CHAPTER 34 Anterior Hueter Approach for Hip Resurfacing in the Arthritic Patient

Relative contraindications

Imaging and diagnostic studies

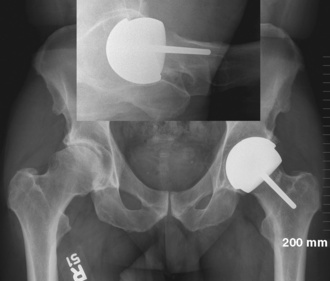

Our hip series for evaluating the patient with osteoarthritis of the hip includes a supine anteroposterior pelvic view that is centered on the hips and that shows the proximal femur down to the diaphysis as well as cross-table lateral views, Dunn views, or both (Figure 34-1). These two radiographs are scrutinized to analyze for structural abnormalities (e.g., insufficient femoral head–neck offset), the integrity of the joint space, and periarticular bone. In the rare case of a patient with radiographic osteoarthritis of the hip joint without a typical clinical history or physical examination, we perform an intra-articular anesthetic injection to determine whether the patient’s symptoms are a result of the radiographic hip degeneration.

Surgical technique

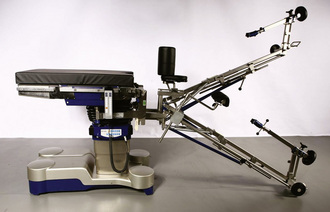

Although the anterior Hueter approach can be performed without a special surgical table, our main experience is with the use of a specialty orthopedic traction table (Figure 34-2). We do not exclude patients on the basis of body mass index or underlying deformity.

Exposure

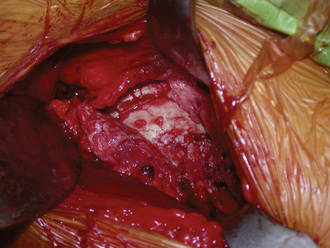

The incision is placed 1 cm to 2 cm posterolateral and 2 cm distal to the anterosuperior iliac spine. The incision is extended distally and posterolaterally toward a line that connects to the fibular head for a total of 6 cm to 10 cm. The subcutaneous tissue is divided with the use of electrocautery until the aponeurosis of the tensor of the fascia lata is identified. The latter is incised longitudinally with a No. 10 blade, with all muscle fibers preserved. Blunt finger dissection is then performed between the medial aspect of the muscle belly (which can sometimes be bipennate) and the aponeurosis. At this point, retractors are placed in between the muscle and its sheath to expose the rectus femoris and the fat that overlies the hip capsule. With the use of electrocautery, this fat is removed to expose the capsule. After incising the fascia over the rectus femoris, blunt dissection is performed to expose the lateral circumflex vessels, which are then ligated and cut. These vessels can bleed briskly, and they deserve attention. Some of the lateral aspects of the rectus femoris and the iliocapsularis muscle can be elevated to maximize the exposure of the hip capsule. It is recommended to release the reflected head of the rectus femoris to facilitate the exposure of the acetabulum. At this point, the capsulotomy is performed with the use of electrocautery from inferomedial to superolateral, and a second transverse capsular incision is made from inferomedial to lateral, leaving a laterally based capsular flap attached to the proximal femur. In some cases, it is preferable to excise the lateral capsular flap to facilitate the delivery of the proximal femur (Figure 34-4). A large cobra retractor is then placed around the proximal femur to retract the tensor muscle laterally, and a blunt Hohmann retractor is placed at the inferomedial femoral neck.

Femoral Head Preparation

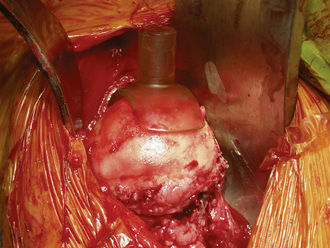

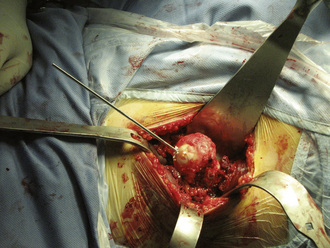

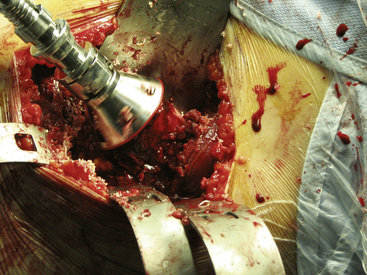

A femoral neck elevator is placed medially on the neck and held by a scrubbed surgical assistant on the opposite side of the patient. A large cobra retractor is placed to gently retract the tensor of the fascia lata laterally. A pointed Hohmann retractor is applied superiorly under the greater trochanter, and the leg is then brought into extension without any traction. The leg is then further externally rotated to 180 degrees. In large male patients, it may be necessary to release the anterior portion of the tensor muscle off of the iliac crest. The femoral head is then sized with the use of femoral head gauges (Figure 34-5). A smooth pin is advanced through the femoral head and into the middle of the femoral neck in about 5 degrees to 10 degrees of valgus relative to the native femoral neck shaft angle, which usually ends up being about 140 degrees (Figure 34-6). A spin-around gauge that corresponds with the femoral implant size is used to ensure the clearance of the femoral head–neck junction. The gauge should hug the inferomedial neck and clear the anterior aspect of the neck. Proximal femur preparation can follow, with the reamers chosen in accordance with preoperative templating and intraoperative findings. We usually recommend starting at least one size larger than the planned size and completing the first cylindrical reaming with osteotomes to provide overall better visualization for the final preparation. The final sequence of femoral head preparation will then vary from one manufacturer to another in terms of stem hole and chamber head (Figure 34-7). It is extremely important to ensure that the trial component can seat fully on the prepared femoral head; marking the endpoint where it should go may be useful.

Acetabular Preparation

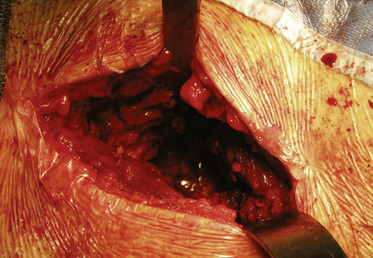

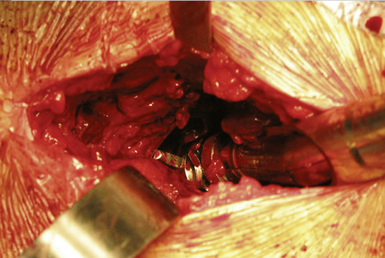

After the femoral head has been reamed definitively, the acetabulum is prepared in accordance with the size chosen on the femoral side. The retractors are taken out, no traction is applied, the rotation is freed up, and the leg is brought into neutral flexion and extension, which leaves the proximal femur to fall posterior to the socket. A long, pointed Hohmann retractor is first placed on the anteromedial lip of the acetabulum to retract the medial soft tissues away, and a second one is placed posteriorly, with the tip on the mid-posterior rim (Figure 34-8). A long knife is then used to debride the socket, and osteophytes are removed with a curved osteotome. Reaming commences with the use of tools that are three sizes smaller than those required for the planned definitive component. Offset reamer handles are critical. The reamers are usually brought in from a superior direction, slightly levering on the femoral neck. Attention is paid to maximize the bony contact between the reamers (Figure 34-9) and the bone, because most resurfacing shells do not have screw holes to supplement a poor press-fit fixation. To prevent soft-tissue damage, we suggest manually inserting and removing each reamer into and from the socket and to attach and detach the reamers to power in situ.

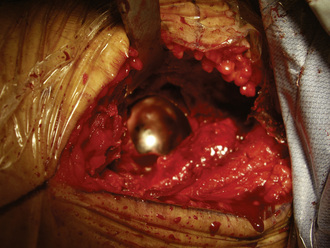

Acetabular Cup Insertion

The tendency is to place the cup in a too-anteverted and vertical position because of soft-tissue interference with the cup inserter. Image intensification or intraoperative x-rays help to ensure proper component positioning. Cup positioning can be assessed by finger palpating the rim to see how closely it matches the see-through gauge. In the coronal plane (i.e., the acetabular component abduction angle), the guide rod should be parallel to a line drawn between the two anterosuperior iliac spines. Acetabular version is then judged from the patient’s longitudinal axis. After proper impaction, component stability is tested with a punch applied manually all around the cup’s periphery to detect any movement. Any remaining overhanging osteophytes can be removed at this point with a curved osteotome to prevent impingement. We often leave some overhanging acetabular rim to minimize the irritation of the iliopsoas tendon. We aim for a cup abduction angle of 45 degrees, with 20 degrees of anteversion (Figure 34-10).

Clinical results

To date, we have performed about 80 hip resurfacing procedures with the use of the anterior Hueter approach and an orthopedic traction table. Four patients have undergone bilateral procedures in the same setting. The mean age of the group is 48 years (range, 29 to 62 years) with the majority (more than 80%) being male (Figure 34-11). In terms of implant positioning, there was a tendency to have more acetabular components in the range of 45 degrees to 55 degrees of abduction, although none of the components was placed in more than 55 degrees of abduction. The femoral component has a tendency toward a slight valgus orientation and an anterior translation. Distally extending the skin incision for 1 cm or 2 cm can help to prevent the conflict between the cup impactor. The anterior translation of the femoral component is probably related to the more difficult access to the posterior femoral neck that occurs with the Hueter approach. Although we are still early in our experience, patients so far have demonstrated excellent recovery with minimal pain.

Conclusion

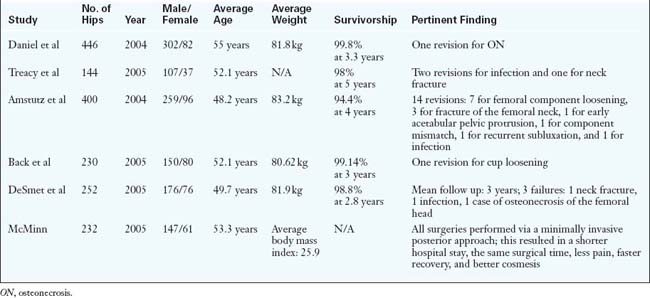

Despite the increasing popularity of resurfacing, most published reports are from implant designers or leading experts in hip resurfacing arthroplasty (Table 34-1). Further long-term studies of this implant as well as reports from independent centers and national registries will help to support generalized use in the orthopedic community. Early published results appear to indicate that hip resurfacing arthroplasty is a viable alternative to total hip arthroplasty for the young active adult. In terms of surgical approach selection, we would urge surgeons to start using the approach that they are most at ease with and to consider the anterior Hueter approach as a strong alternative to preserve femoral head vascularity and to facilitate recovery.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Amstutz H.C., Beaulé P.E., Dorey F.J., Le Duff M.J., Campbell P.A., Gruen T.A. Metal-on-metal hybrid surface arthroplasty: two- to six-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:28-39.

Amstutz H.C., Grigoris P., Dorey F.J. Evolution and future of surface replacement of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 1998;3:169-186.

Back D.L., Dalziel R., Young D., Shimmin A. Early results of primary Birmingham hip resurfacings. An independent prospective study of the first 230 hips. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87B(3):324-329.

Beaulé P.E., Campbell P., Lu Z., et al. Vascularity of the arthritic femoral head and hip resurfacing. JBone Joint Surg. 2006;88A:85-96.

Beaulé P.E., Dorey F.J., LeDuff M.J., Gruen T., Amstutz H.C. Risk factors affecting outcome of metal on metal surface arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop. 2004;418(418):87-93.

Beaulé P.E. Surface arthroplasty of the hip: a review and current indications. Semin Arthroplasty. 2005;16(1):70-76.

Buechel F., Drucker D., Jasty M., Jiranek W., Harris W.H. Osteolysis around uncemented acetabular components of cobalt-chrome surface replacement hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1994;298:202-211.

Daniel J., Pynsent P.B., McMinn D.J. Metal-on-metal resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip in patients under the age of 55 years with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:177-184.

DeSmet K.A. Belgian experience with metal-on-metal surface arthoplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:203-213.

Eastaugh-Waring S.J., Seenath S., Learmonth D.S., Learmonth I.D. The practical limitations of resurfacing hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:18-22.

Reasons for unsuitability included collapse and/or cystic degeneration of the femoral head..

Howie D., Cornish B., Vernon-Roberts B. Resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Classification of loosening and the role of prosthetic wear particle. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1990;255:144-159.

Kabo J., Gebhard J., Loren G., Amstutz H. In vivo wear of polyethylene acetabular components. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B:254-258.

McMinn D.J., Daniel J., Pynsent P.B., Pradhan C. Mini-incision resurfacing arthroplasty of hip trough the posterior approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:91-98.

Siguier T., Siguier M., Brumpt B. Mini-incision anterior approach does not increase dislocation rate: a study of 1037 total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2004;426:164-173.

Treacy R.B., McBryde C.W., Pynsent P.B. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty. A minimum follow-up of five years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87B(2):167-170.

Treuting R.J., Waldman D., Hooten J., Schmalzried T.P., Barrack R.L. Prohibitive failure rate of the total articular replacement arthoplasty at five to ten years. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(2):114-118.