18 Approach to the Pediatric Patient with a Rash

• Rashes with fever deserve special consideration, especially if the fever has been present for more than 5 days.

• Palpable petechiae and fever are associated with many types of bacteremia and should be treated with intravenous antibiotics immediately.

• Many pediatric exanthems are benign in children but potentially devastating to pregnant women and immunocompromised patients.

• Patients who are moderately to critically ill with evidence of rash should receive targeted empiric therapy.

• The mainstay of treatment of atopic dermatitis is topical corticosteroids.

• Diaper dermatitis present for more than 3 days is usually complicated by candidal infection.

• Staphylococcal scaled skin syndrome and toxic shock syndrome require antistaphylococcal antibiotics, hemodynamic stabilization, and supportive skin care.

Introduction

Children are often brought to the emergency department with rashes ranging from the inconsequential (insect bites) to life-threatening emergencies (meningococcemia). When evaluating a rash, physicians should be systematic in the creation of an appropriate differential diagnosis, with early identification of possible life-threatening dermatologic conditions. Assessment of the distribution, morphology, and quality of the rash is of paramount importance. Detailed historical data regarding systemic symptoms and antecedent events are required. Please refer to Chapter 191 for the approach to undifferentiated rash. This chapter addresses dermatologic conditions most commonly diagnosed in pediatric patients.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

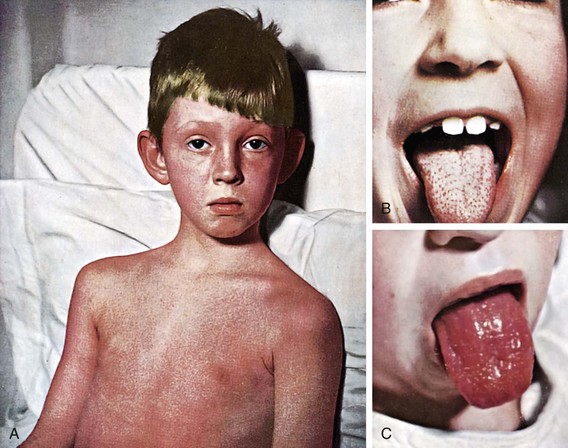

Classic Exanthems and Viral Rashes

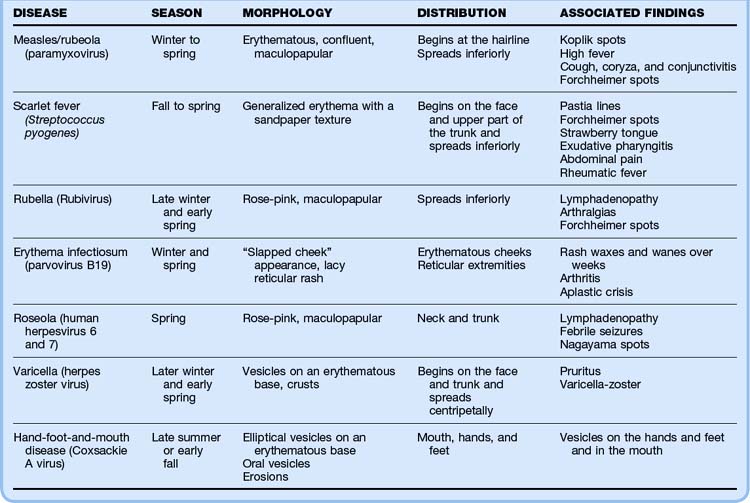

Historically, six infectious exanthems were originally described: measles or rubeola (first), scarlet fever (second), rubella (third), Dukes disease (fourth), erythema infectiosum (fifth), and exanthema subitum or roseola infantum (sixth).1 The majority of childhood exanthems are nonspecific and cannot be accurately assigned to a discrete etiologic diagnosis. These exanthems are typically self-limited and resolve spontaneously within a week.2 Table 18.1 details these classic exanthems and viral rashes.

Measles

Measles is rarely seen in developed countries because of the widespread use of vaccination. However, measles continues to affect the populations of developing countries.3,4 In 1997 it was the sixth leading cause of death worldwide; it is still the leading cause of blindness in African children.5 The causative agent of measles is paramyxovirus, which has an incubation period of 7 to 12 days, and infection occurs most commonly in winter and spring.1,6 Measles is contagious 3 days before and 5 days following onset of the rash. It begins with a prodrome of gradually increasing fevers (>40° C), headache, coryza, dry hacking cough, and an impressive bilateral conjunctivitis (the three C’s). The prodrome occurs 2 to 4 days before the rash.7 Koplik spots are clustered, white lesions (“grains of salt on a wet background”) that may appear on the buccal mucosa opposite the second molars during the prodromal period (Fig. 18.1). They are pathognomonic if present.7 The erythematous, nonpruritic, maculopapular rash first appears at the hairline and behind the ears and then spreads inferiorly. As the rash involves the trunk and extremities, the discrete macules coalesce. After 1 week the rash fades.1,6 Diagnosis of measles is typically made clinically; however, laboratory diagnosis via serologic assay is available.7,8 Treatment of measles is supportive. Administration of vitamin A is associated with a reduction in risk for mortality in children younger than 2 years, as well as a reduction in postmeasles pneumonia complications.9 Complications of measles include blindness, pneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, otitis media, myocarditis, and encephalitis.7,10

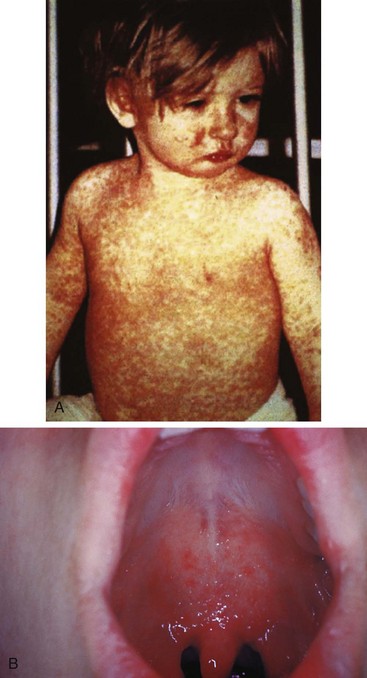

Scarlet Fever

Scarlet fever, an exotoxin-mediated illness caused by infection with Streptococcus pyogenes, occurs primarily in children younger than 10 years.11 Scarlet fever is most often associated with streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis, although it can be seen following other streptococcal infections.12 Its incidence is highest during the late fall to late winter, and the incubation period is 2 to 5 days.12,13 Symptoms include an abrupt onset of fever, headache, malaise, and odynophagia with occasional vomiting and abdominal pain. This is followed by the appearance of a strawberry tongue and a bright red enanthem (oral rash) on the soft palate and uvula. These punctate, erythematous macules are called palatal petechiae or Forchheimer spots. The rash, which follows the fever by 1 to 2 days, is a generalized erythroderma with scattered pinpoint, erythematous blanching papules that have a sandpaper-like texture. Capillary fragility causes petechiae in the flexural surfaces (Pastia lines), and facial flushing with circumoral pallor is often apparent. The palms and soles are typically spared. The exanthem typically resolves in 5 days, followed 2 weeks later by postexanthematous desquamation, especially of the palms and soles.1,11 The diagnosis is made clinically but can be confirmed by streptococcus-positive throat culture.11 Penicillin remains the treatment of choice to prevent local suppurative complications and acute rheumatic fever.13 Additional complications are rare but include sepsis, acute glomerulonephritis, pneumonia, pericarditis, hepatitis, otitis media, meningitis, and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) (Fig. 18.2).11,14

Fig. 18.2 Scarlet fever.

(Courtesy Dr. Franklin H. Top, Professor and Head of the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, State University of Iowa, College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA; and Parke, Davis & Company’s Therapeutic Notes. From Gershon AA, Hotez PJ, Katz SL. Krugman’s infectious diseases of children. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.)

Rubella

Rubella is a relatively mild illness caused by Rubivirus that is accompanied by a maculopapular rash. The incubation period is 12 to 23 days, with the period of infectivity extending from a few days before until 7 days following onset of the rash.15 Rubella occurs most commonly in late winter and early spring.15 The prodrome is mild, if present, and consists of malaise, pharyngitis, cough, low-grade fever, coryza, and a headache. A faint pink-red maculopapular rash subsequently appears, first on the face and then with rapid caudal spread. The rash typically resolves in 3 to 4 days.15,16 The prodrome is common in adolescents and adults but is often absent in younger children. Other clinical findings include posterior cervical and occipital lymphadenopathy, Forchheimer spots, arthralgia, and neutropenia.1,16 The diagnosis is made clinically but serologic tests are available.16 Treatment of rubella is supportive. However, patients must avoid pregnant women (first 20 weeks of gestation) to prevent spontaneous abortion or congenital rubella syndrome.15 Complications of rubella include arthritis, encephalitis, and thrombocytopenia.15,17

Erythema Infectiosum

Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) is caused by human parvovirus B19 and typically affects school-age children. It has an incubation period of 1 to 2 weeks and occurs more frequently in winter and spring.1,15,18 Children with this virus typically feel well. However, 10% of patients experience a prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, headache, sore throat, malaise, myalgia, and coryza.1,18 This prodrome is followed by a bright, fiery red macular rash across the cheeks that gives the child a “slapped cheek” or sunburned appearance. This rash lasts 1 to 4 days and then progresses to a more generalized rash with a lacy reticular pattern, most prominent on the extremity extensor surfaces. The rash may then wax and wane for a month, with various stimuli increasing its intensity.1,15 Once the rash appears, children are no longer infectious.1 The diagnosis is made clinically, but serologic tests can be used. Treatment of erythema infectiosum is supportive, but parents must keep infected children away from pregnant women and those with hemolytic anemia. High-risk groups may be treated with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG).15 Complications are rare but include symmetric arthritis of the hands, wrists, or knees and intrauterine infection and fetal death if the infection occurs during the first half of pregnancy. Children with hemolytic anemia and hemoglobinopathy (particularly sickle cell disease) are prone to transient aplastic crisis when infected with parvovirus.18–21

Roseola Infantum (Exanthema Subitum)

Roseola is the most common viral exanthem in children younger than 3 years. It is called baby measles or 3-day fever, and the causative agents are human herpesviruses 6 and 7.22,23 Roseola has an incubation period of 5 to 15 days.15,24 It is characterized by high fever for 2 to 5 days in an otherwise well-appearing child. Following dissipation of the fever, a blanching, evanescent, pink maculopapular exanthem develops on the neck and trunk. The rash typically lasts approximately 1 to 2 days. Associated symptoms include mild coryza, cough, otitis media, headache, periorbital edema, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy.23–25 An enanthem of red papules (Nagayama spots) may be seen on the mucosa of the soft palate and uvula.23,25 The diagnosis is made clinically and treatment is supportive.15,24,26 Febrile seizures are a common complication. Other complications are uncommon but include thrombocytopenia, hepatitis, and encephalitis.15,24,27

Varicella (Chickenpox)

The incidence of varicella has decreased 90% in the last 20 years with routine vaccinations.28 Chickenpox, caused by varicella-zoster virus, is highly contagious, with a peak incidence in late winter and spring.29,30 Children 2 to 8 years of age are primarily affected. After an incubation period of 10 to 21 days, the prodrome begins with malaise, low-grade fever, cough, coryza, anorexia, sore throat, and headache.30,31 Within 1 to 2 days the skin eruption begins on the trunk and then spreads over the next week to the face (including the mucous membranes) and extremities (with sparing of the palms and soles). The lesions begin as red macules that quickly progress to discrete vesicles on an erythematous base (Fig. 18.3). The vesicles (“dew drops on a rose petal”) rapidly evolve into pustules, which umbilicate and crust over in 5 to 10 days. These lesions are intensely pruritic and characteristically seen in all stages of development at once, with resolution in 7 to 10 days.1,30 The infectivity period begins several days before onset of the rash and lasts until all the lesions are completely crusted.31 The diagnosis is made clinically; however, a Tzanck preparation demonstrating multinucleated giant cells or other viral assays can be used for confirmation.1,30 Treatment is usually supportive, with management of constitutional symptoms and pruritus and prevention of secondary infection.1,30 Wet dressings, soothing baths, calamine lotion, and antihistamines may provide symptomatic relief. Acyclovir may be effective in treating varicella and preventing systemic complications in immunocompromised children. The role of acyclovir in otherwise healthy children remains unclear.32,33 In normal, immunocompetent children, symptoms are mild and serious complications rare. Secondary bacterial infections should be treated with antibiotics directed at Staphylococcus aureus or group A β-hemolytic streptococci (cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or dicloxacillin).1 Mupirocin may be appropriate for minor, localized secondary infections. Other complications include pneumonia, vasculitis, and encephalitis.34 Immunocompromised children and patients receiving chronic steroid treatment are more prone to extensive skin eruptions, varicella pneumonia, and severe constitutional symptoms.35 Maternal infection (first trimester) can result in congenital varicella syndrome. Perinatal maternal infection can result in disseminated herpes of the neonate.30,31 Perinatal varicella carries a mortality of up to 30%.31

Picornaviral Exanthems

Picornaviruses are a family of RNA viruses that cause a variety of illnesses. Common viruses include coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and enteroviruses. These are the most common summertime exanthems.1,22 Disease expression ranges from exanthems (younger children) to aseptic meningitis (older children). The characteristic exanthem is typically morbilliform (“measlelike”).1 Associated symptoms include upper respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis, fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. Complications include pericarditis, myocarditis, pleurodynia, parotitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, and encephalitis.1

Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease

This enteroviral exanthem is caused by Coxsackie A virus and enterovirus 71. It is characterized by oral vesicles, followed by vesicles on the hands and feet and may also include the buttocks.15 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease has an incubation period of 3 to 6 days.36 Patients are highly contagious 2 days before and 2 days following onset of the eruption. There is a brief prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, and odynophagia. The oral lesions begin as small red macules that evolve into vesicles measuring 2 to 20 mm. These vesicles rupture rapidly and leave painful erosions. Children often refuse to eat or drink because of pain, and dehydration is a potential complication.15,36 The lesions found on the hands and feet begin as macules and papules that evolve into flat-topped, elliptical vesicles with an erythematous base. The diaper area may be affected in infants.1 The diagnosis is made clinically, and treatment is symptomatic. Anesthetic mouthwash may provide relief from painful oral ulcers.15 Rare complications include myocarditis, pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, and aseptic meningitis. Infection during the first trimester of pregnancy may result in spontaneous abortion (see Table 18.1).15

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

These infections represent the most common bacterial, fungal, and viral infections of childhood. Table 18.2 details these pediatric skin and soft tissue infections.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial skin infection typically caused by S. aureus or S. pyogenes and is the most common cutaneous infection in children.1,32 Impetigo is most prevalent in children younger than 6 years and typically occurs in late summer and early fall secondary to microscopic breaks in the epidermal barrier.12,37,38 Additional contributing factors include warm humid climates, overcrowding, and poor hygiene.12 Impetigo is highly communicable.37 Variants of impetigo include bullous impetigo and impetigo contagiosa. Bullous impetigo is seen most often in neonates and is caused by S. aureus phage group II. The lesions of bullous impetigo commonly occur in the periumbilical or perineal region in neonates and on the extremities in older children. The lesions are flaccid, thin-walled bullae that when ruptured leave shiny, rounded erythematous erosions with peeling edges (“coin lesions”).39,40 Associated lymphadenopathy is rare and the Nikolsky sign is negative. Impetigo contagiosa is the most common variant and is caused by S. aureus or group A β-hemolytic streptococci.38 The rash begins as small painless erythematous macules, commonly near the nose and mouth, which then progress to small vesicles and pustules with erythematous margins. These lesions rupture easily and release a serous fluid, which dries to form a honey-colored crust.38,39 Associated regional lymphadenopathy is common. Topical antibiotics, such as 2% mupirocin, are often effective for limited infections.37,40,41 However, extensive lesions may be treated with 10 days of oral antibiotics directed at Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Suggested antibiotics include cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, dicloxacillin, and oxacillin.32,37,39 The nose may serve as a reservoir of staphylococci, and children with recurrent impetigo may benefit from a course of intranasal mupirocin.1 Though rare, poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is the most significant complication of streptococcal impetigo.12,38 Although systemic antibiotics help eliminate the cutaneous lesions of impetigo, they do not prevent poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis.37 Other complications include local spread, cellulitis, regional lymphadenitis, staphylococcal scaled skin syndrome (SSSS), scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, and sepsis.38

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a distinctive form of cellulitis that affects mainly infants, young children, and the elderly.22 It is caused by group A streptococci.32,33 Erysipelas affects only the upper dermis, whereas the more classic cellulitis also involves the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat.12,43 Erysipelas occurs most commonly on the face or lower extremities, although any area of the body may be affected.43 The lesions appears as warm, tender, shiny, erythematous plaques with raised and sharply demarcated borders.22,43 Rapid spread is the rule, and lesion blistering can occur. Associated signs and symptoms include high fever, chills, and anorexia.22 The diagnosis is made clinically.44 Treatment with penicillin plus clindamycin is recommended, and the combination may be associated with better outcomes than monotherapy.

Tinea

Tinea is a general term used to describe a collection of skin mycoses, including tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), tinea cruris (jock itch), tinea corporis (ringworm), and tinea capitis (scalp). These dermatophytes invade the dead keratin of skin, hair, and nails.45 The most common offending fungi are Microsporum canis and Trichophyton tonsurans.46,47 Tinea capitis is rarely seen past adolescence, whereas tinea pedis and cruris are usually seen in adolescents and adults.46 Tinea corporis produces annular, erythematous, pruritic patches with a scaly leading edge.45 Treatment of tinea corporis, cruris, and pedis includes topical antifungal preparations such as miconazole or clotrimazole for 2 to 4 weeks.48 Tinea capitis is characterized by scaly discrete patches of alopecia. It is the most common dermatophytosis of childhood.45 Most cases occur in children 4 to 7 years old, with a predilection for African Americans.49 Clinical findings vary from scaling and patchy hair loss to pruritic papules, pustules, and crusting.49 Occipital and posterior cervical adenopathy is usually present.45 Additionally, “black dots,” or short broken-off hairs, may be seen at the scalp surface.47 A kerion (tender boggy abscess devoid of hair) occasionally develops as a severe inflammatory reaction to the fungus.47,49 A Wood lamp can aid in the diagnosis of tinea capitis. Hairs infected with Microsporum will fluoresce blue-green. Wood lamp evaluation is not helpful in the diagnosis of tinea infections on hairless skin. Alternatively, direct KOH microscopy of skin scrapings can also be used for diagnosis.45,47 Treatment of tinea capitis consists of 6 to 8 weeks of oral griseofulvin and a selenium sulfide shampoo twice weekly.45,46 Treatment with griseofulvin mandates monitoring of liver function. Alternative treatment regimens consisting of terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole may also be effective.46 Contaminated hairbrushes, towels, pillows, and hats should be disinfected.

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum is a common childhood viral infection of the skin characterized by umbilicated papules. It is caused by a poxvirus and can occur at any age but is most common in young children and those with impaired cellular immunity.50,51 Molluscum is contagious and seen frequently in swimmers, wrestlers, and sexually active persons. Those with atopic dermatitis and immunosuppression are especially susceptible.50,51 The incubation period ranges from 2 to 8 weeks. The lesions are discrete skin-colored, dome-shaped papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter and usually umbilicated.51,52 The lesions are typically painless and nonpruritic. They occur (alone or in groups) on the face, chest, axilla, and upper extremities. The diagnosis is made clinically.51 A single lesion may be treated with cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) or by evisceration of the core with a comedone extractor, sterile needle, or scapel.52 Treatment of multiple lesions includes the application of cantharidin, retinoic acid, or benzoyl peroxide.51 If untreated, most lesions resolve spontaneously in less than a year.51,52

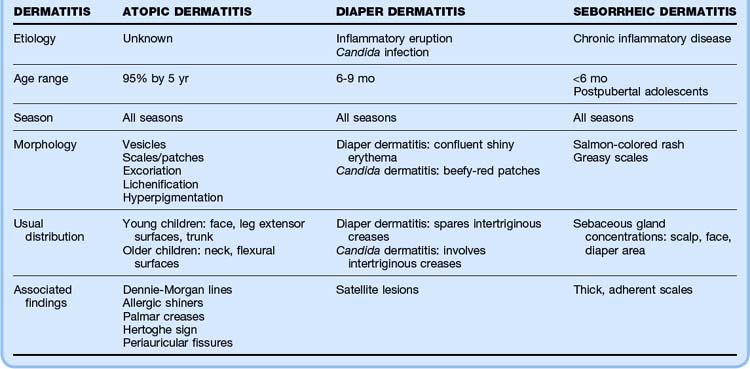

Dermatitis

Dermatitis is a general term used to refer to a collection of conditions producing a pruritic, inflammatory, noninfectious rash. Table 18.3 outlines these pediatric dermatitis conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD), commonly referred to as eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritus, erythema, vesicles, and scales. Once chronic, AD can also appear lichenified and hyperpigmented.1,45 AD is more commonly diagnosed in children with a family history of atopy (allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis).1 Nearly 95% of patients in whom eczema is diagnosed are identified by 5 years of age.1 The lifetime prevalence of AD is approximately 17%.53 Although the exact cause is unknown, eczematous skin is postulated to have a decrease in skin lipids and thus altered water-binding capacity. This leads to marked skin dehydration, pruritus, and scratching, which results in the characteristic skin lesions.53 In young infants, scaly, erythematous papules, patches, or vesicles commonly erupt on the face, the extensor surfaces of the legs, and less commonly the trunk. Approximately 50% of young infants in whom eczema is diagnosed have complete resolution of symptoms by 3 years of age. In older children, eczematous lesions tend to be found in the flexural surfaces and the neck. These lesions appear scaly and erythematous, often with crusts, excoriation, and lichenification. Of note, eczematous lesions in dark-skinned individuals frequently occur on extensor rather than flexural surfaces and are more papular and hyperpigmented in appearance. Treatment of AD includes behavioral changes, emollients, topical corticosteroids, and antihistamines.1,53 Fragrances and bubble baths should be avoided. Mild, unscented moisturizing soaps (Dove, Aveeno) are preferred. Irritants such as overly hot water, synthetic fabrics, wool, stuffed toys, bleach, and fabric softeners should be avoided. Long-sleeved cotton shirts can protect the skin. Patients with AD should apply emollients (Aquaphor, Eucerin) after bathing while the skin is still moist to prevent flare-ups. Corticosteroids should be applied to areas of acute exacerbation to reduce and eliminate inflammation.53 Ointments are preferred because they penetrate more efficiently and provide a more effective barrier against moisture loss than creams do. However, they may be less tolerable during the summer months. Low- to intermediate-potency steroids are recommended for the initial management of AD in older children and adolescents. Infants and young children should be treated with one of the lower-potency topical steroids (1% hydrocortisone). High-potency steroids are not usually required for the treatment of eczema except in regions with long-standing lichenified or intractable plaques.1 Corticosteroids should be applied one to three times daily until the inflammation subsides. The least potent topical steroids should be applied to the face, axilla, and groin because these areas are especially prone to atrophy.1 Pruritus can be treated with antihistamines (hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine). Localized infection should be treated with oral antibiotics effective against S. aureus (cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or azithromycin).1

Diaper Dermatitis

Diaper dermatitis is not one specific entity but incorporates all inflammatory eruptions occurring in the diaper area, including irritant diaper dermatitis and Candida diaper dermatitis. Diaper dermatitis has a prevalence of 7% to 35% and a peak incidence at about 6 to 9 months of age. Diaper dermatitis is triggered by the moist, occluded, macerated milieu of the diaper region. Other irritants include friction, diaper detergents, disinfectants, an alkaline pH, and fecal material.54 Precipitating factors include infrequent diaper changes, insufficient bathing and cleansing, and especially occlusive diapers.55 The rash typically begins over areas where friction is most pronounced, such as the buttocks, genitals, lower part of the abdomen, and inner aspect of the thighs. It begins as confluent shiny erythema with minimal scale that spares the intertriginous creases. Secondary infection with Candida albicans leads to progression of the eruption to a moist, beefy-red patch. Satellite lesions may be appreciated at the periphery.56 Unlike simple irritant diaper dermatitis, Candida diaper dermatitis results in intertriginous involvement. Candida has been isolated in up to 80% of children with diaper dermatitis present for more than 3 days. Prevention and treatment of diaper dermatitis are typically achieved with simple measures to decrease irritation in the diaper region. Such measures include frequent diaper changes, the use of highly absorbent diapers, avoidance of cloth diapers, diaper-free periods, and avoidance of plastic or rubber diaper pants.55 The diaper region should be cleansed gently with mild soap and dried completely. Use of barriers such as zinc oxide, petroleum, or talcum powder may help protect the skin from maceration. Candidal superinfection is treated with topical antifungal cream such as nystatin, clotrimazole, or miconazole.57

Seborrheic Dermatitis (Cradle Cap)

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology with a bimodal distribution—infants younger than 6 months and postpubertal adolescents and young adults. It appears as a salmon-colored rash with overlying diffuse greasy yellow or white scales occurring in areas with high sebaceous gland concentration. Lesions are typically located on the scalp but may spread to involve the forehead, nasal folds, eyebrows, and diaper area. The lesions are not typically pruritic or painful.1,58 Seborrheic dermatitis can be treated successfully with oatmeal baths and antiseborrheic shampoo (tar shampoo, selenium sulfide).58 Ketoconazole has been shown to be effective. If the scales are particularly thick or adherent, loosening of the scales with warmed mineral oil and use of a fine-toothed comb before shampooing hasten clearing.1 If the lesions are especially resistant to these treatments, corticosteroid preparations may be used.

Severe Pediatric Rashes

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a small-vessel vasculitis characterized by a purpuric rash, abdominal pain, arthritis, and hematuria.59 It is usually seen in children between 3 and 10 years of age. HSP is often preceded by an upper respiratory infection or drug exposure.59 The pathophysiology of HSP involves deposition of immunoglobulin A, C3, and immune complexes onto small vessels, which leads to systemic inflammation.59 The HSP classic triad consists of purpura, abdominal pain, and arthritis. The purpura is palpable and most commonly found in a symmetric distribution over the buttocks and extensor surfaces of the legs. The abdominal pain is colicky and may be associated with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloody stools, or intussusception.59,60 Hematuria occurs in 10% to 20% of cases, and end-stage renal disease develops in approximately 1% of children.59 The diagnosis of HSP is made clinically; however, a blood count, coagulation studies, chemistry panel, and urinalysis should be performed to exclude other diagnoses and evaluate renal function. HSP is a self-limited illness and treatment is supportive. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to reduce pain in the joints and soft tissue. The use of corticosteroids remains controversial.59 Patients should be hospitalized if complications such as significant bleeding, intussusceptions, or renal failure develop.

Meningococcemia

One of the most feared infections in the emergency department is meningococcemia caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. Although meningococcus is relatively rare in the United States, it is uniformly fatal, usually within 24 hours, if untreated.61,62 This diagnosis must be considered in any child with fever, headache, and a rash. Meningococcemia may be manifested as a flulike illness with fever, myalgia, vomiting, and arthralgia. In up to two thirds of patients, the early, morbilliform (“measlelike”) rash may mislead the physician into making the diagnosis of a viral exanthem.63 The disease progresses quickly and exhibits more specific signs: nuchal rigidity, photophobia, altered mental status, and a petechial or purpuric rash. The rash most commonly involves the trunk and lower extremities; however, petechiae may also appear on the face, palms, and mucous membranes. As the infection proceeds, more extensive hemorrhagic lesions are seen on all body areas and progress to large ecchymotic areas.62,63 Evaluation of patients with suspected meningitis should include blood cultures, serum chemistries, and a lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis and culture. If meningococcemia is suspected, antibiotics should be administered expeditiously (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, plus vancomycin). Additional treatments include admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), fluid resuscitation, steroids, vasopressor agents, and prophylactic treatment of close contacts.61–64

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

SSSS is a potentially life-threatening, toxin-mediated disease manifested by tender blistering and widespread desquamation. It usually occurs in children younger than 5 years.11 The pathophysiology of this illness in children is postulated to be lack of antibodies against the toxin and reduced toxin excretion in comparison with adults.63 The etiologic agent is exotoxin-producing S. aureus of phage group II.11 The initial staphylococcal infection typically involves the nasopharynx, umbilicus, urinary tract, cutaneous wounds, conjunctiva, or blood. Symptoms of SSSS include a sudden onset of fever and irritability, followed by slight diffuse erythema (resembling a sunburn) and cutaneous tenderness (the infant does not want to be held). The rash initially affects the perioral and periorbital regions, neck, axilla, and groin. This is followed by the crusting exfoliative phase, which occurs around the mouth and eyes. Flaccid bullae also develop. Gentle traction on the affected skin results in epidermal separation (Nikolsky sign), which leaves a shiny, moist, red surface. The mucous membranes are not involved.11,61,63 In newborns, the entire skin surface may be involved (Ritter disease). In SSSS, the cleavage plane for skin sloughing is epidermal. In toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), the cleavage plane is at the dermal-epidermal junction. Therefore, in SSSS only the epidermal layer is shed, thus resulting in less morbidity than that occurring with TEN.63 The diagnosis is made clinically. Complications include sepsis and respiratory distress. Treatment is directed toward elimination of active S. aureus infection to eradicate toxin production. Patients are typically treated with a β-lactamase penicillin or clindamycin. Although antibiotics are recommended, it is unclear whether they measurably alter the course of the disease. Hospitalization for fluid and electrolyte management and for supportive skin care is indicated for most patients.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, febrile, multisystem illness of unknown etiology that causes widespread vasculitis in young children. The incidence of KD peaks at about 9 to 11 months of age, with 80% of affected children being younger than 5 years.63 The diagnosis of KD disease can be made if and five of the following criteria are present65,66:

• Temperature higher than 39° C is present for more than 5 days

• Bilateral conjunctival injection: without exudates

• Erythema of the oropharynx or lips: with fissures or strawberry tongue

• Acute cervical lymphadenopathy

• Polymorphous erythematous exanthem: morbilliform, scarlatiniform, or maculopapular (may have plaques or target lesions)

• Edema of the palms and soles: with desquamation occurring 2 to 3 weeks after onset of the illness

Patients with only four of these symptoms meet the criteria if coronary aneurysms are found on echocardiography. The most important clinical complication is coronary artery aneurysms, which may lead to myocardial ischemia and sudden death.66,67 Other, less common complications include gallbladder hydrops, diarrhea, obstruction of the small bowel, arthritis, cystitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, valvulitis, and aseptic meningitis. All children with KD should be hospitalized. Management of KD is directed at reducing the risk for coronary artery aneurysm and thrombosis, which is achieved with high-dose aspirin and IVIG.65,67,68

Toxic Shock Syndrome

Staphylococcal TSS is a potentially lethal disease characterized by acute fever, generalized erythroderma, and hypotension. It is due to a localized infection or colonization with a toxin-producing strain of S. aureus.11 Although TSS is classically associated with menstruating girls using tampons, recent changes in the manufacturing and use of tampons have resulted in a decrease in the incidence of menstrual-associated TSS.69 Currently, the incidence of nonmenstrual TSS exceeds that of menstrual TSS.11,69 Symptoms characteristically begin with high fever, malaise, chills, headache, myalgia, vomiting, and diarrhea. Hypotension and multiorgan involvement follow rapidly. Cutaneous symptoms include a diffuse, blanching, macular eruption beginning on the trunk and spreading to the extremities. This is followed by desquamation, particularly on the palms and soles.61,63 The mucous membranes are involved, and erythema and ulceration of the pharyngeal, oral, conjunctival, or vaginal mucosa may occur. Complications include refractory shock, acute renal failure, neurologic symptoms, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and death.11,63 The diagnosis is usually made clinically. However, S. aureus may be isolated from a localized infection.69 Treatment of TSS includes hemodynamic stabilization of shock and management of multiorgan failure. Importantly, every attempt should be made to identify and treat the infection with local drainage, removal of infective material (tampon), and antistaphylococcal antibiotics.11,32,63

Treatment

Classic Exanthems and Viral Rashes

The vast majority of these illnesses require only supportive care and surveillance for complications. Treatment of fever and constitutional symptoms with ibuprofen or acetaminophen is helpful. Vitamin A has been shown to reduce risk for mortality and complication in children with measles.9 Treatment of scarlet fever is with penicillin.13 Care of patients with varicella should include attention to pruritus, wound care, and prevention of secondary infections.1,30 Immunocompromised children with varicella may benefit from acyclovir.32,33 Patients with hand-foot-and-mouth disease benefit from soothing anesthetic mouth rinses.15 All patients with viral illness must be kept away from pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals. All these illnesses have the potential for serious complications, and thus close monitoring for these adverse events is required.

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

The mainstay of treatment of impetigo is antibiotic therapy directed against Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Agents include cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, dicloxacillin, and oxacillin.33,37,39 Treatment of bacterial reservoirs with mupirocin may also be required. Erysipelas requires treatment with penicillin plus clindamycin. Tinea infections of the body, groin, and feet are treated with topical antifungal preparations (miconazole or clotrimazole) for 2 to 4 weeks.48 Tinea capitis is treated with 6 to 8 weeks of oral griseofulvin and selenium sulfide shampoo, with periodic surveillance of liver function tests.45,46 Molluscum infections may be left to resolve or, alternatively, treated by cryotherapy, excision, or application of chemicals.51,52 Because all these illnesses have the potential for serious complications, close monitoring for adverse events is required.

Pediatric Dermatitis

Treatment of atopic dermatitis is multidisciplinary in approach and includes behavior modification, emollients, topical steroids, and antihistamines. Diaper dermatitis is managed with measures aimed at decreasing regional irritation, including changes in diapering routine, use of barriers, and monitoring for candidal superinfection.56,57 Seborrheic dermatitis is treated with oatmeal baths and antiseborrheic shampoos. Ketoconazole is also effective.58

Severe Pediatric Rashes

HSP is usually a self-limited disease, and treatment is supportive. Relief of pain symptoms with NSAIDs is helpful.59 Meningococcemia is an overwhelming bacterial infection that requires ICU admission, early antibiotic therapy, fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support, and prophylaxis of close contacts. SSSS is also potentially life-threatening and mandates hospital admission, early antibiotic therapy, fluid and electrolyte management, and supportive skin care. All children with KD also require admission. Treatment with high-dose aspirin and IVIG is required, as well as surveillance for cardiovascular complications.65,67,68 Treatment of TSS entails ICU admission, hemodynamic stabilization, removal of infective source material, and early antibiotic therapy.23,32,63 All these illnesses have potentially devastating complications, and close and continual monitoring is therefore mandatory.

Follow-Up and Patient Education

Boguniewicz M. Atopic dermatitis: beyond the itch that rashes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:333–351.

Campbell M. Childhood rashes that present to the ED. Part I: viral and bacterial issues. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2007;4(3):1–24.

Campbell M. Childhood rashes that present to the ED. Part II: fungal, G. annulare, Kawasaki disease, insect related, and molluscum. Pediatr Emerg Med. 4(4), 2007.

Manders SM. Toxin-mediated streptococcal and staphylococcal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:383–398.

Pinna GS, Kafetzis DA, Tselkas OI, et al. Kawasaki disease: an overview. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:263–270.

Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral exanthems. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9(3):4.

1 Campell M. Childhood rashes that present to the ED. Part 1: viral and bacterial issues. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2007;4(3). Emedicine.net.

2 Hogan PA. Viral exanthems in childhood. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37(Suppl 1):S15–S16.

3 Anders JF, Jacobson RM, Poland GA, et al. Secondary failure rates of measles vaccines: a metaanalysis of published studies. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:62–66.

4 Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Rivetti A, et al. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2005. CD004407

5 Semba RD, Bloem MW. Measles database. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:243–255.

6 Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl 1):S4–16.

7 Sabella D. Measles: not just a childhood rash. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:207–213.

8 Ratnam S, Tipples G, Head C, et al. Performance of indirect immunoglobulin M (IgM) serology tests and IgM capture assays for laboratory diagnosis of measles. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:99–104.

9 Yang HM, Mao M, Wan C. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2005. CD001479

10 Schneider-Schaulies J, Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Measles infection of the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:247–252.

11 Manders SM. Toxin-mediated streptococcal and staphylococcal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;29:383–398.

12 Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:470–511.

13 Lamden KH. An outbreak of scarlet fever. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:394–397.

14 Guven A. Hepatitis and hematuria in scarlet fever. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:985–986.

15 Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral exanthems. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9(3):4.

16 Weir E, Sider D. A refresher on rubella. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:1680–1681.

17 Plotkin SA. The history of rubella and rubella vaccination leading to elimination. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:S164–S168.

18 Moore TL. Parvovirus-associated arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:289–294.

19 Ferraz C, Cunha F, Mota T, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in a child with human parvovirus B19 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:1009–1010.

20 Kellermayer R, Faden H, Grossi M. Clinical presentation of parvovirus B19 infection in children with aplastic crisis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1100–1101.

21 Rao SP, Desai N, Miller ST. B19 parvovirus infection and transient aplastic crisis in a child with sickle cell anemia: concomitant bone marrow/bone infarction and acute chest syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18:175–177.

22 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Enterovirus surveillance—United States, 2002-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(6):153–156.

23 Lyall EGH. Human herpesvirus 6: primary infection and the central nervous system. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:693–696.

24 Koch WC. Fifth (human parvovirus) and sixth (herpesvirus 6) diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:343–356.

25 Braun DK, Dominguez G, Pellett PE. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:521–567.

26 Dockrell DH. Human herpesvirus 6: molecular biology and clinical features. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:5–18.

27 Drago F, Rebora A. The new herpesviruses: emerging pathogens of dermatological interest. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:71–75.

28 Shapiro ED, Vazquez M, Esposito D, et al. Effective of 2 doses of varicella vaccine in children. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:312–315.

29 Gershon AA, Gershon MD, Breuer J, et al. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:S2–S7.

30 Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet. 2007;369:1365–1376.

31 Daley AJ, Thorpe S, Garland SM. Varicella and the pregnant woman: prevention and management. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:26–33.

32 Chapel KL, Rasmussen JE. Pediatric dermatology: advances in therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:513–526.

33 Klassen TP, Harling L. Acyclovir for treating varicella in otherwise healthy children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2005. CD002980

34 Seward JF. Update on varicella. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:619–621.

35 Gnann JW. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:S91–S98.

36 Kushner D, Caldwell BD. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1996;86:257–259.

37 George A, Rubin G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of treatments for impetigo. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:480–487.

38 Steer AC, Danchin MH, Carapetis JR. Group A streptococcal infections in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43:202–213.

39 Brown J, Shriner DL, Schwartz RA, et al. Impetigo: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:251–255.

40 Feaster T, Singer JI. Topical therapies for impetigo. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26:222–231.

41 Odell CA. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) skin infections. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:273–277.

42 Kilburn SA, Featherstone P, Higgins B, et al. Interventions for cellulitis and erysipelas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (6):2010. CD004299

43 Krasagakis K, Valachis A, Maniatakis P, et al. Analysis of epidemiology, clinical features and management of erysipelas. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1012–1017.

44 Lazzarini L, Conti E, Tositti G, et al. Erysipelas and cellulitis: clinical and microbiological spectrum in an Italian tertiary care hospital. J Infect. 2005;51:383–389.

45 Andrews MD, Burns M. Common tinea infections in children. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:1415–1420.

46 Chan YC, Friedlander SF. New treatments for tinea capitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:97–103.

47 Chen BK, Friedlander SF. Tinea capitis update: a continuing conflict with an old adversary. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:331–335.

48 Huang DB, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Wu JJ, et al. Therapy of common superficial fungal infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:517–522.

49 Ali S, Graham TAD, Forgie SED. The assessment and management of tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:662–668.

50 Braue A, Ross G, Varigos G, et al. Epidemiology and impact of childhood molluscum contagiosum: a case series and critical review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:287–294.

51 Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93–99.

52 Van der Wouden JC, Koning S, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, et al. Interventions for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2006. CD004767

53 Boguniewicz M. Atopic dermatitis: beyond the itch that rashes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:333–351.

54 Adam R. Skin care of the diaper area. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:427–433.

55 Prasad HR, Srivastava P, Verma KK. Diaper dermatitis—an overview. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:635–637.

56 Scheinfeld N. Diaper dermatitis: a review and brief survey of eruptions of the diaper area. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:273–281.

57 Atherton DJ. A review of the pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of irritant diaper dermatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:645–649.

58 Schwartz RA, Janusz CA, Janniger CK. Seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:125–132.

59 Lim DC. Could it be Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Aust Fam Physician. 2009;39:321–324.

60 Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:395–409.

61 Freiman A, Borsuk D, Sasseville D. Dermatologic emergencies. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173:1317–1319.

62 Herf C, Nichols J, Fruh S, et al. Meningococcal disease: recognition, treatment, and prevention. Nurse Pract. 1998;23(8):30–40.

63 Campell M. Childhood rashes that present to the ED. Part 2: fungal, G annulare, Kawasaki disease, insect related, and molluscum. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2007;4(4). Emedicine.net.

64 Milonovich LM. Meningococcemia: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21:75–80.

65 Nasr I, Tometzki AJP, Schofield OMV. Kawasaki disease: an update. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:6–12.

66 Pinna GS, Kafetzis DA, Tselkas OI, et al. Kawasaki disease: an overview. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:263–270.

67 Oates-Whitehead RM, Baumer JH, Haines L, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst. (4):2003. CD004000

68 Sato N, Sugimura T, Akagi T, et al. Selective high dose gamma globulin treatment in Kawasaki disease: assessment of clinical aspects and cost effectiveness. Pediatr Int. 1999;41(1):1–7.

69 Andrews MM, Parent EM, Barry M, et al. Recurrent nonmenstrual toxic shock syndrome: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1470–1479.