CHAPTER 72 Arterial Anatomy of the Abdomen

NORMAL ANATOMY

General Anatomic Descriptions

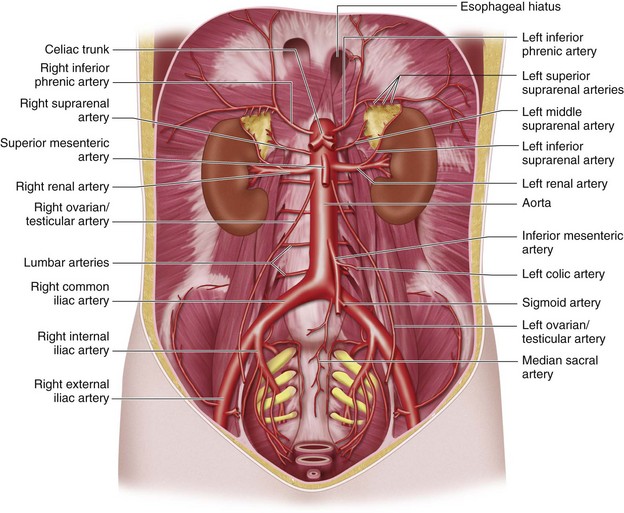

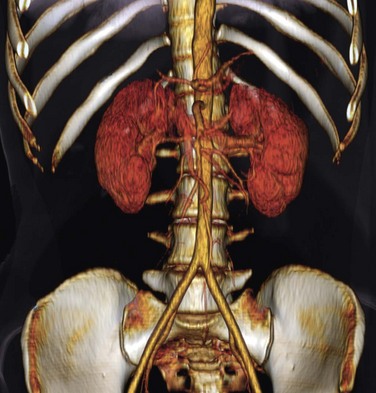

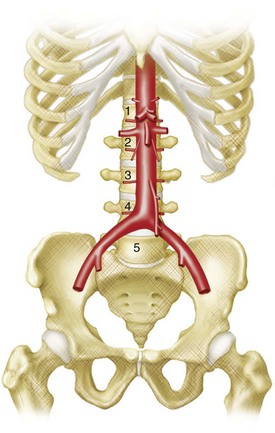

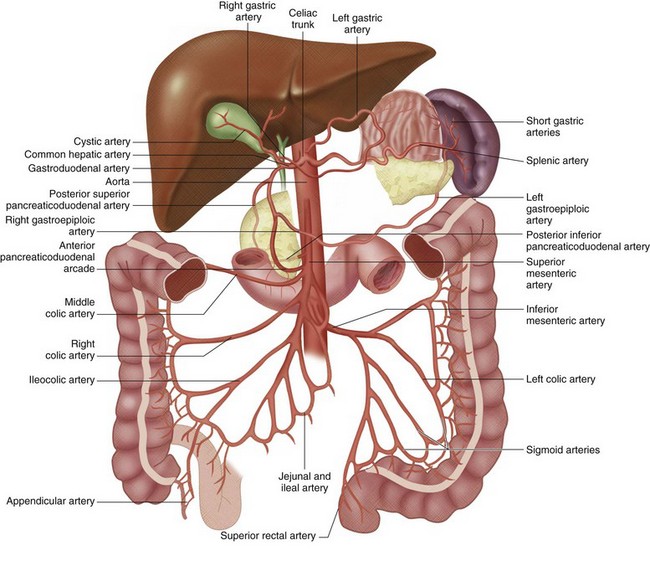

The abdominal aorta and its branches are responsible for the arterial blood supply to the abdominal organs (Figs. 72-1 and 72-2). From the thoracic cavity, the aorta courses through the diaphragm slightly to the left of midline at the aortic hiatus, most commonly anterior to the twelfth thoracic vertebral body.1 The normal aorta measures 1.5 to 2 cm in diameter and diminishes in caliber until its terminal bifurcation, typically at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebral body. During the process of vasculogenesis, embryonic folding during the fourth week parallels fusion of the paired dorsal aortae into a single median dorsal aorta in the abdomen.2 Major branches from the dorsal abdominal aorta subsequently develop ventrally, laterally, and posterolaterally and may be divided into four groups (Table 72-1).

| Group | Arterial Branches |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | |

Group 1 includes branches formed by the union of vitelline arteries arising from the wall of the yolk sac that supply organs depending on their location in the primitive gut.2 The developing gastrointestinal tract, or primitive gut, is often divided into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The foregut gives rise to the esophagus, stomach, proximal half of the duodenum, liver, and pancreas. The midgut gives rise to the distal half of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and the right two thirds of the transverse colon. The hindgut gives rise to the left two thirds of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. From the dorsal aorta, the three dominant vitelline arteries are further refined into the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and inferior mesenteric artery, which correspond to the three primitive gut regions, respectively.

Group 2 (renal and adrenal branches) includes branches supplying the kidneys and adrenal glands.

The arterial supply of the pelvic organs and pelvic wall courses through the internal iliac arteries, which originate at the bifurcation of the common iliac artery at the sacroiliac junction. Arterial anatomy of the pelvis is presented in Chapter 73.

Detailed Description of Specific Areas

Normal Variants

Group 1: Celiac Trunk and Mesenteric Arteries

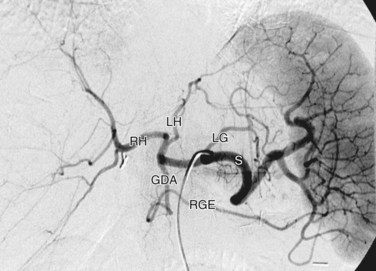

The celiac trunk is a short (1 to 2 cm) ventral branch of the abdominal aorta arising below the aortic hiatus, typically between T12 and L1 (Fig. 72-3).1,3,4 The foregut organs are supplied by the celiac trunk’s trifurcated branches, the left gastric, common hepatic, and splenic arteries, in up to 75% of individuals (Fig. 72-4). Rarely, a common origin of the celiac and superior mesenteric artery develops; however, most variants involve separate origins of one or more of the three main celiac branches. The left gastric artery is ordinarily the first and smallest celiac branch, supplying the distal esophagus and stomach. Coursing along the lesser curvature of the stomach, the left gastric branches unite with the right gastric branches, forming a vascular arcade. Further anastomoses exist between the left gastric artery and the short gastric arteries from the splenic artery as well as the left gastroepiploic (sometimes called gastro-omental) artery.

Rounding out the branches of the celiac trunk is the common hepatic artery, an intermediate-sized branch that gives rise to the gastroduodenal artery, right gastric artery and proper hepatic artery. The branching pattern of the proper hepatic artery is frequently variable. Conventionally, the artery divides at the porta hepatis into the right and left hepatic arteries (Fig. 72-5). The described branching pattern of the common hepatic artery into right and left hepatic arteries at the portohepatic artery is seen in only 36% to 50% of patients, according to multiple cadaveric and angiographic studies. In approximately 12% of patients, the right hepatic artery originates from the superior mesenteric artery, a variant described as a replaced right hepatic artery. Furthermore, an accessory right hepatic artery in addition to a conventional right hepatic artery was found in approximately 2.5% of patients in one cadaveric study. The left hepatic artery originates from the left gastric artery, also referred to as a replaced left hepatic artery, in approximately 4.5% to 6% of patients. In about 2% of patients, the common hepatic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery. The right hepatic artery then gives rise to the cystic artery, which furnishes the gallbladder with arterial blood. There is a single cystic artery in about 80% of patients. The cystic artery arises from the right hepatic artery about half the time, followed in decreasing prevalence by the accessory right hepatic, distal common hepatic, left hepatic, proximal common hepatic, proper hepatic, and gastroduodenal arteries. Two cystic arteries, usually both from the right hepatic artery, may be seen in approximately 19% of patients, whereas three cystic arteries have been found in less than 1% of those examined.5,6

The gastroduodenal artery is a short, vertically oriented branch of the common hepatic artery that often gives rise to the supraduodenal artery. In a study of 30 patients, the supraduodenal artery was identified in 93%, most frequently originating from the gastroduodenal artery. The supraduodenal artery supplies the distal two thirds of the upper portion of the duodenum and the supraduodenal and retroduodenal portions of the common bile duct. Anastomoses with the right gastric and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries were discovered in half of cases in a study by Bianchi and Albanese.7 The gastroduodenal artery then divides further into the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, and right gastroepiploic artery. The anterior and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries anastomose with the anterior and posterior branches of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery from the superior mesenteric artery, providing blood to the duodenum and surrounding pancreas.

Superior Mesenteric Artery

The superior mesenteric artery is the second large ventral branch of the abdominal aorta, typically emerging 1 cm below the celiac trunk, anterior to the first lumbar vertebral body. It supplies the midgut organs through its main (and largely intuitively named) branches, the inferior pancreaticoduodenal, jejunal, ileal, ileocolic, right colic, and middle colic arteries (Figs. 72-6 to 72-9). The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery supplies the head of the pancreas and duodenum. The superior mesenteric artery anastomoses with the anterior and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries originating from the gastroduodenal artery. Jejunal arteries form numerous anastomoses, resulting in extensive vascular arcades and collaterals supplying the jejunum and its mesentery. The ileocolic artery ramifies into multiple small branches, one of which is the appendicular artery supplying the appendix. The right and middle colic arteries deliver blood to the ascending colon and the proximal two thirds of the transverse colon and mesocolon.

Inferior Mesenteric Artery

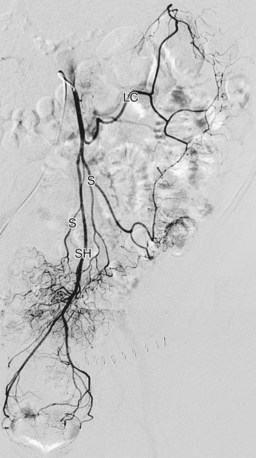

The inferior mesenteric artery is the most inferior of the visceral arteries from the abdominal aorta, generally located anterior to the L3 vertebral body. It supplies the hindgut through its major branches, the left colic artery, sigmoid artery, and superior rectal artery (Fig. 72-10). The left colic artery supplies the distal third of the transverse colon and descending colon and forms numerous vascular arcades and collaterals. The embryologic division between the midgut and hindgut is an area sensitive to ischemia, sometimes referred to as a watershed area of the transverse colon. The sigmoid arteries supply the distalmost aspect of the descending colon, along with the sigmoid colon. The superior rectal artery flows to the superior aspect of the rectum and forms copious collaterals with the middle and inferior rectal arteries, branches of the internal iliac and internal pudendal arteries, respectively.

Group 2: Renal and Adrenal Arteries

Group 2 includes branches supplying the kidneys and adrenal glands. The kidneys migrate superiorly from a sacral level during development and are progressively but transiently supplied by lateral aortic branches as they move up. Ultimately, the main renal arteries emerge between L1 and L2 in approximately 75% of the population, whereas the remaining 25% of individuals may have renal origins anywhere from the T12 through L2 vertebral levels. Anatomic variants are common, occurring in up to 40% of those studied.8,9 Accessory or aberrant vessels may arise from iliac, superior and inferior mesenteric, adrenal, inferior phrenic, right hepatic, intercostal, median sacral, lumbar, or right colic arteries. Patients with ectopic or horseshoe kidneys, or other renal anomalies, are more likely to demonstrate aberrant arterial origins. About 30% of individuals have supernumerary renal arteries and, of those, they are unilateral in about 30% and bilateral in about 10% of cases. Renal arteries taking origin from the aorta most frequently arise laterally, although infrequently the left renal artery arises posterolaterally and the right renal artery arises anterolaterally. Proximal division of the renal artery occurs in approximately 15% of individuals. Additionally, branching proximal to the renal hilum may provide blood supply to the proximal ureter, gonadal arteries, perinephric tissues, renal capsule, and/or adrenal glands. Knowledge of these renal variants is tremendously important for operative planning, and imaging for anatomic delineation is routine for renal donor candidates.

The three adrenal arteries are refined during the process of kidney ascension, which occurs by the sixth week of development. When the kidney has completed its upward migration, the superior adrenal artery begins to supply the maturing diaphragm, forming the inferior phrenic artery. Superior suprarenal artery branches from the inferior phrenic continue to supply the adrenal gland to varying degrees. Supplemental arterial supply comes from the middle suprarenal artery, which typically arises between T12 and L1, most commonly from the lateral aorta, although celiac, superior mesenteric, or lumbar artery origins have been demonstrated. The inferior suprarenal arteries are variable in their origin, in part related to the fact that the main renal arteries develop from the inferior adrenals during renal migration.10,11 Persistent arterial branches to the adrenal gland from the renal arteries occur in about 80% of individuals from the right and in 60% of individuals from the left. Some studies have shown that those with supernumerary renal arteries possess inferior adrenal branches with greater frequency. Furthermore, inferior suprarenal arteries may stem from renal capsular, inferior phrenic, or interlobar renal arteries.

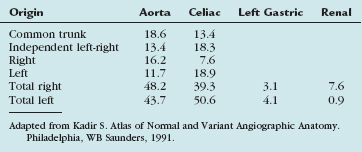

The inferior phrenic arteries provide blood supply to the abdominal aspect of the diaphragm and originate from the aorta and celiac axis with the highest and almost equal frequency, although numerous variant origins have been reported. The hepatic, superior mesenteric, left gastric, renal, and adrenal arteries have all been demonstrated to give origin to inferior phrenic arteries. If derived from the aorta, they are usually found between T12 and L2, but may be distributed from T9 to L2. The left and right inferior phrenic arteries may begin as a common trunk, or independently. Kadir has combined data from autopsy studies into a single table (Table 72-2).12

Group 3: Gonadal Arteries

Group 3 includes the gonadal arteries supplying the testes and ovaries. The gonadal arteries develop from lateral splanchnic branches of the abdominal aorta. Most commonly, gonadal arteries are single bilaterally and arise ventrally near the level of the second lumbar vertebra, taking a horizontal course (anterior to the inferior vena cava on the right) initially before diving caudally. Multiple gonadal arteries are more common on the left and a common origin, although rare, can emerge from either the aorta or renal artery. Approximately 5% to 20% arise superior to L2 and may originate from the main or accessory renal artery in up to 6% of individuals.13,14 A course posterior to the inferior vena cava may occur in cases of high right gonadal artery origin. Rarely, a gonadal artery arises from an adrenal, lumbar, or iliac artery. Closer to the gonadal arterial origin, branching supply to the ureter, perirenal adipose tissue, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes may be seen. Frequently tortuous distally, the ovarian artery provides tubal and ureteric branches in addition to supplying the ovaries and regions of inguinal skin.

Differential Considerations

A number of eponymous vascular anastomoses can hypertrophy as a result of flow limitations in the abdominal arterial system. Frequently, these anastomoses increase in prominence as atherosclerotic vascular narrowing progresses. For example, multiple collaterals exist between branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and between the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. The marginal artery of Drummond is formed by the anastomosis of a transverse branch of the middle colic artery with an ascending branch of the left colic artery.1,4 This artery is a marginal colonic artery that lies along the mesenteric border of the left colon. The arc of Riolan is a more medial anastomotic connection between the left colic and middle colic arteries (Fig. 72-11). The arc of Buehler is formed by the anastomosis of the celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery.

Fibromuscular disease is a nonatheromatous and noninflammatory process that causes arterial narrowing and aneurysms. While the cause of fibromuscular disease or dysplasia (FMD) is not well understood, the process tends to occur in women between the age of 40 and 60 years, frequently involves the renal arteries, and results in renovascular hypertension in about one-third of patients. Various forms of dysplasia or hyperplasia can involve the media, intima, or adventitia of the vascular wall. The most common type, medial fibroplasia (60% to 70%), produces alternating thick and thin fibromuscular ridges resulting in a string of beads appearance angiographically (Fig. 72-12). The mid to distal renal arteries are typically affected (60% to 75%), although abnormalities in the carotid and intracranial arteries (25% to 30%), mesenteric arteries (9%), and external iliac arteries (5%) may also be seen.

Pertinent Imaging Considerations

Capuñay C, Carrascosa P, Martín López E, et al. Multidetector CT angiography and virtual angioscopy of the abdomen. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:81-93.

Hazirolan T, Metin Y, Karaosmanoglu AD, et al. Mesenteric arterial variations detected at MDCT angiography of abdominal aorta. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1097-1102.

Iezzi R, Cotroneo AR, Giancristofaro D, et al. Multidetector-row CT angiographic imaging of the celiac trunk: anatomy and normal variants. Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30:303-310.

Smith CL, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Mesenteric CT angiography: a discussion of techniques and selected applications. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;9:150-155.

Zhang H, Zhang W, Juluru K, Prince M. Body magnetic resonance angiography. Semin Roentgenol. 2009;44:84-98.

1 LaBerge J, Gordon R, Kerlan R, Wilson W. Interventional Radiology Essentials. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

2 Larsen WJ, Sherman LS, Potter SS, Scott WJ. Development of the vasculature. In: Larsen WJ, Sherman LS, Potter SS, Scott WJ, editors. Human Embryology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2001:195-234.

3 Netter F. Atlas of Human Anatomy, 2nd ed. Altona, Manitoba, Canada: Friesens; 1997.

4 Gray H Anatomy of the Human Body, 20th ed Available at http://www.bartleby.com/107 Accessed September 27, 2009

5 Covey AM, Brody LA, Maluccio MA, et al. Variant hepatic arterial anatomy revisited: digital subtraction angiography performed in 600 patients. Radiology. 2002;224:542-547.

6 Nelson T, Pollak R, Jonasson O, Abcarian H. Anatomic variants of the celia, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries and their clinical relevance. Clin Anat. 1988;1:75-91.

7 Bianchi HF, Albanese EF. The supraduodenal artery. Surg Radiol Anat. 1989;11:37-40.

8 Fine H, Keen EN. The arteries of the human kidney. J Anat. 1966;100:881-894.

9 Harrison LH, Flye MW, Seigler HF. Incidence of anatomical variants in renal vasculature in the presence of normal renal function. Ann Surg. 1978;188:83-89.

10 Gagnon R. The arterial supply of the human adrenal gland. Rev Can Biol. 1957;16:421-433.

11 Toni R, Mosca S, Favero L, et al. Clinical anatomy of the suprarenal arteries: a quantitative approach by aortography. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;10:297-302.

12 Kadir S. Atlas of Normal and Variant Angiographic Anatomy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991.

13 Merklin RJ, Michels NA. The variant renal and suprarenal blood supply with data on the inferior phrenic, ureteral and gonadal arteries. J Int Coll Surg. 1958;29:41-76.

14 Asala S, Chaudhary SC, Masumbuko-Kahamba N, Bidmos M. Anatomical variations in the human testicular blood vessels. Ann Anat. 2001;183:545-549.

FIGURE 72-1

FIGURE 72-1

FIGURE 72-2

FIGURE 72-2

FIGURE 72-3

FIGURE 72-3

FIGURE 72-4

FIGURE 72-4

FIGURE 72-5

FIGURE 72-5

FIGURE 72-6

FIGURE 72-6

FIGURE 72-7

FIGURE 72-7

FIGURE 72-8

FIGURE 72-8

FIGURE 72-9

FIGURE 72-9

FIGURE 72-10

FIGURE 72-10

FIGURE 72-11

FIGURE 72-11

FIGURE 72-12

FIGURE 72-12