Chapter 21 Anterior endoscopic cervical discectomy

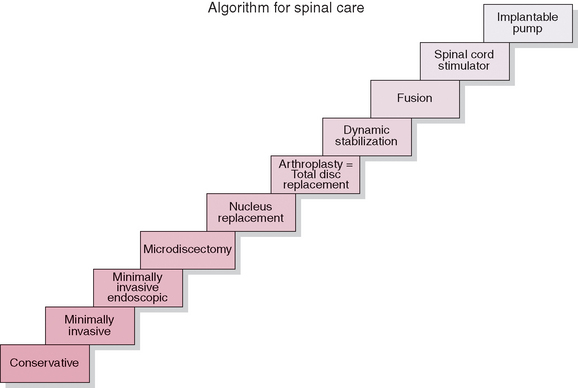

As with most other aspects of medicine and surgery, the understanding, care, and treatment of cervical disc injury has progressed. In the early days of surgical intervention, operating around the cervical spine and spinal cord did not often have satisfactory results, and it was not until the early part of the 1920s that surgery for cervical disc abnormalities became a reasonable option. The treatment of cervical disc injury started out with posterior decompression, and by the late 1940s, decompression with more of an anterior approach became more common and fusion was accepted fairly rapidly. The mainstream or “gold standard” technique for treatment of cervical disc injury for most of the past half century has consisted of anterior decompression and arthrodesis. Throughout this time, decompression without fusion was explored, but not until later have minimally invasive techniques, such as anterior endoscopic cervical discectomy (AECD), been able to make decompression without fusion a viable option. The next horizon in the development of spinal care will likely include percutaneous disc augmentation technologies that one hopes will reduce the need for subsequent surgical intervention and limit the reliance on implant survivability (Fig. 21-1).

Figure 21–1 Algorithm showing progression of types of spinal care from conservative through pump implantation.

The relatively early realization that anterior cervical disc decompression led to instability and often fusion or arthrodesis in kyphosis led to the common practice of performing fusion at the time of anterior cervical decompressive surgery. In comparison with the lumbar spine, posterior decompression of a cervical disc could be accomplished through a small enough entry zone that instability did not result regularly. It is these types of concepts that have allowed for the evolution of cervical disc surgery to the minimally invasive stage, with the realization that decompression of a cervical disc that does not remove too much of the surrounding structure can in fact be performed without resulting in instability. This procedure can even be performed in a minimally invasive fashion, and the advent of endoscopic technology allows for cervical decompression without the usual requirement for index fusion (Fig. 21-2).

Considering the history of the understanding of the cervical spine, it is no surprise that surgery for cervical disc abnormalities has had difficulties since its very beginning. The reasons are not only the technical difficulties with regard to operating on the cervical spine but also the lack of diagnostic tools and proven successful surgical experience. Differentiating between cervical disc herniations and other diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, was often difficult because commonly there were few or nonspecific symptoms, pointing early clinicians to cervical pathology, and because results of simple radiographic examinations were often inconclusive, in that the neurologic signs and symptoms seemed to predominate in the motor system [1].

As early as 1911, Bailey and Casamajor discussed osteoarthritis of the cervical spine and suggested that the primary pathologic change is thinning of the intervertebral discs with resultant trauma to the vertebral end plates and osteophyte production, which causes symptoms. This narrowing of the disc space decreases the size of the neural foramen and compresses the facet joints. The spurs that then develop in response to this compression increase joint stress [2]. The primary cause of disc degeneration is generally assumed to be deficient nutrition, desiccation progressing with aging. The wear and tear of everyday activities and, occasionally, acute trauma are often additive to other, predisposing factors. Herniations of the cervical intervertebral discs with compression of the spinal cord have been described since 1928, when Stookey and other clinicians pointed out the similarities between the symptoms that arise as a result of a medial herniation and the more commonly associated symptoms of degenerative disease of the cervical spine [3,4]. That there is difficulty in diagnosing cervical disease is nothing new. It was a constant challenge for early clinicians to evaluate both the clinical symptoms and the radiologic findings in patients complaining of cervical and/or radicular symptomatology.

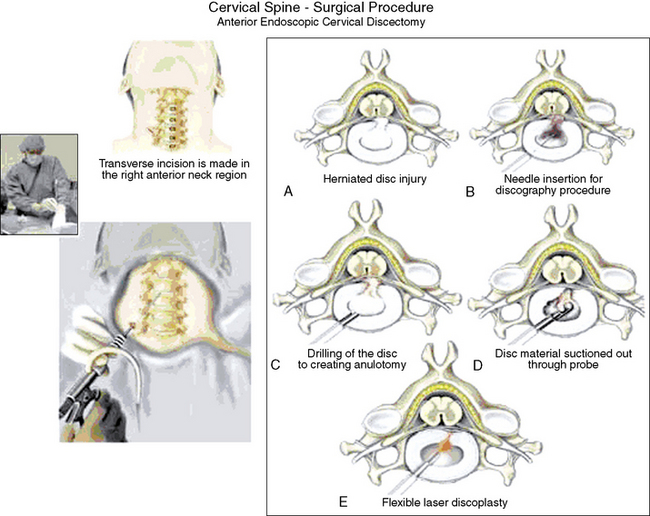

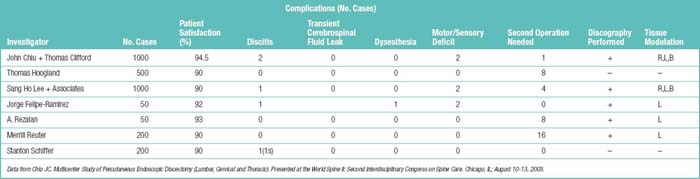

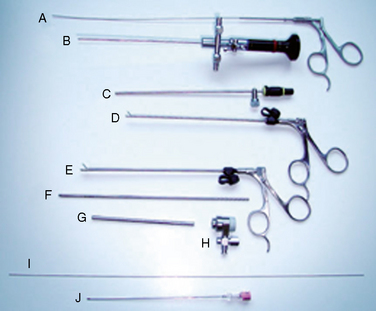

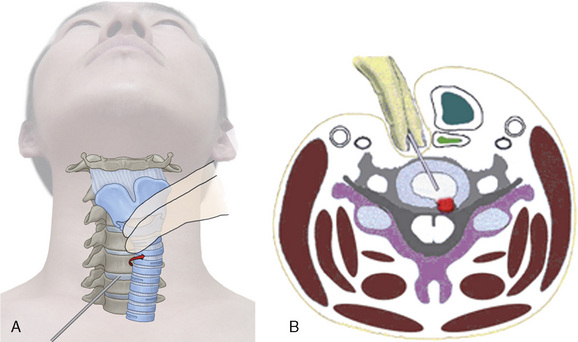

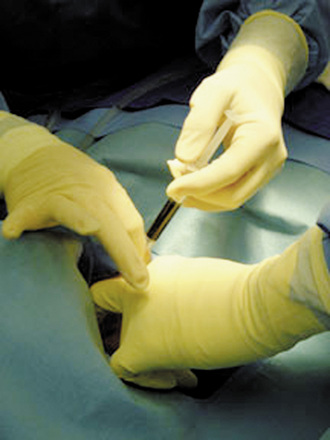

The majority of the anterior minimally invasive cervical discectomy procedures are based on small anterior anulotomy with cannula supported instrumentation, fluoroscopy and often endoscopy assisted intradiscal positioning. Then mechanical as well as laser or radiofrequency assisted disc removal and anular modulation is often added. Chiu and colleagues [5] substantiated their pursuit of minimally invasive cervical discectomy by stating that “fusion caused local inflammation, pain at the graft donor site, and a long recuperation compared to minimally invasive surgery without fusion which negates these complications.” As early as 1994, Chiu [6] had reported on 400 patients with nonextruded cervical disc herniations who had been treated with cervical endoscopic discectomy and laser thermodiscoplasty. With careful selection of patients and the use of lasers and microendoscopic equipment, a near 95% success rate was achieved. Table 21.1 shows the details of the international multicenter patient grouping treated with AECD [7].

The reduction in operative time, cost, and recuperation time with similar if not better outcomes and decrease in the need for fusion have indeed been successful at bringing minimally invasive cervical spine surgery to the 21st century. The commonplace use of lasers in spine surgery has also been a beneficial component of discectomy procedures. Prior to the use of lasers, an assortment of instruments were used with little or no side effects but none was able to satisfactorily remove the posterior disc and the displaced or herniated nuclear material [8]. In Korea, Lee began using holmium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Ho:YAG) laser with soft cervical disc herniations as early as 1993. His technique utilized the laser to remove the nucleus pulposus and to shrink down the protruded disc herniation in patients who had not experienced improvement with conservative therapy. It was noted at this time that the added benefit of the minimally invasive surgery was that it could be performed with use of local anesthesia, making monitoring of neurologic function readily evident. In 2001, Lee [8] wrote an article confirming his success with the percutaneous discectomy, stating that the combination of manual disc removal techniques with endoscopically directed Ho:YAG laser discectomy was a safe and effective surgical procedure.

Chemonucleolysis, the use of intradiscal chymopapain, has been out of favor in the United State for a number of years now. However, some surgeons have combined the use of low-dose chemonucleolysis with endoscopic discectomy procedures. In 1995, Hoogland and Scheckenbach [9] in Germany reported a new anterior cervical discectomy procedure with no complications. They performed low-dose chemonucleolysis utilizing 500 IU chymopapain followed by automated percutaneous nucleotomy of the cervical spine. The use of chymopapain remains quite limited, although the results of its use in association with minimally invasive surgery does seem to be improving. The use of lasers in this fashion is becoming more prominent, and with regard to the U.S. markets, lasers seemed to be more accepted than intradiscal chymopapain.

Procedure

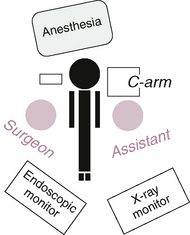

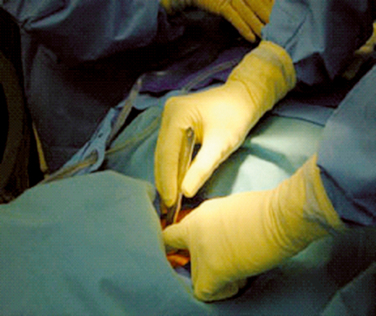

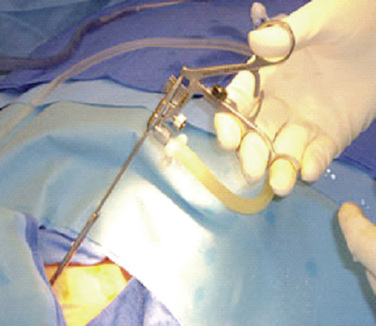

The operating room setup for AECD requires a radiolucent table, a C-arm (fluoroscope), and radiographic and endoscopic monitors, as shown in Figure 21-4. General anesthesia with intraoperative spinal monitoring is used. The patient is then placed in the supine position with a cervical roll for gentle neck extension and the arms at the sides with gentle wrist traction. After mechanical disc decompression, 800 to 1200 kilojoules total with the Ho:YAG laser or radiofrequency delivery with a Disc-FX System (Elliquence, LLC, Oceanside, NY) is used to modulate the injured posterior anulus so as to encourage stabilizing tissue ingrowth. Careful consideration is given to avoiding collapse with excessive tissue modulation.

Related anatomy and physiology

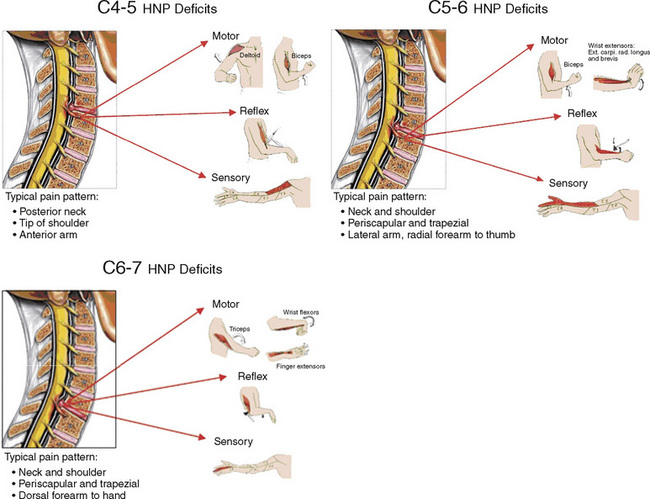

Figure 21-18 illustrates the most common clinical presentations of cervical herniated nucleus pulposus, the indication for AECD.

Postprocedural management

A case series has evaluated the minimally invasive anterior cervical discectomy technique without fusion since 1998 in the author’s practice [10]. The 349 patients identified—142 men, 207 women (average age 41.5)—had mostly soft disc herniations. A strengthening program involving the MedX Cervical Extension Machine (MedX Medical, Orlando, FL) after discectomy was also utilized. From April 2002 to April 2003, 21 patients received platelet gel after initial or revision discectomy compared with 56 patients who did not [10]. Platelet gel was developed in the early 1990s as a byproduct of multicomponent pheresis that, when combined with thrombin and calcium, rapidly forms a viscous coagulum (gel). Intraoperatively derived from 150 mL of whole blood using a cell-saver device, platelet gel has high concentrations of autologous growth factors that facilitate wound healing [11]. Table 21.2 depicts the comparative results during the same time period, which suggest the benefit of autologous platelet gel after discectomy.

Table 21.2 Results of the Use of Platelet Gel after Discectomy

| Patient Group | Rate of Good or Excellent Results (%) |

|---|---|

| 21 patients receiving platelet gel | 95 |

| 56 patients not receiving platelet gel | 87.50 |

Data from Wigfield CC, Nelson RJ. Nonautologous interbody fusion materials in cervical spine surgery: How strong is the evidence to justify their use? Spine 2001;26:687-694.

Complications

CASE STUDY 21.1

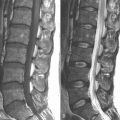

The patient is a 39-year-old white woman who was referred for a second opinion evaluation after sustaining a neck injury in a motor vehicle accident 6 months before. She had experienced worsening rather than improvement in symptomatology over that time. She had been seen by a number of physicians who recommended multiple courses of intervention, including physical therapy, multifaceted medical management, and even surgical reconstruction with open fusion. The cervical magnetic resonance imaging evaluation identified disc herniation at C5-C6 with additional disc bulging from C3 through C7 as seen in Figure 21-19.

Figure 21–19 Case Study 21.1: Magnetic resonance images showing disc herniation at C5-C6 (A) with additional level disc bulging from C3 through C7 (B).

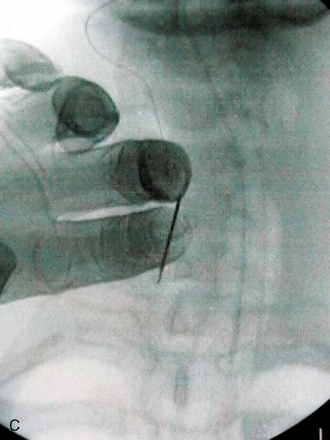

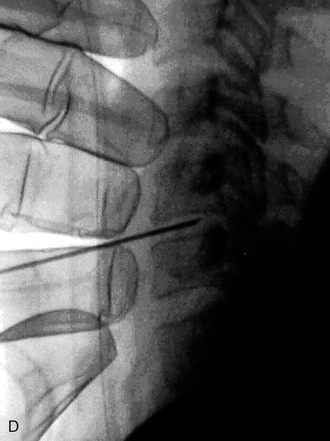

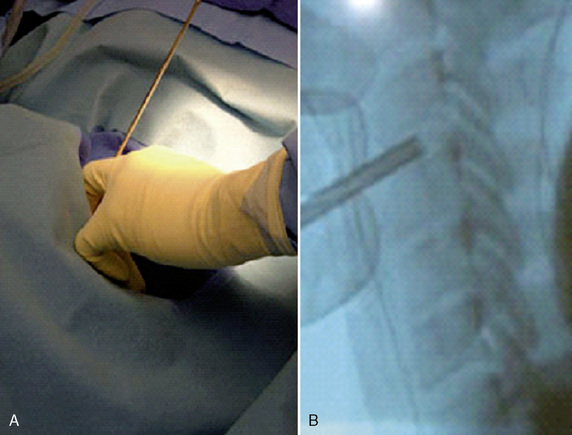

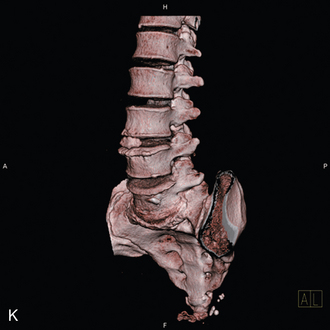

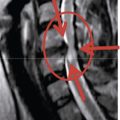

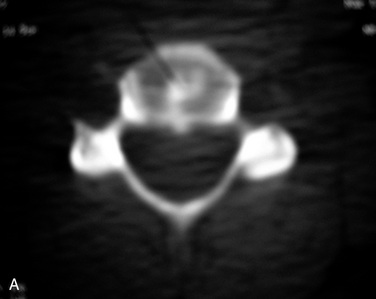

Because of the multilevel nature of the magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities, a discogram was performed to confirm symptomatology at C5-C6. Concordant pain elicited was with epidural leak at the C5-C6 level and no leak, and no pain was elicited at the adjacent levels. Figure 21-20 shows the fluoroscopic and post-injection computed tomographic images of the discogram study. It was decided to proceed with AECD at C5-C6.

Figure 21–20 Case Study 21.1: Post-injection computed tomographic (A) and fluoroscopic (B) images from the discogram study.

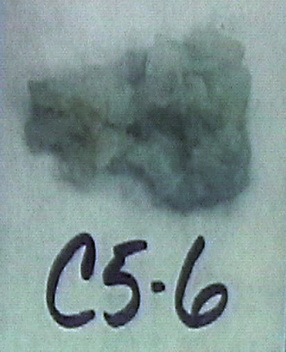

Figure 21-17 shows the removed disc material sent for gross inspection. The patient did well intraoperatively. Postoperatively, a firm Philadelphia collar was placed, and once the stitch was removed, the patient was told to utilize the soft collar at night for a total of 2 weeks.

Then, 4 weeks of soft collar use during the day during the subsequent rehabilitative program was instituted. The patient worked on extension range of motion and modalities during this time. At 4 weeks, she progressed to a MedX extension strengthening program for 4 more weeks. (Figure 21-21 depicts the use of the MedX cervical extension strengthening machine.) The patient gained significant relief of the arm pain shortly after the surgery, and the neck pain diminished over the subsequent 2 months with progressive rehabilitative therapy.

Figure 21–21 Case Study 21.1: MedX Cervical Extension Machine (MedX Medical, Orlando, FL), which the patient in 4-week strengthening program.

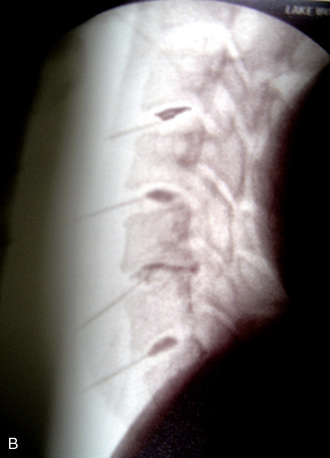

Slight disc space narrowing was evident on radiography at 3 months, although the patient had minimal cervical complaints at that time. Figure 21-22 shows the lateral cervical radiographs obtained before and 3 month after surgery, demonstrating the slight postoperative disc space narrowing at C5-C6. At 1 year, the patient was evaluated for some increase in low back pain, but no significant neck pain was identified.

Future directions

Cervical disc disease is an almost universal finding with human aging, and cervical disc injury and degeneration are the most common cause of cervical cord and nerve root dysfunction. Over the past century, significant strides have been made in identifying and treating these conditions. The standard procedure in the United States today remains the anterior cervical decompression with interbody fusion. It is estimated that more than 125,000 cervical spine fusions are performed in the United States alone each year [10].

1 Elsberg C.A. The extradural ventral chondromas (ecchondroses), their favorite sites, the spinal cord and root symptoms they produce, and their surgical treatment. Bull Neurol Inst NY. 1931;1:350-388.

2 Hilibrand A.S., Carlson G.D., Palumbo M.A., et al. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81-A:519-528.

3 Elsberg C.A. Tumors of the Spinal Cord and the Symptoms of Irritation and Compression of the Spinal Cord and Nerve Roots: Pathology, Symptomatology, Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: PB Hoeber, 1925;421.

4 Stookey B. Compression of spinal cord and nerve roots by herniation of the nucleus pulposus in the cervical regions. Arch Surg. 1940;40:417-432.

5 Chiu J.C., Clifford T.J., Reuter M.W. Cervical endoscopic discectomy with laser thermodiskoplasty. In: Savitz M.H., Chiu J.C., Yeung A.T., editors. The Practice of Minimally Invasive Spinal Technique. Richmond, VA: AAMISMS Education, LLC; 2000:141-148.

6 Chiu J.C., Hansraj K.K., Akiyama C., Greenspan M. Percutaneous (endoscopic) decompression discectomy for non-extruded cervical herniated nucleus pulposus. Surg Technol Int. 1997;6:405-411.

7 Chiu J.C. Multicenter Study of Percutaneous Endoscopic Discectomy (Lumbar, Cervical and Thoracic). Presented at the World Spine II: Second Interdisciplinary Congress on Spine Care. Chicago, IL; 2003 August 10–13

8 Lee S.H. Percutaneous cervical discectomy with forceps and endoscopic Ho:YAG laser. In: Gerber B.E., Knight M., Siebert W.E., editors. Lasers in the Musculoskeletal System. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001:292-302.

9 Hoogland T., Scheckenbach C. Low-dose chemonucleolysis with percutaneous nucleotomy in herniated cervical disks. J Spinal Disord. 1995;8:228-232.

10 Wigfield C.C., Nelson R.J. Nonautologous interbody fusion materials in cervical spine surgery: How strong is the evidence to justify their use? Spine. 2001;26:687-694.

11 London Perfusion Science product website. Available at http://www.londonperfusionscience.com