18 Aquatic Physical Therapy

KEY POINTS

Hydrotherapy and aquatic therapy are often used interchangeably to refer to physical therapy performed in water. Spa therapy refers to physical modalities applied in a relaxing atmosphere that may be purely commercial, devoid of oversight from a licensed practitioner at point of delivery. Spa therapies can include land-based modalities such as massage and electrotherapy, as well as water-based forms such as balneotherapy and whirlpool. Spa treatments, even when water-based, are typically passive.1 Studies of spa interventions prove difficult. Balneotherapy refers to the immersion of patient or limb in a natural thermal mineral water, defined as at least 20° C, and containing a concentration of specific salts in excess of 1 g/L.1

Basic Science

Water is nearly 800 times as dense as air.2 The bottom of a mass of material exerts a pressure based on the density of the material. For example, at sea level, effectively at the “bottom” of the earth’s atmosphere, patients are exposed to the pressure of air. When a patient enters a body of water, be it a hot tub, swimming pool, or ocean, the water exerts pressure that increases with increasing depth. Water affects the cardiovascular and renal systems. Water’s hydrostatic pressure compresses veins, increasing venous return and pushing blood centrally, leading to a rise in central blood volume, cardiac blood volume, and cardiac output.3 Compression of veins can reduce edema. Healthy individuals seated for 2 hours in water from the renowned spa at Bath, England, showed a doubling of diuresis and 50% increase in cardiac index. The increase in diuresis is not due to an increase in creatinine clearance, though alteration of renally active hormones may play a role.4 It is unclear if hydrostatic pressure is the primary mechanism underlying all of these systemic effects.

Water is a viscous substance that resists movement. The resistance offered by the water increases as speed of movement increases, so when the patient first starts exercising in water, a slower velocity is naturally used. As strength and endurance improve, faster movement is possible with greater challenge. Because of the mechanics of fluid, resistance is maximized if the patient performs exercises in a continuous movement in which the limb is kept below the water surface. Resistance can be strategically lessened to accommodate the patient’s strength level with partial submersion and pausing during the movement. For the stronger patient, water mitts and hand paddles can be added to increase drag of the limb.5 Training in water has several advantages compared to land. Movements against water are inherently more difficult than identical movements against air because of water’s viscosity, making virtually any movement against water a resistance training exercise. Performing resistance training movements in water puts less stress on joints because they are unloaded of gravitational forces compared to land.

Pain decreases in water through several mechanisms. The natural buoyancy of water unloads joints and supports the body so less muscle activation and coordination is required to maintain balance. Standing upright with water up to the neck, the upward buoyant force counteracts gravity so that about 10% of the normal gravitational force is exerted on the body. Discs, facets, and peripheral joint structures are unloaded allowing for functional movements such as walking with less stress.6 Reduction of muscle activity to maintain balance allows for easier control of proper pelvic tilt and lumbar curvature. Body support from buoyancy in positions of spinal flexion and extension means the patient can actively range through normally painful spinal load movements with less compression on the spine. Normal range of motion may be achieved in a pain-free manner in the aquatic environment before trying similar exercises on land.5 A negative effect of buoyancy is a decrease in body stability with water levels above the T8 spinal level. Shallower water may be indicated if the patient has difficulty keeping his or her feet planted on the pool floor.5 An additional factor in aquatic therapy pain relief is that water acts as a diffuse sensory stimulus that can alter or suppress the typical pain experience.5

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Physician Evaluation and Prescription

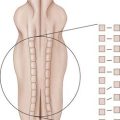

While obtaining the history and physical the practitioner will pay special attention to factors that will make aquatic therapy uniquely beneficial, as well as to contraindications. Evaluation includes a focused neurologic and musculoskeletal examination with a focus on spinal range of motion, strength, sensation, and gait. A common example of an aquatic therapy regimen is that outlined by Dr. Andrew Cole.7 Static and dynamic exercises of progressive difficulty are used for development of spinal stabilization. Examples include sitting against the pool wall with neutral spine posture, walking forward and backward, abdominal crunches, a host of exercises designed for the facilitation of neutral spine posture, flexibility, conditioning and core strength.

Indications

Indications for water therapy are similar to those for land-based therapies with the most important criterion being unsuitability for a fully land-based program. The patient may need extra support due to weakness or proprioceptive loss and concurrent land-based spinal rehabilitation is possible if the patient can tolerate some land-based exercises.7 Ultimately the patient needs to function on land in an air atmosphere without the support and comfort of water. Aquatic therapy can be used to decrease pain, and improve gait, strength, endurance, or coordination. In water, skills can be simulated in a less challenging setting than land with the ultimate goal being improved function and pain level while on land. The water milieu can serve as a bridge to improved land function.5

Contraindications

There are general contraindications for use of any form of water immersion including home bathing. These include open wounds, fever, severe heart disease, bowel or bladder incontinence, open ports such as tracheostomy, feeding tube, or colostomy, and extreme cognitive or functional impairment rendering a water environment unsafe.5

Evidence Base

High quality evidence supporting the efficacy of water therapy for pain relief and functional restoration in patients with spinal disorders has been limited, with the practice supported primarily by anecdotal reports and extrapolation from studies of peripheral joint arthritis. The purported special ability of aquatic therapy to reduce pain has been challenged in a recent meta-analysis. Hall et al.8 conducted an exhaustive search of 18 databases for studies of water therapy in the treatment of pain for neurologic or musculoskeletal conditions. The authors distilled the 793 identified studies down to 19 that were of adequate quality with sufficient data to analyze. Three of the included studies were of chronic low back pain, while the remaining were of rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and multiple sclerosis. The authors found that in aggregate there was no additional pain-relieving effect of aquatic therapy compared to land-based therapies. When compared with no treatment at all, aquatic therapies provide a small amount of pain relief.8 These results do not eliminate the possibility of water-specific pain-relieving properties. The pain-relieving effect may be the same for land- and water-based therapies yet their mechanisms may differ. For the individual unable to tolerate land-based therapies aquatic therapies are a means to seek a pain-relieving effect.

A useful resource for clinicians interested in exploring the evidence base for water therapies is http://aquaticnet.com/index.htm, an online repository of references for scholarly and non-scholarly writings on water therapies.

1. Bender T., Karagulle Z., Balint G.P., Gutenbrunner C., Balint P.V., Sukenik S. Hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, and spa treatment in pain management. Rheumatol. Int. 2005;25(3):220-224.

2. Tipler P.A. Physics for scientists and engineers, third ed. New York: Worth Publishers; 1991.

3. Becker B.E., Andrew Cole, J: Aquatic rehabilitation. In DeLisa J.A., editor. Physical medicine and rehabilitation, 4 ed., Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005;479-492.

4. O’Hare J.P., Heywood A., Summerhayes C., Lunn G., Evans J.M., Walters G., et al. Observations on the effect of immersion in Bath spa water. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.). 1985;291(6511):1747-1751.

5. McNeal R.L. Aquatic therapy for patients with rheumatic disease. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 1990;16(4):915-929.

6. Konlian C. Aquatic therapy: making a wave in the treatment of low back injuries. Orthop. Nurs. 1999;18(1):11-18. quiz 19–20

7. Andrew J., Cole R.E.E., Moschetti Marilou, Sinnett Edward. Aquatic rehabilitation of the spine. Rehab. Management (April/May). 1996:55-62.

8. Hall J., Swinkels A., Briddon J., McCabe C.S. Does aquatic exercise relieve pain in adults with neurologic or musculoskeletal disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008;89(5):873-883.