30

Antenatal care

Introduction

Most pregnancies are uneventful and uncomplicated and would progress normally without medical intervention. There are three main purposes to antenatal care: health promotion, preparation for labour and parenthood and surveillance of risk. The purpose of the latter is to provide appropriate surveillance for all pregnancies in the hope of identifying the small number that develop complications, with the aim of optimizing the outcomes for both the mother and her baby.

This should be achieved without unnecessary interference and tailored to the individual woman. Care is often based on a traditional arrangement of antenatal visits. The schedule varies, with the initial, or ‘booking’ visit, ideally between 8 and 10 weeks, with subsequent visits 4-weekly until 30 weeks; 2-weekly until 32 weeks and then weekly thereafter. There is debate about rearranging this care according to evidence-based practice, which indicates a less frequent attendance; the incentive for change from parents and care providers is often weak.

In western societies, antenatal care is provided by a variable combination of midwives, obstetricians and family doctors, depending on local preferences and resources. Care may be shared and may include some hospital visits and some more local visits to other practitioners, allowing the hospital to focus on those who need more intensive input. Some women will receive their antenatal care solely at home.

In the resource-poor countries, many mothers have little or no antenatal care. Access to healthcare is limited by poverty, lack of facilities, lack of education and cultural resistance.

The booking visit

The purpose of the antenatal booking visit is to detect any risk factors that may indicate the necessity of extra surveillance above that provided to ‘low-risk’ women. It is also an opportunity to identify any social difficulties and to discuss the parents’ own wishes for the pregnancy and delivery.

Past obstetric history

A detailed account of the previous pregnancies and labours should be obtained, including gestation at delivery and whether the labour was induced or of spontaneous onset. The duration of labour, mode of delivery, birth weight, sex, neonatal outcome and any postnatal complications should also be noted.

Women who have experienced obstetric difficulties in a previous pregnancy are often keen to talk these through and consider the likelihood of recurrence. This is frequently a listening exercise so that anxieties can be expressed, especially in cases of previous fetal or neonatal loss. An explanation followed by discussion of possible recurrence risks and a plan for the next pregnancy is useful.

Medical and surgical history

This should include details of previous operations, particularly gynaecological procedures, such as a previous excisional treatment to the cervix (may predispose to cervical incompetence), and include a history of whether blood transfusions have been received (possibility of having developed red cell antibodies). Questions should be asked about relevant medical disorders such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, renal disease, epilepsy, asthma or abnormal thyroid function.

Family history

The family history should enquire of potential inherited conditions such as thalassaemia, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anaemia and also chromosomal disorders and previous congenital structural abnormalities.

History of present pregnancy

The date of the first day of the last menstrual period and details of the menstrual cycle prior to conception should be noted. However, the expected due date is routinely calculated from gestational age assessment following ultrasound in the first half of pregnancy rather than from menstrual dates.

Social and drug history

It is essential to note all drugs and medications taken by the mother immediately prior to and during the pregnancy, as some preparations may be teratogenic. Alcohol, smoking and drug misuse should also be noted and discussed, with referral to appropriate support and/or cessation services. Evidence of socioeconomic deprivation is relevant, since women may require additional support during pregnancy. Identification of matters relating to child protection concerns necessitates referral to the social work department.

Mental health

It is important not to overlook depression or other mental health disorders. A history should be obtained of any previous mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or any previous postnatal depression or psychosis. A relevant family history or history of previous contact with mental healthcare services should be obtained. Depression should also be considered antenatally and questions can be asked at booking to identify possible depression. Appropriate referral to specialist antenatal support services can then be arranged to support the woman during her pregnancy.

Examination

A general examination is performed to include measurement of pulse rate, blood pressure, weight and height, the latter two used to calculate the body mass index (BMI). A BMI > 30 indicates an increased potential for pregnancy complications. Abdominal examination provides an approximate indication of the uterine size, and may rarely identify abnormal masses and other abnormalities. Vaginal examination is not routinely performed.

Ultrasound scan

This key investigation establishes fetal viability, gestational age and identifies multiple pregnancy when present. It is also an opportunity to measure the nuchal translucency (see p. 266) where appropriate and to diagnose some fetal anomalies, e.g. anencephaly.

Urine analysis

The urine is analysed for the presence of protein and glucose. In early pregnancy, proteinuria may be a sign of a urinary tract infection and glycosuria occasionally indicates hyperglycaemia.

Booking blood samples

![]() Full blood count to exclude maternal anaemia and thrombocytopenia (p. 222).

Full blood count to exclude maternal anaemia and thrombocytopenia (p. 222).

![]() Blood group to determine the ABO and rhesus status of the mother and to detect the presence of any red cell antibodies (p. 315).

Blood group to determine the ABO and rhesus status of the mother and to detect the presence of any red cell antibodies (p. 315).

![]() Rubella status to identify those mothers who are not immune to rubella and are therefore at risk of a primary rubella infection during pregnancy. Such women are offered rubella vaccination after delivery (p. 274).

Rubella status to identify those mothers who are not immune to rubella and are therefore at risk of a primary rubella infection during pregnancy. Such women are offered rubella vaccination after delivery (p. 274).

![]() Haemoglobin electrophoresis may be offered to all women, or restricted to those of certain ethnic origin, particularly those of Asian, Afro-Caribbean or Mediterranean origin, and will identify those mothers who may be carriers of sickle cell anaemia or thalassaemia.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis may be offered to all women, or restricted to those of certain ethnic origin, particularly those of Asian, Afro-Caribbean or Mediterranean origin, and will identify those mothers who may be carriers of sickle cell anaemia or thalassaemia.

![]() Hepatitis B status allows for counselling of the woman and her family together with neonatal vaccination if the result is positive.

Hepatitis B status allows for counselling of the woman and her family together with neonatal vaccination if the result is positive.

![]() Serological testing for syphilis. Those with positive tests should receive referral to a genitourinary medicine specialist and treatment with penicillin where appropriate.

Serological testing for syphilis. Those with positive tests should receive referral to a genitourinary medicine specialist and treatment with penicillin where appropriate.

![]() HIV (see p. 188).

HIV (see p. 188).

Screening discussion

It is essential to use the booking visit to discuss screening options for chromosomal and structural abnormalities. This is often an emotive area and parents should be made aware of the implications of any tests they accept or decline (see p. 266).

Nutritional supplements

All pregnant women should be offered folic acid for the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, as it reduces the risk of neural tube defects. Ideally, folic acid should be provided pre-conceptually. Vitamin D deficiency is becoming more common among pregnant women, giving rise to skeletal abnormalities such as rickets, in newborns. Women who are at risk of vitamin D deficiency include those who remain covered while outdoors; eat a diet low in vitamin D; have a BMI > 30 or are of South Asian, African, Caribbean or Middle Eastern origin. Appropriate vitamin D supplementation should be offered to these women during pregnancy. Routine iron supplementation is not required and should be reserved for specific indications, principally iron deficiency anaemia.

Health promotion

The antenatal period provides an ideal opportunity to provide health promotion information to women who might otherwise not interact with health services. Information should be provided in an accessible format and interpreter provision should be available as required. It is important to be mindful of cultural issues and to deal with these sensitively. For example, women who have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) may be reluctant to discuss this with a healthcare professional. However, by doing so, a plan of care can be discussed in preparation for birth.

Antenatal planning

Mothers at the extremes of reproductive age are at increased risk of obstetric complications, particularly hypertensive disorders, and they also have an increased risk of perinatal mortality.

The incidence of pre-eclampsia in a second pregnancy is 10–15 times greater if there was pre-eclampsia in the first pregnancy, compared with those with a normal first pregnancy, although pre-eclampsia tends to be less severe in subsequent pregnancies. Low-dose aspirin (75 mg once daily) taken from the first trimester and continued throughout pregnancy reduces the likelihood of recurrent pre-eclampsia.

Those who have had a previous instrumental delivery usually have an unassisted delivery next time around, but may occasionally request a planned caesarean section. Careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of such a request is required. In general, women with a previous caesarean section for a non-recurrent indication (the majority), e.g. breech, fetal distress or relative cephalopelvic disproportion secondary to fetal malposition should be offered vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC), although repeat elective caesarean section may be recommended in certain circumstances. With spontaneous onset of labour, women can be quoted an approximate 70% likelihood of achieving a vaginal birth when undertaking VBAC, with the principal risk of uterine rupture occurring in approximately 1 in 300. Women with uncomplicated pregnancies should be given information on different birth settings, including home, from which they can choose their preferred place of birth.

In situations where there has been previous fetal growth restriction or an intrauterine death (death of the fetus in utero after 24 weeks’ gestation), subsequent management depends on the cause and the estimated likelihood of recurrence. More intensive antenatal monitoring is usually offered and the outcome is usually good, particularly when the loss was ‘unexplained’.

Smoking during pregnancy is associated with fetal growth restriction and premature delivery. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk of placental abruption, intrauterine death and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol and illicit drug misuse, e.g. cocaine, carry significant fetal risks and these should be avoided in pregnancy.

Women whose work environment exposes them to radiation, hazardous gases or specific chemicals should be appropriately counselled. There is no evidence that video display units (VDUs) are harmful, or indeed that working during pregnancy itself is harmful to the mother or fetus. Moderate exercise is likely to be of benefit and should be encouraged, but common sense should be applied and exercise be avoided if there are significant complications such as hypertension, cardiorespiratory compromise, antepartum haemorrhage or threatened pre-term labour.

Antenatal surveillance

Subsequent visits are then used to identify obstetric complications; antenatal care is in the most part an exercise in screening both the mother and fetus.

Gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia

Blood pressure is measured and a urinalysis performed at each visit, and there should be a low threshold for acting on any abnormalities (see Chapter 36).

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) and small-for-gestational-age (SGA)

‘Small-for-gestational-age’ (see also Chapter 35) describes the fetus or baby whose estimated fetal weight or birth weight, respectively is below the tenth centile for its gestation, expressed in weeks. The term ‘fetal growth restriction’ describes ‘a fetus which fails to reach its genetic growth potential’. In practice, it may be difficult to differentiate the two antenatally, but fetal growth restriction carries a significant risk of antenatal and intrapartum asphyxia, intrauterine death, neonatal hypoglycaemia, long-term neurological impairment and perinatal death. It is therefore important to identify these fetuses at an early stage to enable more intensive monitoring or expedite delivery.

Screening for SGA is by clinical palpation and objective measurement of symphysis fundal height (SFH) with a tape measure; this identifies 40–50% of the babies that are SGA. It is recommended that symphysis fundal height should be measured every visit from 24 weeks onwards. Ultrasound fetal biometry is the diagnostic test for the SGA fetus. Routine screening of all pregnancies by third trimester ultrasound is not supported by currently published evidence.

Obesity

Women with a BMI ≥ 30 are at increased risk of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, caesarean section, induction of labour, wound infections, venous thromboembolism and anaesthetic complications. There is an increased risk of stillbirth, congenital abnormality, prematurity and macrosomia (birth weight 4.5 kg) in the infants of obese women. Antenatal surveillance should be modified with these risks in mind.

Impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes

Some centres offer a glucose tolerance test (GTT) to women who fulfill certain criteria, such as family history of diabetes, BMI ≥ 30, previous large-for-gestational-age baby or persistent glycosuria, while other centres screen all women by performing random blood sugar measurements and offering a GTT to those who are hyperglycaemic. The practice in part depends on the prevalence of the condition in the relevant population. The significance of a positive diagnosis is discussed further on page 253.

Haemolytic disease

Maternal IgG antibodies to fetal red cell antigens cross the placenta and may lead to fetal haemolysis, anaemia and hydrops fetalis. Initial sensitization usually occurs at the time of a previous delivery, but may also occur with vaginal bleeding during pregnancy, amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling, external cephalic version (recognized potentially sensitising events) or at some unrecognized event (silent feto-maternal transfusion). The most significant antibody is to the rhesus antigen, which rhesus-negative mothers may develop against rhesus-positive fetal cells. All women should be screened for anti-red cell antibodies at booking and again in the third trimester. Those with antibodies require further investigation (p. 315). Rhesus-negative women without sensitization (the vast majority) are routinely recommended to receive one or two doses of anti-D immunoglobulin in the third trimester in order to minimize the risk of sensitization from unrecognized feto-maternal transfusions. Anti-D is routinely advised following a recognized sensitizing event.

Breech presentation

The incidence of breech presentation is 25% at 32 weeks and 3% at term, with the chance of spontaneous version after 38 weeks being less than 4%. It is associated with multiple pregnancy, bicornuate uterus, fibroids, placenta praevia, polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios. Planned caesarean section at term is associated with less perinatal mortality and less serious neonatal morbidity than is planned vaginal birth, making it important for breech presentation to be identified prior to the onset of labour. This allows the option of external cephalic version and a more planned delivery.

Breech presentation can be suspected following clinical palpation and confirmed by ultrasound scan. For further management, see page 355.

Anaemia

Anaemia in pregnancy is defined as an haemoglobin (Hb) concentration < 10.5 g/dL. As there is a physiological fall in Hb as pregnancy advances, there is often uncertainty about the value of treating mild anaemia (e.g. Hb 9–10 g/dL). Iron supplements may lead to gastrointestinal side-effects and have no proven benefits in the absence of demonstrable iron deficiency. Most maternity units will recommend oral FeSO4 if the Hb is < 10 g/dL or if the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is low (< 80 fL), but it is advisable to estimate serum folate, vitamin B12 and ferritin before embarking on therapy. Oral iron is well absorbed and the only indication for parenteral iron is when there are concerns regarding compliance or there are prohibitive side-effects with oral supplements.

Polyhydramnios

In the second and third trimesters, amniotic fluid (liquor) is produced by the fetal kidneys and micturition, and is also swallowed by the fetus. Excess liquor, polyhydramnios, is suspected by clinical examination – the uterus feels tight, fetal parts are difficult to palpate and the symphysis fundal height is above the 90th centile for gestational age. Polyhydramnios is diagnosed with ultrasound and may be described by:

![]() a single pool > 8 cm in depth, and/or

a single pool > 8 cm in depth, and/or

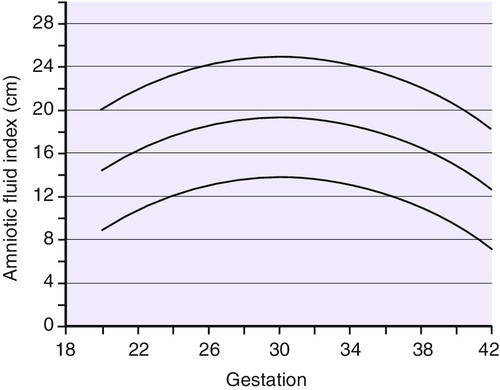

![]() an amniotic fluid index > 90th centile. This is a measurement of the maximum depth of liquor in the four quadrants of the uterus (Fig. 30.1).

an amniotic fluid index > 90th centile. This is a measurement of the maximum depth of liquor in the four quadrants of the uterus (Fig. 30.1).

Polyhydramnios occurs in 0.5–2% of all pregnancies and is associated with maternal diabetes (pre-existing or gestational, ~20%) and congenital fetal anomaly such as oesophageal atresia (~5%) (Table 30.1).

Table 30.1

Polyhydramnios

| Cause of polyhydramnios | Pathology |

| Increased production from high urine output | Maternal diabetes, recipient of twin–twin transfusion |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | Oesophageal atresia, duodenal atresia, bowel obstruction or Hirschsprung disease |

| Poor swallowing because of neuromuscular problems or mechanical obstruction | Anencephaly, myotonic dystrophy, facial tumour, macroglossia or micrognathia |

Even in the absence of an identifiable cause, the vast majority), polyhydramnios is associated with an increased rate of:

![]() placental abruption

placental abruption

![]() malpresentation

malpresentation

![]() cord prolapse

cord prolapse

![]() a large-for-gestational-age infant

a large-for-gestational-age infant

![]() requiring a caesarean section

requiring a caesarean section

![]() postpartum haemorrhage

postpartum haemorrhage

![]() premature birth and perinatal death.

premature birth and perinatal death.

When polyhydramnios is confirmed by ultrasound it is important to arrange a growth and anomaly ultrasound scan (if not already performed) and a glucose tolerance test. Red cell antibody screening is undertaken to exclude alloimmune haemolytic disease (p. 315). Only rarely does it become necessary to aspirate liquor for maternal comfort since. If it is aspirated, it quickly re-accumulates. Increased antenatal fetal surveillance is important, as is an increased awareness of the risks of intrapartum complications. Following delivery a paediatrician should examine the baby for congenital anomalies, particularly oesophageal atresia.

Oligohydramnios

Oligohydramnios affects 1–3% of pregnancies and is associated with poorer outcomes than when amniotic fluid volume is normal. Oligohydramnios is unlikely to be specifically suspected by clinical palpation but may contribute to a smaller than expected SFH measurement. Oligohydramnios is diagnosed by ultrasound when the amniotic fluid index is < 5 cm or a single cord free pool of < 2 cm. Oligohydramnios usually presents in the third trimester of pregnancy and is associated with prolonged pregnancy, premature rupture of the membranes, fetal growth restriction and rarely, fetal renal congenital abnormalities (when oligohydramnios may be present from mid-trimester onwards). Oligohydramnios may indirectly cause fetal hypoxia as a consequence of cord compression.

Prolonged pregnancy

This is defined as pregnancy beyond 42 weeks’ gestation. It occurs in up to 10% of pregnancies and is associated with an increase in perinatal mortality due to intrauterine death, intrapartum hypoxia and meconium aspiration syndrome.

Monitoring of post-dates pregnancy

Routinely monitoring pregnancies over 40 weeks with ultrasound or cardiotocography (CTG) appears to confer no demonstrable benefit.

Sweeping the membranes

This involves performing a vaginal examination and inserting a finger through the internal os to separate the membranes from the uterine wall, thus releasing endogenous prostaglandins. It is often uncomfortable for the mother. If a ‘sweep’ is carried out once after 40 weeks’ gestation, it increases the likelihood of spontaneous labour before 42 weeks, avoiding the need for formal induction of labour.

Induction of labour

Induction of labour after 41 weeks reduces the incidence of fetal distress and meconium staining compared with pregnancies managed conservatively; there is also a reduction in the caesarean section rate. It is estimated that 500 inductions of post-dates pregnancies are required to prevent one perinatal death.

Antenatal assessment of fetal well-being

Evidence suggests that there is no clinical need to auscultate the fetal heart rate at each antenatal appointment for low-risk women. However, women often find this reassuring and auscultation should be provided if requested. Maternal perception of fetal movements is important in estimating fetal well-being and women should be encouraged to be aware of their baby’s individual pattern of movements. Any change or reduction in the normal pattern of movements should be investigated, as this can be a sign of fetal compromise or even impending intrauterine death. The value of routine movement counting, such as ‘count to ten’ charts, is not established since a number of studies have failed to demonstrate any benefit.

Fetal cardiotocography (CTG)

The interpretation of CTGs is discussed on page 336. The CTG gives an indication of fetal well-being at a particular time but has limited longer-term predictive value. The routine use of antenatal CTG in low-risk pregnancies is not associated with an improved perinatal outcome and is not recommended.

Fetal biophysical profile (BPP)

Women with pregnancy complications or where pregnancy is prolonged may be offered a biophysical profile, which can be completed in a hospital ‘fetal centre’ or ‘day unit’. In the standard biophysical score, five parameters are assessed, each scored out of 2, and the total out of 10 is used to give an indication of fetal well-being (Table 30.2). Of all the parameters, reduced liquor volume is probably the most predictive of fetal well-being. A major disadvantage of the BPP is that it is potentially time-consuming, requiring up to 30 min of scanning time. As most babies with an abnormal BPP score also have abnormal umbilical artery Doppler flow, it is more appropriate to use Doppler studies. Furthermore, Doppler abnormalities usually precede abnormalities in the BPP.

Table 30.2

Parameters of the biophysical profile

| CTG | More than two accelerations of 15 bpm lasting longer than 15 s in 20 min |

| Fetal breathing | Lasting more than 60 s in 30 min |

| Fetal movements | More than three limb or trunk movements in 30 min |

| Fetal tone | Extremities and neck held in flexion. At least one episode of limb extension and flexion |

| Liquor | Single vertical cord free pool > 2 cm |

Doppler flow velocity studies

Doppler ultrasound examination of the umbilical arteries is used as an assessment of downstream placental vascular resistance. It semi-quantitatively assesses blood flow, and reduced blood flow in fetal diastole correlates with fetal compromise. In severe compromise, diastolic flow may stop altogether or may even reverse. There is no demonstrably beneficial role for routine Doppler studies in low-risk pregnancies.

Doppler examination of the umbilical arteries is useful in pregnancies considered at risk of hypoxia due to impaired placental function, particularly in cases of FGR. In particular, a normal waveform would suggest that a small-for-gestational-age fetus was constitutionally small rather than growth restricted, due to impaired placental function. Abnormal waveforms (absent or reduced end diastolic flow) are associated with an increased risk of structural and chromosomal abnormalities, and detailed sonography is indicated to avoid inappropriate iatrogenic morbidity.

Common antenatal problems

Backache

This occurs as ligaments relax, and a support brace, a firm mattress and flat shoes may be of help. Symptoms of nerve involvement warrant careful clinical examination with referral to physiotherapy in the first instance.

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP)

This is pregnancy-associated pain, instability and dysfunction of the symphysis pubis joint caused by asymmetrical movement of the pelvic bones. It is a common complaint, affecting 14–22% of pregnant women. Referral to obstetric physiotherapists is appropriate and advice provided on positioning and appropriate pain relief. Discussions on mode of delivery should take place, and while planned caesarean section may be considered for extreme cases, vaginal birth is appropriate and recommended for most women.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

The median nerve passes under the flexor retinaculum and receives sensation from the radial half of the hand. Oedema of the carpal tunnel frequently results in compression, leading to paraesthesia of the thumb, index finger and lateral aspect of the middle finger. Holding the wrist hyperflexed for 2 min often reproduces the symptoms. Treatment is by resting with the arm elevated, the use of splints, application of ice, therapeutic ultrasound, a local hydrocortisone injection or, in severe cases, surgical division of the retinaculum.

Constipation

Constipation is a common complaint in pregnancy and can be exacerbated by iron therapy. Usually, dietary advice with recommendation of adequate intake of fibre and fresh fruit and vegetables is all that is required. Laxatives may be used, although bowel stimulants should be avoided due to the potential for collateral stimulation of the uterine smooth muscle.

Haemorrhoids

The weight of the gravid uterus reduces venous return and this predisposes to haemorrhoids. Treatment is by avoiding constipation, and local application of proprietary creams. Rarely, thrombosed and/or prolapsed haemorrhoids require surgical treatment during pregnancy.

Heartburn

Relaxation of smooth muscle by high circulating levels of pregnancy hormones (particularly progesterone) causes relaxation at the gastro-oesophageal junction and reduces lower oesophageal sphincter pressure. This can result in the passage of acidic gastric juice into the lower oesophagus. It is advisable to avoid large meals, spicy meals, fatty foods, alcohol and cigarette smoking. Sleeping in a more upright posture may help. Aluminium- and magnesium-based antacids are widely used during pregnancy, as is the H2 antagonist ranitidine.

Itching

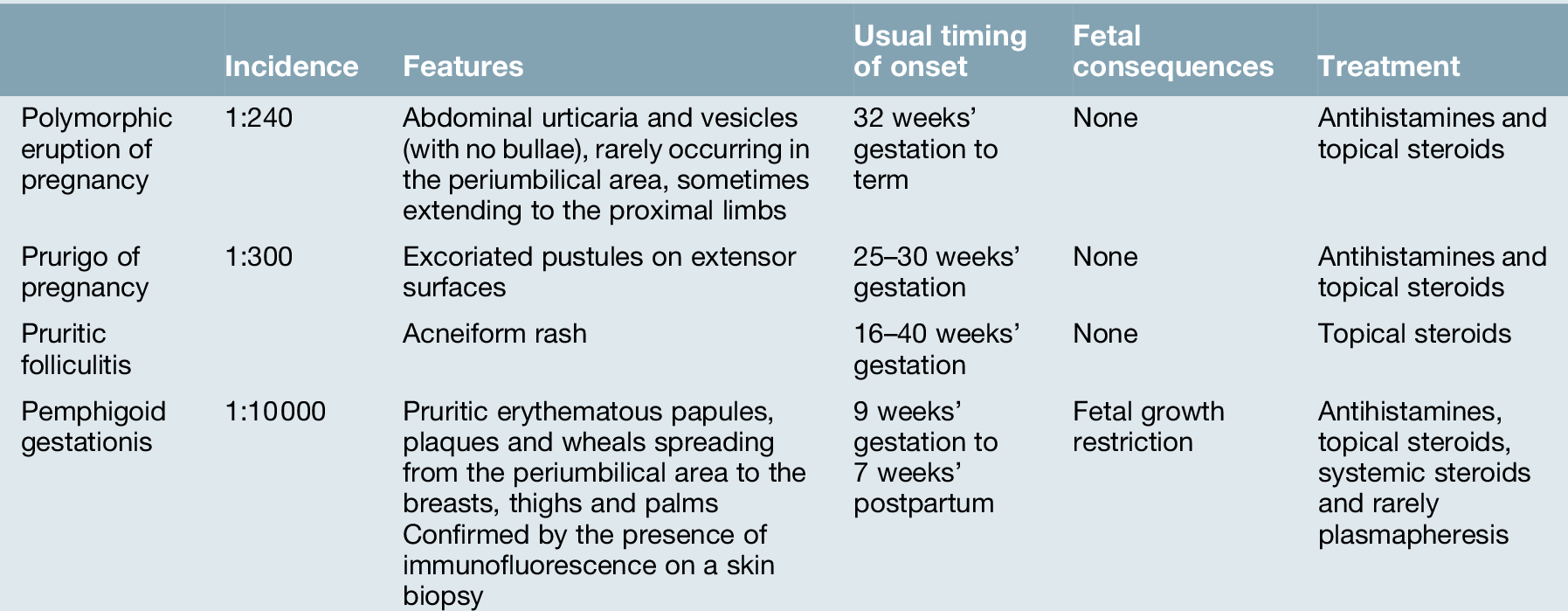

This may be localized or generalized. Vaginal/perineal itching may be due to infection (particularly candidiasis, but less commonly pediculosis pubis or Trichomonas vaginalis). Generalized itching may occur with eczema, urticaria or scabies. If there is a systemic rash, consider one of the four pregnancy-associated dermatoses (see Table 30.3). Itching may also be due to cholestasis of pregnancy, particularly if on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (see p. 259).

Leg cramps

This affects one-third of women in pregnancy. Elevating the end of the bed 20 cm or so may help. Salt supplements are of unproven benefit, although calcium supplements may be of benefit to a minority of women.

Nausea and vomiting

This affects many pregnant women, although some experience no nausea at all. It usually settles at 12–16 weeks but occasionally continues throughout the pregnancy. It is sometimes referred to as ‘morning sickness’ but often persists throughout the day. The sickness often takes the form of retching, rather than true vomiting, and seldom affects the mother’s health. The cause of vomiting is unknown, but the onset and resolution of symptoms may mirror the rise and fall of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) in maternal serum. Furthermore, conditions associated with high level of hCG, for example multiple pregnancies or molar pregnancies, may be associated with more severe symptoms.

Those admitted to hospital due to excessive vomiting are said to have ‘hyperemesis gravidarum’. Inability to retain fluids or solids leads to weight loss, dehydration and electrolyte disturbances, and may very rarely lead to vitamin B deficiency (and polyneuropathy). Liver failure, renal failure and fetal or maternal death are fortunately rare. On admission, the urine should be tested for ketones and renal function quantified by serum urea and electrolytes. Liver function tests may also be deranged in severe hyperemesis, with reduced albumin and increased transaminase levels. It is appropriate to perform an ultrasound scan of the pregnancy if the woman has not previously undergone a scan.

Treatment with intravenous fluids is often sufficient by itself to reduce nausea and represents the initial management. Antiemetics are often used if the vomiting is not settling. No antiemetics are licensed for use in pregnancy, but the risk of teratogenesis is very low, if at all with metoclopramide, cyclizine or prochlorperazine. Only rarely is vitamin B supplementation and/or parenteral feeding required.

Vaginal discharge

Physiological vaginal discharge may be heavier during pregnancy, but infectious causes should be excluded. Candidiasis (thrush) is common and is typically a thick white or creamy coloured discharge with a cottage cheese-like appearance. It may cause vulval itching. When a heavy vaginal discharge is noted, appropriate swabs should be taken to confirm the presence of infection and to suggest appropriate treatment. Positive cultures such as Group B Streptococcus may have consequences for the baby and antibiotics should be offered in labour when the organism has been identified antenatally.

Varicose veins

Varicose veins and ankle oedema are common, as the weight of the gravid uterus impairs venous return. They seldom improve until after delivery. Symptomatic relief in pregnancy may be gained from elevation of the legs at rest and the use of support stockings or tights.

Patient education

This important function is most often undertaken by nominated midwives but may also have input from delivery suite staff, obstetricians and anaesthetists. Many women request guidance and information about normal and abnormal antenatal events and what to expect during the antenatal period, in labour and after delivery. The knowledge gained and the opportunity to discuss her pregnancy with an interested midwife can make a significant difference to the mother’s perception of the pregnancy.

Parentcraft provides education for primigravidae, who have had no previous experience of pregnancy and labour, and advice is given about diet, dental care, smoking cessation and reducing or stopping alcohol intake. Multigravidae may request ‘refresher’ classes. Labour, normal and abnormal, can be explained. Visits to the delivery ward are offered, allowing women to become familiar with the delivery rooms, and provide the first contact with the staff of the delivery suite. Information about analgesia is provided so that women may make an informed decision as to their preference, although they should be encouraged to keep an open mind.

Parentcraft classes targeting a particular group are becoming popular, e.g. multiple pregnancy or teenage classes, where women can meet others in similar circumstances to themselves. In this way, particular difficulties experienced by a group can be discussed and addressed.

Drug misuse

The prevalence of drug and alcohol misuse is increasing, particularly in women of childbearing age. Serious problem misuse and poly-drug misuse are associated with socioeconomic deprivation and an increase in obstetric complications including miscarriage, antepartum haemorrhage, fetal growth restriction, intrauterine death and pre-term labour. Care requires to be directed towards social factors before any substantial impact on obstetric problems can be realistically achieved. Pregnancy may provide a window of opportunity to provide real help, breaking a cycle of poor parenting that might otherwise in turn lead to continuing health problems in the next generation.

The antenatal booking history should cover:

![]() type of drug (Table 30.4):

type of drug (Table 30.4):

![]() street drugs, e.g. heroin, amphetamines, cocaine

street drugs, e.g. heroin, amphetamines, cocaine

![]() pharmacological preparations (usually illicit and/or prescribed), e.g. benzodiazepines, buprenorphine and analgesics, particularly DF118 and other codeine compounds, tramadol

pharmacological preparations (usually illicit and/or prescribed), e.g. benzodiazepines, buprenorphine and analgesics, particularly DF118 and other codeine compounds, tramadol

![]() prescribed preparations, usually methadone

prescribed preparations, usually methadone

Table 30.4

Fetal effects of drugs

| Drug | Effect on fetus |

| Alcohol | Fetal alcohol syndrome is rare (fetal growth restriction, microcephaly, craniofacial abnormalities and mental retardation). However, consumption of even small amounts of alcohol has been associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, which include a reduction in birth weight, intellectual impairment, developmental difficulties, hyperactivity and attention deficit disorder |

| Smoking (tobacco) | There is evidence that babies born to mothers who smoke during pregnancy are at increased risk of low birth weight, premature labour, stillbirth and sudden infant death syndrome |

| Amphetamines | Uncertain magnitude of increased risk of some congenital anomalies. Possible adverse behavioural outcomes in childhood |

| Benzodiazepines | Neonatal withdrawal occurs at levels associated with abuse, even after quite brief use. ‘Floppy infant syndrome’ may occur if high doses have been given to a non-abusing mother in the 15 h prior to delivery |

| Ecstasy | Possible impaired motor development |

| Cannabis (hash, marijuana) | There have been no demonstrable teratogenic effects, but there is probably an increased incidence of fetal growth restriction |

| Opiates/opioids (e.g. heroin, methadone, DF118, buprenorphine) | Methadone and heroin are associated with fetal growth restriction and pre-term labour. Buprenorphine and DF118 probably have similar associations to heroin but with DF118, there is increased severity of neonatal withdrawal symptoms |

| Cocaine and ‘crack’ | There is an increased risk of abruption, premature rupture of membranes, fetal growth restriction and sudden infant death syndrome |

![]() pattern of use, dose, route, frequency, and method of financing supply

pattern of use, dose, route, frequency, and method of financing supply

![]() social support, the other children, partner, family, friends, social work involvement, clothing, food, shelter and transport

social support, the other children, partner, family, friends, social work involvement, clothing, food, shelter and transport

![]() impending legal problems

impending legal problems

![]() risks of infection including HIV, hepatitis B/C counselling with or without testing

risks of infection including HIV, hepatitis B/C counselling with or without testing

![]() domestic abuse – this is a common occurrence within all groups of pregnant women, but more prevalent among women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and those using illicit substances. All women should be asked about domestic violence at the booking visit.

domestic abuse – this is a common occurrence within all groups of pregnant women, but more prevalent among women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and those using illicit substances. All women should be asked about domestic violence at the booking visit.

There may be poor self-esteem following a lack of trusting relationships, lack of positive body image, and concerns about the woman’s abilities to be a parent.

Management

Social factors

Women who take illegal drugs may have a chaotic lifestyle, are often vulnerable and are difficult to reach. As well as risks attributed to their lifestyle, pregnancy outcome is compounded by various additional nutritional and social factors. Attendance for antenatal care may often compete with more immediate problems (e.g. seeing the social worker or lawyer, or getting money/drugs, etc.) but if such care can be delivered locally with flexible access and be combined with confidentiality, non-judgemental consistency, access to social workers and legal aid, then fuller and more effective care can be achieved.

Users of opiates/opioids

For opiate/opioid users it is worth considering transfer to methadone (which is metabolized more slowly, and therefore has more stable levels, and less risk of fetal distress and pre-term labour associated with sudden withdrawals or fluctuations in serum opiate levels). Those stabilized on methadone alone probably have a lower neonatal mortality than those still taking heroin. There may also be improved prenatal attendance.

Detoxification

There are theoretical fetal risks from very rapid opiate/opioid detoxification but in practice, the true fetal risks from even ‘cold turkey’ detoxification are relatively small. Despite this, patients undergoing rapid detoxification should be managed on an obstetric unit, or at least under the close supervision of an obstetrician with an interest and experience in substance misuse. It has been suggested that the risks of detoxification (whether rapid or gradual) may be higher in the first and third trimesters, but practical experience does not bear this out. The goal should be to reduce drug use to a level compatible with stability (e.g. with methadone), not necessarily aiming for complete abstinence.

Neonatal complications

There is an increased incidence of fetal growth restriction, pre-term delivery and sudden infant death syndrome. Neonatal withdrawal (neonatal abstinence syndrome) is particularly associated with opiates/opioids and benzodiazepines, and are worse if they have been used together. Severity is dose-related and timing depends on the rate of drug metabolism, e.g. heroin and morphine are metabolized rapidly and signs usually develop within 1 day, whereas methadone is metabolized more slowly and signs usually occur at between 3 and 5 days. Typically, babies are hungry but feed poorly. There is hyperexcitability (increased reflexes and tremor), gastrointestinal dysfunction (finger sucking, regurgitation, diarrhoea) and respiratory distress. Treatment options include replacement for those who have been exposed to opiates/opioids. The severity of withdrawal symptoms is reduced by breastfeeding.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

Excessive alcohol use in pregnancy is linked with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) being at the most affected end of the spectrum. It is unclear as to how much, if any, alcohol can be safely consumed in pregnancy. FASD varies in presentation, but can include facial dysmorphology, intellectual and developmental delay, attention deficit disorders and hyperactivity to varying degrees of severity. Difficulties in diagnosis mean that management often only commences when the child fails to meet developmental milestones.