Appendicitis

Anatomy of the appendix

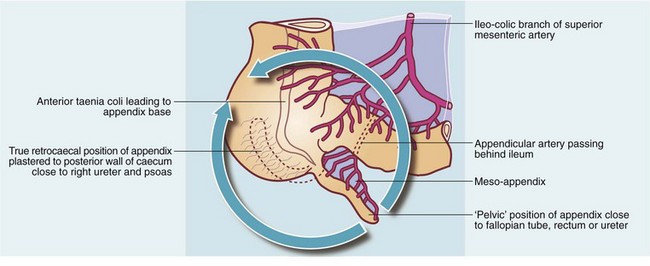

The appendix is a blind-ending tube arising from the caecum at the meeting point of the three taeniae coli, just distal to the ileo-caecal junction. The appendix base thus lies in the right iliac fossa, close to McBurney’s point. This is two-thirds of the way along a line from umbilicus to anterior superior iliac spine (see below, Fig. 26.6, p. 348). In most cases, the appendix is mobile within the peritoneal cavity, suspended by its mesentery (meso-appendix), with the appendicular artery in its free edge. This is effectively an end-artery, with anastomotic connections only proximally.

The appendix is described as lying in several ‘classic’ sites, but apart from the true retrocaecal appendix, the organ probably floats in a broad arc about its base (see Fig. 26.1). Only inflammation will fix it in a particular place. Its position then determines the clinical presentation. In about 30% of appendicectomies, it lies over the pelvic brim the (‘pelvic appendix’). In some cases, the appendix lies retroperitoneally behind the caecum and often plastered to it by fibrous bands. Thus, an inflamed retrocaecal appendix may irritate the right ureter and psoas muscle, and may even lie high enough to simulate gall bladder pain.

Pathophysiology of appendicitis

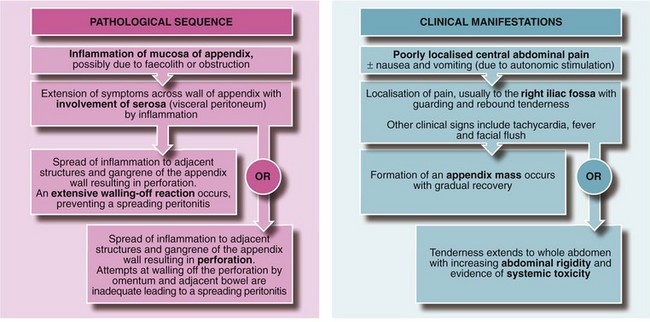

By this stage the necrotic glandular mucosa sloughs into the lumen, which becomes distended with pus. Finally, the end-arteries supplying the appendix thrombose and the infarcted appendix becomes necrotic or gangrenous at the distal end and the appendix begins to disintegrate. Perforation soon follows and faecally contaminated contents spread into the peritoneum. If the spilled contents are enveloped by omentum or adherent small bowel, a localised abscess results; otherwise spreading peritonitis develops. Acute appendicitis is illustrated histologically in Figure 26.2.

Clinical features of appendicitis

The pathophysiological evolution of appendicitis and corresponding symptoms and signs are illustrated in Figure 26.3.

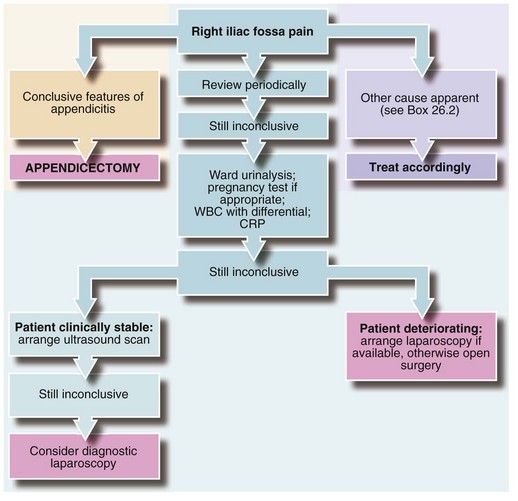

Making the diagnosis of appendicitis

Diagnosis of acute appendicitis poses little difficulty if the patient exhibits the classic symptoms and signs summarised in Box 26.1. However, the patient may present at a very early stage, or the signs may have some other pathological cause. At least two out of three children admitted to hospital with suspected appendicitis do not have the condition.

Differential diagnosis

This theoretically includes all the causes of an acute abdomen. However, the conditions of practical importance are summarised in Box 26.2. These other conditions rarely need operation. Certain uncommon conditions such as Yersinia ileitis and inflamed Meckel’s diverticulum (Fig. 26.4) are included in the list but they can only be distinguished from appendicitis at laparoscopy or operation.

The equivocal diagnosis

Various scoring systems have been devised to improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis. The best known is the Alvarado score (see Table 26.1) but results are too variable for it to be of much clinical benefit.

Table 26.1

Scoring system for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis based on the Alvarado score

| Feature | Score |

| Migration of pain from central abdomen to right iliac fossa | 1 |

| Anorexia | 1 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 1 |

| Tenderness in right iliac fossa | 2 |

| Rebound tenderness | 1 |

| Raised temperature (≥37.5°C) | 1 |

| Raised leucocyte count ≥10 × 109/L | 2 |

| Neutrophilia of ≥75% | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

Appendicectomy

Antibiotic prophylaxis

In appendicitis, most intra-abdominal infective complications and wound infections occur in perforated or gangrenous appendicitis (see Box 26.3). Most infecting organisms are anaerobic and infections can largely be prevented by prophylactic metronidazole. Rectal suppositories are as effective as intravenous metronidazole and are cheaper but are best given 2 hours before operation. Aerobic organisms are involved in fewer cases and some surgeons advocate additional prophylaxis with an antibiotic such as a cephalosporin. In adults with moderate appendicitis, trials of antibiotic treatment alone compare favourably with appendicectomy but about a quarter present later with recurrent appendicitis.

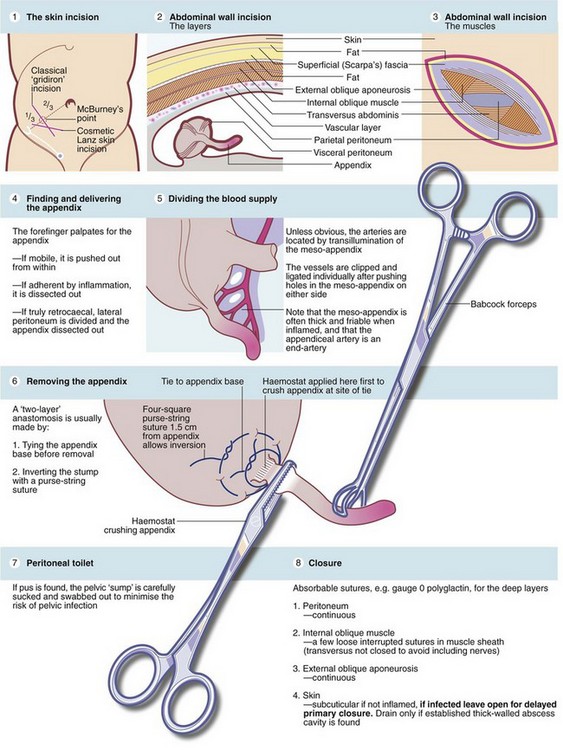

Technique of appendicectomy

The principal steps are illustrated in Figure 26.6 and should be understood by any doctor assisting with the operation. Increasingly, laparotomy is being replaced by laparoscopic diagnosis and surgery, but the principles are similar. Surgeons performing appendicectomy need to be aware of possible appendiceal neoplasms, present in 0.5—0.9% of appendectomies. Most are innocent carcinoid-type tumours but others are mucinous adenocarcinomas.

The ‘lily-white’ appendix

• Mesenteric lymph nodes in children may be grossly enlarged by mesenteric adenitis—probably viral in origin

• The terminal ileum may be thickened and reddened by Crohn’s disease or, more rarely, by Yersinia ileitis. The latter is a self-limiting condition caused by the organism Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and requires no specific treatment. The appendix is removed but the bowel left untouched. If possible, an enlarged mesenteric node is removed for histological examination

• A Meckel’s diverticulum may be found within 60 cm of the ileocaecal valve—if inflamed, this is removed but a wide-mouthed non-inflamed diverticulum is usually left alone

• Both ovaries can usually be palpated—ovaries may be twisted, inflamed or enlarged or an inflamed Fallopian tube may be seen

• Cholecystitis, sigmoid diverticulitis (with the sigmoid displaced to the right), inflammation of a caecal diverticulum, hydronephrosis or a leaking aneurysm are rarely found