CHAPTER 19 Appendectomy

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ The appendix is a finger-like evagination of the proximal wall of the cecum. There has been extensive debate as to its evolutionary significance, with many considering it a vestigial organ in humans. More recent thought suggests an immune regulatory role involving immune-mediated maintenance of the normal gut flora.

♦ The appendix is about 10 cm long and 8 mm wide and has a luminal diameter of 1 to 3 mm. The three taenia coli merge at its base. Its sole blood supply is from the appendiceal artery, which originates as a branch of the ileocecal artery. The artery runs in the mesoappendix, the mesentery attaching the organ to the wall of the cecum. The position of the appendix can vary considerably and may be retrocecal in up to 65% of adults. The terminal ileum is an adjacent anatomic landmark.

♦ Because of its position in the right lower quadrant, pain in this area is usually suspicious for appendicitis. Variations in anatomic location, because of such conditions as advanced pregnancy or intestinal malrotation, are infrequent but should be suspected in the appropriate clinical context.

Step 2. Preoperative consideration

Patient preparation

♦ Appendicitis is the usual diagnosis prompting appendectomy.

♦ Although the diagnosis has classically been based on symptoms, physical exam, and laboratory results, there is increasing use of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) in making the diagnosis.

♦ After the diagnosis is made, each patient should receive intravenous fluid hydration, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic suitable to cover enteric organisms, and intravenous analgesics.

♦ Patients should be consented for appendectomy and both laparoscopic and open approaches should be discussed with the patient, as well as the usual complications including bleeding, infection, and damage to intra-abdominal structures.

♦ Expedient operation is advised, although the urgency of the operation is usually dictated by patient symptoms, laboratory results, availability of the operating room or anesthesia resources, and results of imaging studies.

♦ Having consumed nothing by mouth within the preceding 6 hours is usually ideal from an anesthesia standpoint but is not an absolute contraindication to proceeding with the operation.

Equipment and instrumentation

♦ Laparoscopic appendectomy is carried out using standard laparoscopic instruments, including atraumatic graspers and a hook electrocautery.

♦ A 5-mm or 10-mm, 30-degree or 45-degree laparoscope can be utilized. We usually use a 5-mm, 30-degree laparoscope for the procedure.

♦ Additional equipment includes the following:

Endo GIA (Covidien Autosuture, Mansfield, Massachusetts) roticulating stapler with vascular (2.5 mm staple height) and gastrointestinal (3.5 mm staple height) cartridge loads; 45-mm cartridges are usually adequate and are easier to manipulate within the abdominal cavity than the 60-mm cartridges. Current versions of these staplers include a “lavender” (gastrointestinal) and “gold” (vascular) variant. These newer cartridges have changing staple heights along the length of the cartridge.

Endo GIA (Covidien Autosuture, Mansfield, Massachusetts) roticulating stapler with vascular (2.5 mm staple height) and gastrointestinal (3.5 mm staple height) cartridge loads; 45-mm cartridges are usually adequate and are easier to manipulate within the abdominal cavity than the 60-mm cartridges. Current versions of these staplers include a “lavender” (gastrointestinal) and “gold” (vascular) variant. These newer cartridges have changing staple heights along the length of the cartridge. The 10-mm laparoscopic clip applier should also be available in case there is a need to control a bleeding vessel or reinforce the staple line after deployment of the stapler.

The 10-mm laparoscopic clip applier should also be available in case there is a need to control a bleeding vessel or reinforce the staple line after deployment of the stapler.Anesthesia

♦ General anesthesia is required.

♦ Placement of an orogastric (OG) tube will facilitate decompression of the stomach if there is evidence of significant gastric content based on recent oral intake or evidence from computed tomography (CT) scan.

♦ If antibiotics have not already been administered, this should be done prior to incision in the operating room.

♦ A Foley catheter is required in order to decompress the bladder and decrease the risk of bladder injury. In uncircumcised males, make sure to pull the foreskin back over the glans penis after inserting the catheter.

Room setup and positioning

♦ The patient is positioned supine on the operating table.

♦ After general anesthesia is induced and the preceding steps have been performed, the patient’s left arm should be safely tucked and padded. The right arm may be left “out” for anesthesia access.

♦ Ensure that the patient is secure on the table by testing in Trendelenburg and left-to-right roll positions.

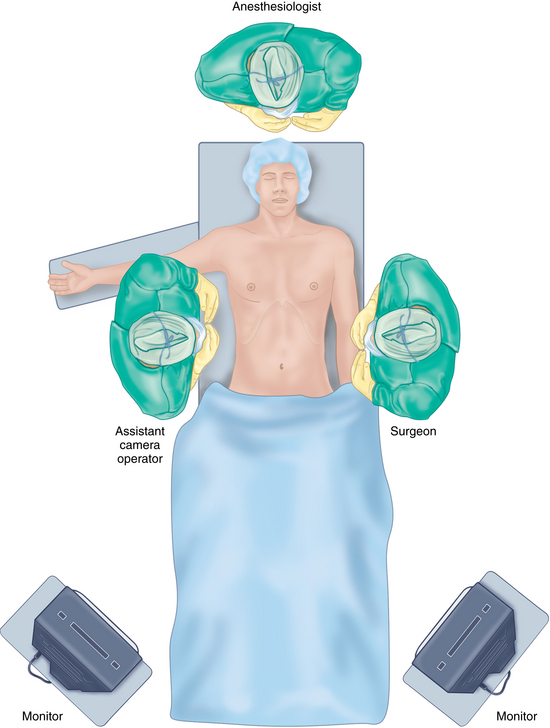

♦ The operating surgeon is positioned on the patient’s left side to the right of the scrub nurse or technician (Figure 19-1).

♦ The assistant is positioned on the patient’s right side.

♦ The main display monitor is positioned off the patient’s right leg directly in line with the appendix and operating surgeon’s line of sight. If an additional display monitor is available, it should be positioned off the patient’s left leg in line with the assistant surgeon. An additional monitor will reduce the assistant’s neck strain but may increase difficulty in using the laparoscope because of the viewing angle and fulcrum effect.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ The operating ports are a 12-mm and 5-mm port. The camera port can be 5 mm or 10 mm.

♦ The camera port is placed on the superior border of the umbilicus. Either a Veress needle or the Hassan technique may be used to gain access to the abdominal cavity.

♦ After establishing access, the abdomen is insufflated with carbon dioxide gas to 12 to 15 mmHg.

♦ A cursory laparoscopic examination is performed prior to subsequent port placement to assure the surgeon that there are no immediate contraindications to proceeding.

♦ There are a number of positions for the working ports of a laparoscopic appendectomy. We favor a 3-port (1 camera and 2 working) configuration with 2 variations:

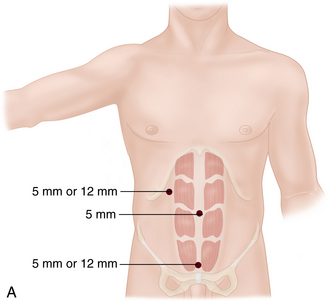

Our favored variation effectively hides the 12-mm incision low on the abdomen, just above the pubic symphysis. It is used when cosmesis is an important consideration and in cases of uncomplicated appendicitis. (Figure 19-2a).

Our favored variation effectively hides the 12-mm incision low on the abdomen, just above the pubic symphysis. It is used when cosmesis is an important consideration and in cases of uncomplicated appendicitis. (Figure 19-2a). With the camera port established, a 5-mm right upper quadrant (RUQ) working port is placed under direct vision. An atraumatic grasper is introduced through this working port and used to guide placement of the final lower midline port.

With the camera port established, a 5-mm right upper quadrant (RUQ) working port is placed under direct vision. An atraumatic grasper is introduced through this working port and used to guide placement of the final lower midline port. The incision should be 1 finger breadth above the superior border of the symphysis in order to avoid injury to the dome of the bladder.

The incision should be 1 finger breadth above the superior border of the symphysis in order to avoid injury to the dome of the bladder. The peritoneum on the lower part of the abdomen tends to have some laxity and can “tent” inward during placement of the larger port. This is minimized by holding tissue up with the open jaws of the atraumatic grasper.

The peritoneum on the lower part of the abdomen tends to have some laxity and can “tent” inward during placement of the larger port. This is minimized by holding tissue up with the open jaws of the atraumatic grasper. Our second variation is used in pregnant patients and in cases where there is evidence of a significant left lower quadrant or lower abdominal inflammatory reaction in response to appendiceal infection.

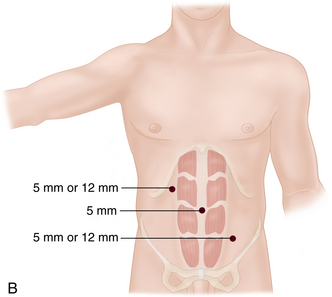

Our second variation is used in pregnant patients and in cases where there is evidence of a significant left lower quadrant or lower abdominal inflammatory reaction in response to appendiceal infection. Here, to avoid a suprapubic port, we place the 12-mm port in the RUQ and a 5-mm port in the left lower quadrant (LLQ). This configuration may also provide a more comfortable range of motion if a stapler is being used to transect the appendix and mesoappendix (Figure 19-2b).

Here, to avoid a suprapubic port, we place the 12-mm port in the RUQ and a 5-mm port in the left lower quadrant (LLQ). This configuration may also provide a more comfortable range of motion if a stapler is being used to transect the appendix and mesoappendix (Figure 19-2b).♦ Remember that the laparoscope can be moved to either of the working ports to facilitate better exposure of the appendix or to better assist the surgeon.

♦ There are now published reports of early experience with appendectomy using single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), particularly in the pediatric population, as well as natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES).

Procedural steps

Identification of the appendix

♦ After camera and working port access has been established, the patient should be placed in 15- to 30-degree Trendelenburg position and rolled a similar extent to the patient’s left. This will allow for better visualization of the right lower quadrant (RLQ).

♦ Identify anatomic landmarks (pelvic brim, right colon, sigmoid colon) to assist in recognizing the overall abdomen and help confirm the source of pathology.

♦ Begin by grasping normal-appearing small bowel and retracting it toward the left upper abdomen.

♦ Large blind sweep of bowel is discouraged, as this increases the risk of a hollow viscus injury or breaking open and spreading infection from an infected fluid collection. Bowel may also need to be removed from the pelvis, and loops may also be adhered to areas of local inflammation and infection in the RLQ.

♦ If possible, use a laparoscopic suction irrigator in one hand and an atraumatic grasper in the other, and suction reactive ascites or purulence as it is encountered. In addition to making it easier to visualize the operative field, this action will also remove infected fluid that might potentially spread and provide a focus for future abscess formation.

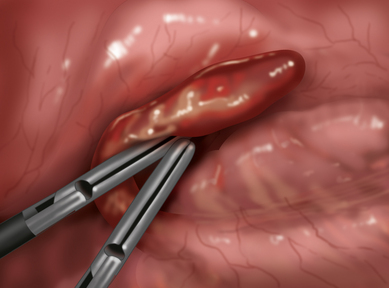

♦ At this point, significant appendicitis, if present, should not be difficult to visualize if the appendix originates from the anterior or inferior wall of the cecum or if there is a perforation (Figure 19-3).

♦ The appendix may be difficult to visualize if it is retrocecal or if there is early infection that produces a minimal local inflammatory reaction. Locating and following one of the three taenia coli may help in locating the appendix, as these merge at its base.

♦ Often, complete visualization of the appendix will require two additional maneuvers:

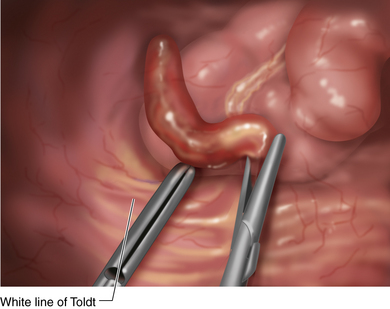

Division of the cecal fascia fused to the abdominal wall in the LLQ. This will allow for inferior and lateral to medial mobilization of the cecum in order to better locate a retrocecal appendix.

Division of the cecal fascia fused to the abdominal wall in the LLQ. This will allow for inferior and lateral to medial mobilization of the cecum in order to better locate a retrocecal appendix. Avoid extensive lateral to medial dissection of the cecum, as this brings one into the area of the iliac vessels and right ureter.

Avoid extensive lateral to medial dissection of the cecum, as this brings one into the area of the iliac vessels and right ureter. Identification of the terminal ileum. This will allow identification of the ileocecal ligament (fold of Treves), which can be grasped, elevated, and manipulated to better locate or characterize the pathologic anatomy of the appendix. Rigorous retraction or manipulation of an inflamed terminal ileum may result in bowel injury (Figure 19-4).

Identification of the terminal ileum. This will allow identification of the ileocecal ligament (fold of Treves), which can be grasped, elevated, and manipulated to better locate or characterize the pathologic anatomy of the appendix. Rigorous retraction or manipulation of an inflamed terminal ileum may result in bowel injury (Figure 19-4).♦ Because of the extent or stage of the disease, the appendix may be easy to locate or may be unrecognized against a background of inflammation, necrosis, or infection.

♦ Be prepared for significant tissue friability and bleeding, which will hinder visualization of the diseased appendix.

♦ Have suitable equipment available to allow safe completion of the procedure:

Division of the appendiceal stump

♦ For early appendicitis, a window is first created in the mesoappendix. The appendiceal artery is controlled by placement of a series of 10-mm Endo clips and is then transected. An Endo GIA vascular stapler load may also be used for controlling and transecting the artery. The appendix is removed after placing double Endoloops at its base or transecting it with an Endo GIA gastrointestinal stapler load.

♦ Organs with more advanced inflammation (serositis, global edema, suppuration, or gangrene without perforation) should have the mesoappendix controlled with a surgical staple load if possible, because the inflammation and edema may make it difficult to easily locate the appendiceal artery for clipping. Likewise, the appendiceal stump may be severely damaged down to its base and may require stapling onto the cecum:

Partial cecectomy, if performed because of inflammation or infection of the base of appendix, is generally tolerated without clinical sequelae.

Partial cecectomy, if performed because of inflammation or infection of the base of appendix, is generally tolerated without clinical sequelae. Carefully inspect the mesoappendix staple line for bleeding. Use laparoscopic clips as needed for control of bleeding. The use of electrocautery may increase the risk of injury to bowel, colon, iliac vessels, or ureter.

Carefully inspect the mesoappendix staple line for bleeding. Use laparoscopic clips as needed for control of bleeding. The use of electrocautery may increase the risk of injury to bowel, colon, iliac vessels, or ureter.♦ The appendix should be grasped by noninflamed tissue if possible to avoid perforation and possible soilage of the abdominal cavity. Other options include use of an Endoloop on the appendix or partial transection (using stapler or Endoloop) at viable tissue and removal of the diseases—usually distal portion—in an Endo Catch bag or other retrieval device.

♦ In instances where there is considerable inflammation, appendiceal perforation with local containment, abscess, or complete degeneration of the appendix itself without fecal contamination, it is usually wise to avoid extensive manipulation of the cecum or widespread dissection in order to attempt to visualize innate anatomy. This may result in damage to small bowel or cecal perforation and convert a locally controlled infection into gross soilage of the abdominal cavity.

Leave a pelvic surgical drain in place, and consider an additional drain in the area of the right colonic gutter if extensive irrigation, aspiration, and debris removal has been conducted.

Leave a pelvic surgical drain in place, and consider an additional drain in the area of the right colonic gutter if extensive irrigation, aspiration, and debris removal has been conducted.♦ In instances where there is complete degeneration of the appendix itself with fecal contamination, it is usually wise to convert to an open procedure by means of a lower midline laparotomy. In these instances, it has been our experience that even advanced laparoscopic skills cannot assure a safe tissue repair and good local infection control.

Closure

♦ Observe the surgical site under reduced pneumoperitoneum (6 to 10 mmHg) to check for bleeding prior to desufflating the abdomen and closure.

♦ Close the fascia of the 12-mm port site if technically possible. Skin incisions may be closed with tissue adhesive, absorbable subcuticular suture, or surgical staples.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ The patient can be typically cared for on the regular surgical ward with intravenous fluids and pain medications.

♦ The orogastric tube and Foley catheter can be removed at the end of the operation.

♦ Intravenous (IV) antibiotics may be continued for 24 to 72 hours after operation in cases of acute, suppurative, necrotic, or perforated appendicitis.

♦ Early appendicitis may only require perioperative IV antibiotic use.

♦ Clear liquids can be initiated as tolerated. Patients are encouraged to ambulate and use incentive spirometry as early as possible to prevent DVT and atelectasis.

♦ Infectious complications related to the procedure range from 2% to 6% and include the following:

♦ Other complications occur, on average, up to 2% of the time and include the following:

♦ Patients may return to full activity when they no longer require pain medication. This is usually between 1 and 7 days after surgery. Persistence of lower abdominal pain; episodes of diarrhea, dysuria, or urinary frequency; low-grade fevers; or persistent malaise should raise the suspicion of intra-abdominal abscess or some other infection or complication.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ Either a Veress needle or the Hassan technique may be used to gain access to the abdominal cavity. The Hassan technique allows for a more controlled access but is not without complication itself.

♦ If an Endo GIA stapler was used to control the appendiceal artery, inspect the transected staple line very carefully under reduced intra-abdominal pressure to check for bleeding. Significant edema or inflammation of the mesoappendix as a result of adjacent appendicitis can predispose to suboptimal stapler performance and subsequent staple line bleeding.

♦ Always have a laparoscopic clip applier available in case there is the need to control bleeding from the appendiceal artery.

♦ The transected finger of a surgical glove may also be used to retrieve the appendix from the abdomen after transection. This mode of extraction is best suited for specimens with early appendicitis.

♦ A Foley catheter is mandatory for all cases to minimize the risk of bladder injury. If injury is suspected, infuse the Foley catheter with 250 mL of normal saline to which 50 mg of methylene blue has been added in order to check for a dye leak in the abdomen.

Dutta S. Early experience with single incision laparoscopic surgery: eliminating the scar from abdominal operations. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44;9:1741-1745.

Horgan S, Cullen JP, Talamini MA, et al. Natural orifice surgery: initial clinical experience. Surg Endosc. 2009;23;7:1512-1518.

Katsuno G, Nagakari K, Yoshikawa S, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a comparison with open appendectomy. World J Surg. 2009;33;2:208-214.

Loh A, Loosemore R, Taylor S, et al. Technique for laparoscopic appendicectomy. Br J Surg. 1992;79(12):1386-1387.

Smith HF, Fisher RE, Everett ML, et al. Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. J Evol Biol. 2009;22(10):1984-1999.

Wei HB, Huang JL, Zheng ZH, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized comparison. Surg Endosc. 2009;24;2:266-269.