28 Anxiety disorders

Definitions and epidemiology

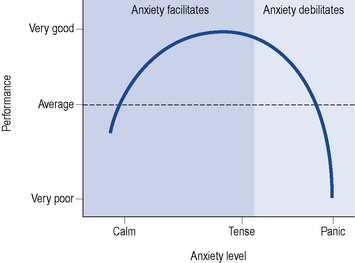

Anxiety is a normal, protective, psychological response to an unpleasant or threatening situation. Mild to moderate anxiety can improve performance and ensure appropriate action is taken. However, excessive or prolonged symptoms can be disabling, lead to severe distress and cause much impairment to social functioning. Figure 28.1 shows that as anxiety levels increase performance/actions increase. However, as the anxiety level increases beyond acceptable or tolerated levels, the performance declines.

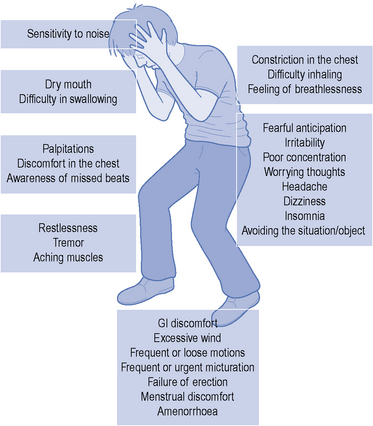

The term ‘anxiety disorder’ encompasses a variety of complaints which can either exist on their own or in conjunction with another psychiatric or physical illness. Symptoms of anxiety vary but generally present with a combination of psychological, physical and behavioural symptoms (Fig. 28.2). Some of these symptoms are common to many anxiety disorders while others are distinctive to a particular disorder. Anxiety disorders are broadly divided into generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), see Table 28.1. Patient testimonials are presented in Box 28.1. Approximately two-thirds of sufferers of an anxiety disorder will have another psychiatric illness. This is most commonly depression and often successful treatment of an underlying depression will significantly improve the symptoms of anxiety. Many patients will also present with more than one anxiety disorder at the same time which can further complicate treatment. Anxiety disorders are the most commonly reported mental illness and as a whole have a lifetime prevalence of 21% (Baldwin et al., 2005) with specific phobias the most commonly reported.

Table 28.1 A brief description of the common anxiety disorders

| Symptoms common to all anxiety disorders | Fear or worry, sleep disturbances, concentration problems, dry mouth, sweating, palpitations, GI discomfort, restlessness, shortness of breath, avoidance behaviour |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) | Persistent (free floating), excessive and inappropriate anxiety on most days for at least 6 months. The anxiety is not restricted to a specific situation |

| Panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) | Recurrent, unexplained surges of severe anxiety (panic attack). Most patients develop a fear of repeat attacks or the implications of an attack. Often seen in agoraphobia (fear in places or situations from which escape might be difficult) |

| Social phobia (or social anxiety disorder) | A marked, persistent and unreasonable fear of being observed, embarrassed or humiliated in a social or performance situation (e.g. public speaking or eating in front of others) |

| Specific phobia | Marked and persistent fear that is excessive or unrealistic, precipitated by the presence (or anticipation) of a specific object or situation (e.g. flying, spiders). Sufferers avoid the feared object/subject or endure it with intense anxiety |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Can occur after an exposure to a traumatic event which involved actual or threatened death, or serious injury or threats to the physical integrity of self or others. The person responds with intense fear, helplessness or horror. Sufferers can re-experience symptoms (flashbacks) and avoid situations associated with the trauma. Usually occurs within 6 months of the traumatic event |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | Persistent thoughts, impulses or images (obsessions) that are intrusive and cause distress. The person attempts to get rid of these obsessions by completing repetitive time-consuming purposeful behaviours or actions (compulsions). Common obsessions include contamination while the compulsion may be repetitive washing or cleaning |

Pathophysiology

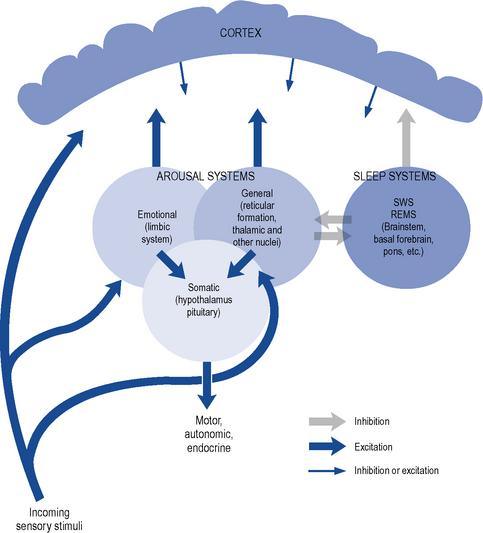

Anxiety occurs when there is a disturbance of the arousal systems in the brain. Arousal is maintained by at least three interconnected systems: a general arousal system, an ‘emotional’ arousal system and an endocrine/autonomic arousal system (Fig. 28.3). The general arousal system, mediated by the brainstem reticular formation, thalamic nuclei and basal forebrain bundle, serves to link the cerebral cortex with incoming sensory stimuli and provides a tonic influence on cortical reactivity or alertness. Excessive activity in this system, due to internal or external stresses, can lead to a state of hyperarousal as seen in anxiety. Emotional aspects of arousal, such as fear and anxiety, are contributed by the limbic system which also serves to focus attention on selected aspects of the environment. There is evidence that increased activity in certain limbic pathways is associated with anxiety and panic attacks.

Treatment

Psychotherapy

Other psychotherapies, although occasionally tried, have a poorer evidence base than CBT and are, therefore, not usually recommended. Self-help is one alternative technique which is recommended (NICE, 2007) for GAD and panic disorder. It involves using materials either alone or in part under professional guidance to learn skills to help cope with the anxiety. The materials such as books, tapes or computer packages can be accessed at home and in the patients’ own time. Some self-help material, however, is of poor quality, so it is probably best used in those who have mild symptoms and who do not need more intensive treatments.

Pharmacotherapy

Benzodiazepines

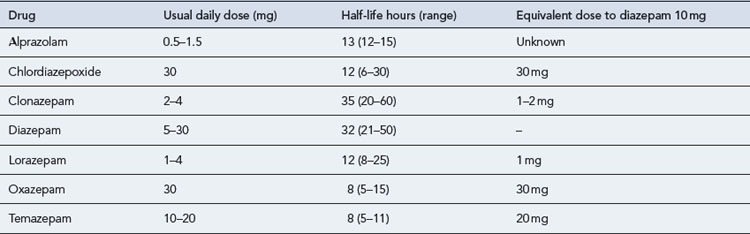

Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed to provide immediate relief of the symptoms of severe anxiety. A number of different benzodiazepines are available (Table 28.2). These drugs differ considerably in potency (equivalent dosage) and in rate of elimination but only slightly in clinical effects. All benzodiazepines have sedative/hypnotic, anxiolytic, amnesic, muscular relaxant and anticonvulsant actions with minor differences in the relative potency of these effects.

Pharmacokinetics

Most benzodiazepines are well absorbed and rapidly penetrate the brain, producing an effect within half an hour after oral administration. Rates of elimination vary; however, with elimination half-lives from 8 to 35 h (see Table 28.2). The drugs undergo hepatic metabolism via oxidation or conjugation and some form pharmacologically active metabolites with even longer elimination half-lives. Oxidation of benzodiazepines is decreased in the elderly, in patients with hepatic impairment and in the presence of some drugs, including alcohol. Benzodiazepines are metabolised through the cytochrome P450 3A4/3 enzyme system in the liver, so significant enzyme inducers (such as carbamazepine) may reduce levels while enzyme inhibitors (e.g. erythromycin) may increase levels (Bazire, 2009).

Mechanism of action

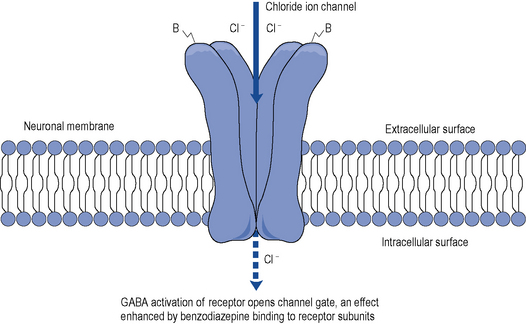

Most of the effects of benzodiazepines result from their interaction with specific binding sites associated with postsynaptic GABAA receptors in the brain. All benzodiazepines bind to these sites, although with varying degrees of affinity, and potentiate the inhibitory actions of GABA at these sites. GABA is the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Neuronal activity in the CNS is regulated by the balance between GABA inhibitory activity and excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate. If the balance swings towards more GABA activity, sedation, ataxia and amnesia occur. Conversely, when GABA is reduced arousal, anxiety and restlessness occur. GABAA receptors are multimolecular complexes that control a chloride ion channel and contain specific binding sites for GABA, benzodiazepines and several other drugs, including many non-benzodiazepine hypnotics and some anticonvulsant drugs (Haefely, 1990) (Fig. 28.4). The various effects of benzodiazepines (hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, amnesic, myo-relaxant) result from GABA potentiation in specific brain sites and at different GABAA receptor types. There are multiple subtypes of GABAA receptor which may contain different combinations of at least 17 subunits (including α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3 and others) and the subtypes are differentially distributed in the brain (Christmas et al., 2008). Benzodiazepines bind to two or more subtypes and it appears that combination with α2-containing subtypes mediates their anxiolytic effects and α1-containing subtypes their sedative and amnesic effects. There is some evidence that patients with anxiety disorders have reduced numbers of benzodiazepine receptors in key brain areas that regulate anxiety responses (Roy-Byrne, 2005). Secondary suppression of noradrenergic and/or serotonergic and other excitatory systems may also be of importance in relation to the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines.

Role in treating anxiety

The benzodiazepines have been used for over 40 years in the treatment of anxiety and can provide rapid symptomatic relief from acute anxiety states. Concerns over dependence and tolerance restrict use to short-term use only. Many clinical trials have shown short-term efficacy in patients with anxiety disorders, although the efficacy shown is in part dependent on the year of publication of the study. Older randomised controlled trials appear to show a larger effect than more recent ones (Martin et al., 2007). Anxiolytic effects have also been reported in normal volunteers with high trait anxiety and in patients with anticipatory anxiety before surgery. However, in subjects with low trait anxiety and in non-stressful conditions, benzodiazepines may paradoxically increase anxiety and impair psychomotor performance.

Although useful for many anxiety disorders, benzodiazepines are not generally recommended for those with panic disorder as the long-term outcome is poor (NICE, 2007). Some patients report worse panic attacks after the benzodiazepines are stopped. Benzodiazepines are also useful at the start of SSRI treatment in OCD and as hypnotics in PTSD (NICE, 2005a,b). They should, however, be used at the lowest effective dose prescribed intermittently where possible and used for no longer than 2–4 weeks.

Choice of benzodiazepine in anxiety

The choice of benzodiazepine depends largely on pharmacokinetic characteristics. Potent benzodiazepines such as lorazepam and alprazolam (Table 28.2) have been widely used for anxiety disorders but are probably inappropriate. Both are rapidly eliminated and need to be taken several times a day. Declining blood concentrations may lead to interdose anxiety as the anxiolytic effect of each tablet wears off. The high potency of lorazepam (~10 times that of diazepam), and the fact that it is available only in 1 and 2.5 mg tablet strengths, has often led to excessive dosage. Similarly, alprazolam (~20 times more potent than diazepam) has often been used in excessive dosage, particularly in the USA. Such doses lead to adverse effects, a high probability of dependence and difficulties in withdrawal.

| Symptoms common to anxiety states | Symptoms relatively specific to benzodiazepine withdrawal |

| Anxiety, panicAgoraphobia | Perceptual distortions, sense of movement |

| Insomnia, nightmares | Depersonalisation, derealisation |

| Depression, dysphoria | Hallucinations |

| Excitability, restlessness | Distortion of body image |

| Poor memory and concentration | Tingling, numbness, altered sensation |

| Dizziness, light-headedness | Skin prickling (formication) |

| Weakness, ‘jelly legs’ | Sensory hypersensitivity |

| Tremor | Muscle twitches, jerks |

| Muscle pain, stiffness | Tinnitus |

| Sweating, night sweats | Psychosisa |

| Palpitations | Confusion, deliriuma |

| Blurred or double vision | Convulsionsa |

| Gastro-intestinal and urinary symptoms |

a Usually only on rapid or abrupt withdrawal from high doses.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects include drowsiness, lightheadedness, confusion, ataxia, amnesia, a paradoxical increase in aggression, an increased risk of falls and fractures in the elderly and an increased risk of road traffic accidents. They are also widely acknowledged as addictive and cause tolerance after more than 2–4 weeks of continuous use (Taylor et al., 2009). Respiratory depression is rare, but possible following high oral doses or parenteral use. Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, can reverse the effects of severe reactions but requires repeated dosing and close monitoring because of its short half-life.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal

Many patients on long-term benzodiazepines seek help with drug withdrawal. Clinical experience shows that withdrawal is feasible in most patients if carried out with care. Abrupt withdrawal in dependent subjects is dangerous and can induce acute anxiety, psychosis or convulsions. However, gradual withdrawal, coupled where necessary with psychological treatments, can be successful in the majority of patients. The duration of withdrawal should be tailored to individual needs and may last many months. Dosage reductions may be of the order of 1–2 mg of diazepam per month. Even with slow dosage reduction, a variety of withdrawal symptoms may be experienced, including increased anxiety, insomnia, hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, perceptual distortions, paraesthesia, muscle twitching, depression and many others (Box 28.2). These may last for many weeks, though diminishing in intensity, but occasionally the withdrawal syndrome is protracted for a year or more. Transfer to diazepam, because of its slow elimination and availability as a liquid and in low dosage forms, may be indicated for patients taking other benzodiazepines. Useful guidelines for benzodiazepine withdrawal are given in the British National Formulary and detailed withdrawal schedules are also available (Lader et al., 2009).

Antidepressant drugs

Antidepressants can provide a long-term treatment option for those with an anxiety disorder. They are generally recommended for those who are unable to commit to or have not responded to psychological therapies. In addition, antidepressants are considered first-line treatment option either alone or in combination with CBT in patients suffering from OCD with moderate or severe impairment (NICE, 2005a). The number needed to treat (NNT) to see one benefit with antidepressants is around five in PTSD and GAD (NICE, 2005b, 2007).

The response rate to antidepressants in anxiety is often lower and takes longer than that seen in depression. Initial worsening of symptoms can occur and high therapeutic doses are often required to improve response (Baldwin et al., 2005).

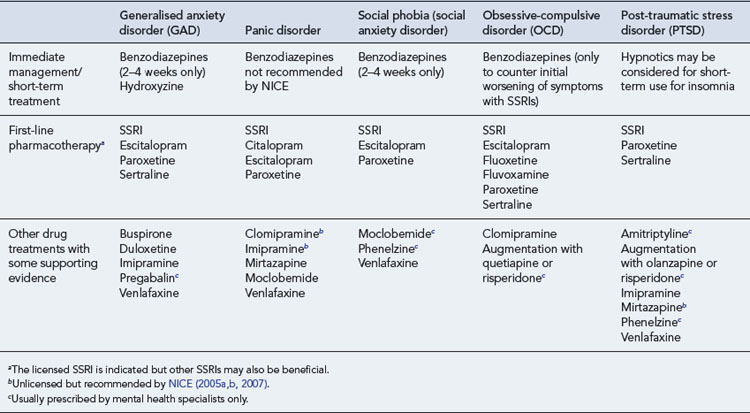

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a broad anxiolytic effect and are considered the first drug options in GAD, panic disorder, social phobia, PTSD and OCD (NICE, 2005a,b, 2007; Baldwin et al., 2005). Individual SSRIs have varying licensed indications across the anxiety disorders but this does not necessarily mean others have no supporting evidence. Where more than one SSRI is licensed in a particular disorder it is not possible to conclude which SSRI would be more effective because of the lack of direct head to head trials. The SSRIs do differ in their interaction potential, side effect profile and ease of discontinuation. Initial worsening of symptoms is common when starting an SSRI in anxiety, so beginning with half the dose than that used in depression is recommended as is reassuring the patient that this is usually only experienced for the first few weeks of treatment. In view of these concerns, the NICE (2007) guidelines for GAD and panic disorder recommend that patients are reviewed every 2 weeks for the first 6 weeks of treatment to monitor for efficacy and tolerability.

Monoamine-oxidase inhibitors

The monoamine-oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are rarely used in practice because of their potential interactions with other medicines and tyramine in the diet. Moclobemide is a reversible MAOI, so causes fewer problematic interactions. Phenelzine and moclobemide are occasionally used by specialists in social phobia following the failure of an SSRI. Phenelzine is also recommended as a third-line treatment option in PTSD (NICE, 2005b).

Other antidepressants

Mirtazapine, an α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, is recommended as an option for PTSD if patients do not wish to participate in trauma focused CBT (NICE, 2005b). Mirtazapine has a lower incidence of nausea, vomiting and sexual dysfunction than the SSRIs but can commonly cause weight gain and sedation.

No other antidepressants are routinely recommended for anxiety disorders, although some such as agomelatine are under clinical trials in anxiety to investigate potential future uses. To reduce the risk of symptoms returning patients should be advised to continue the antidepressant for at least 6 months following improvement of symptoms in GAD and panic disorder and for 12 months in PTSD, OCD and social phobia (NICE, 2005a, 2007; Baldwin et al., 2005). Those with an enduring and recurrent illness, however, may continue for many years, depending on the risk of relapse and severity of symptoms.

For a complete review of the antidepressants, including adverse effects and interactions, see Chapter 29.

Other medications occasionally used in anxiety

Hydroxyzine, a sedating antihistamine, is licensed for the short-term treatment of anxiety in adults at a dose of 50–100 mg four times a day. The clinical evidence only supports its use in GAD (for up to 4 weeks) if sedation is required. NICE supports the use of a sedating antihistamine in the immediate management of GAD but state they should not be used in panic disorders (NICE, 2007).

Pregabalin is licensed for GAD and has shown an anxiolytic effect over placebo after 1 week in adults or 2 weeks in the elderly (Montgomery et al., 2008). Two short-term studies (4 and 6 weeks) suggest that pregabalin 400–600 mg/day is as effective but better tolerated than venlafaxine 75 mg/day XL or lorazepam 6 mg/day. Pregabalin, however, commonly causes dizziness, somnolence and nausea and is more expensive than other medication options in GAD and should be limited to specialist use only after other treatments have failed.

Buspirone, a 5HT1A partial agonist, is licensed for short-term use in anxiety. It is not a benzodiazepine and so does not treat or prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal problems. In GAD, buspirone and other azapirones are superior to placebo in short-term studies (4–9 weeks) but less effective or acceptable than benzodiazepines (Chessick et al., 2006). NICE have said the evidence for buspirone in GAD is equivocal and, therefore, presumably not recommended (NICE, 2007). There is no evidence supporting buspirone in other anxiety disorders.

Propranolol and oxprenolol are both licensed for anxiety symptoms but are probably only useful for physical symptoms such as palpitations, tremor, sweating and shortness of breath. β-Blockers do not have sufficient evidence to support their inclusion in NICE guidelines but intriguingly small pilot studies indicate that giving an immediate course of propranolol following a traumatic event may prevent emerging PTSD (Pitman et al., 2002; Vaiva et al., 2003).

An overview of the recommended drug treatments in anxiety is provided in Table 28.3.

Answers

Questions

Answers

Answer

Baldwin D., Anderson I., Nutt D., et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol.. 2005;19:567-596.

Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory. HealthComm UK: Aberdeen; 2009.

Chessick C.A., Allen M.H., Thase M.E., et al. Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. Issue 3, Art No. CD006115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006115

Christmas D., Hood S., Nutt D. Potential novel anxiolytic drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des.. 2008;14:3534-3546.

Haefely W. Benzodiazepine receptor and ligands: structural and functional differences. In: Hindmarch I., Beaumont G., Brandon S., et al, editors. Benzodiazepines: Current Concepts. Chichester: John Wiley; 1990:1-18.

Lader M., Tylee A., Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:19-34.

Martin J., Sainz-Pardo M., Furukawa T., et al. Review: benzodiazepines in generalized anxiety disorder: heterogeneity based on systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J. Psychopharmacol.. 2007;21:774-782.

Montgomery S.A., Chatamra K., Pauer L., et al. Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in elderly people with generalised anxiety disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;193:389-394.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obsessive compulsive disorder. Clinical Guideline 31. 2005. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG31 Accessed March 2010.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clinical Guideline 26. 2005. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG26 Accessed March 2010.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Anxiety: management of anxiety (panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, and generalised anxiety disorder) in adults in primary, secondary and community care. Clinical Guideline 22. 2007. (amended). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG022NICEguidelineamended.pdf Accessed March 2010.

Pitman R., Sanders K., Zusman R., et al. Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:189-192.

Roy-Byrne P.P. The GABA-benzodiazepine receptor complex: structure, function and role in anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl. 2):14-20.

Taylor D., Paton C., Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, 10th ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2009.

Vaiva G., Ducrocq F., Jezequel K., et al. Immediate treatment with propranolol decreases posttraumatic stress disorder two months after trauma. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:947-949.

Baldwin D. Room for improvement in the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des.. 2008;14:3482-3491.

Garner M., Mohler H., Stein D., et al. Research in anxiety disorders: from the bench to the bedside. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.. 2009;19:381-390.

Katzman M. Current considerations in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:103-120.

The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies has a list of therapists, training resources and general information for the public.. http://www.babcp.com.

Anxiety UK: a national charity for anyone affected by an anxiety disorder.. www.anxietyuk.org.uk.

No Panic: a national charity offering support for suffers of panic attacks, phobias, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Generalised Anxiety Disorder.. www.nopanic.org.uk.