39 Appendicitis

• Appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the United States.

• Physical signs and symptoms vary with the location of the appendix.

• Children, pregnant women, and elderly patients may exhibit subtle clinical findings.

• No single diagnostic test can reliably confirm or exclude appendicitis.

• Early surgical consultation should not be delayed for diagnostic testing.

• Protocols involving ultrasound and then computed tomography can decrease radiation exposure in patients requiring diagnostic imaging.

• Narcotic analgesia does not interfere with diagnostic accuracy.

• Prophylactic antibiotic therapy, properly timed, decreases postoperative infection rates.

Epidemiology

About 1% of patients seeking care in the ED for abdominal pain have appendicitis, and missed diagnosis and subsequent morbidity continue to occur. The lifetime risk for appendicitis is approximately 9% in men and 7% in women.1 The classic “textbook” manifestation of appendicitis—right lower quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity, and migration of pain from the periumbilical area to the right lower quadrant—is the exception rather than the norm. Symptoms are frequently atypical, and subtle findings are common. Delayed diagnosis results in a higher risk for perforation, which increases morbidity and mortality. When the diagnosis is delayed, about 20% of appendicitis cases perforate.

Anatomy

The appendix is a tubular structure that arises from the cecum and consists primarily of smooth muscle and an abundance of lymphoid tissue. The average adult appendix can reach a length of 10 cm with a luminal width of 6 to 7 mm. Innervation from sympathetic and vagus nerves accounts for referred pain to the umbilicus when inflammatory changes are present. The location of the appendix (retrocecal, 65%; pelvic, 31%; subcecal, 2%) determines the clinical findings and risk for the development of perforated appendicitis.2

Pathophysiology

Acute appendicitis develops as a result of luminal obstruction, which promotes bacterial overgrowth and distention. Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen is commonly caused by fecal stasis and fecaliths; other obstructive masses include lymphoid hyperplasia, vegetable matter, fruit seeds, intestinal worms, inspissated radiographic barium, and tumors (e.g., carcinoid). Luminal obstruction creates a closed space in which bacterial overgrowth leads to the accumulation of fluid and gas. Organisms are typically polymicrobial, with a predominance of anaerobic and gram-negative species.2

Clinical Presentations

Classic

Up to 50% of patients have a normal body temperature on initial arrival at the ED.3 Patients with significant inflammation prefer to remain still in an effort to minimize peritoneal irritation. The right leg may be flexed at the hip to further decrease peritoneal stretch (see Table 39.1, Special Maneuvers That Suggest Appendicitis, online at www.expert.consult.com). Palpation of the abdomen generally reveals localized right lower quadrant tenderness. Rebound tenderness, voluntary and involuntary guarding, and rigidity may be observed, depending on the extent of appendiceal inflammation.

| Rovsing sign | With the patient in the supine position, palpation of the left lower quadrant causes pain in the right lower quadrant. |

| Psoas sign | With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, extension of the right hip increases pain in the right lower quadrant (when an inflamed appendix is overlying the right psoas muscle). |

| Obturator sign | With the patient in the supine position, internal rotation of a passively flexed right hip and knee increases right lower quadrant pain. |

Physical signs and symptoms vary with the location of the appendix. If the appendix is retrocecal, pain and tenderness may localize to the flank and not to the right lower quadrant. A retroileal appendix in men or boys may irritate the ureter with resulting radiation of pain to the testicle. The gravid uterus of a pregnant patient was previously thought to displace the appendix superiorly as the pregnancy progresses and cause right upper quadrant or flank pain. However, recent studies suggest that this conventional belief may be incorrect and that the location of the appendix may be similar in pregnant and nonpregnant patients.4,5 A pelvic appendix may irritate the bladder or rectum and result in dysuria, suprapubic pain, or a more pronounced urge to defecate. If the appendix is low lying, isolated rectal tenderness may be the only sign.2

Variations

Children

Children with appendicitis commonly exhibit fever and vomiting. These two signs, along with abdominal distention, are most often seen in infants. A lethargic, irritable baby with grunting respirations may be a typical manifestation in this age group. Toddlers are more likely to have vomiting and fever followed by pain. In school-age children, vomiting and abdominal pain are the more frequent symptoms.6 When the diagnosis is unclear, one should avoid diagnosing acute gastroenteritis in young children without diarrhea.

In the vast majority of children, the diagnosis of appendicitis is made only after perforation occurs, possibly because of a child’s inability to describe the pain or the physician’s misattribution of symptoms to other childhood diseases or to gastroenteritis. As a result of perforation, worsening peritonitis in children might be manifested as lethargy, inactivity, and hypothermia.7

Adolescent girls are a subset of the pediatric population that deserves special attention in the evaluation of acute appendicitis. The etiology of right lower quadrant pain in prepubertal and postpubertal girls includes ovarian torsion, ovarian cyst, intrauterine pregnancy, and ectopic pregnancy. A urine pregnancy test followed by pelvic ultrasonography may be helpful in distinguishing ovarian pathology from appendicitis.6

Elderly

Elderly patients are often initially seen late in the course of the disease and are three times more likely than the general population to have perforated appendicitis. The elderly have a higher incidence of early perforation (up to 70%) because of the anatomic changes in the appendix that occur with age, such as thinner mucosal lining, decreased lymphoid tissue, a narrowed appendiceal lumen, and atherosclerosis.8 A definitive diagnosis is often difficult to make because of associated comorbid conditions and the possibility of immunosuppression. Appendicitis accounts for 7% of abdominal pain in the elderly. Geriatric patients most commonly have an atypical manifestation and delay seeking medical intervention.9 In patients older than 70 years, the mortality rate is higher than 20% because of diagnostic and therapeutic delays.10 The majority of older patients with acute appendicitis are afebrile and do not have leukocytosis. When the clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings are equivocal, a low threshold for surgical consultation and inpatient observation must be considered for elderly patients with abdominal pain.

Pregnant Women

Pregnancy appears to have a protective effect on the development of appendicitis, especially in the third trimester.2 A fetal loss rate of up to 5% is seen in patients with unruptured appendicitis. Maternal death from appendicitis is extremely rare; however, perforation and subsequent peritonitis cause fetal mortality to rise to 30% and maternal mortality to 2%. The use of ultrasonography may differentiate obstetric causes of abdominal pain from appendicitis without the need for imaging studies that involve radiation, such as computed tomography (CT). Once the diagnosis of appendicitis has been made in a pregnant patient, urgent surgical exploration should be performed.11

Differential Diagnosis

When a patient complains of abdominal pain, suspicion for appendicitis, whether high or low, should be present in the clinician’s thought. The differential diagnosis for acute appendicitis is extensive and includes all causes of an acute abdomen (Box 39.1). Given that atypical manifestations in children, pregnant women, and the elderly are not uncommon, a high index of suspicion and early surgical consultation are critical.12

Diagnostic Testing

No single diagnostic test can reliably confirm or exclude the diagnosis of appendicitis. Diagnostic testing should not delay surgical consultation for patients with worrisome findings on examination. The surgeon should be engaged immediately (before laboratory testing or imaging) for a patient with an acute abdomen or when appendicitis is the most likely clinical diagnosis (Box 39.2).

Box 39.2 Diagnostic Considerations

Laboratory Testing

Elevations in the white blood cell (WBC) count, percentage of bands, absolute neutrophil count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level have each been associated with a greater likelihood of appendicitis. Taken individually, these tests have poor predictive value.7 In combination, elevated WBC and CRP values have been associated with positive likelihood ratios between 7 and 23 for the prediction of appendicitis in both children and adults.13,14 The likelihood of appendicitis when both WBC and CRP values are in the normal range is low.15,16 However, CRP and WBC values vary with age and the duration of symptoms; patients who are seen early in the disease process may have a normal CRP level.

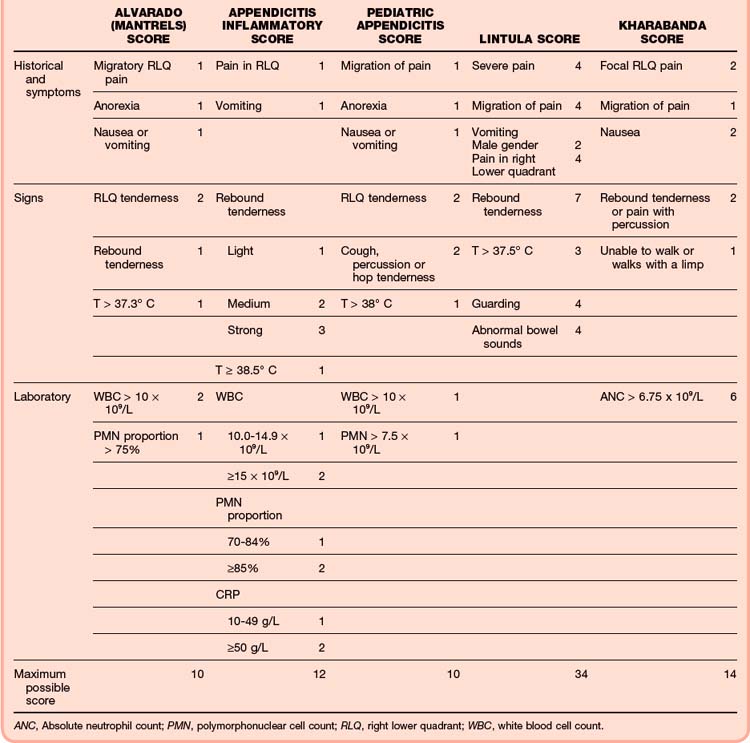

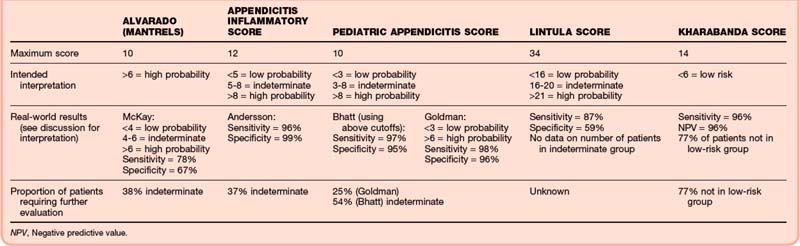

Scoring systems that include historical data, physical findings, and laboratory markers have been developed to assist in differentiating appendicitis from other sources of abdominal pain. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these systems are not sufficient to predict the presence or absence of appendicitis with adequate reliability. These tools are more frequently used to risk-stratify patients who may need further diagnostic testing or observation.17–21

![]() See additional information on this topic, Table 39.2, Common Appendicitis Scoring Systems, and Table 39.3, Interpretation of Common Appendicitis Scoring Systems, online at www.expertconsult.com.

See additional information on this topic, Table 39.2, Common Appendicitis Scoring Systems, and Table 39.3, Interpretation of Common Appendicitis Scoring Systems, online at www.expertconsult.com.

Appendicitis Scoring Systems

Table 39.2 presents some common appendicitis scoring systems.51–53 Table 39.3 presents cutoff values, sensitivities and specificities, and size of the indeterminate group for these same scoring systems.51–57 Please note that the scoring systems have been applied in many more settings than can reasonably be presented here and that the accuracy of the scoring systems may vary significantly by study. In particular, the Alvarado score, developed in 1986, has been studied extensively.

An abnormal urinalysis result must be interpreted with caution in a patient with suspected appendicitis and a low likelihood of cystitis. Abnormal urinalysis results (including more than 4 red blood cells [RBCs] per high-power field [HPF], more than 4 WBCs per HPF, or proteinuria greater than 0.5 g/L) are observed in 36% to 50% of patients with acute appendicitis.22 These findings are more common in women, in patients with perforated appendicitis, and in patients in whom the appendix is located near the urinary tract. No upper limit of urinary WBC or RBC counts has been defined for appendicitis.

Imaging

Helical Computed Tomography

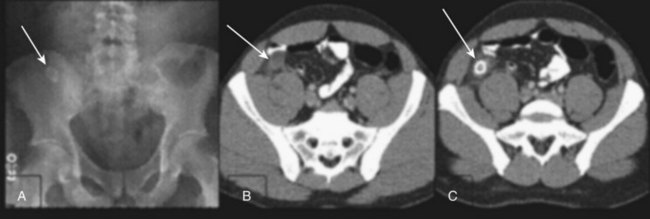

High-resolution helical CT is the diagnostic test of choice for suspected appendicitis (Fig. 39.1). CT findings in appendicitis include an appendiceal diameter greater than 7 to 10 mm, wall enhancement, wall thickening greater than 3 mm, and periappendiceal fat stranding.23,24 The reported sensitivity and specificity of helical CT for appendicitis in adults range between 91% and 96% and 90% and 95%, respectively.25–28

The use of CT as a diagnostic tool for suspected appendicitis has grown explosively in recent years, with adult imaging rates in the United States reported to be greater than 90%.29–31 CT imaging is correlated with a significant decrease in the negative appendectomy rate to less than 9%.29,32,33 The highest benefit of CT in reducing the negative appendectomy rate is appreciated in adult women.30,31 In the elderly, who often have atypical symptoms, the use of helical CT aids in early diagnosis and has reduced the rate of perforated appendicitis from 72% to 51%.9

Intravenous, rectal, or oral administration of a contrast agent to enhance CT imaging in patients with suspicion of appendicitis is controversial. Variations in patient population, contrast protocol, scanner resolution, and radiation dosing all contribute to reported diagnostic accuracy. Contrast agent administered enterally or intravenously enhances the appendiceal wall, lumen, and periappendiceal fat, thereby improving visualization of adjacent intraperitoneal organs. An intravenously administered contrast agent can provide valuable information in patients with little visceral fat but may cause allergic reactions or exacerbate renal insufficiency.34 An enterally administered contrast agent is particularly useful in the identification of perforation, but oral administration of a contrast agent may exacerbate nausea, and 1 to 2 hours is required for the contrast agent to traverse the gut before imaging. Newer-generation multislice CT systems have improved image resolution, even without contrast enhancement. Judicious use of non–contrast-enhanced protocols may reduce diagnostic delays and avoid potential contrast agent–related morbidity.35–37

In children, the sensitivity of helical CT for appendicitis with contrast enhancement is 92% to 100% and the specificity is 87% to 100%.7,28,36 The relative paucity of intraabdominal fat in children decreases the visualization of periappendiceal inflammatory changes, and contrast-enhanced protocols should be used to maximize diagnostic yield.

Ultrasonography

Graded compression ultrasonography is conducted by applying pressure at and around the point of maximum abdominal tenderness. Ultrasonographic findings highly associated with appendicitis include an enlarged, tender appendix greater than 6 mm in diameter with enhancing (hyperechoic) surrounding fat.24 Other signs include an inability to compress the appendix, the presence of periappendiceal fluid, and hypervascularity (Fig. 39.2). Formal ultrasonography for appendicitis has demonstrated sensitivities of 78% to 87% and specificities of 81% to 93% in nongravid adults.25–28 Accuracy is reduced by a thick abdominal wall and intestinal tract; consequently, ultrasonography is best used in thin patients and in children. It is the initial imaging test of choice in pregnant women and children, in whom one wishes to avoid radiation exposure. Ultrasonography is of added benefit when lower abdominal pain may be of pelvic etiology in women of childbearing age.

In children, the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of appendicitis range from 78% to 100% and 88% to 98%, respectively.28,36

Emergency sonography is compelling because it does not require radiation exposure and can be performed rapidly at the bedside by the clinician. However, large variations in sensitivity (65% to 96%), probably related to operator experience, reduce its current utility as a reliable diagnostic tool.38,39

Combined Ultrasound and Computed Tomography Protocols

CT is more sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of appendicitis than ultrasound is in both adult and pediatric populations, and the accuracy of ultrasound is highly operator dependent. However, concern regarding radiation exposure—especially in children—has led to the implementation of protocols involving ultrasound and then CT in which only patients with negative or nondiagnostic findings on ultrasound undergo CT. This serial diagnostic approach has been applied to both adults and children, with sensitivities and specificities ranging from 94% to 100% and 86% to 94%, respectively.7,40–42 Concerns that delays in definitive therapy associated with serial imaging protocols could cause an increase in the rate of perforated appendicitis have not been validated.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with appendicitis consist of a thickened appendiceal wall, a dilated lumen filled with high-intensity material, and periappendiceal enhancement on T2-weighted images. The utility of MRI in diagnosing appendicitis is curtailed by its limited availability, higher cost, and longer image acquisition time. MRI may be appropriate in patients in whom radiation exposure is contraindicated and ultrasonography is nondiagnostic.43,44

Treatment

Early surgical consultation should be obtained whenever appendicitis is suspected (Box 39.3). Delays in surgery raise the risk for appendiceal perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis. Children, pregnant women, and elderly patients with abdominal pain have especially atypical manifestation and are at higher risk for perforation. Surgical consultation should not be delayed for testing, and testing should be undertaken only when the clinical diagnosis is in question.

Box 39.3 Emergency Department Treatment of Patients with Suspected Appendicitis

Control of pain and nausea is both medically rational and humane. Narcotic administration has not been shown to affect the sensitivity of the physical examination in either adults or children or delay the time to diagnostic decision making, although adequately powered studies in children are lacking.45–48 Analgesia with morphine sulfate, hydromorphone, or fentanyl is appropriate. An antiemetic, such as ondansetron, promethazine, prochlorperazine, or metoclopramide, may also be required.

Prophylactic administration of antibiotics has been shown to reduce perioperative infection rates in both simple (nonperforated) and complicated (perforated or gangrenous) appendicitis.49,50 Their administration should be timed in consultation with the surgeon so that high antibiotic tissue levels coincide with the surgical procedure. The antibiotics should be effective against both skin flora and common appendiceal pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Bacteroides species (Table 39.4).

Table 39.4 Options for Preoperative Antibiotics in Patients Suspected of Having Appendicitis

| Adults | Uncomplicated (nonperforated) | Cefoxitin or cefotetan |

| Perforated or gangrenous appendicitis | A carbapenem | |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanate | ||

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ||

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | ||

| A fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), metronidazole | ||

| Children | Ampicillin, gentamicin, metronidazole | |

| Ampicillin, gentamicin, clindamycin | ||

| A carbapenem | ||

| Ticarcillin-clavulanate | ||

| Piperacillin-tazobactam |

Disposition

Patients in whom the findings are a concern despite normal laboratory and imaging results should be admitted for observation and serial abdominal examinations (Box 39.4). Patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain, low risk for appendicitis, and negative diagnostic evaluation results may be considered for discharge if their clinical symptoms improve and they are able to tolerate oral fluids. Arrangements should be made for close follow-up for such patients, who should be given specific instructions to return to the ED if their symptoms worsen. Antibiotics should not be prescribed for discharged patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain. Narcotic analgesics may mask disease progression and are not recommended.

Box 39.4 Disposition of Patients with Undifferentiated Abdominal Pain

Tips and Tricks

If a patient is discharged with the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain, ensure that the plan for that patient is clear and specific. Ask the patient or caregiver to repeat the explained plan. Be sure to include the time and place of the repeat abdominal examination.

Check that the β-human chorionic gonadotropin level is determined in all female patients of childbearing age.

Be certain that the imaging study demonstrates a normal appendix to exclude the diagnosis. Caution should be used when attributing pain to an ovarian cyst or uterine fibroid discovered on ultrasound.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Include the following elements in your documentation:

If a patient with unexplained abdominal pain is discharged, explain why you concluded that the patient did not have acute appendicitis. Include laboratory results, imaging studies, serial examinations, and consultations.

Document in the discharge instructions when the patient with unexplained abdominal pain should undergo a repeat abdominal evaluation: 8, 12, 24, or 36 hours.

Adibe OO, Amin SR, Hansen EN, et al. An evidence-based clinical protocol for diagnosis of acute appendicitis decreased the use of computed tomography in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:192–196.

Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438–451.

Hlibczuk V, Dattaro JA, Jin Z, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast computed tomography for appendicitis in adults: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:51–59.

Howell JM, Eddy OL, Lukens TW, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of emergency department patients with suspected appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:71–116.

Vissers RJ, Lennarz WB. Pitfalls in appendicitis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:103–108.

1 Addis DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, et al. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–925.

2 Prystowsky J, Pugh C, Nagle A. Appendicitis. Curr Probl Surg. 2005;42:694–742.

3 Humes DJ, Simpson J. Acute appendicitis. BMJ. 2006;333:530–534.

4 Oto A, Srinivisan PN, Ernst RD, et al. Revisiting MRI for appendix location during pregnancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:883–887.

5 Hodjati H, Kazerooni T. Location of the appendix in the gravid patient: a re-evaluation of the established concept. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;81:245–247.

6 Vissers RJ, Lennarz WB. Pitfalls in appendicitis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:103–118. viii

7 Kwok MY, Kim MK, Gorelick MH. Evidence-based approach to the diagnosis of appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:690–698.

8 Hiu TT, Major KM, Avital I, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2002;137:995–1000.

9 Storm-Dickerson T, Horattas M. What have we learned over the past 20 years about appendicitis in the elderly? Am J Surg. 2003;185:198–201.

10 Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN. Clinical practice: suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:236–242.

11 Kilpatrick CC, Monga M. Approach to the acute abdomen in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:389–402.

12 Kamin RA, Nowicki RA, Courtney DS, et al. Pearls and pitfalls in the emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:61–72. vi

13 Anderson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28–37.

14 Kwan KA, Nager AL. Diagnosing pediatric appendicitis: use of laboratory markers. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:1009–1015.

15 Sengupta A, Bax G, Paterson-Brown S. White cell count and C-reactive protein measurement in patients with possible appendicitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:113–115.

16 Stefanutti G, Ghirado V, Gamba P. Inflammatory markers for acute appendicitis in children: are they helpful? J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:773–776.

17 Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438–451.

18 Schneider C, Kharbanda A, Bachur R. Evaluating appendicitis scoring systems using a prospective pediatric cohort. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:778–784.

19 Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843–1849.

20 Bhatt M, Joseph L, Ducharme FM, et al. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score in a Canadian emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:591–596.

21 Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–565.

22 Puskar D, Bedalov G, Fridrich S, et al. Urinalysis, ultrasound analysis, and renal dynamic scintigraphy in acute appendicitis. Urology. 1995;45:108–112.

23 Choi D, Park H, Lee Y, et al. The most useful findings for diagnosing acute appendicitis on contrast-enhanced helical CT. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:574–582.

24 Van Randen A, Laeris W, van Es HW, et al. Profiles of US and CT imaging features with a high probability of appendicitis. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1657–1666.

25 Terasawa T, Blackmore C, Bent S, et al. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537–546.

26 Van Randen A, Bipat S, Zwinderman A, et al. Acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of CT and graded compression US related to prevalence of disease. Radiology. 2008;249:97–106.

27 Weston AR, Jackson RJ, Blamey S. Diagnosis of appendicitis in adults by ultrasonography or computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tech Assess Health Care. 2005;21:368–379.

28 Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241:83–94.

29 Raja AS, Wright C, Sodickson AD, et al. Negative appendectomy rate in the era of CT: an 18 year perspective. Radiology. 2010;256:460–465.

30 Wagner PL, Eachempati SR, Soe K, et al. Defining the current negative appendectomy rate: for whom is preoperative computed tomography making an impact? Surgery. 2008;114:276–282.

31 Coursey CA, Nelson RC, Patel MB, et al. Making the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: do more preoperative CT scans mean fewer negative appendectomies? A 10-year study. Radiology. 2010;254:460–468.

32 Krajewski S, Brown J, Phang PT, et al. Impact of computed tomography of the abdomen on clinical outcomes in patients with acute right lower quadrant pain: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 2011;54:43–53.

33 Kim K, Lee CC, Song KJ, et al. The impact of helical computed tomography on the negative appendectomy rate: a multi-center comparison. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:3–6.

34 Pinto Leite N, Pereira J, Cunha R, et al. CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: imaging technique and key diagnostic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:406–417.

35 Anderson B, Salem L, Flum D. A systematic review of whether oral contrast is necessary for the computed tomography diagnosis of appendicitis in adults. Am J Surg. 2005;190:474–478.

36 Howell JM, Eddy OL, Lukens TW, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of emergency department patients with suspected appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:71–116.

37 Hlibczuk V, Dattaro JA, Jin Z, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast computed tomography for appendicitis in adults: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:51–59.

38 Chen SC, Wang HP, Hsu HY, et al. Accuracy of ED sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:449–452.

39 Fox JC, Solley M, Anderson CL, et al. Prospective evaluation of emergency physician performed bedside ultrasound to detect acute appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15:80–85.

40 Adibe OO, Amin SR, Hansen EN, et al. An evidence-based clinical protocol for diagnosis of acute appendicitis decreased the use of computed tomography in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:192–196.

41 Poortman P, Oostvogel HJM, Bosma E, et al. Improving diagnosis of acute appendicitis: results of a diagnostic pathway with standard use of ultrasonography followed by selective use of CT. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:434–441.

42 Gaitini D, Beck-Razi N, Mor-Yosef D, et al. Diagnosing acute appendicitis in adults: accuracy of color Doppler sonography and MDCT compared with surgery and clinical follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1300–1306.

43 Basaran A, Basaran M. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis during pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:481–488.

44 Cobben L, Groot I, Kingma L, et al. A simple MRI protocol in patients with clinically suspected appendicitis: results in 138 patients and effect on outcome of appendectomy. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1175–1183.

45 Wolfe J, Smithline H, Phipen S, et al. Does morphine change the physical examination in patients with acute appendicitis? Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:280–285.

46 Green R, Bulloch B, Kabani A, et al. Early analgesia for children with acute abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 2005;116:978–983.

47 Amoli HA, Golozar A, Keshavarzi S, et al. Morphine analgesia in patients with acute appendicitis: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:586–589.

48 Sharwood LN, Babl FE. The efficacy and effect of opioid analgesia in undifferentiated abdominal pain in children: a review of four studies. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:445–451.

49 Andersen BR, Kallehave FL, Andersen HK. Antibiotics versus placebo for prevention of postoperative infection after appendectomy. Cochrane Database System Rev. 3, 2005. CD001439

50 Lee SL, Islam S, Cassidy LD, et al. Antibiotics and appendicitis in the pediatric population: an American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Clinical Trials Committee systematic review.

51 Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–565.

52 Lintula H, Kokki H, Pulkkinen J, et al. Diagnostic score in acute appendicitis: validation of a diagnostic score (Lintula score) for adults with suspected appendicitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:495–500.

53 Kharabanda A, Taylor G, Fishman SJ, et al. A clinical decision rule to identify children at low risk for appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:709–716.

54 McKay R, Sheperd J. The use of the clinical scoring system by Alvarado in the decision to perform computed tomography for acute appendicitis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:489–493.

55 Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843–1849.

56 Bhatt M, Joseph L, Ducharme FM, et al. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score in a Canadian emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:591–596.

57 Goldman R, Carter S, Stephens D, et al. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr. 2008;153:278–282. (Correction in J Pediatr 2009;154:308-9.)