Chapter 30 Aortic Dissection

3 Describe the DeBakey and Stanford classifications of aortic dissection

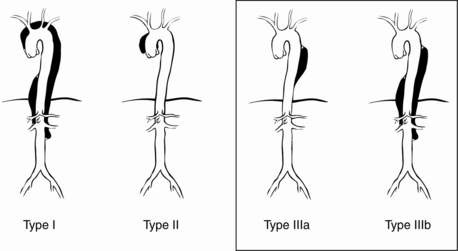

The DeBakey classification describes three types of dissection (Fig. 30-1):

Type I: extends from aortic root to beyond the ascending aorta

Type I: extends from aortic root to beyond the ascending aorta

Type II: involves only the ascending aorta

Type II: involves only the ascending aorta

Type III: begins distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery and has two subtypes

Type III: begins distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery and has two subtypes

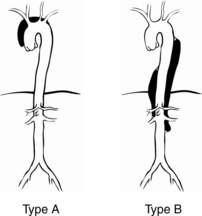

The Stanford classification has two types of dissection (Fig. 30-2):

5 What are the risk factors and associated conditions for dissection?

Hypertension: Present in 70% to 90% of patients with acute dissection.

Hypertension: Present in 70% to 90% of patients with acute dissection.

Advanced age: Mean of 63 years in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD).

Advanced age: Mean of 63 years in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD).

Male sex: Represented by 65% of patients in the IRAD.

Male sex: Represented by 65% of patients in the IRAD.

Family history: Recently recognized is a genetic, nonsyndromic familial form of thoracic aortic dissection. Studies of patients referred for repair of thoracic aortic dissections and aneurysms who did not have a known genetic mutation have indicated that between 11% and 19% of these patients have a first-degree relative with thoracic aortic disease.

Family history: Recently recognized is a genetic, nonsyndromic familial form of thoracic aortic dissection. Studies of patients referred for repair of thoracic aortic dissections and aneurysms who did not have a known genetic mutation have indicated that between 11% and 19% of these patients have a first-degree relative with thoracic aortic disease.

Trauma (deceleration/torsional injury)

Trauma (deceleration/torsional injury)

Congenital and inflammatory disorders: present as Marfan syndrome in almost 5% of total patients in the IRAD and half of those patients under age 40 years. Other associated congenital disorders include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, Turner syndrome, Takayasu and giant-cell aortitis, relapsing polychondritis (Behçet disease, spondyloarthropathies), or confirmed genetic mutations known to predispose to dissections (TGFBR1, TGFBR2, FBN1, ACTA2, or MYH11).

Congenital and inflammatory disorders: present as Marfan syndrome in almost 5% of total patients in the IRAD and half of those patients under age 40 years. Other associated congenital disorders include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, Turner syndrome, Takayasu and giant-cell aortitis, relapsing polychondritis (Behçet disease, spondyloarthropathies), or confirmed genetic mutations known to predispose to dissections (TGFBR1, TGFBR2, FBN1, ACTA2, or MYH11).

Pregnancy: Associated with 50% of dissections in women under age 40 and most frequently occurring in the third trimester. This might be attributable to elevations in cardiac output during pregnancy that cause increased wall stress.

Pregnancy: Associated with 50% of dissections in women under age 40 and most frequently occurring in the third trimester. This might be attributable to elevations in cardiac output during pregnancy that cause increased wall stress.

Circadian and seasonal variations: Producing a higher frequency of dissection in the morning hours and in the winter months.

Circadian and seasonal variations: Producing a higher frequency of dissection in the morning hours and in the winter months.

Iatrogenic: Occurring as a consequence of invasive procedures or surgery, especially when the aorta has been entered or its main branches have been cannulated, such as for cardiopulmonary bypass.

Iatrogenic: Occurring as a consequence of invasive procedures or surgery, especially when the aorta has been entered or its main branches have been cannulated, such as for cardiopulmonary bypass.

6 Describe the common clinical signs and symptoms of aortic dissection

Pain: The most common presenting symptom is chest pain, occurring in up to 90% of patients with acute dissection. Classically, for type A dissections, sudden onset of severe anterior chest pain with extension to the back occurs that is described as ripping or tearing in nature. However, in the IRAD, pain was more often described as sharp rather than ripping or tearing. The pain is usually of maximal intensity from its inception and is frequently unremitting. It may migrate along the path of the dissection. The pain of aortic dissection may mimic that of myocardial ischemia. Patients with type B dissections are more likely to be seen with back pain (64%) alone.

Pain: The most common presenting symptom is chest pain, occurring in up to 90% of patients with acute dissection. Classically, for type A dissections, sudden onset of severe anterior chest pain with extension to the back occurs that is described as ripping or tearing in nature. However, in the IRAD, pain was more often described as sharp rather than ripping or tearing. The pain is usually of maximal intensity from its inception and is frequently unremitting. It may migrate along the path of the dissection. The pain of aortic dissection may mimic that of myocardial ischemia. Patients with type B dissections are more likely to be seen with back pain (64%) alone.

Syncope: Syncope is a well-recognized clinical feature of dissection, occurring in up to 13% of cases. Impairments of cerebral blood flow can be due to acute hypovolemia, low cardiac output, or dissection-involvement of the cerebral vessels. Patients with a presenting syncope were significantly more likely to die than were those without syncope (34% vs. 23%), likely because of the frequent correlation with associated cardiac tamponade, stroke, decreased consciousness, and spinal cord ischemia.

Syncope: Syncope is a well-recognized clinical feature of dissection, occurring in up to 13% of cases. Impairments of cerebral blood flow can be due to acute hypovolemia, low cardiac output, or dissection-involvement of the cerebral vessels. Patients with a presenting syncope were significantly more likely to die than were those without syncope (34% vs. 23%), likely because of the frequent correlation with associated cardiac tamponade, stroke, decreased consciousness, and spinal cord ischemia.

7 Describe the common clinical findings associated with aortic dissection

Neurologic symptoms. The reported frequency of neurologic symptoms in pooled data of type A and B dissections approaches 17%; in type A alone, 29% of patients were seen initially with neurologic symptoms, 53% of which represented ischemic stroke. Neurologic complications may result from hypotension, malperfusion, distal thromboembolism, or nerve compression. Acute paraplegia as a result of spinal cord malperfusion has been described as a primary manifestation in 1% to 3% of patients. Up to 50% of neurologic symptoms may be transient.

Neurologic symptoms. The reported frequency of neurologic symptoms in pooled data of type A and B dissections approaches 17%; in type A alone, 29% of patients were seen initially with neurologic symptoms, 53% of which represented ischemic stroke. Neurologic complications may result from hypotension, malperfusion, distal thromboembolism, or nerve compression. Acute paraplegia as a result of spinal cord malperfusion has been described as a primary manifestation in 1% to 3% of patients. Up to 50% of neurologic symptoms may be transient.

Cardiovascular manifestations. The heart is the most frequently involved end-organ in acute proximal aortic dissections.

Cardiovascular manifestations. The heart is the most frequently involved end-organ in acute proximal aortic dissections.

Acute aortic regurgitation may be present in 41% to 76% of patients with proximal dissection and may be caused by widening of the aortic annulus resulting in incomplete valve closure or actual disruption of the aortic valve leaflets from the dissection flap. Clinical manifestations of dissection-related aortic regurgitation span from mere diastolic murmurs without clinical significance to overt congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

Acute aortic regurgitation may be present in 41% to 76% of patients with proximal dissection and may be caused by widening of the aortic annulus resulting in incomplete valve closure or actual disruption of the aortic valve leaflets from the dissection flap. Clinical manifestations of dissection-related aortic regurgitation span from mere diastolic murmurs without clinical significance to overt congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Myocardial ischemia or infarction may result from compromised coronary artery flow by an expanding false lumen that compresses the proximal coronary or by extension of the dissection flap into the coronary artery ostium. This occurs in 7% to 19% of patients with proximal aortic dissections. Clinically, these present as electrocardiographic changes consistent with primary myocardial ischemia and/or infarction. Appropriate treatment of myocardial ischemia ought to be initiated without delay and concomitantly with aortic imaging to evaluate for dissection when both diagnoses are suspected.

Myocardial ischemia or infarction may result from compromised coronary artery flow by an expanding false lumen that compresses the proximal coronary or by extension of the dissection flap into the coronary artery ostium. This occurs in 7% to 19% of patients with proximal aortic dissections. Clinically, these present as electrocardiographic changes consistent with primary myocardial ischemia and/or infarction. Appropriate treatment of myocardial ischemia ought to be initiated without delay and concomitantly with aortic imaging to evaluate for dissection when both diagnoses are suspected. Cardiac tamponade is diagnosed in 8% to 10% of patients seen with acute type A dissections. It is associated with a high mortality and should prompt consideration for emergent drainage and aortic repair.

Cardiac tamponade is diagnosed in 8% to 10% of patients seen with acute type A dissections. It is associated with a high mortality and should prompt consideration for emergent drainage and aortic repair. Hypertension occurs in greater than 50% of patients with dissection, more commonly with distal disease. Ongoing renal ischemia can produce severe hypertension.

Hypertension occurs in greater than 50% of patients with dissection, more commonly with distal disease. Ongoing renal ischemia can produce severe hypertension. Hypotension/shock may present in up to 20% of patients with dissection. This may be a result of cardiac tamponade from aortic rupture into the pericardium, dissection, or compression of the coronary arteries, acute aortic regurgitation, acute blood loss, true lumen compression by distended false lumen, or an intraabdominal catastrophe. Cardiogenic shock is a relatively uncommon complication, found to occur in approximately 6% of cases. This can be due to acute aortic regurgitation or ongoing myocardial ischemia.

Hypotension/shock may present in up to 20% of patients with dissection. This may be a result of cardiac tamponade from aortic rupture into the pericardium, dissection, or compression of the coronary arteries, acute aortic regurgitation, acute blood loss, true lumen compression by distended false lumen, or an intraabdominal catastrophe. Cardiogenic shock is a relatively uncommon complication, found to occur in approximately 6% of cases. This can be due to acute aortic regurgitation or ongoing myocardial ischemia. Peripheral vascular complications can manifest as pulse and/or blood pressure differentials or deficits and occur in approximately one third to one half of patients with proximal dissection. Etiology is partial compression, obstruction, thrombosis, or embolism of the aortic branch vessels, resulting in cerebral, renal, visceral, or limb ischemia. Peripheral pulse deficits should alert the clinician to possible ongoing renal or visceral ischemia unable to be detected from physical examination or laboratory values alone.

Peripheral vascular complications can manifest as pulse and/or blood pressure differentials or deficits and occur in approximately one third to one half of patients with proximal dissection. Etiology is partial compression, obstruction, thrombosis, or embolism of the aortic branch vessels, resulting in cerebral, renal, visceral, or limb ischemia. Peripheral pulse deficits should alert the clinician to possible ongoing renal or visceral ischemia unable to be detected from physical examination or laboratory values alone.

Pulmonary complications may manifest as pleural effusions, which occur most frequently on the left. Causes include rupture of the dissection into the pleural space or weeping of fluid from the aorta as an inflammatory response to the dissection.

Pulmonary complications may manifest as pleural effusions, which occur most frequently on the left. Causes include rupture of the dissection into the pleural space or weeping of fluid from the aorta as an inflammatory response to the dissection.

12 What are the strategies for medical management of dissection and commonly used medications?

Acknowledgment

Key Points Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Aortic Dissection

1. Aortic dissection is classically associated with sudden chest or back pain, a pulse deficit, and mediastinal widening on chest radiograph.

2. The imaging modality (CT, MRI, or TEE) that is most readily available should be the one selected to confirm the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection.

3. An acute type A aortic dissection is a surgical emergency. Although type B dissections are usually managed medically, one third of these patients eventually require surgery because of worsening of the dissection, rupture, malperfusion, or intractable pain. In either case, prompt surgical consultation is recommended.

4. When managing acute aortic dissection, adequate β-blockade must be established before the initiation of nitroprusside to prevent propagation of the dissection from a reflex increase in cardiac output.

5. The use of endovascular stent-grafts will likely play a large role in the management of dissections.

1 Akin I., Kische S., Rehders T.C., et al. Thoracic endovascular stent-graft therapy in aortic dissection. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:552–559.

2 Clouse W.D., Hallett J.W.Jr. Schaff HV, et al: Acute aortic dissection: population-based incidence compared with degenerative aortic aneurysm rupture. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:176–180.

3 Eggebrecht H., Nienaber C., Neuhauser M., et al. Endovascular stent-graft placement in aortic dissection: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:489–498.

4 Ehrlich M.P., Dumfarth J., Schoder R., et al. Midterm results after endovascular treatment of acute, complicated type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1444–1448.

5 Estrera A.L., Miller C.C.III. Safi HJ, et al: Outcomes of medical management of acute type B aortic dissection. Circulation. 2006;114(Suppl 1):I384–I389.

6 Hagan P.G., Nienaber C.A., Isselbacher E.M., et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903.

7 Hiratzka L.F., Bakris G.L., Beckman J.A., et al. 2010 CCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. Circulation. 2010;121:e266–e369.

8 Khoynezhad A., Plestis K.A. Managing emergency hypertension in aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm surgery. J Card Surg. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S3–S7.

9 Leurs L.J., Bell R., Degrieck Y., et al. Endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic diseases: combined experience from the EUROSTAR and United Kingdom Thoracic Endograft registries. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:670–680.

10 Nienaber C., Rousseau H., Eggebrecht H. Randomized comparison of strategies for type-B aortic dissection. The Investigation of Stent Grafts in Aortic Dissection (INSTEAD) trial. Circulation. 2009;120:2519–2528.

11 Olsson C., Thelin S., Stahle E., et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation. 2006;114:2611–2618.

12 Parsa C.J., Schroder J.N., Daneshmand M.A., et al. Midterm results for endovascular repair of complicated acute and chronic type B aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:97–102.

13 Trimarchi S., Nienaber C.A., Rampoldi V., et al. Role and results of surgery in acute type B aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 2006;14(Suppl 1):I357–I364.

14 Yagdi T., Atay Y., Engin C., et al. Impact of organ malperfusion on mortality and morbidity in acute type A aortic dissections. J Card Surg. 2006;21:363–369.

15 Zoli S., Etz C.D., Roder F., et al. Long-term survival after open repair of chronic distal aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1458–1466.