Chapter 63 Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Combined with High-Tibial Osteotomy, Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation, Microfracture, Osteochondral, and/or Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

Success Rates

In the literature and in our experience, success rates with appropriate combined procedures have been high. Table 63-1 summarizes the relevant literature. Surgery and aftercare must be meticulous. Reimbursement may not be commensurate with the amount of work performed. Not all surgeons will wish to perform these types of procedures. However, if the procedures are satisfactorily performed, and if the patients are carefully chosen, the results can be gratifying.

| Author | Year | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|

| ACLR with OATS | ||

| Klinger20 | 2003 | 81% normal or nearly normal on IKDC |

| Bobic21 | 1996 | 10/12 patients had promising response at 2-year follow-up |

| ACLR with ACI | ||

| Amin8 | 2006 | 7/9 patients improved; 2/9 described no improvement |

| ACLR with MAT | ||

| Graf12 | 2004 | 1/8 patients had nearly normal results; 7/8 had abnormal or severely abnormal on IKDC scale |

| Sekiya11 | 2003 | 86% normal or nearly normal on IKDC |

| Yoldas14 | 2003 | 19/20 reported normal or nearly normal on IKDC |

| Wirth15 | 2002 | Recorded substantial improvement in both Lysholm and Tegner scores |

| Rath16 | 2001 | Significantly reduced pain and increase function (SF-36) |

| Cameron17 | 1997 | 80% of patients who had ACLR + MAT had good-excellent results; 86% of those who had ACLR, MAT, and HTO had good to excellent results |

| ACLR with HTO | ||

| Williams24 | 2003 | Found statistically significant increases in Lysholm, HSS, Tegner score; 92% of patients were satisfied |

| Noyes25 | 2000 | Pain was reduced in 71% of knees; 71% of patients reported their knees as very good/normal or good |

| Stutz26 | 1996 | 8/13 patients had normal or nearly normal subjective IKDC scores |

| Lattermann29 | 1996 | 3/8 patients had pain even with light activity |

| Neuschwander27 | 1993 | 4/5 patients had good or excellent result; one had fair |

| Noyes25 | 1993 | 94% of patients reported significant improvement |

ACI, Autologous chondrocyte implantation; ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; HSS, Hospital for Special Surgery; HTO, high-tibial osteotomy; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; MAT, meniscal allograft transplantation; OATS, osteochondral autograft transfer system.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Microfracture

Microfracture has been shown to be an effective procedure for generating a fibrocartilaginous fill for full-thickness articular cartilage defects.1–3 It can easily be performed together with ACLR and should be performed simultaneously whenever possible to save the patient an extra and unnecessary anesthetic. The 6-week postoperative period of touchdown weight bearing that is required after microfracture (MF) does not adversely affect the ACLR. It is important only to make sure that good passive range of motion (ROM) is achieved. Decreased activity after ACLR has actually been associated with less tunnel widening in one study.4 For those who believe in aggressive strengthening immediately after ACLR, this regimen will seem restrictive. However, in the long term there should be no adverse effect. We have not found the addition of ACLR to adversely affect the expected good results after microfractures. There is no 2-year follow-up literature on ACLR with microfracture of which we are aware. However, our clinical experience has been favorable with lesions less than 2 cm. We have found larger lesions to not fare as well and in earlier years had to revise several microfractures to autologous chondrocyte implantations (ACI). Although the ultimate results in those cases were good, in recent years we have proceeded directly to ACI when encountering lesions greater than 2 cm.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantations

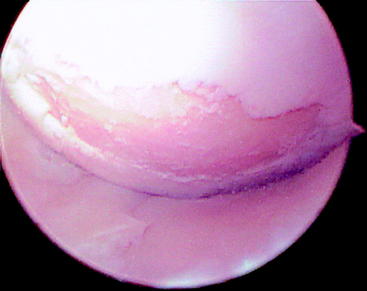

ACI5–7 is the first procedure that has successfully generated hyaline-like cartilage in full-thickness articular cartilage defects. It is usually not carried out simultaneously with ACLR because the ACLR is usually performed before the need for ACI has been discovered. Thus the articular cartilage biopsy (ACB), rather than the ACI, is usually performed at the time of the ACLR. Generally the ACI will be performed as a staged subsequent procedure. If the lesion is on the femoral condyles, as opposed to the trochlea, we prefer to wait 4 to 6 months before performing ACI after ACLR. The reason is that ACI can involve hyperflexion of the knee to sew to the posterior aspect of many lesions. This hyperflexion will stress the graft, and we prefer not to subject newly implanted grafts to this stress. During the revascularization phase in the first few months postoperatively, grafts are severely weakened and are subject to plastic deformation if stressed. Trochlear grafts are implanted without hyperflexion and thus are safe early after ACLR. Allograft ACL grafts may need to be protected longer. If ACI and ACLR are performed simultaneously, the more restrictive ACI protocol needs to be adopted. This should not adversely affect the ACLR results. In general it is not advisable to perform ACI before ACLR because a stable knee is considered necessary for successful ACI. Also, this type of sequencing would require three procedures because the ACB needs to precede the ACI. However, in cases when the ACB has been performed prior to the ACLR, the ACI and ACLR may then be carried out simultaneously at a subsequent procedure. Good results have been reported after the combined procedures.8 Young patients with acute lesions, such as the 17-year-old girl shown in Fig. 63-1, are ideal candidates. Older patients with acute lesions can also obtain excellent results with ACLR and ACI, such as was the case with a 53-year-old woman who tore her ACL while snow skiing (Fig. 63-2). When the ACL tear is somewhat chronic even in a young patient, such as the 27-year-old woman with a failed ACLR performed at age 20 (Fig. 63-3), early degenerative changes can make treatment more difficult.

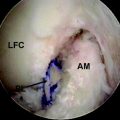

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Meniscal Allograft Implantation

Meniscal allograft implantation (MAT) has been associated with generally high success rates.9–11 There is some risk in performing MAT simultaneously with ACLR because there is a propensity in some knees for stiffness after MAT. Crowding also occurs between the tibial tunnel for the ACLR and the trough for lateral MAT as well as the bone tunnel(s) for medial MAT. However, if these are the only two procedures necessary and if the surgeon has sufficient experience with both procedures, then it is possible to perform them simultaneously to save the patient the discomfort of a second procedure. The rehabilitation protocols are compatible, and avoidance of stiffness needs to be prioritized by using appropriately aggressive rehabilitation. If the ACLR is performed first, we prefer to wait 4 to 6 months before performing the MAT to allow the graft to mature as described in the section on ACLR and ACI. In theory, MAT should not performed before ACLR because a stable knee is a prerequisite for the performance of MAT. However, MAT followed within a few months by ACLR should not subject the graft to undue stress because the patient will not be vigorously active during this period. Indeed, if the procedures are staged it may be technically easier to perform the ACLR second because the MAT will be more easily performed in the knee with greater laxity before the ACLR.12–17 The patient whose radiographs are shown in Fig. 63-4 had severe pain and was unable to perform his job as a federal law enforcement agent at 38 years of age, 16 years after ACL tear and meniscectomy. He underwent high-tibial osteotomy (HTO) with substantial improvement. ACLR was then performed with further improvement but with residual medial pain still persisting. MAT was then performed, leading to almost complete resolution of symptoms 1 year after surgery. These procedures allowed him to resume his career, including his 1-mile-run test, without pain.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Osteochondral Allograft or Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System

Osteochondral autograft transfer system (OATS)18 and osteochondral allograft (OCAI)19 are widely used procedures. Either can be performed simultaneously with ACLR if the surgeon has sufficient experience. They can also be performed sequentially before or after ACLR. The literature has shown good results.20,21

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and High-Tibial Osteotomy

HTO has shown good results over many decades of use.22,23 Numerous newer reports show good results after combined ACLR and HTO,24–28 although the complication rate can be significant.29 This combination also entails a potentially greater risk of stiffness relative to the other combined procedures. The reason is that all osteotomies, regardless of the surgical technique used, are somewhat unstable in the first few months postoperatively. Thus if the ACLR/HTO surgery does result in significant stiffness, it is harder to treat because aggressive mobilization of the knee cannot be performed in the first few months post-HTO due to the risk of displacing the osteotomy, even if rigid internal fixation is used. This is also somewhat dependent on the HTO technique used. Techniques performed above the tibial tubercle involve the periarticular structures. These HTO procedures add their own propensity to stiffness to that of the ACLR. Procedures performed below the tibial tubercle should involve less such risk. The surgeon must therefore assess the risks attendant to both the ACLR and HTO procedures as best as possible and decide whether there is excessive risk in performing both procedures simultaneously. We perform a bone transport osteotomy below the tubercle using an external fixator and no hardware, which has little risk of stiffness. Our hamstring ACLR procedure has also had excellent ROM results.30 However, some ACLRs have required aggressive rehabilitation to regain full extension. Even though the number is small, it is difficult to predict with which knees this will occur. HTO patients often have some degree of medial arthrosis. These knees are also somewhat predisposed to stiffness.

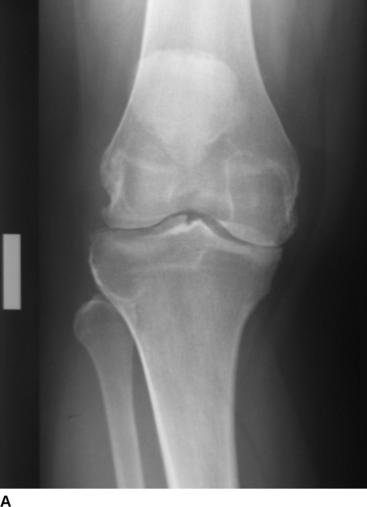

HTO procedures are not without complications, and these patients must be operated on carefully and followed closely. Most, however, have a smooth course. Fig. 63-5 shows a patient 8 months after simultaneous ACLR and HTO. The osteotomy is well healed. The tibial fixation screw for the ACL graft can be seen proximal to the osteotomy. The medial joint space on these standing views shows increased cartilage space in the postoperative radiograph compared with preoperatively.

Conclusions

1 Gill TJ. The role of the microfracture technique in the treatment of full-thickness chondral injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2000;8:138-140.

2 Gobbi A, Nunag P, Malinowski K. Treatment of full thickness chondral lesions of the knee with microfracture in a group of athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:213-221.

3 Miller BS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, et al. Patient satisfaction and outcome after microfracture of the degenerative knee. J Knee Surg. 2004;17:13-17.

4 Hantes ME, Mastrokalos DS, Yu J, et al. The effect of early motion on tibial tunnel widening after anterior cruciate ligament replacement using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:572-580.

5 Bentley G, Biant LC, Carrington WJ, et al. A prospective, randomised comparison of autologous chondrocyte implantation versus mosaicplasty for osteochondral defects in the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85:223-230.

6 Minas T, Chiu R. Autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13:41-50.

7 Peterson L, Minas T, Brittberg M, et al. Two- to 9-year outcome after autologous chondrocyte transplantation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;374:212-234.

8 Amin AA, Bartlett W, Gooding CR, et al. The use of autologous chondrocyte implantation following and combined with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Int Orthop. 2006;30:48-53.

9 Fukushima K, Adachi N, Lee JY, Moore GG. Meniscus allograft transplantation using posterior peripheral suture technique: a preliminary follow-up study. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9:235-241.

10 Ryu RKN, Dunbar WH, et al. Meniscal allograft replacement: a 1-year to 6-year experience. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:989-994.

11 Sekiya JK, Giffin JR, Irrgang JJ, et al. Clinical outcomes after combined meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:896-906.

12 Graf KWJr, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM. Long-term results after combined medial meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: minimum 8.5-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:129-140.

13 Sekiya JK, Giffin JR, Irrgang JJ, et al. Clinical outcomes after combined meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:896-906.

14 Yoldas EA, Sekiya JK, Irrgang JJ, et al. Arthroscopically assisted meniscal allograft transplantation with and without combined anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:173-182.

15 Wirth CJ, Peters G, Milachowski KA, et al. Long-term results of meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:174-181.

16 Rath E, Richmond JC, Yassir W, et al. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Two- to eight-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:410-414.

17 Cameron JC, Saha S. Meniscal allograft transplantation for unicompartmental arthritis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;337:164-171.

18 Gudas R, Stankevicius E, Monastyreckiene E, et al. Osteochondral autologous transplantation versus microfracture for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in the knee joint in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:834-842.

19 Aubin PP, Cheak HK, Davis AM, et al. Long-term followup of fresh femoral osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;391S:S318-S327.

20 Klinger HM, Baums MH, Otte S, et al. Anterior cruciate reconstruction combined with autologous osteochondral transplantation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:366-371.

21 Bobic V. Arthroscopic osteochondral autograft transplantation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a preliminary clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;3:262-264.

22 Koshino T, Wada S, Ara Y, Saito T. Regeneration of degenerated articular cartilage after high tibial valgus osteotomy for medial compartmental osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee. 2003;10:229-236.

23 Sprenger TR, Doerzbacher JF. Tibial osteotomy for the treatment of varus gonarthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:469-474.

24 Williams RJIII, Kelly BT, Wickiewicz TL, et al. The short-term outcome of surgical treatment for painful varus arthritis in association with chronic ACL deficiency. J Knee Surg. 2003;16:9-16.

25 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Hewett TE. High tibial osteotomy and ligament reconstruction for varus angulated anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:282-296.

26 Stutz G, Boss A, Gachter A. Comparison of augmented and non-augmented anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction combined with high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:143-148.

27 Neuschwander DC, Drez DJr, Paine RM. Simultaneous high tibial osteotomy and ACL reconstruction for combined genu varum and symptomatic ACL tear. Orthopedics. 1993;16:679-684.

28 Noyes FR, Barber SD, Simon R. High tibial osteotomy and ligament reconstruction in varus angulated, anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees. A two- to seven-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:2-12.

29 Lattermann C, Jakob RP. High tibial osteotomy alone or combined with ligament reconstruction in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:32-38.

30 Prodromos CC, Han YS, Keller BL, et al. Stability of hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at two- to eight-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:138-146.