Appendectomy

Anatomic Principles of Diagnosis and Evaluation

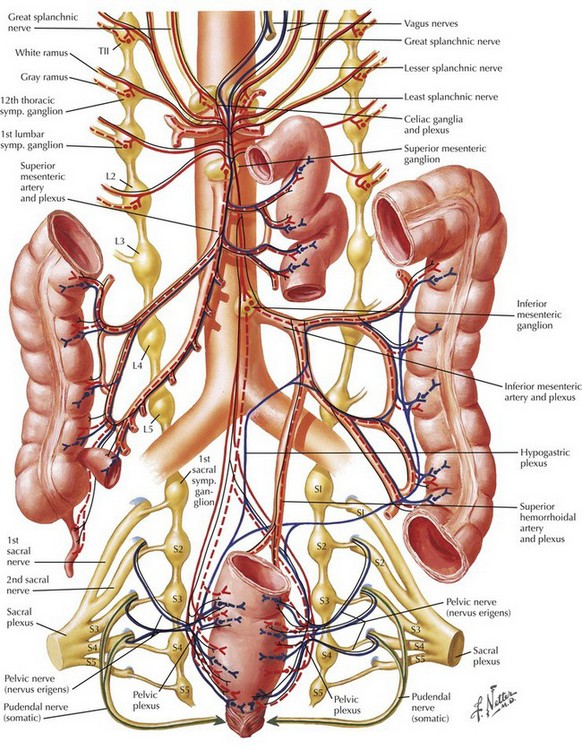

There is considerable variation in the clinical presentation of appendicitis. The classic patient presents with several hours of periumbilical pain that “migrates” to the right lower abdomen, with associated anorexia. The migration of the pain is mediated by the separate innervation of visceral and parietal tissues. Appendiceal obstruction and inflammation, which occur early in the process, cause irritation of autonomic visceral afferent nerves of the superior mesenteric ganglion that result in a nonspecific, poorly localized epigastric or periumbilical pain, secondary to the location and lack of specificity of the autonomic ganglion (Fig. 19-1). Ileus, nausea, anorexia, and diarrhea may also be mediated in this manner. Once inflammation reaches parietal surfaces of the peritoneum (e.g., through perforation), somatic sensory fibers create localized pain in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) with findings of peritonitis, including rigidity, distention, and hyperesthesia.

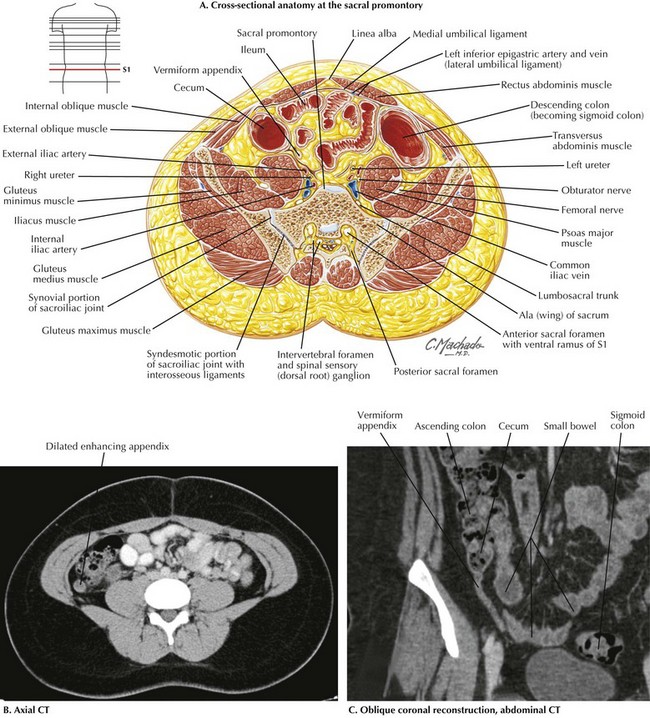

Examination of the patient with appendicitis may further localize inflammation and determine the stage of the diagnosis. Tenderness in the RLQ at McBurney’s point is typical. Well-recognized signs include RLQ pain on palpation of the left abdomen (Rovsing’s sign) and internal rotation of the right hip resulting in motion of deep pelvic musculature, which can cause pain in the case of pelvic appendicitis (obturator sign). Pain with extension of the right hip is caused by motion of the psoas muscle posterior to the cecum (psoas sign) (Fig. 19-2, A).

FIGURE 19–2 Cross-sectional periappendicular anatomy.

CT, Computed tomography; S1, 1st sacral vertebra.

Although the diagnosis of appendicitis may often be made with physical examination alone, computed tomography (CT) has been increasingly used for the evaluation of patients with appendiceal pathology because of its high sensitivity and specificity. Coronal and sagittal reconstructions provide excellent anatomic detail that is useful in surgical planning (Fig. 19-2, B and C).

Surgical Principles

Operative Anatomy

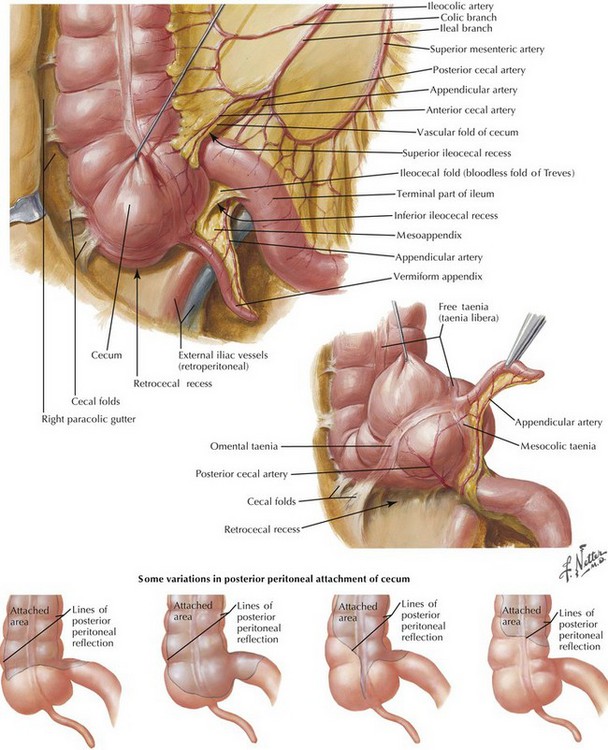

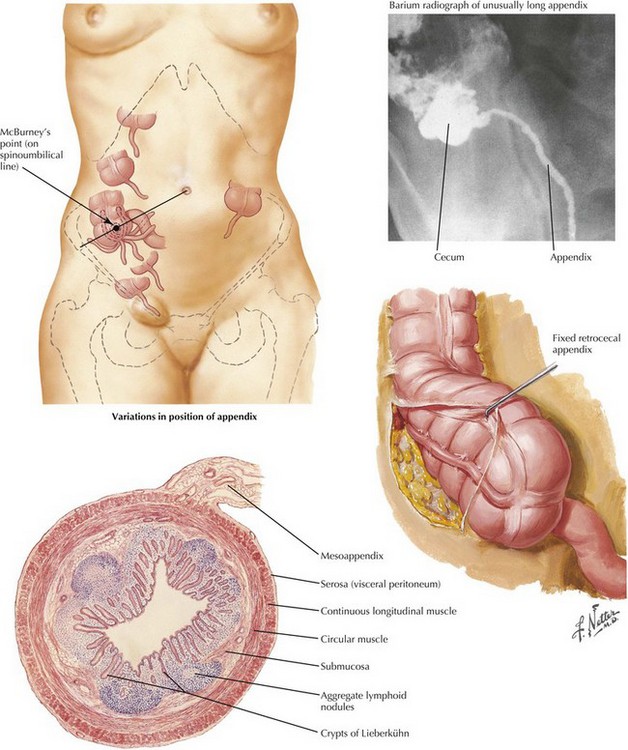

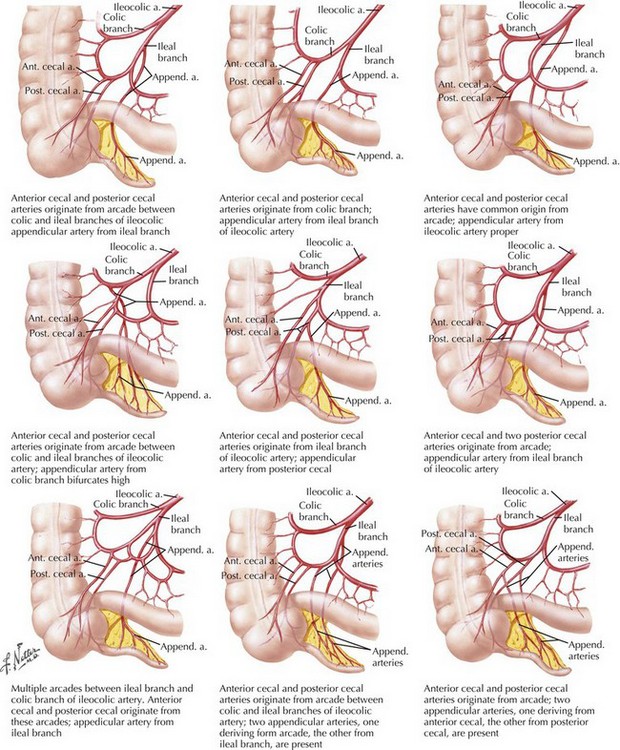

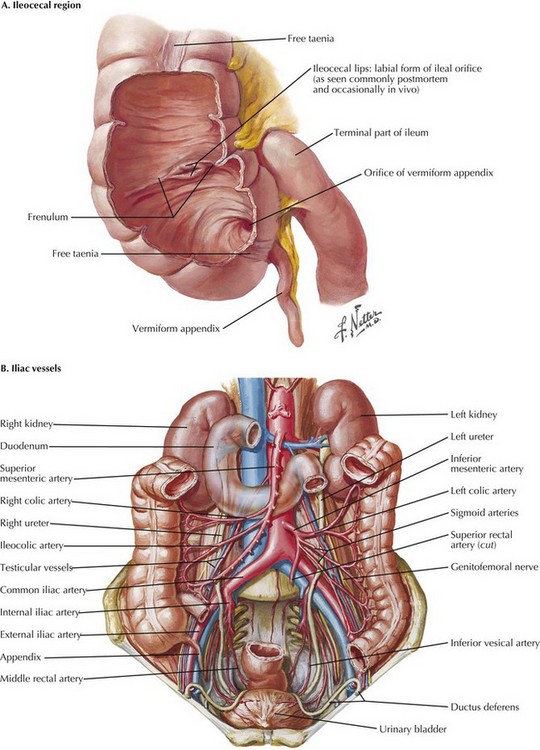

The appendix is a tubular organ located at the base of the cecum; it begins invariably at the fused origin of the taenia coli. The appendix varies considerably in length and orientation relative to the cecum (Figs. 19-3 and 19-4). The appendix receives its blood supply from the appendiceal artery, a terminal branch of the ileocolic pedicle supplied by the superior mesenteric artery. The appendiceal artery travels posterior to the terminal ileum and into the mesoappendix (Fig. 19-5).

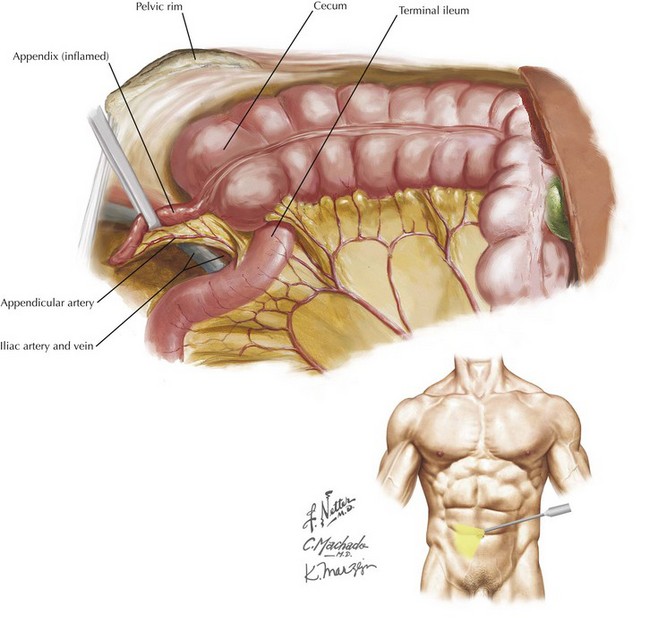

The terminal ileum joins the cecum at the ileocecal valve and generally lies medial to the appendiceal base (Fig. 19-6, A). The ureter lies within the retroperitoneum and is usually located medial to the appendix, although it must be considered when dissection in the region is performed. The appendix often courses over the right iliac vessels into the pelvis (Fig. 19-6, B). Laparoscopically, relational anatomy must be conceptualized because wide visualization can be limited; Figure 19-7 shows a laparoscopic depiction of the relevant anatomy.

Surgical Technique

Open Technique

An open incision is made at McBurney’s point, located one-third the distance between the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus (see Fig. 19-4). This area generally corresponds to the location of the base of the appendix. Subcutaneous tissues are opened to the level of the external oblique muscle by using electrocautery, and its fascia is incised parallel to its fibers. External oblique fibers run inferomedially and are separated along their length, exposing the internal oblique muscle and then the transversus abdominis muscle. These muscles also are preserved and separated through blunt retraction along their length. The peritoneum is opened sharply, with caution taken to avoid injury to underlying viscera.

The right lower quadrant is explored to identify the pathology. A finger sweep can be used to identify an inflamed appendix, which typically feels firm and indurated, revealing its location. Alternatively, identification of the decussation of the taenia coli can be used to identify the base of the appendix. The appendix should be followed to the tip to ensure complete resection. In the case of a retrocecal appendix, the cecum may need to be mobilized fully for adequate exposure (see Fig. 19-4).

Cameron, JL. Current surgical therapy, 10th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Morris, KT, Kavanagh, M, Hansen, P, et al. The rational use of computed tomography scans in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Am J Surg. 2002;183(5):547.

Sauerland, S, Lefering, R, Neugebauer, EA. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004.

Wei, HB, Huang, JL, Zheng, ZH, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized comparison. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(2):266–269.