Chapter 705 Animal and Human Bites

Epidemiology

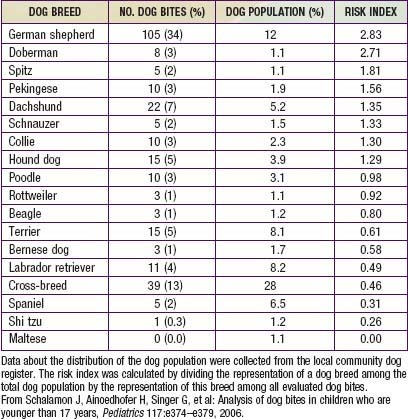

During the past 3 decades, there have been approximately 20 deaths per year in the USA from dog-inflicted injuries; 65% of these occurred in children younger than 11 yr. The breed of dog involved in attacks on children varies; Table 705-1 depicts the risk index by breed from one study of 341 dog bites. Rottweilers, pit bulls, and German shepherds accounted for more than 50% of all fatal bite-related injuries. Unaltered male dogs account for approximately 75% of attacks; nursing dams often inflict injury to humans when children attempt to handle one of their puppies.

Complications

The rate of infection after rodent bite injuries is not known. Most of the oral flora of rats is similar to that of other mammals; however, approximately 50% and 25% of rats harbor strains of Streptobacillus moniliformis and Spirillum minus, respectively, in their oral flora. Each of these agents has the potential to cause infection (Chapter 705.1).

Common causes of soft tissue bacterial infections after dog, cat, or human bites are noted in Table 705-2. High risk for infection after a bite is associated with wounds in the hand, foot, or genitals, penetration of bone or tendons, human or cat bites, delay in treatment longer than 24 hr, presence of foreign material, immunosuppression (asplenia), and crush or deep puncture wounds.

Table 705-2 MICROORGANISMS ASSOCIATED WITH BITES

DOG BITES

CAT BITES

HERBIVORE BITES

SWINE BITES

RODENT BITES—RAT BITE FEVER

PRIMATE BITES

LARGE REPTILE (CROCODILE, ALLIGATOR) BITES

Adapted from Perkins Garth A, Harris NS: Animal bites (website). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/768875-overview. Accessed December 3, 2010. Reprinted with permission from eMedicine.com, 2009.

Treatment (Table 705-3)

Table 705-3 PROPHYLACTIC MANAGEMENT OF HUMAN OR ANIMAL BITE WOUNDS TO PREVENT INFECTION

| CATEGORY OF MANAGEMENT | MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|

| Cleansing | Sponge away visible dirt. Irrigate with a copious volume of sterile saline solution by high-pressure syringe irrigation.* |

| Do not irrigate puncture wounds. Standard precautions should be used. | |

| Wound culture | No for fresh wounds, unless signs of infection exist. |

| Yes for wounds more than 8-12 hr old and wounds that appear infected.† | |

| Radiographs | Indicated for penetrating injuries overlying bones or joints, for suspected fracture, or to assess foreign body inoculation. |

| Debridement | Remove devitalized tissue. |

| Operative debridement and exploration | Yes for one of the following conditions: |

* Use of 18-gauge needle with a large-volume syringe is effective. Antimicrobial or anti-infective solutions offer no advantage and may increase tissue irritation.

† Both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture should be performed.

Modified from American Academy of Pediatrics. Bite wounds. In Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, et al, editors: Red book: 2006 report of the committee on infectious disease, ed 27, EIk Grove Village, IL, 2006, AAP, pp 191–195.

Few studies unequivocally demonstrate the efficacy of antimicrobial agents for prophylaxis of bite injuries. There is general consensus that antibiotics should be administered to all victims of human bites and all but the most trivial of dog, cat, and rat bite injuries, regardless of whether there is evidence of infection. The bacteriology of bite wound infections is primarily a reflection of the oral flora of the biting animal and, to a lesser extent, of the skin flora of the victim (see Table 705-2). Because each of the multitudes of aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species that colonize the oral cavity of the biting animal has the potential to invade local tissue, multiply, and cause tissue destruction, most bite wound infections are polymicrobial. Evidence suggests that as many as five different species may be isolated from infected dog bite wounds.

Although tetanus occurs only rarely after human or animal bite injuries, it is important to obtain a careful immunization history and to provide tetanus toxoid to all patients who are incompletely immunized or those in whom it has been longer than 10 yr since the last immunization. The need for postexposure rabies vaccine in victims of dog and cat bites depends on whether the biting animal is known to have been vaccinated and, most importantly, on local experience with rabid animals in the community (Chapter 266). In developing countries, bites from dogs, cats, foxes, skunks, and raccoons carry a high risk of rabies. Annually worldwide, animal bites result in more than10 million postexposure treatments. An estimated 55,000 deaths due to rabies occur each year, although this number probably represents an underestimation. Most deaths occur in low-income families in developing countries. The local health department should be consulted for advice in all instances in which the vaccination status of the biting animal is unknown and whether there is known endemic rabies in the community. Postexposure prophylaxis for hepatitis B should be considered in the rare instance in which an individual has sustained a human bite from an individual who is at high risk for hepatitis B (Chapter 350).

Prevention

It is possible to reduce the risk of injury with anticipatory guidance. Parents should be routinely counseled during prenatal visits and routine health maintenance examinations about the risks of having potentially biting pets in the household. All patients should be cautioned against harboring exotic animals for pets. Additionally, parents should be made aware of the proclivity of certain breeds of dogs to inflict serious injuries and the protective instincts of nursing dams. All young children should be closely supervised, particularly when in the presence of animals, and from a very early age should be taught to respect animals and to be aware of their potential to inflict injury (Tables 705-4 and 705-5).

| DOG CHARACTERISTICSS | RECOMMENDED HUMAN BEHAVIOR |

|---|---|

| Dogs sniff as a means of communication. | Before petting a dog, let it sniff you. |

| Dogs like to chase moving objects. | Do not run past dogs. |

| Dogs run faster than humans. | Do not try to outrun a dog. |

| Screaming may incite predatory behavior. | Remain calm if a dog approaches. |

| The order of precedence needs to be in evidence. | Do not hug or kiss a dog. |

| Direct eye contact may be interpreted as aggression. | Avoid direct eye contact. |

| Dogs tend to attack extremities, face, and neck. | If attacked, stand still (feet together) and protect neck and face with arms and hands. |

| Lying on the ground provokes attacks. | Stand up. If attacked while lying, keep face down and cover the ears with the hands. Do not move. |

| Fighting dogs bite at anything that is near. | Do not try to stop 2 fighting dogs. |

From Schalamon J, Ainoedhofer H, Singer G, et al: Analysis of dog bites in children who are younger than 17 years, Pediatrics 117:e374–e379, 2006.

Table 705-5 MEASURES FOR PREVENTING DOG BITES

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Dog bite-related fatalities—United States, 1995-1996, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 46:463–467, 1997.

Bibliography

Ertl HCJ: Novel vaccines to human rabies, PLoS Negl Trop Dis 39:e515, 2009.

705.1 Rat Bite Fever

Clinical Course

The incubation period for the streptobacillary form of rat bite fever is variable, ranging from 3-10 days. The illness is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever up to 41°C (fever occurring in >90% of reported cases), severe throbbing headache, intense myalgia, chills, and vomiting. In virtually all instances, the lesion at the cutaneous inoculation site has healed by the time the systemic systems first appear. Shortly after the onset of the fever, a polymorphic rash occurs in up to 75% of patients. In most patients, the rash consists of blotchy, red maculopapular lesions that often have a petechial component; the distribution of the rash is variable, but it usually is most dense on the extremities (Fig. 705-1). Hemorrhagic vesicles may develop on the hands and feet, and are very tender to palpation (Fig. 705-2).

Figure 705-1 Maculopapular rash with small dark red eruptions on hand of person with rat-bite fever.

(From Van Nood E, Peters SH: Rat-bite fever, Neth J Med 63:319–321, 2005.)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of the streptobacillary form of rat bite fever is difficult, because the disease is uncommon and is often confused with Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Chapter 220) or, less commonly, meningococcemia (Chapter 184). Furthermore, S. moniliformis is difficult both to isolate and to identify with classic bacteriologic techniques. The organism is fastidious, requires enriched media for growth, and is inhibited by sodium polyanetholsulfonate, an additive present in most commercial blood culture bottles. A definitive diagnosis is made when the organism is recovered from blood or joint fluid or is identified in human samples with molecular technology such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, which has been used successfully with humans and laboratory animals.

Dong JP, Olano JW, McBride JW, et al. Emerging pathogens: challenges and successes of molecular diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2008;20:185-197.

Elliott SP. Rat bite fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:13-22.

Gaastra W, Boot R, Ho HT, et al. Rat bite fever [review]. Vet Microbiol. 2009;133:211-228.

Ojukwu IC, Christy C. Rat-bite fever in children: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:474-477.

van Nood E, Peters SH. Rat-bite fever. Neth J Med. 2005;63:319-321.

705.2 Monkeypox

Clinical Course

Earl PL, Americo JL, Wyatt LS, et al. Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature. 2004;428:182.

Essbauer S, Pfeffer M, Meyer H. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet Med. 2010;140:229-236.

Ligon BL. Monkeypox: a review of the history and emergence in the Western hemisphere. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15:280.

Maskalyk J. Monkeypox outbreak among pet owners. CMAJ. 2003;169:44.

Parker S, Handley L, Buller RM. Therapeutic and prophylactic drugs to treat orthopoxvirus infections. Future Virol. 2008;3:595-612.

Sejvar JJ, Chowdary Y, Schomogyi M, et al. Human monkeypox infection: a family cluster in the midwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1833.