Chapter 535 Anomalies of the Bladder

Bladder Exstrophy

Clinical Manifestations

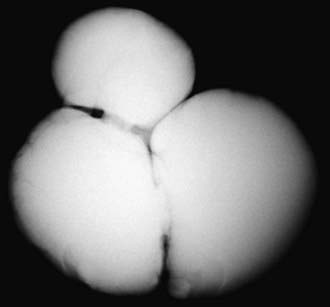

Anomalies of the bladder are hypothesized to result when the mesoderm fails to invade the cephalad extension of the cloacal membrane; the extent of this failure determines the degree of the anomaly. In classic bladder exstrophy (Fig. 535-1), the bladder protrudes from the abdominal wall and its mucosa is exposed. The umbilicus is displaced downward, the pubic rami are widely separated in the midline, and the rectus muscles are separated. In boys, there is complete epispadias with dorsal chordee, and the overall penile length is approximately half that of unaffected boys. The scrotum typically is separated slightly from the penis and is wide and shallow. Undescended testes and inguinal hernias are common. Girls also have epispadias, with separation of the two halves of the clitoris and wide separation of the labia. The anus is displaced anteriorly in both sexes, and there may be rectal prolapse. The pubic rami are widely separated. Persons with exstrophy tend to be shorter than normal.

Long-Term Prognosis

Other Exstrophy Anomalies

Epispadias is in the spectrum of exstrophy anomalies, affecting approximately 1/117,000 boys and 1/480,000 girls. In boys, the diagnosis is obvious because the prepuce is distributed primarily on the ventral aspect of the penile shaft and the urethral meatus is on the dorsum of the penis. Distal epispadias in boys usually is associated with normal urinary control and normal upper urinary tracts and should be repaired by 6-12 mo of age. In girls, the clitoris is bifid and the urethra is split dorsally (Fig. 535-2). In more severely affected boys and in all girls with epispadias, there is total urinary incontinence because the sphincter is incompletely formed, and there is wide separation of the pubic rami. These children require surgical reconstruction of the bladder neck, similar to the final management stage in children with classic bladder exstrophy.

Bladder Diverticula

Bladder diverticula develop as herniations of bladder mucosa between defects of bladder smooth muscle fibers. Primary bladder diverticula usually develop at the ureterovesical junction and may be associated with vesicoureteral reflux, because the diverticulum interferes with the normal flap-valve attachment between the ureter and bladder. In rare circumstances the diverticulum is so large that it interferes with normal micturition by obstructing the bladder neck. Bladder diverticula also commonly are associated with distal urethral obstruction such as posterior urethral valves or neurogenic bladder dysfunction. They occur commonly in children with connective tissue disorders including Williams syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Menkes syndrome (Fig. 535-3). Small diverticula require no treatment other than that of the primary disease, whereas large diverticula can contribute to inefficient voiding, residual urine, urinary stasis, and urinary tract infections and should be excised.

Urachal Anomalies

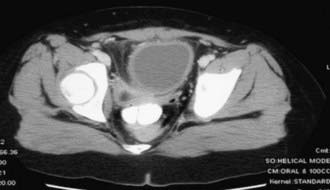

The urachus is an embryologic canal connecting the dome of the fetal bladder with the allantois, a structure that contributes to the formation of the umbilical cord. The lumen of the urachus is normally obliterated during embryonic development, transforming the urachus into a solid cord. Urachal abnormalities are more common in boys than in girls. A patent urachus can occur as an isolated anomaly; it may be associated with prune-belly syndrome or posterior urethral valves (Chapter 534). In this condition there is continuous urinary drainage from the umbilicus. The tract should be excised. Another urachal anomaly is the urachal cyst, which can become infected. Typical symptoms and physical findings include suprapubic pain, fever, irritative voiding symptoms, and an infraumbilical mass, which can be erythematous. Diagnosis is made by ultrasonography or CT (Fig. 535-4). Treatment is intravenous antibiotic therapy and drainage and excision. Other urachal anomalies include the vesicourachal diverticulum, which is a diverticulum of the bladder dome, and umbilical-urachal sinus, which is a blind external sinus that opens at the umbilicus. These lesions should be excised.

Ashley RA, Inman BA, Routh JC. Urachal anomalies: a longitudinal study of urachal remnants in children and adults. J Urol. 2007;178:1615-1618.

Frimberger D, Kropp BP. Bladder anomalies in children. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. ed 9. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:3573-3582.

Galati V, Donovan B, Ramji F, et al. Management of urachal remnants in early childhood. J Urol. 2008;180:1824-1826.

Gambhir L, Höller T, Müller M, et al. Epidemiological survey of 214 families with bladder exstrophy–epispadias complex. J Urol. 2008;179:1539-1543.

Gargollo PC, Borer JG, Diamond DA, et al. Prospective followup in patients after complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2008;180:1665-1670.

Gearhart JP, Mathews R. Exstrophy-epispadias complex. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. ed 9. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:3497-3553.

Jarzebowski AC, McMullin ND, Grover SR, et al. The Kelly technique of bladder exstrophy repair: continence, cosmesis and pelvic organ prolapse outcomes. J Urol. 2009;182:1802-1806.

Mednick L, Gargollo P, Oliva M, et al. Stress and coping of parents of young children diagnosed with bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2009;181:1312-1316.

Schaeffer AJ, Purvers JT, King JA, et al. Complications of primary closure of classic bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2008;180:1671-1674.

Wood HM, Babineau D, Gearhart JP. In vitro fertilization and the cloacal/bladder exstrophy–epispadias complex: a continuing association. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3:305-310.