Chapter 1 Applied Anatomy

General Considerations

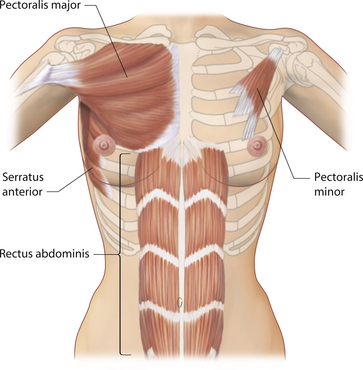

When considering the anatomy of the breast as it relates to aesthetic breast surgery, it is helpful to distinguish between physiologic anatomy and structural anatomy. Physiologic anatomy relates to the arterial and venous supply, innervation and lymphatic drainage of the breast. Essentially, these are the anatomical features of the breast which must be respected and manipulated appropriately during the various types of aesthetic procedures described in this book. For instance, failure to adequately preserve arterial inflow to the nipple–areola complex (NAC) during a redo augmentation mastopexy can result in disastrous consequences with potential loss of this very important structure. For this reason, it is imperative that the informed aesthetic surgeon fully understand the various sources of innervation and vascular supply to the breast. Structural anatomy is inherently much more interesting. The support structure of the breast includes the parenchyma, fat, skin and, most importantly, the fascial architecture of the breast. When it comes to surgically manipulating the breast, understanding how these variables interrelate to one another can profoundly affect the quality and success of the overall result. Included in the structural anatomy of the breast is the underlying musculature. Although not part of the breast, the location and attachments of the pectoralis major and minor muscles and, to a lesser extent, the serratus anterior and the rectus abdominis can all affect the final result after aesthetic breast surgery as a result of the common practice of placing implants under these muscles. Understanding where these muscles are located in relation to the overlying breast can greatly facilitate their use and avoid implant malposition.

Embryology

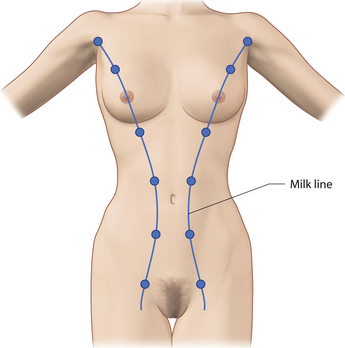

The breast develops initially as a ventral ectodermal thickening along the so-called ‘milk line’ in mammals (Figure 1.1). Through a process of regression and maturation, discrete collections of nascent breast progenitor cells collect at specific sites along this milk line. This line extends from the axilla all the way down to the groin. Occasionally full regression fails to occur and ectopic breast formation outside of the usual location at the fourth intercostal space can develop anywhere along this line. Most commonly this is represented as an accessory nipple located at the left inframammary fold (Figure 1.2 A,B). Occasionally, a surprisingly well-formed rudimentary areola can form in association with the ectopic nipple (Figure 1.2 C). Also, it is not unusual for some women to undergo actual accessory breast parenchymal development. This usually occurs in the axilla, either unilaterally or bilaterally, and may or may not be associated with an overlying nipple or areola rudiment. This tissue can actually enlarge during pregnancy to the point where surgical excision is desired once the post-gestational period is reached (Figure 1.3 A–D). Typically, however, the breast bud located at the fourth intercostal space eventually develops on each side into the mature breast. Development starts with the onset of puberty, usually around the age of 11 or 12, and variably continues through the teenage years. Generally speaking, initial primary breast growth is completed by the age of 18 to 20. Subsequent secondary changes in the size and shape of the breast then continue under the influence of a wide variety of causes including pregnancy, weight gain or loss, hormonal changes, aging and breast-feeding. The net result is that the breast undergoes an evolution of change in appearance over the life of a woman. It is important for the aesthetic surgeon to understand this evolution when surgical alterations in breast size or shape are considered. Certainly, how the breast looks today may not necessarily be how the breast looks in ten years. Understanding and, when possible, predicting these changes can greatly improve the results of aesthetic breast surgery.

Arterial Anatomy

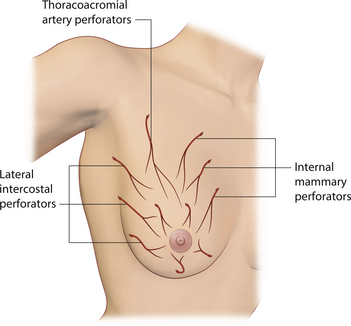

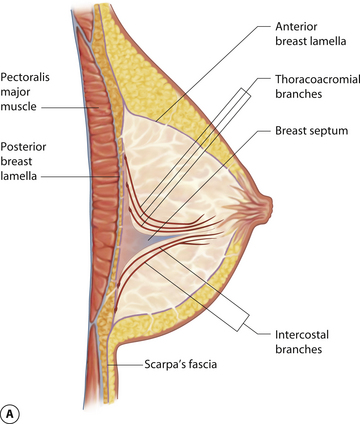

Understanding of the arterial anatomy of the breast is enhanced when it is realized that this anatomy is in place and fixed before the breast even begins to develop. Essentially, it is the vascular anatomy of the chest wall. Then, as the breast begins to enlarge, the available arterial and venous supply simply grows with the breast. As a result, the blood supply of the breast is diffuse and comes from a variety of potential sources including the internal thoracic artery via large anteriorly located intercostal perforators, the lateral thoracic artery, branches from the thoracoacromial axis through perforators running through the pectoralis major muscle, and anterior and posterior branches from the intercostal arteries, particularly branches from the 5th and 6th intercostal spaces (Figure 1.4). As a result, the breast can be accessed through many different incisions using a host of variably oriented pedicles and still have blood supply to the NAC preserved. Despite this diffuse blood supply, it is helpful to note that the dominant blood supply to the breast comes from the internal mammary system. These perforators off the internal mammary have an impressive pressure head due to their proximity to the heart, as anyone who has done a free flap anastomosis to the internal mammary can attest. Also, the internal mammary perforators interconnect with all other vascular sources to the breast. For this reason, throughout this book, many of the described procedures will preserve the internal mammary perforators whenever possible. The versatility these vessels provide allows division of all other vascular sources without risk of tissue necrosis.

Innervation

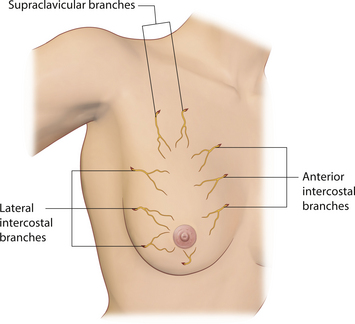

In keeping with the tone set by the vascular supply to the breast, the innervation of the breast is also diffuse and variable. Multiple nerve branches from the lateral and anterior cutaneous branches of the 2nd through 6th intercostal nerves as well as the supraclavicular nerves enter and ramify within the breast (Figure 1.5). As for the all-important innervation to the NAC, the anterior and lateral branches of the intercostal nerves and, in particular, the lateral branch of the 4th intercostal nerve tend to ramify predominantly to the subareolar plexus, although lesser and variable contributions from other surrounding intercostal nerves also ramify to the area. Generally speaking, the contributions of the lateral branches are more significant than the smaller anterior branches. The location of the nerves within the breast varies as well. After passing through the intercostal spaces, the nerves ramify within the breast, sometimes passing along the deep fascia, sometimes passing superficially through the substance of the breast. Clearly, many of the various pedicle procedures for mastopexy and breast reduction will inevitably disrupt some nerve fibers. In addition, creating a pocket under the breast for the placement of an implant will also sever some nerve fibers. If possible, every effort should be made to avoid injury to the main anterior and lateral nerve branches as they pass through the intercostal spaces anteriorly and laterally and enter the breast. Once in the breast, inevitable severing of nerve fibers must be accepted as a consequence of surgically altering the breast.

Fascial Support Structure

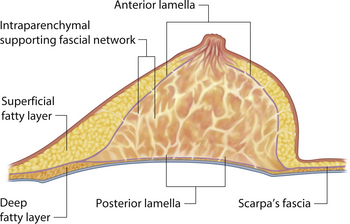

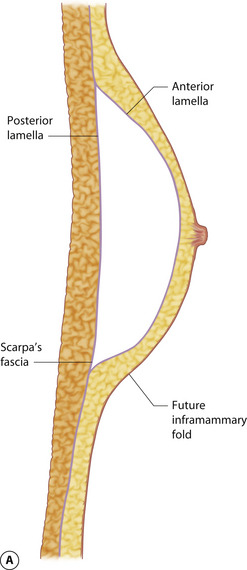

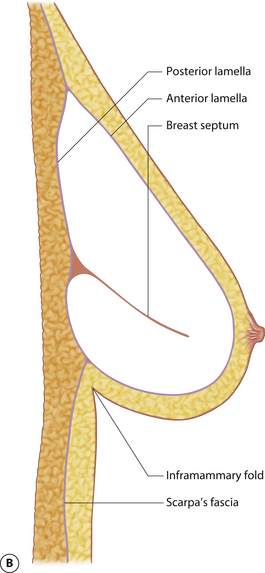

The mature breast demonstrates both a superficial and a deep fascial support system. Essentially, the breast bud develops within Scarpa’s fascia as it extends up onto the chest wall and the fascia splits to form an anterior and posterior lamella. Anteriorly, this lamella serves as a dissection plane for many surgeons when performing a mastectomy. The posterior lamella separates the breast from the underlying pectoralis major muscle and serves as the plane of dissection for subglandular breast augmentation. Within the breast, between these two lamellae lie interdigitating connective tissue fibers extending throughout the breast (Cooper’s liga-ments), which contribute to the general support and shape of the breast (Figure 1.6).

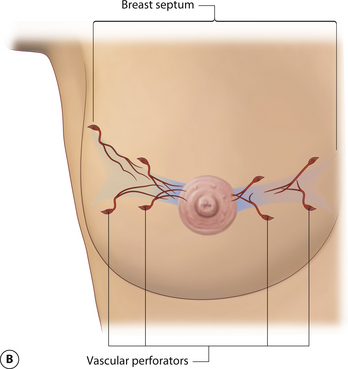

While the interdigitating fascial network is diffusely distributed, there is a well-documented and distinct fascial septum that is oriented horizontally across the breast at approximately the level of the 5th rib. This septum roughly separates the breast into a superior two-thirds and an inferior one-third. The septum takes origin from the pectoral fascia and is associated with a well-defined vascular arcade which extends with the septum up to the NAC. On the cranial side of this septum lies a vascular network which takes origin from perforating branches of the thoracoacromial artery and a branch of the lateral thoracic artery. On the caudal side are perforating branches from the intercostal arteries. The varied and diffuse nerve supply to the breast also courses, at least partly, within this septum. As such, this fascial condensation forms a connective tissue mesentery along which passes an important source of neurovascular support to the breast and, in particular, the NAC (Figure 1.7). This septum was first described as an independent entity by Wuringer and colleagues and, in my view, their contribution remains as one of the most important tools yet described to allow meaningful understanding of the intraparenchymal vascular and structural anatomy of the breast. This septum is so distinct that Wuringer has been able to describe a breast reduction technique that bases the blood supply to the NAC on this intraparenchymal vascular mesentery. Although uniformly present in breasts with any degree of hypertrophy, the septum and its associated mesentery tend to be more distinct in thinner patients who exhibit more of a fibrous nature to their breast (Figure 1.8). In breasts with a greater fat content, and particularly in the obese, the septum becomes less readily identifiable. However, the principles of pedicle management that the presence of this septum mandates do not change, no matter how distinct it is. For instance, when using an inferior pedicle technique to preserve the blood supply to the NAC, it becomes quite counterproductive to undermine the pedicle to such an extent that the caudal vascular sheet coming up into the pedicle becomes disrupted. The blood supply to the NAC at that point becomes based on dermal collateral flow, which can be less vigorous than the direct axial flow provided by the intercostal perforators running within the septal mesentery. Of course, as the length of the pedicle increases in larger breast reductions, preserving this vascular arcade becomes more critical in ensuring a viable NAC postoperatively. Although subtle, once I personally became aware of this anatomic relationship, I was able to locate it and respect the vascular pattern contained within the mesentery in every patient. It is interesting to postulate what effect inadvertent division of this breast septum may have had on previously reported instances of NAC ischemia after inferior pedicle breast reduction.

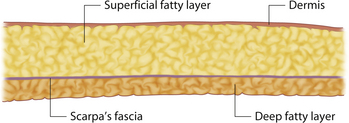

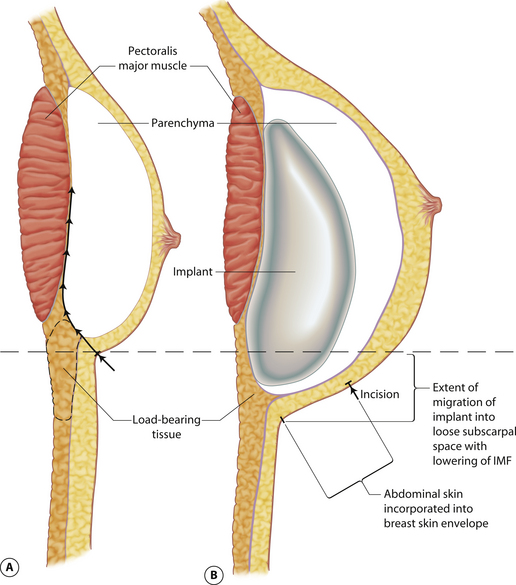

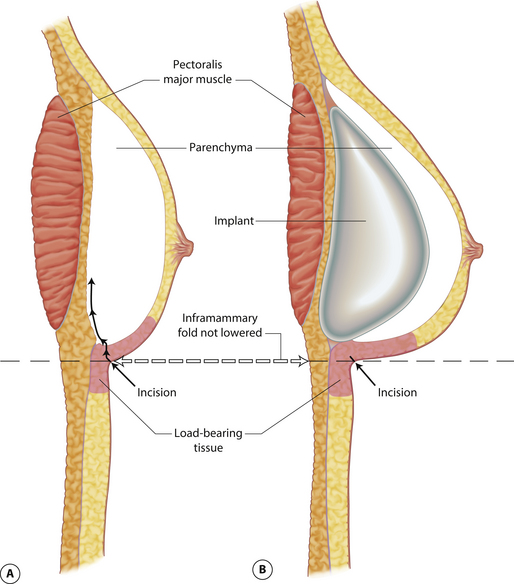

Understanding and identifying the subtle anatomical relationships noted at the level of the inframammary fold between the breast, Scarpa’s fascia and the anterior and posterior lamellae is of infinite importance in successful aesthetic breast surgery as a stable and properly positioned inframammary fold is the foundation upon which all other breast manipulations are based. For this reason, it is important to manipulate this anatomy to optimal advantage. The superficial fat of the anterior abdominal wall is divided into two distinct fatty layers. The superficial layer of fat is thicker, dense and more compact than the thinner and more areolar deeper layer. These two fatty layers are separated by a well-defined fascial condensation called Scarpa’s fascia (Figure 1.9). Along the inferior pole of the breast, Scarpa’s fascia inserts into the lamellar framework of the breast where the anterior and posterior lamellae fuse. As the enlarging breast develops, the mass effect of the tissue located just superior to this fusion point folds over itself inferiorly to passively form the inframammary fold (Figure 1.10 A,B). When incisions are made in the inframammary fold during breast augmentation, there is a tendency to incise through Scarpa’s fascia thus exposing the two fatty layers to forces from above in the form of the implant. Because the deep layer of fat is areolar and easily stretches open under the influence of any kind of force, any operative technique that opens this layer surgically can have the ultimate effect of inadvertently lowering the fold to a point lower than was initially planned as the weight of the overlying implant forces the loose subscarpal space open over time. In essence, abdominal skin below the planned incision is incorporated into the new breast skin envelope. This unplanned expansion of the lower pole of the breast and the resulting inferior implant malposition can have a decidedly negative impact on the shape of the resulting breast (Figures 1.11, 1.12 A,B). Alternatively, accessing the underside of the breast on top of Scarpa’s fascia protects the subscarpal space from potentially deforming pressure from above and, instead, any forces exerted by either implants or parenchyma are realized by the firmer and more compact superficial layer of fat, which is much less likely to give way. In this fashion, the location of the inframammary fold can be surgically positioned with greater confidence (Figures 1.13, 1.14 A,B). Incision strategies and fold management will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters.

Parenchyma and Fat

The breast parenchyma and associated fat make up the bulk of the volume of the breast. The proportion that each contributes to this volume is subject to tremendous variability, not only between patients but also within the same patient, depending on any of the many variables which can effect the breast including age, weight, pregnancy, hormonal changes and genetics. Breasts that are particularly fibrous can be more difficult to sculpt surgically than predominantly fatty breasts. Also, not all fat is the same, as some patients have a blocky, firm consistency to their fat while others have a very loose and elastic texture to the fat. Preoperatively predicting what type of fat a patient has may impact what types of surgical maneuvers may be required to shape the breast appropriately, particularly in cases of mastopexy and reduction. For instance, patients with a firm, blocky fat will require greater precision in flap and pedicle development as their tissue will not mold together and conform as easily as a patient who has a looser and more elastic type of fat. Conversely, a patient with firmer fat may not need internal shaping sutures while the patient with a more elastic fatty consistency will often require internal parenchymal support to achieve the optimal result.

Skin

The skin of the breast can play a vital role in the outcome of any aesthetic breast procedure. As with other structures within the breast, the character of the skin of the breast can vary dramatically from patient to patient. In youth, the skin of the breast often has a compact consistency, exhibits excellent rebound when stress is applied to it and, generally, provides firm support to the underlying parenchyma and fat, which contributes greatly to the uplifted appearance of the youthful breast. Then, as a result of many influences including genetic factors, advancing age, weight gain and pregnancy, the dynamics of the skin of the breast change. As the underlying breast enlarges, the overlying skin becomes thinned particularly around the NAC, loses its ability to rebound and cannot support the volume of the breast as before. With increasing size, stretch marks can develop and the breast becomes variably ptotic with loss of shape. Either due to an inferior location initially or due to fluctuations in the filling out of the skin envelope, the location of the NAC can appear low in relation to the breast mound. Perhaps more importantly, after surgical alteration of the breast, the tendency for the breast skin to stretch seems to increase in many patients. This observation is easy to understand in light of the fact that during many aesthetic breast procedures the internal support structure of the breast is variably released. When this is coupled with any procedure which increases the volume of the breast, as in breast augmentation, it is understandable that the breast skin could stretch. Properly assessing the quality of the breast skin as well as the surface area of the skin envelope in relation to the underlying volume becomes quite important when designing a surgical strategy to iprove the aesthetics of the breast. Accurately judging how the skin will react to an underlying force such as a breast implant or repositioned breast parenchyma can greatly impact the long-term aesthetic result. Generally speaking, any aesthetic procedure which places undue reliance on the skin envelope of the breast to provide shape will eventually fail. It is far more reliable to provide a stable inner breast support structure and then allow the skin to simply redrape around the surgically created mound.

Muscles

From an aesthetic standpoint, the muscles of the chest wall are important in breast surgery for two reasons. First, perforators from the main feeding vessels of the chest wall travel through the muscles to supply the breast. Therefore, for instance, the pectoralis major serves as a conduit for many perforators to enter the breast from the thoracoacromial system. Secondly and perhaps more importantly, breast implants are commonly placed under these chest wall muscles. Therefore, the location of these muscles in relation to the overlying breast becomes very important in determining the shape of the surgically altered breast (Figure 1.15). Although several chest wall muscles support the upper torso, the muscle which impacts most directly on the breast is the pectoralis major. This muscle takes origin from a wide attachment along the inner sternal area and this origin extends from the medial clavicle, down along the entire lateral sternal border and then variably onto the lower medial cartilages of ribs 6 and 7. Occasionally, the origin can extend down to the rectus abdominus fascia and the upper fibers of the external oblique muscle. Additionally, there are accessory fibers of origin which extend from the underside of the muscle and connect to the anterior bony surfaces of ribs 4 through 6. Vascular perforators from the intercostal system often accompany these accessory muscle origins. As a result, a wide area of origin for the pectoralis major is present and this area can cover as much as the medial fourth of the overlying breast contour. Recognizing this wide area of origin is very important when making a subpectoral pocket for breast augmentation and this anatomy will be discussed further in subsequent chapters. From this wide area of origin, the fibers converge into a thick tendon which inserts in a spiral fashion into the intertubercular groove of the humerus.