67 Aortic Ultrasound

• Bedside ultrasound has emerged as a powerful tool for the diagnosis and disposition of patients with a suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or rupture of an AAA.

• Ultrasound has improved time to diagnosis and time to disposition in patients requiring operative intervention.

• The abdominal aorta must be seen in its entire length to rule out an AAA.

Introduction

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) can be a challenging diagnosis to make and a deadly diagnosis to miss. Patients may be asymptomatic until rupture, or they may have vague complaints such as chronic abdominal or back pain. Frequently, these symptoms are misdiagnosed as less deadly processes, such as renal colic.1,2 Once ruptured, time to diagnosis is the biggest determinant of survival.3 Commonly relied on methods of diagnosis, such as computed tomography (CT), may delay care and result in patient decompensation. Bedside ultrasound has emerged as a powerful tool in the diagnosis and disposition of patients with a suspected AAA or rupture of an AAA. When used properly, bedside ultrasound improves the time to diagnosis and survival.4

What We are Looking for

Because the signs and symptoms of an AAA may be vague and nonspecific, bedside ultrasound of the aorta is indicated in the following clinical scenarios: abdominal pain, back pain, flank pain, unexplained hypotension, syncope, cardiac arrest, or known history of an aneurysm.5,6 The goal of bedside ultrasound is to measure the size of the abdominal aorta and exclude the presence of an AAA. When rupture of an AAA is suspected, the peritoneum should also be evaluated with focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) to search for free fluid.

Supporting Evidence

A large amount of research has confirmed bedside ultrasound to be a useful and lifesaving tool in the emergency department (ED). Tayal et al. conducted a prospective study of the accuracy and outcome of bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of AAA by emergency physicians. They evaluated 125 patients suspected of having an AAA with bedside ultrasound. Twenty-nine patients were found to be positive for AAA, for a positive predictive value of 93% and a negative predictive value of 100%. The sensitivity was 100% with a specificity of 98% for 10 of the 27 patients found to have an AAA, and disposition was immediate to the operating room without a confirmatory study.3,7

Another emergency medicine study performed in 2005 evaluated 238 patients who arrived at the ED with symptoms suggestive of a ruptured AAA. Third-year emergency medical residents, trained according to guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, performed all ultrasound examinations. Thirty-six aortic abnormalities were diagnosed with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 100% for this end point in comparison with “gold standard” diagnostic testing.8

Knaut et al. assessed the accuracy of measurements taken by emergency physicians via ultrasound versus measurements taken by CT. They found that in all cases, their measurements approximated those found on CT within 1.41 cm or less.9

Plummer et al. randomized patients to ultrasound versus standard-of-care diagnostics and compared time to diagnosis and to the operating room. Ultrasound improved time to diagnosis (5.4 versus 83 minutes) and improved time to disposition for patients requiring operative intervention (90 versus 12 minutes).4

Scanning Protocols

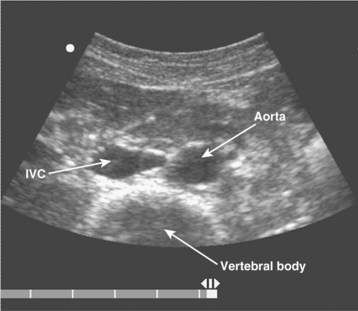

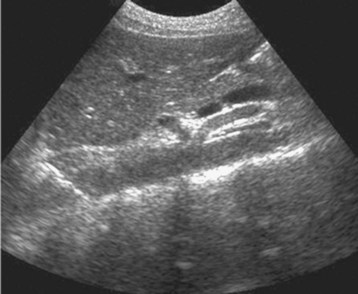

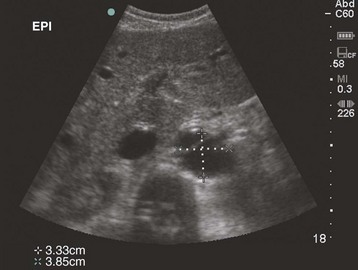

The examination begins just below the patient’s xiphoid process. With the indicator pointing toward the patient’s right, the transducer should be facing straight down to the patient’s back (Fig. 67.1). Although the aorta may be identified immediately, some effort is frequently required to orient the sonographer to the anatomy. The easiest landmark to identify initially is the vertebral body. It is seen as a hyperechoic (white) arc casting a dark acoustic shadow, usually near the bottom of the screen. Just above the vertebral body, two circular, anechoic (black) vessels should be seen (Fig. 67.2). The aorta lies to the patient’s left and the inferior vena cava (IVC) lies to the patient’s right. The IVC is oval shaped and compressible and has thinner walls. The aorta is round, noncompressible, thicker walled, and pulsatile. A measurement should be taken in this transverse orientation, from outer wall to outer wall in both the anterior-posterior and side-to-side planes (Fig. 67.3). While maintaining contact with the skin, the transducer should be moved caudally to follow the course of the aorta. From this point, the branches of the aorta can be seen, and the first branch is the celiac trunk. Caudally, the superior mesenteric artery may also be seen, followed by the bifurcation of the celiac trunk, which is often referred to as the “seagull sign” (Fig. 67.4). As the examination proceeds caudally, a second measurement should be taken midway between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus. Theoretically, this should be near the origin of the renal arteries. The measurement should be taken in the transverse orientation, from outer wall to outer wall and in both the anterior-posterior and side-to-side planes.

The examination continues caudally until the aorta is seen to bifurcate into the common iliac arteries just above the xiphoid process. Once this bifurcation is identified, a third measurement should be taken just above this location in the same manner described previously. The examination concludes with evaluation of the aorta in the longitudinal, or sagittal, plane. Beginning again just caudal to the xiphoid process, the transducer is now placed with the indicator directed toward the patient’s head. It is frequently necessary to move the transducer slightly toward the patient’s left side to visualize the aorta (Fig. 67.5). The aorta is distinguished from the IVC as described previously. This longitudinal view of the aorta allows additional information and frequently details suspected abnormalities. Measurements of the diameter of the aorta should not be done in this plane. Underestimation of the diameter may occur if the beam is off center, known as the “cylinder” artifact.

Abnormal Findings

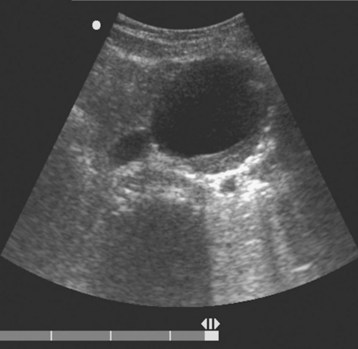

An AAA is defined as an aortic diameter greater than 3 cm or greater than 50% of normal. This diagnosis can easily be made with simple measurements of aortic diameter (Fig. 67.6). Frequently, mural thrombus is seen within the lumen of an AAA as a result of decreased blood flow at the periphery of the vessel (Figs. 67.7 and 67.8). Thrombus is seen as a hypoechoic (dark gray) crescent along the wall of the aneurysm. The type of aneurysm may also be apparent by examining the aorta in multiple dimensions. A fusiform aneurysm will be dilated in a uniform manner around the circumference of the vessel, whereas a saccular aneurysm is a focal dilation of one aspect of the vessel. If an aneurysm is found, the peritoneum should be evaluated for the presence of free fluid with a FAST examination (Fig. 67.9).

Pitfalls

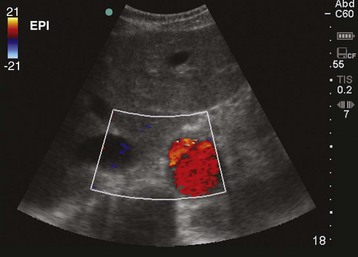

Frequently, a beginning sonographer has difficulty identifying and following the abdominal aorta. Patient habitus and the presence of bowel gas may result in a large amount of hazy gray scatter artifact. To initially identify the aorta, a helpful first step is increasing the overall depth of the image. Some patients may require a depth of 30 cm to “see” far enough into the abdomen. The vertebral body makes a helpful landmark because it typically stands out among the other structures in the abdomen. Careful evaluation of the image for pulsations or use of the color flow box may help in initially identifying the aorta (Fig. 67.10).

Once the aorta has been identified, another common pitfall is an inability to follow the aortic course to its bifurcation because of bowel gas and body habitus.10 To overcome this challenge, application of steady pressure from the subxiphoid area to the umbilicus will frequently cause bowel gas to disperse enough to allow a sufficient image. Additionally, the patient can be placed in either the right or left decubitus position to help displace abdominal gas.

Once technical difficulties have been overcome, the sonographer should be mindful to avoid diagnostic errors. Bedside ultrasound seeks to identify the presence of an aneurysm and is most sensitive when used for this purpose. Because the aorta is a retroperitoneal organ, it most often ruptures into this space, thus making diagnosis difficult. Although free fluid may be seen within the peritoneum as described earlier, this is a rare location for rupture. Rupture of an AAA should be assumed in any patient with an aneurysm and evidence of acute decompensation (e.g., hypotension). The abdominal aorta must be seen in its entire length to rule out an AAA.10 Aneurysms are frequently focal and confined to a relatively small portion of the vessel, so evaluation of only portions of the aorta may result in overlooking a significant aneurysm.

Costantino TG, Bruno E, Handly N, et al. Accuracy of emergency medicine ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:455–460.

Kuhn M, Bonnin RL, Davey MJ, et al. Emergency department ultrasound scanning for abdominal aortic aneurysm: accessible, accurate, and advantageous. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:219–223.

Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: rapid ultrasound in shock in the evaluation of the critically ill. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:29–56.

Plummer D, Clinton J, Matthew B. Emergency department ultrasound improves time to diagnosis and survival in ruptured AAA (abstract). Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:147.

Tayal VS, Graf CD, Gibbs MA. Prospective study of accuracy and outcome of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 2 years. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:867–871.

1 Marston WA, Ahiquist R, Johnson G, Jr., et al. Misdiagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16:17–22.

2 Beede SD, Ballard DJ, James EM, et al. Positive predictive value of clinical suspicion of abdominal aortic aneurysm: implications for efficient use of abdominal ultrasonography. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:549–551.

3 Tayal VS, Graf CD, Gibbs MA. Prospective study of accuracy and outcome of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 2 years. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:867–871.

4 Plummer D, Clinton J, Matthew B. Emergency department ultrasound improves time to diagnosis and survival in ruptured AAA (abstract). Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:147.

5 Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: rapid ultrasound in shock in the evaluation of the critically ill. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:29–56.

6 Maitra S, Jarman R, Halford N, et al. When FAST is a FAFF: is FAST scanning useful in non-trauma patients? Ultrasound. 2008;16:165–168.

7 Kuhn M, Bonnin RL, Davey MJ, et al. Emergency department ultrasound scanning for abdominal aortic aneurysm: accessible, accurate, and advantageous. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:219–223.

8 Costantino TG, Bruno E, Handly N, et al. Accuracy of emergency medicine ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:455–460.

9 Knaut A, Kendall J, Patterson R, et al. Ultrasonographic measurement of aortic diameter by emergency physicians approximates results obtained by computed tomography. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:119–126.

10 Blaivas M, Theodoro D. Frequency of incomplete abdominal aorta visualization by emergency department bedside ultrasound. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:103–105.