Chapter 60 Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction of Partial Tears

Reconstructing One Bundle

Introduction

It has been estimated that approximately 60,000 to 75,000 anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions are performed annually in the United States.1 This number is likely higher, as larger segments of the population have become active and participate in year-round sporting activities within the past several years. Outcomes of ACL reconstructions have been exhaustively studied, with many reports demonstrating successful return to sport and returning stability to the previously injured knee, particularly when compared with conservative management.2,3 Despite tremendous advances within the field of ACL reconstruction, success rates of primary reconstruction continue to hover between 70% to 95% within the best centers.4–6 With the increasing numbers of ACL being performed come the requisite number of cases that fail due to any variety of mechanisms: arthrofibrosis, extensor mechanism failure, recurrent patholaxity, and traumatic arthrosis.7 Several studies have demonstrated inferior results of revision surgery when compared with primary reconstruction, with many of these studies citing recurrent laxity as the primary mechanism of failure.8–12

The concept of recurrent laxity following a partial ACL injury or of a failed ACL reconstruction (with an intact, well-placed graft) can be treated within the same context. Both scenarios represent the same underlying anatomical defect: an isolated injury or absence of one of the bundles of the ACL that compromises the ability of the knee to achieve stability and normal kinematics. Most ACL injuries are currently treated with reconstruction of the anteromedial (AM) bundle of the ACL. Recurrent laxity within this situation can be classified as recurrent tear of the graft, continued instability despite graft incorporation and healing with proper graft placement, and improper placement of the graft leading to continued laxity. Recurrent laxity after isolated partial ACL tears can be from isolated injury to the posterolateral (PL) or AM bundles that results in the inability of the knee to resist either rotatory or translational forces.13 Our technique of isolated PL or AM augmentation surgery has evolved from this foundation of applying anatomical principles of the ACL with the anatomical injury or failure pattern. This chapter outlines our technique for isolated PL bundle augmentation surgery within the setting of recurrent patholaxity after prior ACL reconstruction (and a healed, well-placed ACL graft) as well as after partial ACL disruption (isolated PL bundle injury). Please see Chapter 25 for a more detailed description of the ACL anatomy and double-bundle reconstruction technique.

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

We obtain plain radiographs in all patients to look for associated pathology. These radiographs include bilateral anteroposterior (AP) flexion weight-bearing views, a lateral view of the involved knee, and bilateral merchant or sunrise views. The radiographs are inspected for soft tissue swelling, an effusion, the presence of any fractures, physeal closure (for younger patients), and overall alignment. In patients who have undergone prior ACL reconstruction, the prior tunnel placement is evaluated as well as prior hardware placement and presence of tunnel expansion. Determination of joint space narrowing is paramount in determining prognosis, and any patient who demonstrates any evidence of arthrosis on the knee series is further evaluated with a long cassette to determine alignment. If significant side-to-side difference exists (greater than 3–5 degrees) on the alignment series, consideration is given to a realignment procedure to unload the affected compartment. We obtain a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in any patient suspected of having a partial ACL tear or continued laxity after prior single-bundle ACL reconstruction. The MRI is also useful to inspect for the presence of any meniscal or chondral pathology. Reviewing the MRI with an experienced radiologist is often necessary to accurately make the diagnosis and properly plan for surgical intervention. Studies have shown that MRI diagnosis of partial ACL tears can be challenging.14,15 In one series, nine of nine complete tears were accurately diagnosed by MRI, whereas only 1 of 9 partial tears were correctly identified.14 Findings that were suggestive of partial ACL tears in this series were the presence of some intact fibers, thinning of the ligament, a mass posterolateral to the ACL, and a wavy or curved ligament. The MRI is inspected for the presence of a bone contusion, as this usually indicates a more severe injury. One study demonstrated that only 12% of patients with a partial tear of the ACL had a bone contusion in comparison to 72% with complete tears.16

Surgical Technique

Surgical Landmarks and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

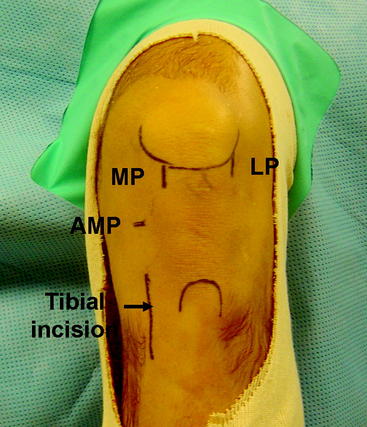

The knee is slightly flexed to 45 degrees, and the anatomical landmarks are identified. The inferior pole of the patella is drawn as well as the tibial tubercle. The borders of the patellar tendon and the anterior crest and posteromedial border of the tibia are identified. Three portholes are marked on the knee in the same fashion as in the double-bundle technique. The lateral porthole is located just off the lateral border of the patellar tendon with its most inferior border flush with the inferior border of the patella. The medial porthole is marked beginning at the inferior pole of the patella and extending distally just on the medial border of the patellar tendon. An accessory medial porthole that will later be used for the PL tunnel is marked approximately 2 cm medial to the AM porthole just at the level of the joint line. The tibial incision is marked on the AM aspect of the tibia midway between the anterior and posterior borders of the tibia. This incision is approximately 3 cm in length, beginning 2 cm distal to the medial joint line (Fig. 60-1).

Graft Preparation

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the graft is prepared by the surgical assistant on the back table. We prefer to use a looped tibialis anterior allograft for this procedure because the width and length of the graft are predictable. The graft is trimmed so that, when looped over, it will fit snugly into a 7-mm tunnel. A #2 braided suture is whipstitched up and down both ends of the graft for approximately 3 cm. Using a graft of at least 24 cm in total length will provide a looped graft of 12 cm, which is sufficient graft for the reconstruction. Once doubled over, the graft is secured via a loop to the Endobutton (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) device. Two sutures are then passed through the Endobutton device for later graft passage. An absorbable suture is used to suture the graft closed around the loop that secures the Endobutton. The graft is marked at two sites on its proximal end, one line indicating the tunnel length and the other indicating where the Endobutton can be flipped for femoral fixation (Fig. 60-2). The graft is then washed with antibiotic solution and placed in a moistened sponge until it will be used during the procedure.

Technique for Reconstruction

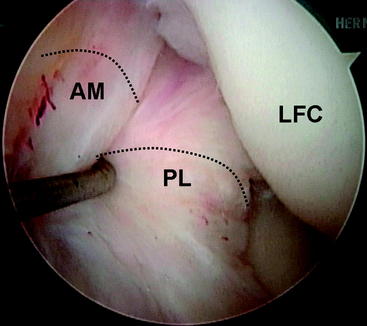

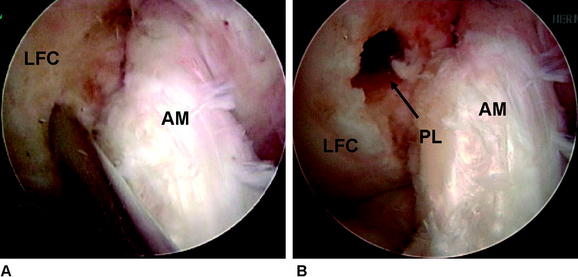

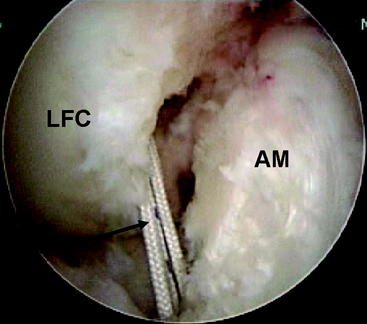

During the diagnostic examination, the femoral site of the PL bundle is marked with the thermal device where the fibers are avulsed. Knowledge of the origin of the ACL bundles on the LFC is paramount if no fibers of the ACL are remaining (Fig. 60-3). In the absence of this landmark (as in chronic cases or augmentation of a prior single-bundle reconstruction), general guidelines for the PL insertion are a point 8 mm posterior to the anterior articular margin of the lateral femoral condyle and 5 mm superior to the inferior articular margin of the LFC. A  -mm Steinman pin is introduced from the medial accessory porthole directly to this point. For optimal visualization, the arthroscope can be inserted into the medial porthole during preparation of the femoral tunnel (Fig. 60-4). The pin is tapped gently into the LFC to obtain initial purchase, and then the knee is flexed to approximately 115 to 120 degrees and the pin is sunk 5 to 10 mm into the condyle. The acorn reamer (7 mm) is then placed over the Steinman pin through the accessory medial porthole, and the femoral tunnel is drilled to a depth of 25 mm. The far cortex is then breached with the Endobutton drill, and the transcondylar length is measured with a depth gauge. If this length is greater than 35 mm, the tunnel is reamed an additional 5 mm for a total length of 30 mm. The tunnel length is then subtracted from the transcondylar length to determine the appropriately sized Endobutton, which is then fashioned to the graft by the surgical assistant.

-mm Steinman pin is introduced from the medial accessory porthole directly to this point. For optimal visualization, the arthroscope can be inserted into the medial porthole during preparation of the femoral tunnel (Fig. 60-4). The pin is tapped gently into the LFC to obtain initial purchase, and then the knee is flexed to approximately 115 to 120 degrees and the pin is sunk 5 to 10 mm into the condyle. The acorn reamer (7 mm) is then placed over the Steinman pin through the accessory medial porthole, and the femoral tunnel is drilled to a depth of 25 mm. The far cortex is then breached with the Endobutton drill, and the transcondylar length is measured with a depth gauge. If this length is greater than 35 mm, the tunnel is reamed an additional 5 mm for a total length of 30 mm. The tunnel length is then subtracted from the transcondylar length to determine the appropriately sized Endobutton, which is then fashioned to the graft by the surgical assistant.

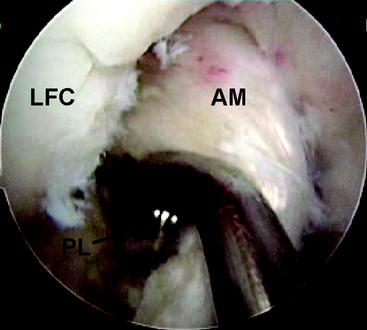

Attention is now turned to the tibial tunnel. It is paramount during this procedure that the tibial insertion of the PL bundle is accurately obtained so that the AM bundle is not compromised in any fashion. An incision is carried out based on our previous landmark, and the periosteum of the anteromedial tibia is exposed. The PL tibial insertion is identified at a site just medial to the attachment of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and slightly anterior to the PCL. The ACL director guide (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) is brought through the medial porthole and placed at this insertion site, set to 55 degrees. We prefer to use the direct “tip-to-tip” guide for accurate placement of the tunnel because the margin for error in this region is small. A  -mm Steinman pin is drilled through this guide on the AM surface of the tibia (typically slightly medial to the halfway point of the anterior and posterior borders of the tibia). The pin is drilled so that the tip is visible within the joint. A curette is used to prevent overpenetration in this region (Fig. 60-5). The PL tibial tunnel is then reamed to a diameter of 7 mm, and debris is removed with a full-radius resector. The PL tunnel should avoid the AM footprint entirely and be almost obscured from view by the fibers of the AM bundle.

-mm Steinman pin is drilled through this guide on the AM surface of the tibia (typically slightly medial to the halfway point of the anterior and posterior borders of the tibia). The pin is drilled so that the tip is visible within the joint. A curette is used to prevent overpenetration in this region (Fig. 60-5). The PL tibial tunnel is then reamed to a diameter of 7 mm, and debris is removed with a full-radius resector. The PL tunnel should avoid the AM footprint entirely and be almost obscured from view by the fibers of the AM bundle.

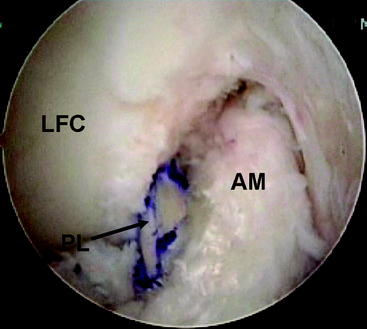

A Beath pin with a large looped suture on its distal end is then introduced through the accessory medial porthole and fashioned through the PL femoral tunnel out through the lateral aspect of the thigh. Care is taken to hyperflex the knee and retract the biceps manually to prevent injury to the common peroneal nerve with this maneuver. The looped suture is then brought into the joint and obtained via a suture grasper through the tibial PL tunnel. The sutures attached to the Endobutton are then fashioned through the loop, and the sutures are shuttled to the lateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 60-6). The graft is then passed in standard fashion and the Endobutton loop is flipped, providing femoral fixation (Fig. 60-7). The knee is then cycled from 0 to 120 degrees 20 times while holding tension on the tibial side to check for isometry and remove any slack within the allograft tissue. The PL bundle is then tensioned between 0 and 10 degrees with a biointerference screw measuring 7 × 30 mm. This fixation is augmented with a small staple on the AM aspect of the tibia with the remainder of the allograft. The knee is then checked for stability and range of motion.

Rehabilitation

The patient is placed in a hinged knee brace that is locked in extension for 1 week. Crutches are used for 4 to 6 weeks until quadriceps function returns. The brace is unlocked only for continuous passive motion (CPM) and range of motion during the first week. The patient is weight bearing as tolerated, barring any concomitant meniscal repair. The accelerated rehabilitation protocol as described by Irrgang is then followed.17 Return to sports is typically allowed after 6 months, provided adequate strength gains have been achieved. All patients are advised to use a functional knee brace when returning to sports during the first 1 to 2 years after reconstruction.

Conclusion

Several studies have documented the natural history of partial tears of the ACL. Despite some early encouraging results, the majority of patients never return to their pre-injury level of activity or sport.18,19 In a study by Barrack et al, more than 30% of patients had fair or poor results at the latest follow-up.20 Noyes et al followed 32 patients with partial ACL tears and found that 12 went on to complete rupture.21 Buckley et al found that 72% of partial ACL tears had activity related symptoms at early follow-up.22 With these disappointing results, combined with the residual instability that occasionally compromises patients who have had a prior ACL reconstruction, we believe that augmentation surgery may offer a more definitive solution.

1 Johnson DL, Harner CD, Maday MG, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Fu FH, Harner CD, Vince KG, editors. Techniques in Knee Surgery. vol 1. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:877-895.

2 Grontvedt T, Engebretsen L, Benum P, et al. A prospective, randomized study of three operations for acute rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. Five-year follow-up of one hundred and thirty-one patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:159-168.

3 Sandberg R, Balkfors B, Nilsson B, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of recent injuries to the ligaments of the knee. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69A:1120-1126.

4 Howell SM, Clark JA. Tibial tunnel placement in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions and graft impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;283:187-195.

5 Jaureguito JW, Paulos LE. Why grafts fail. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;325:25-41.

6 Ritchie JR, Parker RD. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament revision surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;325:65-77.

7 Newhouse KE, Paulos LE. Complications of knee ligament surgery. In: Nicholas JA, Hershman EB, editors. The lower extremity and spine in sports medicine. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:901-908.

8 Getelman MH, Friedman MJ. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:189-198.

9 Uribe JW, Hechtman KS, Zvijac JE, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: experience from Miami. CORE. 1996;325:91-99.

10 Johnson DL, Swenson TM, Irrgang JJ, et al. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: experience from Pittsburgh. CORE. 1996;325:100-109.

11 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: experience from Cincinnati. CORE. 1996;325:116-129.

12 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery with use of bone-patellar tendon-bone autogenous grafts. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83A:1131-1143.

13 Gabriel MT, Wong EK, Woo SL-Y, et al. Distribuition of in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament in response to rotatory loads. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:85-89.

14 Lawrance JA, Ostlere SJ, Dodd CA. MRI diagnosis of partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Injury. 1996;27:153-155.

15 Umans H, Wimpfheimer O, Haramati N, et al. Diagnosis of partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee: value of MR imaging. Am J Radiol. 1995;165:893-897.

16 Zeiss J, Paley K, Murray K, et al. Comparison of bone contusion seen by MRI in partial and complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:773-776.

17 Irrgang JJ. Modern trends in anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: nonoperative and postoperative management. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:797-813.

18 Bak K, Scavenius M, Hansen S, et al. Isolated partial rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. Long-term follow-up of 56 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:66-71.

19 Sommerlath K, Odensten M, Lysholm J. The late course of acute partial anterior cruciate ligament tears. A nine to 15-year follow-up evaluation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;281:152-158.

20 Barrack RL, Buckley SL, Bruckner JD. Partial versus complete acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. The results of nonoperative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72B:622-624.

21 Noyes FR, Mooar LA, Moorman CTIII, et al. Partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Progression to complete ligament deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:825-833.

22 Buckley SL, Barrack RL, Alexander AH. The natural history of conservatively treated partial anterior cruciate ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:221-225.