Chapter 29 Arm and Neck Pain

Clinical Assessment

History

Neurological Causes of Pain

Plexus Pain

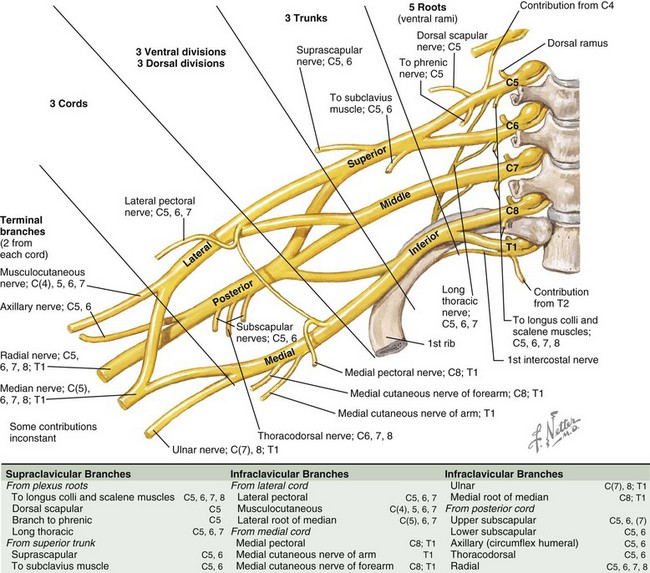

Peripheral pathology may involve the brachial plexus (Fig. 29.1) or individual nerves extending to the hand. Infiltrative or inflammatory lesions of the brachial plexus produce severe brachialgia radiating down the upper limb and also spreading to the shoulder region. Radiation to the ulnar two fingers suggests that the origin is in the lower brachial plexus, and radiation to the upper arm, forearm, and thumb suggests an upper plexopathy. Patients with a thoracic outlet syndrome complain of brachialgia and numbness or tingling in the upper limb or hand when working with objects above the head.

Examination

Motor Signs

The distribution of weakness is all important in localizing the problem to nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, muscle, or even upper motor neuron (central weakness). It is useful to use a simplified schema of radicular anatomical localization when evaluating nerve root weakness because overlap of segmental innervation of muscles can complicate the analysis (Table 29.1).

Table 29.1 Segmental Innervation Scheme for Anatomical Localization of Nerve Root Lesions

| Segment Level | Muscle(s) | Action |

|---|---|---|

| C4 | Supraspinatus | First 10 degrees of shoulder abduction |

| C5 | Deltoid | Shoulder abduction |

| Biceps/brachialis/brachioradialis | Elbow flexion | |

| C6 | Extensor carpi radialis longus | Radial wrist extension |

| C7 | Triceps | Elbow extension |

| C7 | Extensor digitorum | Finger extension |

| C8 | Flexor digitorum | Finger flexion |

| T1 | Interossei | Finger abduction and adduction |

| Abductor digiti minimi | Little finger abduction |

Sensory Signs

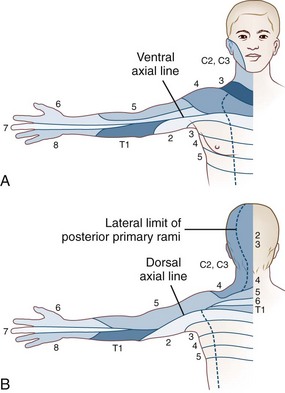

Skin sensation is tested in a standardized manner starting with pinprick appreciation at the back of the head (C2), followed by sequentially testing sensation in the cervical dermatomes, down the shoulder, over the deltoid, down the lateral aspect of the arm to the lateral fingers, and then proceeding to the medial fingers and up the medial aspect of the arm (Fig. 29.2). The procedure is repeated with a wisp of cotton to test touch sensation and test tubes filled with cold and warm water to test temperature sensation. Vibration sense is rarely abnormal in the fingers. Position sense in the distal phalanx of a finger is tested by immobilizing the proximal joint and supporting the distal phalanx on its medial and lateral sides and then moving it up or down; the patient, with closed eyes, reports movement and its direction. Loss of position sense in the fingers usually indicates a very high cervical cord lesion.

Pathology and Clinical Syndromes

Spinal Cord Syndromes

Extramedullary Lesions

Extramedullary lesions may result in any combination of root, central cord, and long-tract signs and symptoms. The most common cause of extrinsic nerve root and spinal cord compression is cervical spondylosis. This is a degenerative disorder of the cervical spine characterized by disc degeneration with disc space narrowing, bone overgrowth producing spurs and ridges, and hypertrophy of the facet joints, all of which can compress the cord or nerve roots. Hypertrophy of the spinal ligaments, with or without calcification, may contribute to compression. Hypertrophic osteophytes are present in approximately 30% of the population, and the incidence increases with age. The presence of such degenerative changes does not indicate that the patient has symptoms due to these changes; astuteness in diagnosis is necessary. Furthermore, the degree of bony change does not always correlate with the severity of the signs and symptoms it produces. This degenerative process is sometimes referred to as hard disc as opposed to an acute disc herniation or soft disc in which the onset is acute with severe neck pain and brachialgia. Patients with cervical spondylosis often awake in the morning with a painful stiff neck and diffuse nonpulsatile headache that resolves in a few hours. The lesion is most commonly at C5/6 and C6/7, and focal signs are likely to be at these levels. Wasting and weakness of the small muscles of the hands, particularly weakness of abduction of the little finger, is also frequently seen. These signs localize to lower segmental levels, but there may be no observable anatomical change at those levels, and then they are referred to as false localizers. Restricted neck movement is always present with significant cervical spondylosis. Bladder dysfunction, indicated by frequency, urgency, and urgency incontinence or the finding of long-tract signs or symptoms, indicates the need for imaging of the cervical spine both to exclude other pathology and to define the severity of the spinal cord compression. Immobilization in a cervical collar often helps with the symptoms and signs of cervical spondylosis. The role of surgery in treatment is discussed in Chapter 75.

Radiculitis

Herpes zoster may infect cervical sensory root ganglia. The pain is typically radicular, and the diagnosis becomes clear when, after 2 to 10 days, the typical vesicular rash appears. Motor involvement occasionally occurs, and when it does, it has a predilection for C5/6 segments. Myelitis with long-tract signs is seen in less than 1% of patients. If the pain lasts longer than 3 months after crusting of the skin lesions, postherpetic neuralgia has developed. The pain is described as constant, nagging, burning, aching, tearing, and itching, upon which are superimposed electric shocks and jabs. Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia pain is discussed in Chapters 69 and 75.

Brachial Plexopathy

Suprascapular Nerve Entrapment

The suprascapular nerve may be entrapped or injured as it passes through the suprascapular notch (see Chapter 76). It is occasionally cut in the process of lymph node biopsy. The branch to the infraspinatus muscle can be entrapped at the spinoglenoid notch by a hypertrophied inferior transverse scapular ligament. The patient complains of deep pain at the upper border of the scapula, aggravated by shoulder movement, and there may be atrophy and weakness of the supra- and more commonly the infraspinatus muscles. The supraspinatus muscle accounts for the first 10 degrees of shoulder abduction, and the infraspinatus muscle externally rotates the arm.

Ulnar Entrapment at the Elbow

The ulnar nerve may be entrapped proximal to the epicondylar notch or as it passes through the cubital tunnel at the elbow, where a fibro-osseous canal is formed by the medial condyle, ulnar collateral ligament, and flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. Structural narrowing of the canal aggravated by occupational stress and a sustained flexion posture, especially when sleeping, and repetitive flexion/extension movements contribute to entrapment. Although numbness and tingling are more common than pain, both are referred to the hypothenar eminence and the little and ring fingers. A positive Tinel sign at the elbow over the ulnar nerve helps localize the site. In severe cases, there is wasting and weakness of the small muscles of the hand (excluding the abductor pollicis brevis and opponens muscles which are median innervated). There is decreased sensation over the palmar aspect of the ring and little finger, and there may be decreased sensation on the medial dorsal aspect of the hand and ulnar two fingers owing to involvement in the distribution of the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve. In severe chronic cases, clawing of the fourth and fifth digits results from weakness of the third and fourth lumbrical muscles. Nerve conduction studies localize the area of entrapment. If the symptoms do not resolve by avoiding prolonged elbow flexion, and the physical signs are significant, surgical decompression should be considered (see Chapter 76).

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) encompasses syndromes previously called reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), causalgia, shoulder-hand syndrome, Sudeck atrophy, transient osteoporosis, and acute atrophy of bone (see Chapters 44, 76, and 77). By consensus, the syndrome requires the presence of regional pain and sensory changes following a noxious event. The pain is of a severity greater than that expected from the inciting injury and is associated with abnormal skin color or temperature change, abnormal sudomotor activity, or edema. Type I CRPS refers to patients with RSD without a definable nerve lesion, and type II CRPS refers to cases where a definable nerve lesion is present (formerly called causalgia). A soft-tissue injury is the inciting event in about 40% of patients, a fracture in 25%, and myocardial infarction in 12%.

Pain can be progressive, and three stages of progression have been described:

Stage I: sensations of diffuse burning, sometimes throbbing, aching, sensitivity to touch or cold, with localized edema. Vasomotor disturbances produce altered skin color and temperature.

Stage I: sensations of diffuse burning, sometimes throbbing, aching, sensitivity to touch or cold, with localized edema. Vasomotor disturbances produce altered skin color and temperature.

Stage II: progression of soft-tissue edema, with thickening of skin and articular soft tissues and muscle wasting. This may last 3 to 6 months.

Stage II: progression of soft-tissue edema, with thickening of skin and articular soft tissues and muscle wasting. This may last 3 to 6 months.

Stage III: progression to limitation of movement, often with a frozen shoulder, contractures of the digits, waxy trophic skin changes, and brittle ridged nails. Plain radiographs show severe demineralization of adjacent bones.

Stage III: progression to limitation of movement, often with a frozen shoulder, contractures of the digits, waxy trophic skin changes, and brittle ridged nails. Plain radiographs show severe demineralization of adjacent bones.

Autonomic testing may help with the diagnosis; the resting sweat output and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test used together are 94% sensitive and 98% specific and are excellent predictors of a response to sympathetic block. Bony changes including osteoporosis and joint destruction may be seen. Bone scintigraphy is most sensitive in stage I and less useful in later stages. A stellate ganglion block may be useful both therapeutically and diagnostically (see Chapter 76).

“In-Between” Neurogenic and Non-Neurogenic Pain Syndrome—Whiplash Injury

“Whiplash is an acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the neck. It may result from rear-end or side impact motor vehicle collisions but can also occur during diving or other mishaps. The impact may result in bony or soft tissue injuries (whiplash injury), which in turn may lead to a variety of clinical manifestations (whiplash-associated disorders).” – Québec Task Force on Whiplash Associated Disorders (Spitzer et al., 1995).

Grade I injuries: pain, stiffness, and tenderness in the neck—no physical signs

Grade I injuries: pain, stiffness, and tenderness in the neck—no physical signs

Grade II injuries: grade I symptoms together with physical signs of decreased range of movement and point tenderness

Grade II injuries: grade I symptoms together with physical signs of decreased range of movement and point tenderness

Grade III injuries: neurological signs are present—weakness, sensory loss, absent reflex or long-tract signs.

Grade III injuries: neurological signs are present—weakness, sensory loss, absent reflex or long-tract signs.

The prognosis is related to the severity of injury:

Neck pain longer than 6 months after injury: grade I, 44%; grade II, 81%; grade III, up to 90%

Neck pain longer than 6 months after injury: grade I, 44%; grade II, 81%; grade III, up to 90%

Headache longer than 6 months after injury: grade I, 37%; grade II, 37%; grade III, 70%

Headache longer than 6 months after injury: grade I, 37%; grade II, 37%; grade III, 70%

In general, about 40% of patients report complete recovery at 2 years, and about 45% continue to have major complaints 2 years after the injury.

In general, about 40% of patients report complete recovery at 2 years, and about 45% continue to have major complaints 2 years after the injury.

References

Alexander M.P. In the pursuit of principal brain damage after whiplash injury. Neurology. 1998;51:336.

Atroshi I., Gummesson C., Johnsson R., et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282:153.

Bajwa Z.H., Ho C.C. Herpetic neuralgia. Use of combination therapy for pain relief in acute and chronic herpes zoster. Geriatrics. 2001;56(12):18-24.

Carette S., Fehlings M.G. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-399.

Chamberlain M.C., Kormanik P.A. Epidural spinal cord compression: a single institution’s retrospective experience. Neurooncology. 1999;1:120-123.

Chance P.F., Windebank A.J. Hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy. Curr Opin Neurol. 1996;9:343-347.

Chelimsky T.C., Low P.A., Naessens J.M., et al. Value of autonomic testing in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:1029.

Cohen M.D., Abril A. Polymyalgia rheumatica revisited. Bull Rheum Dis. 2001;50:1-4.

Dreyer S.J., Boden S.D. Natural history of rheumatoid arthritis of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop. 1999;366:98-106.

Dymarkowski S., Bosmans H., Marchal G., et al. Three dimensional MR angiography in the evaluation of thoracic outlet syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:1005-1008.

Goldenberg D.L. Fibromyalgia syndrome a decade later. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:777.

Goldenberg D.L., Mayskiy M., Mossey C.J., et al. A randomized double-blind crossover trial of fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1852-1859.

Henderson R.D., Pittock S.J., Piepgras D.G., et al. Acute spontaneous spinal hematoma. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1145-1146.

Horch R.E., Allman K.H., Laubengerger J., et al. Median nerve compression can be detected by magnetic resonance imaging of the carpal tunnel. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:76.

Kim K.K. Acute brachial neuropathy—electrophysiological study and clinical profile. J Korean Med Sci. 1996;11:158-164.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K., Gilden D.H. Varicella-zoster virus infections of the nervous system: clinical and pathological correlates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:770-780.

Kuhlman K.A., Hennessy W.J. Sensitivity and specificity of carpal tunnel syndrome signs. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;76:838.

Landry G.J., Moneta G.L., Taylor L.M., et al. Long-term functional outcome of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome in surgically and conservatively treated patients. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:312-317.

Lawrence T., Mobbs P., Fortems Y. Radial tunnel syndrome. A retrospective review of 30 decompressions of the radial nerve. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1995;20:454-459.

Lee G.W., Weeks P.M. The role of bone scintigraphy in diagnosing reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20:458.

Leffert R.D., Perlmutter G.S. Thoracic outlet syndrome. Results of 282 transaxillary first rib resections. Clin Orthop. 1999;368:66-79.

Mackenzie A.R., Laing R.B., Smith C.C., et al. Spinal epidural abscess: the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:209-212.

Michiels J.J., Berneman Z., Schroyens W., et al. Platelet-mediated erythromelalgic, cerebral, ocular and coronary microvascular ischemic and thrombotic manifestations in patients with essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera: a distinct aspirin-responsive and Coumadin-resistant arterial thrombophilia. Platelets. 2006;17:528-544.

Obelieniene D., Schrader H., Bovim G., et al. Pain after whiplash: a prospective controlled inception cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:279.

Qayyum A., MacVicar A.D., Padhani A.R., et al. Symptomatic brachial plexopathy following treatment for breast cancer: utility of MR imaging with surface-coil techniques. Radiology. 2000;214:837-842.

Ronthal M. Neck Complaints. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 2000.

Rosenberg Z.S., Bencardino J., Beltran J. MR features of nerve disorders at the elbow. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 1997;5:545-565.

Salerno D.F., Franzblau A., Werener R.A., et al. Reliability of physical examination of the upper extremities among keyboard operators. Am J Industr Med. 2000;37:423-430.

Sampath P., Rigamonti D. Spinal epidural abscess: a review of epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:89-93.

Sheth R.N., Belzberg A.J. Diagnosis and treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2001;12:295-309.

Spitzer W.O., Skovron M.L., Salmi L.R., et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine. 1995;20:1S-73S.

Stanton-Hicks M., Janig W., Hassenbusch S., et al. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: changing concepts and taxonomy. Pain. 1995;63:127.

Swen W.A., Jacobs J.W., Bussemaker F.E., et al. Carpal tunnel sonography by the rheumatologist versus nerve conduction study by the neurologist. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:62.

Tong H.C., Haig A.J., Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2002;27:156-159.

Wainner R.S., Fritz J.M., Irrgang J.J., et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2003;28:52.

Wasner G., Schattschneider J., Heckmann K., et al. Vascular abnormalities in reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS I): mechanisms and diagnostic value. Brain. 2001;124:587.