41 Anorectal Disorders

• Structures proximal to the dentate line are insensate, but tissue external to this boundary can be painful when damaged by trauma, infection, or inflammation.

• An anoscope should be used to directly visualize the internal anatomy if abnormalities are suspected.

• Internal hemorrhoids cannot be distinguished from normal rectal tissue by digital rectal examination. Anoscopy is required to visualize suspected internal hemorrhoids.

• Thrombosed external hemorrhoids are treated with an elliptical incision rather than a linear incision and drainage.

• Fissures that are not properly treated may become chronic and develop the classic triad consisting of sentinel pile, deep ulcer, and enlarged anal papillae.

• Pain that subsides between bowel movements is classic for anal fissures.

• Any patient with suspected rectal perforation because of a foreign body (insertion or removal) should undergo proctosigmoidoscopy performed by a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon before discharge.

Perspective

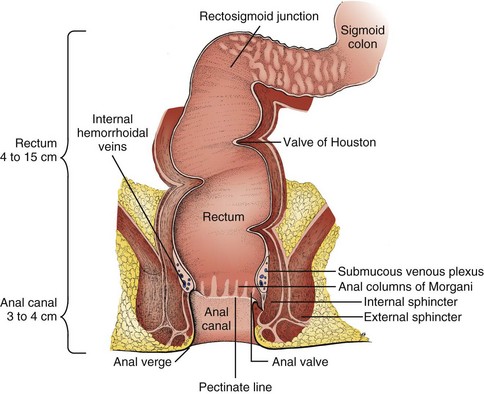

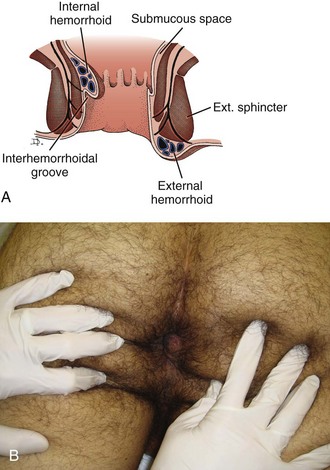

The anorectum marks the end of the digestive tract as it transitions from the endodermal tissues of the colon and intestine to the ectodermal tissues of the skin (Fig. 41.1). The rectum is the portion of the digestive tract that extends distally from the rectosigmoid junction at approximately the level of the S3 sacral vertebral body to the dentate line. At the dentate line, the endodermal tissue transitions to ectodermal tissue. The first 1 to 2 cm is considered the anal canal. This tissue, the anoderm, is squamous in origin but contains no hair follicles or sweat glands. At the anal verge, this tissue transforms to more normal external skin marked by hair follicles, apocrine glands, and subcutaneous tissue.

Examination

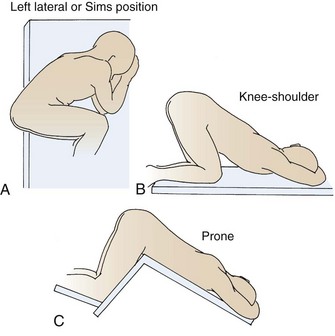

To examine the anorectum, the emergency physician (EP) places the patient in the lateral decubitus position (Sims position) or a knee-to-chest position on the examination table (Fig. 41.2). The anorectal skin, hygiene, and any anatomic abnormalities are inspected. The EP has the patient bear down (Valsalva maneuver) to accentuate any prolapse of the rectum or internal hemorrhoids. The skin of the anorectum is spread to identify fissures that may be hidden in the folds. A 360-degree digital rectal examination is performed, with note being made of the prostate in males and the cervix in females. The sample of stool on the withdrawn glove is assessed for gross or occult blood. If abnormalities are suspected, an anoscope is used to directly visualize the internal anatomy.

Anorectal Abscess

Pathophysiology

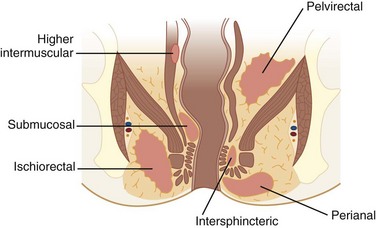

Anorectal abscesses are caused primarily by infection of obstructed anal glands, ducts, and crypts. Abscesses are polymicrobial and involve both anaerobic and aerobic bacteria. Other causes of anorectal abscess are immunosuppression, atypical infection (e.g., tuberculosis, actinomycosis, lymphogranuloma venereum), inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease), trauma (e.g., foreign body), surgery (e.g., anorectal, genitourinary, and gynecologic procedures), malignancy (e.g., rectal carcinoma, leukemia, lymphoma), radiation, and anal fissures. Anorectal abscesses are classified according to location. The four main types are perianal (most common), ischiorectal, intersphincteric, and supralevator (least common) (Fig. 41.3).

Diagnostic Testing and Examination

• Classic history and physical examination findings

• Abdominal examination to evaluate for intraabdominal involvement

• Perianal examination to evaluate for perianal abscess and cellulitis

• Rectal examination to evaluate for deeper abscesses

• Vaginal examination to evaluate for deeper abscesses

• Bedside glucose measurement to evaluate for diabetes mellitus

• Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography to identify deep abscesses when suspected

Treatment

Perianal Abscess

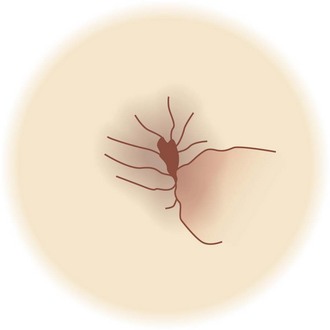

Patients who do not have a complicating disorder and whose perianal abscess (Fig. 41.4) measures 10 cm or smaller may be treated by incision and drainage in the emergency department (ED). Elliptical or cruciate incisions are recommended for better drainage, and procedural sedation may be required. Postincision care consists of sitz baths, stool softeners, and a high-fiber diet.

Cryptitis

Pathophysiology

• Repeated watery stools that can cause trauma or deposits in the crypts

• Direct trauma from large, hard stools

• Inflammation from adjacent structures

• External sources of infection, such as parasites or foreign bodies

If left untreated, cryptitis can lead to perirectal abscess, anal fissure, or anal fistula.

Anal Fissure

Treatment

Medical treatments that are most common and most effective for anal fissures are as follows:

• Warm sitz baths for 15 minutes three times per day

• Oral analgesics (narcotics increase constipation and should thus be avoided)

• Topical anesthetics such as lidocaine jelly

• Topical 0.2% nitroglycerin ointment, which may reduce sphincter spasm but is associated with higher recurrence rates

• Topical calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine, diltiazem), which are also associated with higher recurrence rates

Anal Fistula

Anorectal Foreign Bodies

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Although the majority of patients give an accurate history,1 some have vague complaints of abdominal pain or an unlikely story about how the object became lodged in the rectum. In the ED, every effort must be made to ascertain the type, shape, number, and composition of a retained foreign body, as well as how long it has been in the anorectum, before removing it.

Diagnostic Testing and Examination

The shape, composition, surface, contour, and orientation of a foreign body influence the ultimate method of removal. Most foreign bodies can be classified as low lying and therefore palpable in the rectal ampulla or as high lying, at or proximal to the rectosigmoid junction.2

Examination and diagnostic testing should include the following:

• Thorough palpation of the abdomen (to identify masses, peritonitis)

• Flat and upright radiographs of the abdomen

• Digital rectal examination (if the object is not sharp by patient report and does not appear sharp on radiographs)

Anoscopy to visualize the foreign body should be considered.

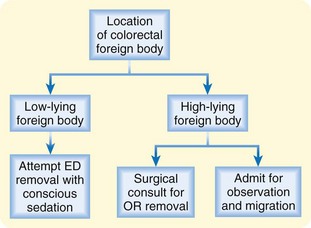

Treatment

Treatment of an anorectal foreign body is based on the results of abdominal and rectal examination, as well as plain radiographs (Fig. 41.5). Patients with palpable, low-lying foreign bodies can undergo conscious sedation and local anesthesia for attempted removal in the ED. Patients with high-lying foreign bodies or risk for perforation should be managed operatively.

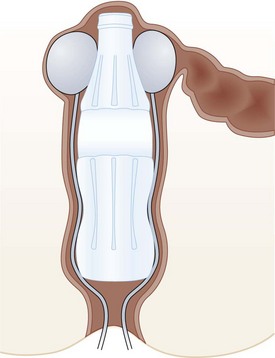

Foley Catheter Removal of Anorectal Foreign Bodies

A Foley catheter can be used to break the suction caused by insertion of an object with a diameter similar to that of the colon or rectum; the procedure is as follows (Fig. 41.6):

1. Place the patient in the lithotomy position.

2. Pass one or more Foley catheters beyond the foreign body.

3. Insufflate air to break the suction.

4. Inflate the Foley balloons.

5. While grasping the foreign body and applying gentle traction with either hands or forceps, slowly remove the catheter or catheters with moderate pressure.

Hemorrhoids

Pathophysiology

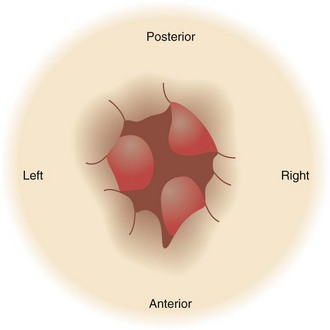

The internal hemorrhoidal veins are located above the dentate line. Their blood supply is derived from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus, and drainage is into the portal system by way of the superior rectal veins and the inferior mesenteric vein. They also communicate with the external hemorrhoidal veins. Internal hemorrhoids are covered by transitional or columnar epithelial mucosa without pain fibers. They are nearly always in the same positions: left lateral (9 o’clock), right posterolateral (5 o’clock), and right anterolateral (2 o’clock) (Fig. 41.7). They are classified into four categories according to severity (Table 41.1).

| SEVERITY (DEGREE) | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| First | No prolapse; painless bleeding |

| Second | Prolapse with straining and spontaneous reduction Mild discomfort and bleeding |

| Third | Prolapse with straining, which requires manual reduction Some throbbing pain, itching, bleeding, and mucus discharge |

| Fourth | Permanent prolapse that cannot be reduced Pain and bleeding common Potential for thrombosis and strangulation |

Treatment

As a rule, most hemorrhoids should be treated conservatively, as follows:

• Warm sitz baths for 15 minutes three times per day

• Stool softeners and bulk laxatives (those causing liquid stool, which could lead to cryptitis, should be avoided)

• 0.2% topical nitroglycerin ointment to treat pain by decreasing sphincter spasm

• Topical anesthetics and steroid creams, though controversial, provide anecdotal pain relief

• Judicious use of narcotics (stool softeners should also be used if narcotics are prescribed)

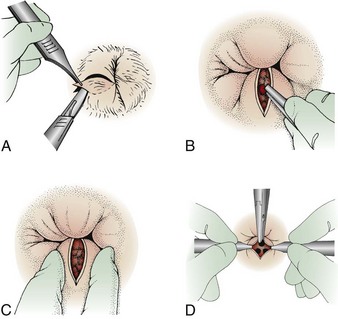

Acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoids can be excised in the ED (Fig. 41.8). Rather than performing simple incision and drainage, the EP should excise the roof of the thrombosed hemorrhoid as an ellipse. Excision of thrombosed hemorrhoids should never be performed in the ED in children or in adults who are immunocompromised or pregnant, in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy, and in patients with portal hypertension.

Excision Procedure

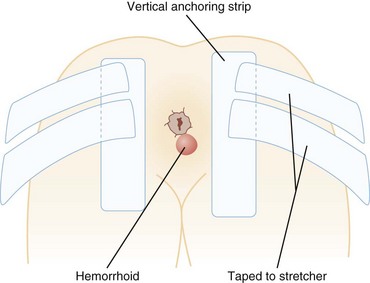

Thrombosed external hemorrhoids can be excised as follows (Fig. 41.9):

1. Put the patient in a prone or left lateral decubitus position.

2. If a single provider is performing the procedure without an assistant, tape the buttocks as shown in Figure 41.10.

3. With a 27-gauge needle, infiltrate bupivacaine with epinephrine into the overlying skin and the skin underneath the clot.

4. Make an elliptical incision in the overlying skin (distal to the anal verge).

5. Excise the clot or clots through this opening.

6. To control bleeding, place a small piece of gauze or absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) into this opening and cover with a pressure dressing.

Fig. 41.9 Schematic of the technique for excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids.

(From Roberts JR, Hedges JR. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.)

The patient should remove the dressing in 6 hours, at the time of the first sitz bath.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Pathophysiology

Perianal hidradenitis suppurativa is a disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that arises from occlusion of the apocrine glands with keratin. It tends to be chronic, recurrent, and primarily localized to areas with the highest density of apocrine sweat glands (groin, axilla, and mammary regions). Sequelae include inflammation, infection, and eventual rupture of the gland with secondary cellulitis of the surrounding tissue. The disease ultimately leads to the formation of chronic draining sinuses.3

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with the early stages of perianal hidradenitis suppurativa typically have a painful boil in the perianal region. Classically, the abscess is deep and round without any central necrosis or fluctuance. The patient may describe similar episodes that resolved spontaneously. Later, more chronic stages of the disease may be manifested as open draining fistulas and sinuses (Box 41.1).

Treatment

Medical treatment of perianal hidradenitis suppurativa consists of weight loss, smoking cessation (if applicable), and the use of antibiotics. Clindamycin, 300 mg twice daily, has been shown to be effective in suppression,3–5 but the disease often returns when use of the antibiotics ceases; topical clindamycin cream is similarly effective. Retinoids may also be tried. Acitretin, 25 mg daily, decreases keratin production and has been shown to reduce the number of outbreaks. Hormonal therapy may also be effective; finasteride was shown to induce remission in a small case study.3

Surgical drainage provides only short-term relief because the condition has a 100% recurrence rate.4,5 Radical excision of the inflamed apocrine tissue carries a recurrence rate of 25%.5

Pilonidal Disease

Pathophysiology

Pilonidal disease is a common disorder that generally affects young adults—those between the ages of 15 and 24 years—with a 3 : 1 male preponderance. Pilonidal disease often causes a considerable amount of suffering, inconvenience, and time away from work. An estimated 40,000 to 70,000 patients are treated annually, mostly as outpatients.6 Approximately 50% of patients with this condition are initially seen by an EP with an acute pilonidal abscess.7

Treatment and Disposition

Treatment is both medical and surgical. ED treatment generally consists of incision and drainage of the abscess. Simple incision plus drainage results in healing in 58% of patients within 10 weeks; of these patients, 40% have no further symptoms and 20% experience only minor symptoms.8 Antibiotics should be prescribed to treat any secondary cellulitis. In one study, metronidazole, 500 mg orally four times per day for 14 days, resulted in more rapid healing than did no antibiotics.8

Proctalgia Fugax

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Proctalgia fugax is usually characterized by sudden episodes of intense pain around the anal ring that can occur at any time and may last from 20 minutes to several hours. Typically, the pain occurs at night and often awakens the patient. The sensation may be associated with an urge to pass stool or flatus. Some patients may experience only one episode in their lifetime. The lifetime prevalence of this condition is 14%.9

Treatment and Disposition

No specific treatment exists for proctalgia fugax. Anecdotal evidence supports the use of warm baths, topical treatment with glyceryl trinitrate, benzodiazepines, topical anesthetics,9 and botulinum toxin.10 Hot packs or direct anal pressure has also been recommended.11

Patients with recurrent disease should be referred to a gastroenterologist.

Proctitis

Pathophysiology

Proctitis is defined as inflammation of the rectal mucosa. It can involve actual loss of mucosal cells, as well as damage to the endothelium of the small arterioles supplying the mucosa. The condition may improve spontaneously, depending on the cause, or may progress with resulting tissue ischemia, mucosal friability, bleeding, ulcers, strictures, and fistula formation. Causes of proctitis are listed in Box 41.2.

Box 41.2 Causes of Proctitis

Autoimmune inflammatory bowel disorders

Sexually transmitted disease–related infections: gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis (usually secondary), herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, lymphogranuloma venereum, amebiasis (oral-anal inoculation)

Non–sexually transmitted disease–related infections: Campylobacter, Entamoeba histolytica, Salmonella, Clostridium difficile

Pruritus Ani

Pruritus ani is a recurrent and unpleasant itching sensation in the anal canal or perianal, perineal, vulvar, scrotal, or buttock areas. Approximately 1% to 5% of the population seeks medical attention for this condition during their lifetime. More men than women experience the disorder, which is more common in the fifth and sixth decades of life.12 Because of the social stigma involved, many patients attempt self-treatment before seeking care. The condition is often poorly understood and improperly treated by health care providers.

Data from Jones DJ. ABC of colorectal disease: pruritus ani. BMJ 1992;305:575-7.

Differential Diagnosis

See Table 41.2.13 Fecal contamination of the perianal skin is the most common cause of pruritus ani.

Treatment

Most cases of pruritus can be treated conservatively with the following measures:

• Gentle cleansing and attention to hygiene of the perianal skin

• Modifications in diet and medications

• Brief courses of topical steroids (long-term steroid therapy should be avoided because it may thin the perianal skin and further exacerbate the condition)

• An oral antipruritic medication such as hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine

• Daily application of topical capsaicin cream (0.006%), which has been shown to be effective in reducing or eliminating symptoms14,15

Rectal Prolapse

Pathophysiology

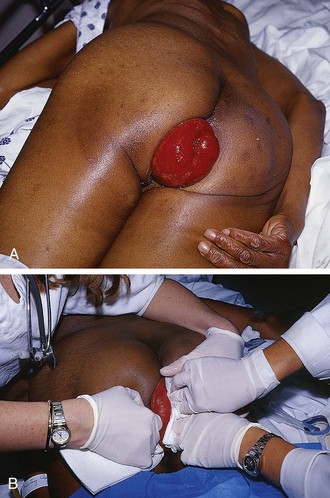

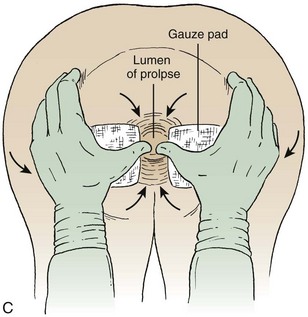

Rectal prolapse or procidentia is a circumferential protrusion of all layers of the rectum through the anus (Fig. 41.11, A). The cause is largely unclear, although the condition seems to be more common in elderly women with a female-to-male preponderance of 6 : 1. Predisposing factors include pelvic floor laxity, pelvic floor neuropathy, persistent straining, chronic constipation, rectal tumors, and disfunction of the anal sphincter.

Treatment and Disposition

Every effort should be made to reduce the prolapsed rectum in the ED to prevent the complications of strangulation, ischemia, ulceration, or perforation. Various methods have been described for reduction, including ice packs, injection of diluted epinephrine, and manual reduction under conscious sedation or general anesthesia (Fig. 41.11, B). Applying ordinary granulated table sugar to the prolapsed tissue, a technique borrowed from veterinary medicine, has been used successfully to quickly reduce the edema and aid in reduction.16

1 Busch BB, Starling JR. Rectal foreign bodies: case reports and a comprehensive review of the world’s literature. Surgery. 1986;100:512–519.

2 Eftaiha M, Hambrick E, Abcarian H. Principles of management of colorectal foreign bodies. Arch Surg. 1977;112:691–695.

3 Slade D, Powell B, Mortimer P. Hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenesis and management. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:451–461.

4 Mortimer P, Lunniss P. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J R Soc Med. 1999;93:420–422.

5 Rubin R, Chinn B. Perianal hidradenitis suppurativa. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1317–1325.

6 Surrell J. Pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1309–1315.

7 Jones DJ. ABC of colorectal diseases. Pilonidal sinus. BMJ. 1992;305:410–412.

8 Allen-Mersh T. Pilonidal sinus: finding the right track for treatment. Br J Surg. 1990;77:123–132.

9 Peleg R, Shvartzman P. Low-dose intravenous lidocaine as a treatment for proctalgia fugax. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:97–99.

10 Katsinelos P, Kalomenopoulou M, Christodoulou K, et al. Treatment of proctalgia fugax with botulinum A toxin. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1371–1373.

11 Vincent C. Anorectal pain and irritation. Prim Care. 1999;26:53–66.

12 Fry RD. Hemorrhoids, fissures, and pruritus ani. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1289–1292.

13 Jones DJ. ABC of colorectal diseases: pruritus ani. BMJ. 1992;305:575–577.

14 Lysy J, Sistiery-Ittah M, Israelit Y, et al. Topical capsaicin—a novel and effective treatment for idiopathic intractable pruritus ani: a randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study. Gut. 2003;52:1323–1326.

15 Anand P. Capsaicin and menthol in the treatment of itch and pain: recently cloned receptors provide the key. Gut. 2003;52:1233–1235.

16 Coburn W, Russell M, Hofstetter W. Sucrose as an aid to manual reduction of incarcerated rectal prolapse. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:347–349.