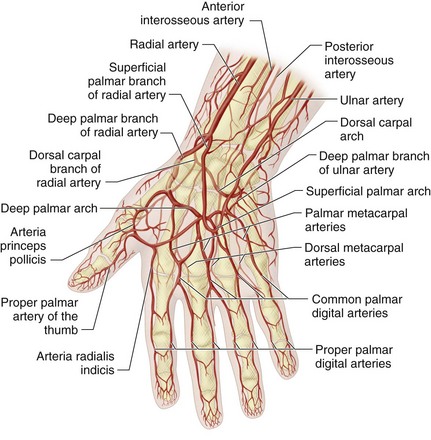

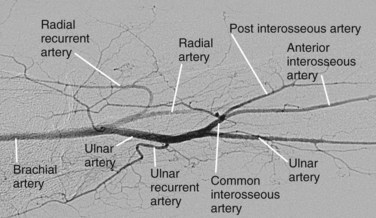

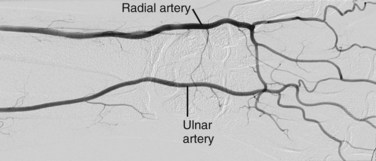

At the elbow, the brachial artery divides into the radial and ulnar arteries (Fig. 74-9). The radial artery begins in the antecubital fossa about 1 cm below the elbow joint. Although it is smaller than the ulnar artery, it is a more direct continuation of the brachial artery. The radial artery follows the course of the radius toward the lateral wrist, crosses the floor of the anatomic snuffbox formed by the scaphoid and trapezium, and ends by completing the deep palmer arch as it anastomoses with the deep palmer branch of the ulnar artery (Fig. 74-10).

FIGURE 74-10 Schematic drawing of the hand.

FIGURE 74-10 Schematic drawing of the hand.

(Adapted from Uflacker R. Atlas of Vascular Anatomy: An Angiographic Approach, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

The branches of the radial artery include the radial recurrent artery, muscular perforators, the deep palmar branch of the radial artery, and the superficial palmar branch of the radial artery. In the proximal forearm, the radial recurrent artery (see Fig. 74-9) ascends to anastomose eventually with the terminal portion of the deep brachial artery (radial collateral artery), thus serving as an important collateral in the elbow region. In the distal forearm and wrist, the deep palmar branch of the radial artery arises near the lower border of the pronator quadratus muscle and runs across the palmar aspect of the carpal bones. It anastomoses with the deep branch of the ulnar artery. The superficial palmar branch artery arises from the radial artery just proximal to the wrist, coursing forward through the thenar eminence. It normally anastomoses with the terminal portion of the ulnar artery to form the superficial palmar arterial arch (see Fig. 74-10).

The branches of the ulnar artery include the ulnar recurrent artery, posterior ulnar recurrent artery and common interosseous artery (see Fig. 74-9). The anterior ulnar recurrent artery is an important collateral around the medial aspect of the elbow. This vessel arises immediately inferior to the elbow and ascends to anastomose with the superior and inferior ulnar collateral arteries. The posterior ulnar recurrent artery is also an important collateral around the medial aspect of the elbow. This vessel arises somewhat more distally than the anterior ulnar recurrent artery, ascending posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus to anastomose with the superior and inferior ulnar collateral and interosseous recurrent arteries. The common interosseous artery arises immediately inferior to the radial tuberosity and quickly divides into the anterior and posterior interosseous arteries (see Fig. 74-9). The anterior interosseous artery descends along the volar surface of the interosseous membrane in the forearm, giving off muscular branches and the nutrient arteries of the radius and ulna. At the superior border of the pronator quadratus muscle, the anterior interosseous artery pierces the interosseous membrane to reach the dorsum of the forearm and anastomose with the posterior interosseous artery. The posterior interosseous artery descends along the dorsal surface of the interosseous membrane where, at the distal part of the forearm, it anastomoses with the termination of the anterior interosseous artery and with the dorsal carpal network. From the proximal aspect of the posterior interosseous artery, there is a branch (the posterior interosseous recurrent collateral) that ascends to the interval between the lateral epicondyle and olecranon to anastomose with the radial collateral branch of the deep brachial artery, posterior ulnar recurrent artery and inferior ulnar collateral artery.

NORMAL ANATOMY OF THE RADIAL AND ULNAR ARTERIES

General Anatomic Descriptions

Both the radial and ulnar arteries supply blood to the hand. The radial artery leaves the forearm by coursing dorsally to enter the anatomic snuffbox, deep to the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, and brevis muscles to the proximal space between the metacarpal bones of the thumb and index finger. Finally, it passes forward between the two heads of the first interosseous dorsalis muscles, into the palm of the hand, where it crosses the metacarpal bones. At the ulnar side of the hand, it unites with the deep palmar branch of the ulnar artery to form the deep palmar arch (see Fig. 74-10).

Detailed Description of Specific Areas

Normal Variants

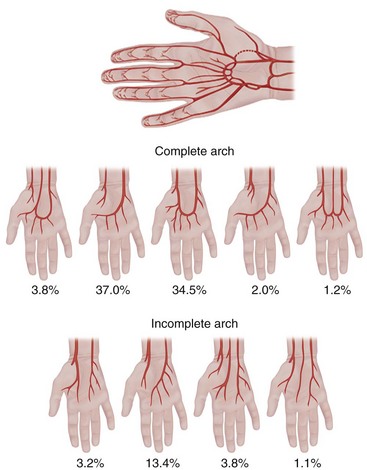

There are numerous variants of the palmar arches and digital arteries (Fig. 74-11). The superficial palmar arch may be complete (42%) or incomplete (58%) (Fig. 74-12). If the superficial palmar arch is prominent, the deep palmar arch will be small, and vice versa. Both palmar arches supply the fingers in only 40% of limbs.

FIGURE 74-11 Schematic drawing of the hand, with arch variations.

FIGURE 74-11 Schematic drawing of the hand, with arch variations.

(Adapted from Uflacker R. Atlas of Vascular Anatomy: An Angiographic Approach, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

Kadir S. Atlas of Normal and Variant Angiographic Anatomy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991.

Lippert H, Pabst R. Arterial Variations in Man. Classification and Frequency. Munich: JF Bergmann Verlag; 1985.

Uflacker R. Atlas of Vascular Anatomy: An Angiographic Approach, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

1 Longley D, Yedlicka J, Molina E, et al. Thoracic outlet syndrome: evaluation of the subclavian vessels by color duplex sonography. AJR Am Roentgenol. 1992;158:623-630.

2 Mochizuki T, Isoda H, Masui T, et al. Occlusion of the posterior humeral circumflex artery: detection with MR angiography in healthy volunteers and in a patient with quadrilateral space syndrome. AJR. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:625-627.

FIGURE 74-1

FIGURE 74-1

FIGURE 74-2

FIGURE 74-2

FIGURE 74-3

FIGURE 74-3

FIGURE 74-4

FIGURE 74-4

FIGURE 74-5

FIGURE 74-5

FIGURE 74-6

FIGURE 74-6

FIGURE 74-8

FIGURE 74-8

FIGURE 74-9

FIGURE 74-9

FIGURE 74-12

FIGURE 74-12