6

Anterior Chamber

Primary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Definition

Glaucoma due to obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by peripheral iris; classified as acute, subacute (intermittent), or chronic.

Etiology/mechanism

Pupillary Block

Most common. Lens–iris apposition interferes with aqueous flow and causes the iris to bow forward and occlude the trabecular meshwork.

Plateau Iris Syndrome (Without Pupillary Block)

Peripheral iris occludes the angle in patients with an atypical iris configuration (anteriorly positioned peripheral iris with steep insertion due to anteriorly rotated ciliary processes) (see Chapter 7).

Epidemiology

Approximately 5% of the general population over 60 years old have occludable angles, 0.5% of these develop angle-closure. Usually bilateral (develops in 50% of untreated fellow eyes within 5 years); higher incidence in Asians and Eskimos; female predilection (4 : 1). Associated with hyperopia, nanophthalmos, anterior chamber depth less than 2.5 mm, thicker lens, and lens subluxation.

Symptoms

Acute Angle-Closure

Pain, red eye, photophobia, decreased or blurred vision, halos around lights, headache, nausea, emesis.

Subacute Angle-Closure

May be asymptomatic or have symptoms of acute form but less severe; episodes evolve over the course of days or weeks and resolve spontaneously.

Chronic Angle-Closure

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or constricted visual fields in late stages.

Signs

Acute Angle-Closure

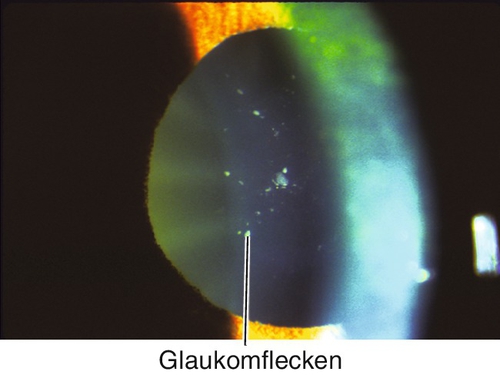

Decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, ciliary injection, corneal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare, shallow anterior chamber, narrow angles on gonioscopy, mid-dilated nonreactive pupil, iris bombé; may have signs of previous attacks including sector iris atrophy, anterior subcapsular lens opacities (glaukomflecken; due to lens epithelial cell ischemia and necrosis from high intraocular pressure), dilated irregular pupil, and peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS).

Subacute and Chronic Angle-Closure

Narrow angles; may have increased intraocular pressure, PAS, sector iris atrophy, glaukomflecken, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Consider provocative testing (prone test, dark room test, prone dark room test, and pharmacologic dilation; intraocular pressure increase of >8 mmHg is considered positive).

Prognosis

Good if prompt treatment is initiated for acute attack; poorer for chronic cases but depends on extent of optic nerve damage and subsequent intraocular pressure control.

Secondary Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Definition

Acute or chronic angle-closure glaucoma caused by a variety of ocular disorders.

Etiology/mechanism

With Pupillary Block

Lens-induced (phacomorphic, dislocated lens, microspherophakia), seclusio pupillae, aphakic or pseudophakic pupillary block, silicone oil, nanophthalmos.

Without Pupillary Block

Posterior “pushing” mechanism

Mechanical or anterior displacement of the lens–iris diaphragm.

• Anterior rotation of ciliary body due to:

• Inflammation (scleritis, uveitis, panretinal photocoagulation).

• Congestion (scleral buckling, nanophthalmos).

• Choroidal effusion (hypotony, uveal effusion, medication [topiramate, sulfonamides]).

• Suprachoroidal hemorrhage.

• Aqueous misdirection (malignant glaucoma).

• Pressure from posterior segment (tumor, expanding gas, exudative retinal detachment).

• Developmental abnormalities (persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, retinopathy of prematurity).

Anterior “pulling” mechanism

Adherence of iris to the trabecular meshwork or membranes over the trabecular meshwork.

• Epithelial (downgrowth or ingrowth).

• Endothelial (iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, posterior polymorphous dystrophy).

• Neovascular (neovascular glaucoma; see Chapter 7).

• Postinflammatory peripheral anterior synechiae.

• Adhesion from trauma.

• Mesodermal dysgenesis syndromes.

Symptoms

Acute Angle-Closure

Pain, red eye, photophobia, decreased or blurred vision, halos around lights, headache, nausea, emesis.

Chronic Angle-Closure

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or constricted visual fields in late stages.

Signs

Acute Angle-Closure

Decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, ciliary injection, corneal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare, shallow anterior chamber, narrow angles on gonioscopy, mid-dilated nonreactive pupil, iris bombé; signs of underlying etiology.

Chronic Angle-Closure

Narrow angles, increased intraocular pressure, PAS, signs of underlying etiology; may have sector iris atrophy, glaukomflecken, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

Prognosis

Poorer than primary angle-closure because usually due to chronic process; depends on etiology, extent of optic nerve damage, and subsequent intraocular pressure control.

Hypotony

Definition

Low intraocular pressure (≤ 5 mmHg).

Etiology

Increased Outflow (Excessive Drainage of Aqueous or Vitreous Fluid)

Trauma (cyclodialysis), surgery (wound leak, bleb overfiltration), choroidal effusion, retinal detachment.

Decreased Production (Ciliary Body Shutdown)

Inflammation (uveitis), medication (ciliary body toxicity: 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin-C, cidofovir, mannitol, anesthetic agents [fentanyl, succinylcholine, propofol, sevoflurane]), systemic disorder (bilateral hypotony: dehydration, ketoacidosis, uremia), cyclitic membrane, anterior proliferative vitreoretinopathy, ocular ischemic syndrome, phthisis.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have pain and decreased vision.

Signs

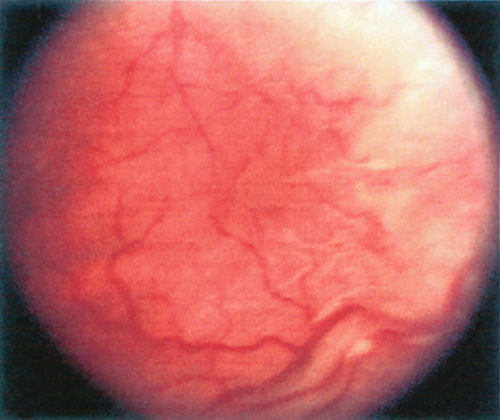

Normal or decreased visual acuity, low intraocular pressure, functional and structural changes usually occur; may have refractive (hyperopic) shift, corneal folds and edema, positive Seidel test, filtering bleb, anterior chamber cells and flare, shallow anterior chamber, cyclodialysis cleft, cataract, cyclitic membrane, choroidal effusion, chorioretinal folds (hypotony maculopathy), cystoid macular edema, retinal detachment, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, optic disc edema, phthisis (end-stage; see Chapter 1).

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to cornea, tonometry, anterior chamber, gonioscopy, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Seidel test (see Trauma: Laceration section in Chapter 5) to rule out open globe or wound leak in traumatic or postsurgical cases.

• B-scan ultrasonography to evaluate choroidal effusion, retinal detachment, and intraocular foreign body if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) to identify cyclitic membrane, cyclodialysis cleft, and ciliary body detachment (≥ 2 clock hours).

• Consider fluorescein angiogram or OCT to identify choroidal folds.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology and duration.

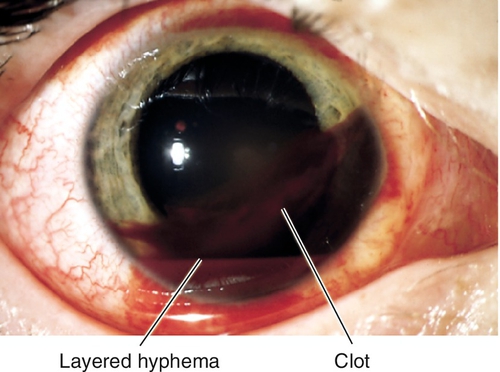

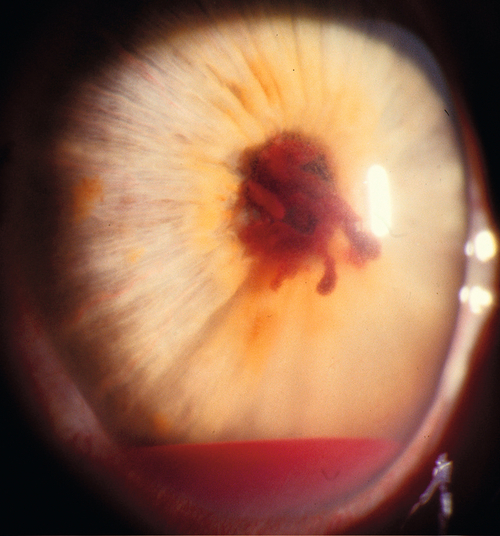

Hyphema

Definition

Blood in the anterior chamber. Hyphema forms a layer of blood, whereas a microhyphema cannot be visualized with the naked eye (can only see red blood cells floating in the anterior chamber on slit-lamp examination).

Etiology

Usually traumatic (60% also have angle recession); may be spontaneous when associated with neovascularization of the iris or angle, iris lesions, or a malpositioned or loose intraocular lens (IOL).

Symptoms

Decreased vision; may have pain, photophobia, red eye.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, red blood cells in the anterior chamber (layer or clot); may have subconjunctival hemorrhage, increased intraocular pressure, rubeosis, iris sphincter tears, unusually deep anterior chamber, angle recession, iridodonesis, iridodialysis, cyclodialysis, and other signs of ocular trauma; may have iris lesion or pseudophacodonesis of IOL implant.

Differential Diagnosis

Trauma, uveitis–glaucoma–hyphema (UGH) syndrome, juvenile xanthogranuloma, leukemia, child abuse, postoperative, Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis, rubeosis irides.

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography to rule out open globe if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider UBM to evaluate angle structures.

• Lab tests: Sickle cell prep and hemoglobin electrophoresis to rule out sickle cell disease.

Prognosis

Good in traumatic cases if intraocular pressure is controlled and there is no rebleed; may be at risk for angle recession glaucoma in the future.

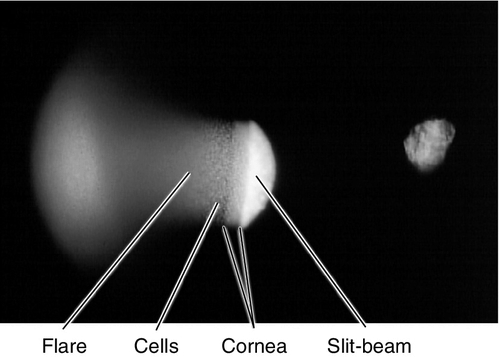

Cells and Flare

Definition

Extravasated leukocytes (cells) and protein and fibrin (flare) in the anterior chamber due to breakdown of the blood–aqueous barrier by inflammation.

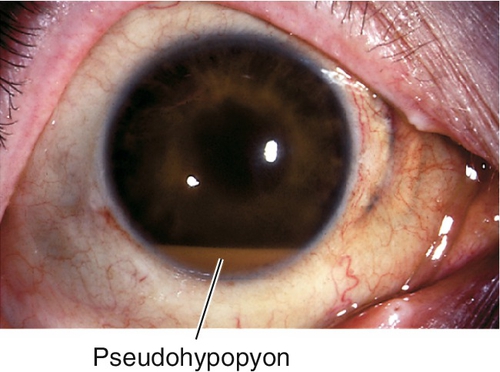

Cells

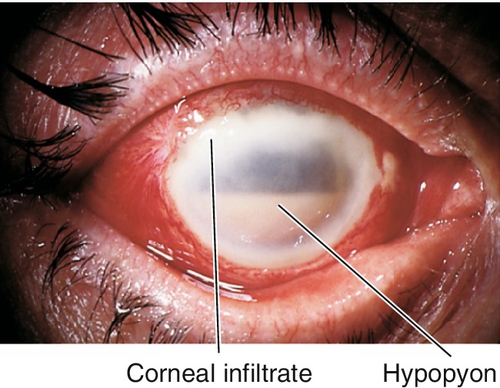

Appear as small white particles floating in the aqueous. Other types of cells can sometimes be present in the aqueous: red blood cells (microhyphema), pigment cells (from iris after dilation and in pigment dispersion syndrome), and tumor cells. Large quantities of cells can settle inferiorly in the anterior chamber and form a layer (hypopyon [WBCs], hyphema [RBCs], or pseudohypopyon [pigment, ghost, or tumor cells]).

Flare

Appears as hazy or cloudy aqueous; severe fibrinous exudate produces a jelly-like plasmoid aqueous appearance with strands of fibrin (4+ flare).

Etiology

Exudation from blood vessels due to anterior segment inflammation; usually uveitis, trauma, postoperative, scleritis, and keratitis.

Symptoms

Variable pain, photophobia, tearing, red eye, decreased vision; may be asymptomatic.

Signs

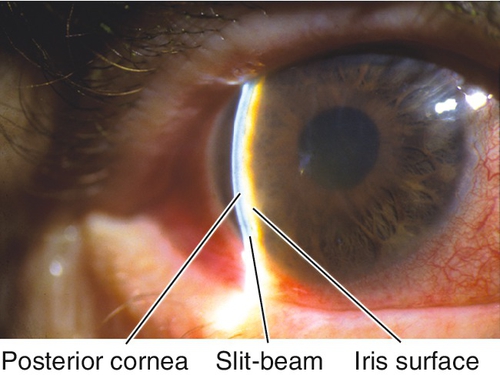

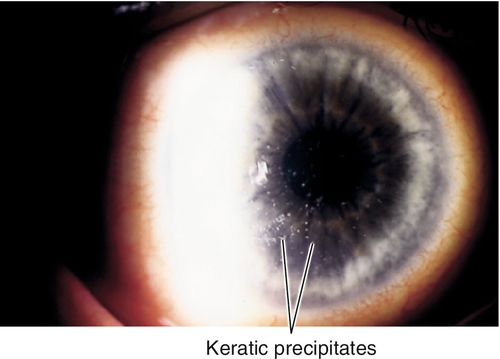

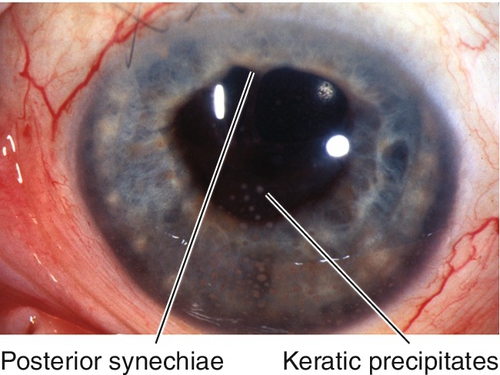

Normal or decreased visual acuity, ciliary injection, miosis, anterior chamber cells and flare (best seen when viewed with a short narrow (1 × 1 mm) slit-lamp beam directed at a 30–45° angle through the pupil producing an effect similar to shining a flashlight through a dark room; cells demonstrate brownian motion and flare looks like smoke in the light beam; graded on a 0 to 4 scale [i.e., Cells: 0 = 0 cells; 1+ = 5–10 cells; 2+ = 11–20 cells; 3+ = 21–50 cells; 4+ = > 50 cells; often trace or minimal refers to 1–4 cells. Flare: 0 = empty; 1+ = faint; 2+ = moderate (iris / lens clear); 3+ = marked (iris / lens hazy); 4+ = severe (fibrin, fixed aqueous, no motion of cells [termed fibrinoid or “plastic” anterior chamber reaction]).]) May have scleritis, keratic precipitates, keratitis, iris nodules, posterior synechiae, increased or decreased intraocular pressure, hypopyon, hyphema, pseudohypopyon, cataract, vitritis, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal or choroidal lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

See above.

Evaluation

• Consider uveitis workup (see Anterior Uveitis section).

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

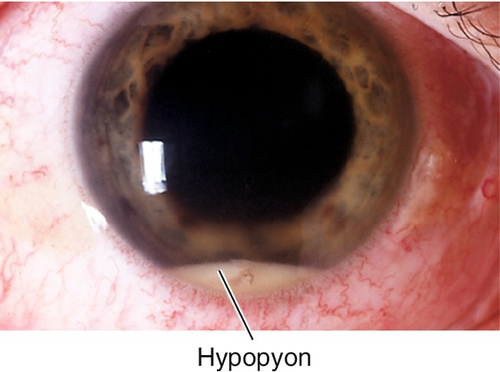

Hypopyon

Definition

Layer of white blood cells in the anterior chamber.

Etiology

Usually due to inflammation (uveitis, especially HLA-B27 associated and Behçet’s disease) or infection (corneal ulcer, endophthalmitis).

Symptoms

Pain, red eye, and decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, hypopyon, and anterior chamber cells and flare; may have scleritis, corneal infiltrate, keratic precipitates, iris nodules, cataract, vitritis, or retinal or choroidal lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudohypopyon (layer of other cells in the anterior chamber including pigment cells, ghost cells, tumor cells, or macrophages).

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Lab tests: Cultures and smears for infectious keratitis (see Chapter 5) or endophthalmitis (see Endophthalmitis section).

• Consider uveitis workup (see Anterior Uveitis section).

Prognosis

Depends on etiology and treatment response.

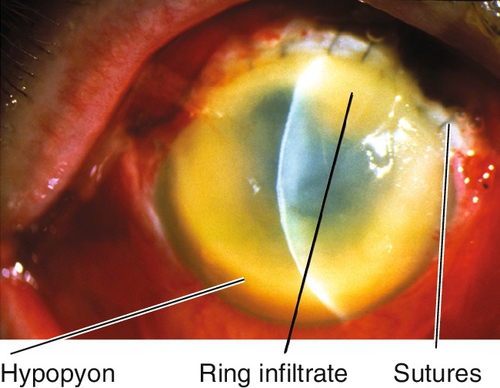

Endophthalmitis

Definition

Intraocular infection; may be acute, subacute, or chronic; localized or involving anterior and posterior segments.

Etiology

Postoperative (70%)

Acute postoperative (< 6 weeks after surgery)

Ninety-four percent Gram-positive bacteria including coagulase-negative staphylococci (70%), Staphylococcus aureus (10%), Streptococcus spp. (11%); only 6% Gram-negative organisms.

Delayed postoperative (> 6 weeks after surgery)

Propionibacterium acnes, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and fungi (Candida spp.).

Conjunctival filtering bleb associated

Streptococcus spp. (47%), coagulase-negative staphylococci (22%), Haemophilus influenzae (16%).

Posttraumatic (20%)

Bacillus (B. cereus) spp. (24%), Staphylococcus spp. (39%), and Gram-negative organisms (7%).

Endogenous (2–15%)

Rare, usually fungal (Candida spp.); bacterial endogenous is usually due to S. aureus and Gram-negative bacteria. Occurs in debilitated, septicemic, or immunocompromised patients, especially after surgical procedures.

Epidemiology

Incidence following cataract surgery is less than 0.1%; risk factors include loss of vitreous, disrupted posterior capsule, poor wound closure, and prolonged surgery. Incidence following penetrating trauma is 4–13%, may be as high as 30% after injuries in rural settings; risk factors include retained intraocular foreign body, delayed surgery (> 24 hours), rural setting (soil contamination), disrupted crystalline lens.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, discharge, red eye, decreased vision; may be asymptomatic or have chronic uveitis appearance in delayed onset and endogenous cases.

Signs

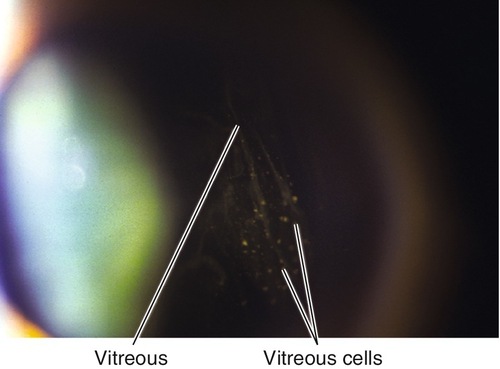

Decreased visual acuity (usually severe; only 14% of patients in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS) had better than 5 / 200 vision), lid edema, proptosis, conjunctival injection, chemosis, wound abscess, corneal edema, keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells and flare, hypopyon, vitritis, poor red reflex; may have positive Seidel test and other signs of an open globe (see Chapter 4).

Differential Diagnosis

Uveitis, sterile inflammation (usually from prolonged intraoperative manipulations, especially involving vitreous; retained lens material; rebound inflammation after sudden decrease in postoperative steroids; or toxic anterior segment syndrome [TASS; acute postoperative anterior chamber reaction and corneal edema due to contaminants from surgical instruments, intraocular solutions, or intraocular lens (IOL) implant]), blebitis (infection of filtering bleb), intraocular foreign body, intraocular tumor, sympathetic ophthalmia, anterior segment ischemia (from carotid artery disease [ocular ischemic syndrome] or following muscle surgery [usually on three or more rectus muscles in same eye at the same surgery]).

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history with attention to surgery and trauma.

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, conjunctiva, sclera, cornea, tonometry, anterior chamber, vitreous cells, red reflex, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Seidel test (see Trauma: Laceration section in Chapter 5) to rule out wound leak or open globe in postsurgical or traumatic cases.

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Lab tests: STAT evaluation of intraocular fluid cultures and smears; conjunctival and nasal swabs can also be collected for culture but have low yield.

• Medical consultation for endogenous endophthalmitis.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology, duration, and organism; usually poor, especially for traumatic cases.

Anterior Uveitis (Iritis, Iridocyclitis)

Definition

Inflammation of the anterior uvea (iris [iritis] and ciliary body [cyclitis]) with exudation of white blood cells and protein into the anterior chamber secondary to breakdown of the blood–aqueous barrier and increased vascular permeability from a variety of disorders. Minimal spill-over into the retrolental space can be present. Classified by pathology (nongranulomatous [lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrates] or granulomatous [epithelioid and giant cell infiltrates]), location (keratouveitis, sclerouveitis, anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, endophthalmitis, panuveitis), course (acute, chronic, recurrent), or etiology.

Etiology

Most commonly idiopathic or associated with HLA-B27, but it is critical to rule out other causes such as infection, malignancy, medication, and trauma.

Infectious Anterior Uveitis

Herpes Simplex and Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

Acute or chronic, recurrent iritis, especially herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO); often with keratic precipitates underlying areas of dendritic or stromal keratitis; elevated intraocular pressure common; may have sector iris atrophy, corneal scarring, and decreased corneal sensation.

Lyme Disease

Patients have classic cutaneous erythema chronicum migrans at the site of a tick bite; due to Borrelia burgdorferi transmitted by Ixodes dammini or I. pacificus tick; 1–3 months later can develop neurologic involvement including encephalitis and meningitis. In addition to iritis, may also have conjunctivitis, keratitis, vitritis, and optic neuritis; may develop chronic skin changes, chronic arthritis, and cardiac manifestations.

Syphilis

Chronic or recurrent nongranulomatous or granulomatous anterior uveitis can be an ocular manifestation of acquired secondary syphilis; may also have interstitial keratitis, dilated iris vascular tufts (iris roseola), vitritis, chorioretinitis, papillitis, and mucocutaneous manifestations (see Chapters 5 and 10). This infection must be ruled out in every patient with persistent iritis, because systemic antibiotics are necessary to prevent significant morbidity.

Tuberculosis

Chronic granulomatous iritis; may also have conjunctival nodules, phlyctenules, interstitial keratitis, scleritis, iris nodules, vitritis, and choroiditis (see Chapter 10). It is rarely caused by direct ocular infection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and most of the time is an immune response directed toward the organism. Patients with a chronic granulomatous iritis who are immunocompromised or come from endemic areas should be evaluated for tuberculosis.

Noninfectious Anterior Uveitis

Nongranulomatous

Idiopathic (acute)

Most common cause of anterior uveitis (50%).

HLA-B27 associated (acute)

Recurrent iritis with alternating involvement of both eyes (~ 75%), usually severe inflammation with fibrinoid anterior chamber reaction, posterior synechiae, and hypopyon. Accounts for up to 50% of anterior uveitis; often male (3 : 1) and tend to develop iritis as young or middle-aged adults; may be chronic or bilateral in women and children; distinct entity from the idiopathic form. Up to 90% have or develop signs related to a seronegative spondyloarthropathy.

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies (acute)

Group of conditions sharing common features that include: radiographic sacroiliitis (with or without spondylitis), asymmetric peripheral arthritis without rheumatoid nodules, negative rheumatoid factor (RF) and antinuclear antibody (ANA), HLA-B27 association, variable mucocutaneous lesions, and anterior uveitis.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Thirty percent develop anterior uveitis, recurrent in 40%, also episcleritis and scleritis. Patients develop lower back pain and stiffness after inactivity; also associated with aortitis and pulmonary apical fibrosis; arthritis less severe in women, but eye disease can still be severe. Sacroiliac radiographs often show sclerosis and narrowing of joint spaces; untreated patients will progress to debilitating spinal fusion; 90% have positive HLA-B27 test results.

Reiter’s syndrome (reactive arthritis)

Triad of nonspecific urethritis, polyarthritis (80%), and mucopurulent, papillary conjunctivitis with iritis; arthritis starts within 30 days of infection; also associated with keratoderma blennorrhagicum, circinate balanitis, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, sacroiliitis, palate or tongue ulcers, nail pitting, prostatitis, and cystitis. Occurs in males age 15–40 years old (90%); may be triggered by diarrhea or infectious organism (Chlamydia, Ureaplasma, Yersinia, Shigella, Salmonella); 85–95% have positive HLA-B27 test results.

Inflammatory bowel disease

In contrast to the unilateral iritis associated with ankylosing spondylitis and Reiter’s syndrome, the iritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease is usually bilateral and has a posterior component; may also develop dry eyes, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, orbital cellulitis, and optic neuritis. Occurs in 5–10% of patients with ulcerative colitis, more common in Crohn’s disease; associated with sacroiliitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, hepatitis, and sclerosing cholangitis; 60% of patients with sacroiliitis have positive HLA-B27 test results.

Psoriatic arthritis

Twenty percent develop iritis; also conjunctivitis and dry eyes. Patients have “sausage” digits from terminal phalangeal joint arthritic involvement, subungual hyperkeratosis, erythematous rash, nail pitting, and onycholysis; associated with sacroiliitis; iritis rarely occurs when psoriasis appears without arthritis; associated with HLA-B27.

Whipple’s disease

Rare systemic disorder associated with Tropheryma whippelii infection, characterized by chronic diarrhea (due to malabsorption), joint inflammation, central nervous system manifestations, and anterior uveitis; associated with sacroiliitis, spondylitis, and HLA-B27.

Behçet’s disease (acute)

Triad of recurrent hypopyon iritis, aphthous stomatitis, and genital ulcers; also develop arthritis, thromboembolism, and central nervous system problems; iritis is usually bilateral with posterior involvement, the hallmark is occlusive retinal vasculitis (see Chapter 10). More common in Asians and Middle Easterners; associated with HLA-B5 (subtypes Bw51 and B52) and HLA-B12.

Glaucomatocyclitic crisis (Posner–Schlossman syndrome) (acute)

Unilateral, mild, recurrent iritis with markedly elevated intraocular pressure, corneal edema, fine keratic precipitates, and a mid-dilated pupil; no synechiae; self-limited episodes (hours to days); associated with HLA-Bw54.

Kawasaki’s disease (acute)

Exanthematous disease with bilateral conjunctivitis and anterior uveitis in children (see Chapter 4); may be fatal.

Drugs (acute)

Certain medications may cause anterior uveitis, specifically rifabutin, cidofovir, sulfonamides, bisphosphonates, diethylcarbamazine, and metipranolol.

Interstitial nephritis (acute)

Usually bilateral, anterior uveitis that occurs more frequently in children, may have posterior involvement; female predilection. Patients have fever, malaise, arthralgias; urinalysis shows white blood cells without infection. May be due to allergic reaction to a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory or antibiotic; can progress to renal failure if not treated with oral steroids.

Other autoimmune disease (acute and chronic)

Systemic lupus erythematosus, relapsing polychondritis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA, acute and chronic)

Most common cause of uveitis in children, typically bilateral, anterior uveitis with minimal redness and pain. Type I is pauciarticular (90%), RF negative, ANA positive, female predilection (4 : 1), no sacroiliitis, and earlier onset (by age 4 years); type II is pauciarticular, RF negative, ANA negative, HLA-B27 positive, male predilection, sacroiliitis common, and later onset (by age 8 years); both have a chronic course with poor prognosis. Another subset is childhood spondyloarthropathy, which causes an acute, unilateral, self-limited, anterior uveitis; usually in males, older than 12 years, and HLA-B27 positive. Iritis is rare in polyarticular RF-negative JRA and Still’s disease.

Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis (chronic)

Accounts for 2% of anterior uveitis. Usually unilateral (90%), low-grade iritis with small, white, stellate keratic precipitates, abnormal anterior chamber angle vessels (friable and bleed easily with rapid surgical lowering of intraocular pressure [i.e., during paracentesis]), diffuse iris atrophy may cause heterochromia (for lightly pigmented irides involved iris appears darker; for darkly pigmented irides involved iris appears lighter), and no synechiae; predilection for blue-eyed patients; associated with glaucoma (15%) and cataracts (70%). Good prognosis; poor response to topical steroids (therefore, not indicated).

Postoperative or trauma (acute or chronic)

Ocular injury including surgery produces variable anterior chamber inflammation, and must be distinguished from: exacerbation of preexisting uveitis, TASS, retained lens fragments, UGH syndrome, endophthalmitis, and sympathetic ophthalmia.

Granulomatous

Autoimmune

Sarcoidosis (see Chapter 10), Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome (see Chapter 10), sympathetic ophthalmia (see Chapter 10), Wegener’s granulomatosis, multiple sclerosis, and lens-induced (phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis [phacoantigenic uveitis]; an immune-mediated [type 3] hypersensitivity reaction to lens particles after trauma or surgery causing a zonal granulomatous reaction after a latent period).

HLA associations (located on chromosome 6)

A29 Bird-shot retinochoroidopathy.

B5 Behçet’s disease (also B12).

B7 Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, serpiginous choroidopathy, ankylosing spondylitis.

B8 Sjögren’s syndrome.

B12 Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

B27 Ankylosing spondylitis (88%), Reiter’s syndrome (85–95%), inflammatory bowel disease (60%), psoriatic arthritis (also B17).

Bw54 Posner–Schlossman syndrome.

DR4 Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, tearing, red eye; may have decreased vision or floaters. JRA can produce severe anterior uveitis without significant pain or redness.

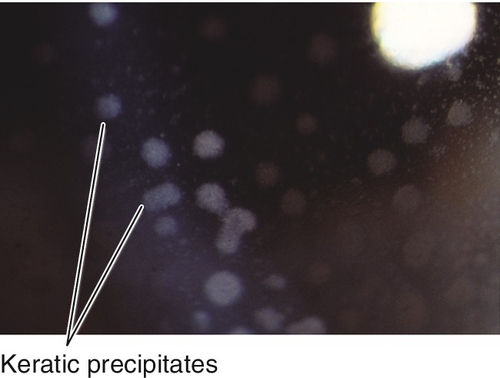

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, ciliary injection, miosis, anterior chamber cells and flare; may have fine (nongranulomatous) or mutton fat (granulomatous) keratic precipitates, keratitis, decreased corneal sensation, iris nodules (Koeppe, Busacca, Berlin; see Figures 7-42 and 7-43), iris atrophy, usually decreased intraocular pressure but may be increased (especially in HSV, HZV, Posner–Schlossman syndrome, sarcoidosis, toxoplasmosis), peripheral anterior synechiae, posterior synechiae, hypopyon (especially HLA-B27 associated and Behçet’s disease), cataract, vitritis, retinal or choroidal lesions, cystoid macular edema, optic disc edema.

Differential Diagnosis

Masquerade syndromes include retinal detachment, retinoblastoma, malignant melanoma, leukemia, large cell lymphoma (reticulum cell sarcoma), juvenile xanthogranuloma, intraocular foreign body, anterior segment ischemia, ocular ischemic syndrome, and spill-over syndromes from any posterior uveitis (most commonly toxoplasmosis) (see Chapter 10).

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to corneal sensation, character and location of keratic precipitates, tonometry, anterior chamber, iris (nodules and atrophy), vitreous cells, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Lab testing according to following general principles: Defer testing if first episode of mild, unilateral, nongranulomatous anterior uveitis not associated with systemic symptoms or signs suggestive of an underlying etiology (usually idiopathic), or if diagnosis is known.

• Basic testing recommended for nongranulomatous anterior uveitis with a negative history, review of systems, and medical examination: complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test or microhemagglutination for Treponema pallidum (MHA-TP) (syphilis), HLA-B27.

• Other lab tests that should be ordered according to history and / or evidence of granulomatous inflammation: ANA, RF (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), serum lysozyme, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (sarcoidosis), purified protein derivative (PPD) and controls (tuberculosis), herpes simplex and herpes zoster titers, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Lyme immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody test, chest radiographs (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis), chest CT scan (sarcoidosis), sacroiliac radiographs (ankylosing spondylitis), knee radiographs (JRA, Reiter’s syndrome), gallium scan (sarcoidosis), urinalysis (interstitial nephritis), and urethral cultures (Reiter’s syndrome).

• Special diagnostic lab tests: HLA typing, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) (Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa), Raji cell and C1q binding assays for circulating immune complexes (systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic vasculitides), complement proteins: C3, C4, total complement (systemic lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia, glomerulonephritis), soluble interleukin-2 receptor.

• Medical or rheumatology consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; usually good if inflammation controlled. Poor if sequelae of chronic inflammation exist including cataract, glaucoma, posterior synechiae, band keratopathy, iris atrophy, cystoid macular edema, retinal detachment, retinal vasculitis, optic neuritis, neovascularization, hypotony, phthisis.

Uveitis–Glaucoma–Hyphema Syndrome

Definition

Triad of findings in patients with closed-loop and rigid anterior chamber, iris-supported, or loose sulcus IOLs secondary to trauma to angle structures, iris, or ciliary body.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, red eye, and decreased vision; may have constricted visual fields in late stages.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, anterior chamber cells and flare, hyphema, IOL implant; may have corneal edema, optic nerve cupping, retinal nerve fiber layer defects, and visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

Neovascular glaucoma, trauma.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

Prognosis

Variable; depends on duration and extent of ocular damage; visual loss is permanent.