Aneurysms and other peripheral arterial disorders

Aneurysms (see Table 42.1)

Table 42.1

Clinical presentation and pathophysiology of aortic, iliac, femoral and popliteal aneurysms

| Clinical presentation | Pathophysiology |

| Asymptomatic—discovered incidentally as pulsatile mass in abdomen, groin or popliteal fossa, on abdominal X-ray, CT or ultrasound scan | Progressive aneurysmal dilatation. May be self-limiting if hypertension and smoking controlled |

| Symptomatic—abdominal or back pain with tender aneurysm. Needs urgent surgery | Rapidly expanding aneurysms cause pressure on adjacent structures |

| Sudden death—acute, usually fatal, cardiovascular collapse. Often misdiagnosed as myocardial infarction | Sudden rupture of aneurysm only detected at autopsy or in the dissection room |

| Leaking/ruptured aneurysm—ill-defined back or abdominal pain often simulating ureteric colic or other abdominal emergency. Diagnostic if accompanied by transient collapse. Sometimes a history of recent similar episodes. Pulsatile abdominal mass palpable in 50% | Dilatation and thinning of the wall of an aneurysm leading to leakage of blood into retroperitoneal tissues—usually leads to catastrophic rupture within hours |

| Symptoms and signs of acute severe leg ischaemia; often pulsatile popliteal aneurysm on contralateral side | Sudden thrombotic occlusion of aneurysmal popliteal artery |

| Complete arterial occlusion—sudden distal ischaemia affecting lower limb due to embolism of thrombus from within aneurysm | Thrombotic occlusion of popliteal artery |

| Screening—discovered on population screening or opportunistic screening for aneurysm |

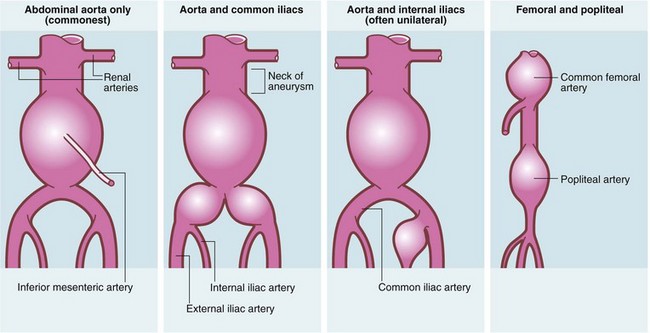

Degenerative aneurysms are usually fusiform, slowly expanding in diameter. As it enlarges, the vessel wall thins, expansion accelerates and the risk of rupture increases. Most abdominal aortic aneurysms involve only the infrarenal aorta; some extend distally to involve common iliac arteries; sometimes there are separate aneurysms of internal iliac arteries (see Fig. 42.1). A few extend proximally to become thoraco-abdominal aneurysms.

Fig. 42.1 Patterns of aneurysm formation

About 25% have more than one aneurysm either in continuity (common iliac, internal iliac, thoraco-abdominal) or not (femoral 10%; popliteal 20%; thoracic 5%). Abdominal aortic aneurysms rarely extend above the renal arteries. External iliacs are never aneurysmal

Clinical presentation of aneurysms (see Table 42.1)

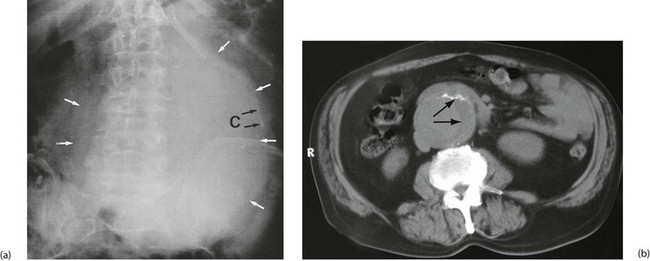

Aorto-iliac aneurysms are often found incidentally. The patient may notice a pulsatile abdominal mass or a pulsatile mass may be discovered on abdominal examination. An aneurysm may also be noticed incidentally on radiological investigation—as calcification on a plain abdominal X-ray, as an obvious aneurysm on CT or, most commonly, on ultrasound scanning for obstructive urinary symptoms (see Fig. 42.2). More recently in the UK, a national AAA screening programme has been approved, with the aim of offering all men an ultrasound scan of the abdominal aorta on reaching 65. Similar schemes are appearing in Denmark, Australia and other countries.

Femoral and popliteal aneurysms are relatively uncommon and usually present as pulsatile masses. The larger they become, the more likely complications are to ensue. Femoral aneurysms occasionally rupture causing pain and massive swelling in the groin. Popliteal aneurysms are liable to undergo thrombosis or embolise, causing an acutely ischaemic leg (see Table 40.2). A thrombosed popliteal aneurysm carries a 50% risk of limb loss. In any patient presenting with an acutely ischaemic leg, it is vital to exclude this diagnosis as successful treatment often requires thrombolysis as well as surgery. Popliteal aneurysms can also rupture and cause a variety of other presentations listed in Table 40.2.

Principles of management of aneurysms

Indications for operation (see Box 42.1)

A leaking or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a surgical emergency. Less than half the patients reach hospital alive, and only about half of those undergoing surgery survive. The majority of patients die of shock before reaching the operating theatre or else of myocardial infarction or acute renal failure after operation. The true mortality of rupture is thus more than 85%. On the other hand, the mortality after elective operation or endovascular repair (EVAR, see p. 513) for aneurysm can be less than 5%. Thus, the decision to operate electively on a known aneurysm depends on the estimated risk of rupture. Indications for operation are summarised in Box 42.1.

Investigation of aneurysms (see Fig. 42.2)

Non-ruptured AAA: For asymptomatic aneurysms considered too small to warrant operation, ultrasonography is used for periodic monitoring, with referral to a surgeon once the size reaches an index diameter (usually 5 or 5.5 cm) or is seen to expand more than 0.5 cm in a year.

Leaking or ruptured AAA: Any patient with a suspected leaking or ruptured AAA should be treated as a true surgical emergency but not necessarily by immediate transfer to the nearest operating theatre. There is good evidence that the survival rate increases when ruptured AAAs are treated by a specialist team of surgeons and anaesthetists, and this may mean transfer to a different centre. Over-aggressive blood pressure resuscitation of the hypotensive patient may convert a stable contained leak into a free rupture, and many clinicians support the use of permissive hypotension to facilitate transfer (see Ch. 15), i.e. not treating relative hypotension whilst the patient remains conscious and free from cardiac symptoms. This principle has increased the time available for transfer and/or further investigation.

Principles of aneurysm surgery

The dilated aneurysmal segment is surgically corrected by means of a graft. Over recent years, there has been a trend towards treating AAAs using minimally invasive stent-graft placement (endovascular repair, EVAR) via the femoral artery. Many patients still, however, undergo traditional open surgery. The indications and relative merits of each technique are shown in Table 42.2. Tube grafts or bifurcation grafts of synthetic material (usually Dacron) are used for aorto-iliac and femoral aneurysms, whilst autogenous saphenous vein is preferred for popliteal aneurysms.

Table 42.2

Comparison of conventional and endovascular therapy for aortic aneurysm

| Conventional surgery | Endovascular therapy | |

| Mortality related to procedure | Approximately 5% | 1.7% |

| Length of hospital stay | 7–10 days | 2–4 days |

| ITU/HDU care needed | Likely | Unlikely |

| Overall cost | £6500 | £8000 |

| Anatomical constraints | Distance between AAA and renal arteries can be less than 15 mm | Needs 15 mm of relatively normal aorta below renals |

| Past medical history | More difficult with previous surgery or peritonitis | Unaffected by previous abdominal surgery |

| Follow-up | Discharge at 3 months. Rescan after 5–7 years. Reintervention unlikely | Frequent CT and ultrasound for life. Reintervention rates high but improving |

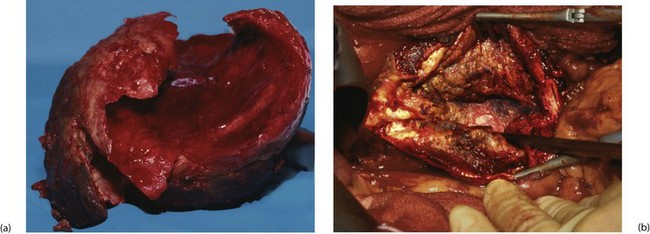

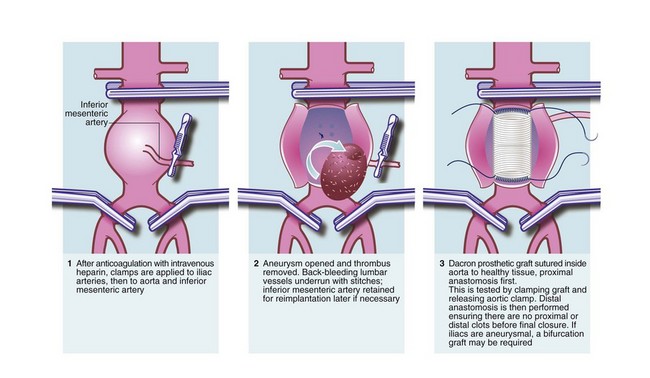

Open abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery (Fig. 42.3):

For abdominal aneurysms, the standard open approach is a long midline or a transverse abdominal incision. The aorta is usually reached via the peritoneal cavity or sometimes via an extraperitoneal approach. The patient is usually anticoagulated perioperatively with intravenous heparin to prevent distal thrombosis, and the iliac arteries and the infrarenal aorta are clamped (see Fig. 42.4). The aneurysm is incised longitudinally and any clot within it removed. Bleeding lumbar arteries opening into the posterior aortic wall are closed with sutures.

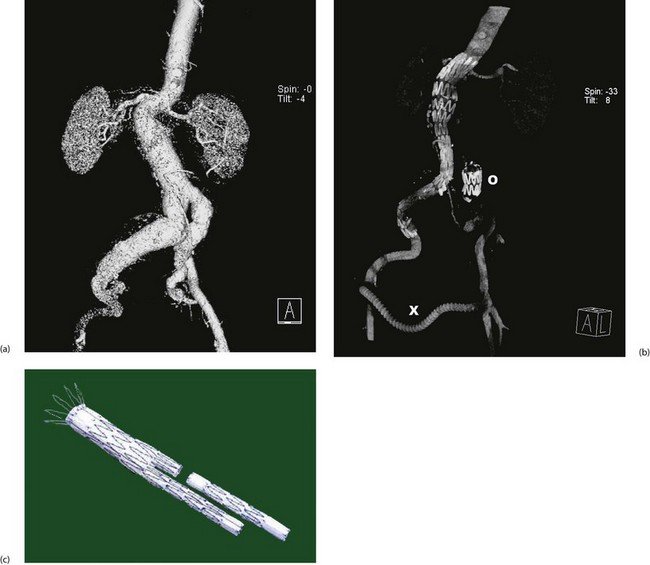

Endovascular aneurysm repair (see Fig. 42.5): Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is a minimally invasive technique employing combined stent-grafts. In the UK, NICE has approved it but recommends that clinicians ensure patients fully understand the long-term uncertainties and potential complications, including endovascular leaks, the possibility of secondary intervention and the need for lifelong follow-up.

Fig. 42.5 Endovascular aneurysm repair

(a) Pre-procedure CT scan showing lumen of aorto-iliac aneurysm, suprarenal aorta and kidneys. On this view, the much larger diameter of the aneurysmal aortic wall is not visible.

(b) Post-procedure CT scan showing the stent-graft in position extending from the right common iliac to just above the renal arteries. In this case, there were technical problems placing a bifurcation graft and so the left common iliac origin was deliberately blocked with an occluding stent O and the left lower limb was revascularised with a crossover femoro-femoral graft X.

(c) Typical two-piece stent graft. Note the body and one limb are in one piece and the other limb is fitted afterwards. Note also the retaining wires at the proximal end

Other applications of EVAR: Open surgical repair of thoracic aneurysms carries a mortality of 10–20% and a high morbidity but many can be repaired by EVAR using just two small groin incisions. Even ruptured aneurysms (abdominal or thoracic) can sometimes be repaired using this technique, often using local anaesthesia. Incomplete traumatic aortic transsections have also been successfully treated with endovascular therapy. Advances continue to be made in EVAR technology so that more complex cases can be managed via this route.

Upper limb problems (see Table 40.5, p. 488)

Upper limb ischaemia

Ischaemia of the upper limb is rare. This is because atherosclerosis is uncommon here and also because there is a rich collateral blood supply via scapular anastomoses that can bypass subclavian occlusive disease. Upper limb ischaemia usually occurs when the subclavian is compressed at the thoracic outlet or when emboli obstruct the brachial or more distal arteries. Occasionally, vasospastic disorders such as severe Raynaud’s disease cause digital ischaemia. Embolic disease here has similar causes, presentation and treatment to embolism affecting the lower limbs (see Ch. 41 p. 502).

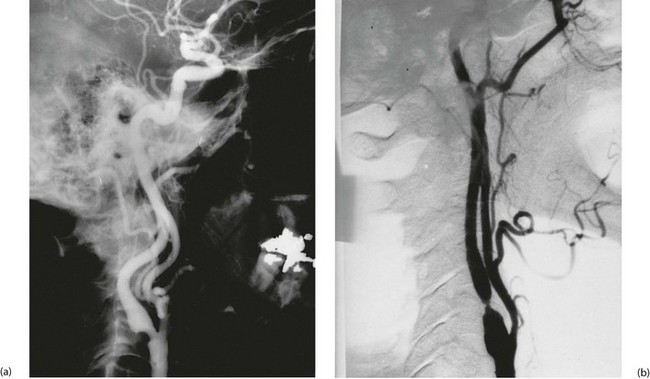

Subclavian steal syndrome

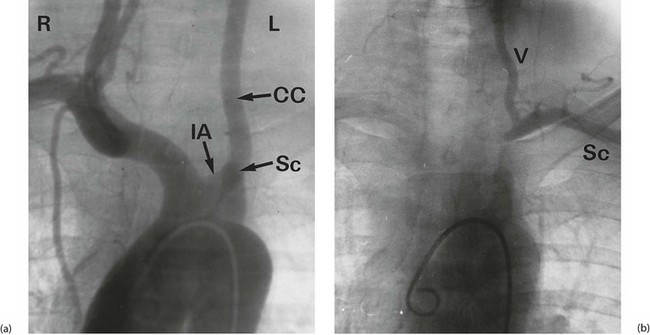

This unusual syndrome is caused by stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian artery proximal to the vertebral artery origin. In consequence, the subclavian is fed by retrograde flow from the vertebral artery via the carotids and circle of Willis. This situation remains tenable and asymptomatic until there is excessive demand by the upper limb, when blood becomes diverted (‘stolen’) from the cerebral circulation causing transient cerebral ischaemia. Figure 42.6 illustrates a classic example. Treatment is by angioplasty or stenting of the subclavian disease or more rarely by bypass with a graft.

Fig. 42.6 Subclavian steal syndrome

Subtraction angiograms from a 55-year-old house-painter who complained of dizziness when painting walls and ceilings. (a) Aortic arch (with ‘pigtail’ arteriogram catheter visible) showing normal right innominate artery with its subclavian and common carotid branches. On the left, the arterial anatomy is anomalous, with the common carotid CC arising from a left innominate artery IA rather than direct from the aorta (a ‘bovine arch’). The left subclavian artery Sc appears to be occluded beyond a short stump. (b) X-ray exposure taken 4 seconds later; the aortic arch and its branches are now clear of contrast, but contrast has appeared in the left vertebral artery V, flowing downwards from the circle of Willis. This has flowed onwards to fill the left subclavian artery Sc retrogradely. Thus there is complete obstruction of a segment of the left subclavian artery proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery, and the vertebral artery now supplies the left upper limb at the expense of the cerebral circulation. This results in episodes of transient cerebral ischaemia at times of high vascular demand from the left upper limb

Extracranial cerebral arterial insufficiency

Pathophysiology of carotid artery disease

Carotid artery disease often results in stenosis, with cerebral blood flow becoming impaired when luminal narrowing exceeds about 70% (Fig. 42.7). Cerebral autoregulation of blood flow is able to compensate up to this point. Rough atherosclerotic plaques without gross narrowing may also be a source of platelet emboli. Small emboli may cause transient ischaemic attacks (including transient blindness, known as amaurosis fugax), with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours. In contrast, large emboli or embolism into critical areas cause major strokes. Asymptomatic stenoses may be discovered on investigation of carotid bruits or as part of general investigation before major arterial surgery elsewhere.

Treatment of carotid artery disease

Medical versus surgical or radiological intervention: The choice of treatment for symptomatic carotid artery stenosis consists of medical anti-platelet therapy (with aspirin 75–150 mg or clopidogrel 75 mg daily), surgical endarterectomy (i.e. removing the obstructing disease and thrombus) or, latterly, minimally invasive stenting. Carotid endarterectomy enjoyed an enormous uncontrolled vogue in the 1970s and 1980s for transient ischaemic attacks, completed stroke and asymptomatic carotid stenosis, particularly in the USA, but the role of surgery became much clearer after major randomised studies from Europe and the USA in 1998. These showed that surgery reduced stroke rate better than medical therapy only in patients with stenosis greater than 70%. In these high-grade stenoses, surgery reduced the annual stroke rate from about 6% in the ‘medical’ group to about 1.5%. However, the trials also showed a substantial risk of stroke or death from surgery of 6–8%.

Acute symptoms: There is good evidence that any symptoms referable to potential carotid disease, even a minor TIA, should be investigated urgently. This is because carotid endarterectomy is most effective at preventing threatened or future strokes if performed within 2 weeks of the herald symptoms. This benefit halves if patients are left untreated for 6 weeks or longer.

Asymptomatic carotid stenosis: The role of surgery in patients with asymptomatic carotid disease remains controversial. Recent trials indicate that even in the hands of surgeons with low complication rates, 15 asymptomatic stenoses need to be treated to prevent a single stroke. The figure for symptomatic disease is about six operations. There is also good evidence that the advent of best medical therapy (anti-platelet treatments, statins, strict blood pressure control and smoking cessation) has further reduced the risk of stroke in asymptomatic carotid disease.

Technique of endarterectomy: Currently, about 2000 carotid endarterectomies are performed annually in the UK. At present, seven males are treated for stenosis for every three females. The usual operation is endarterectomy and may be under general or local anaesthesia (studies have found no differences). The carotid bifurcation is incised longitudinally after clamping the carotid arteries and anticoagulating the patient. A temporary shunt is commonly used to maintain cerebral perfusion, with one end of the shunt in the common carotid below the stenosis and the other in the internal carotid above it, bypassing the operation site. The stenotic plaque is then dissected out and the carotid closed by direct suture (if the artery is large) or patched using vein or synthetic material to maintain the diameter. Carotid surgery carries an appreciable risk of mortality or cerebral complications such as stroke (around 3%) which needs to be taken into account when auditing individual results and when comparing patients treated medically or surgically.

Carotid angioplasty and stenting: Angioplasty with or without stenting is well established for treating peripheral and coronary artery disease but is relatively novel for carotid stenosis. Potential advantages include the lack of a neck incision, lower rates of haematoma formation and cranial nerve damage, and shorter hospital stays, but disadvantages include the risk of embolism during the procedure and possibly a higher rate of late restenosis. Recent meta-analysis suggests stenting causes more strokes in both the short and long term and endarterectomy is associated with cranial nerve injury and a higher cardiac event rate.

Arterial insufficiency in other organs

Blood supply to portions of the bowel may be compromised in four main ways:

• Strangulation. This is a mechanical problem presenting as bowel obstruction described in detail in Chapter 19 p. 271. It may be the result of a hernia (see Ch. 32), volvulus of small or large bowel or fibrous bands resulting from previous surgery (see Ch. 12 p. 172)

• Acute thrombotic or embolic obstruction (Fig. 42.8). This is analogous to acute thrombosis or embolism of the lower limb described in Chapter 41. The cause is usually superior mesenteric artery occlusion and the condition presents as an ‘acute abdomen’ (see Ch. 19)

• Transient ischaemia. This presents as inflammation of the bowel characterised by abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. The condition is known as ischaemic colitis and is discussed at the end of Chapter 29

• Chronic mesenteric artery insufficiency. This rare condition presents with gross weight loss and abdominal pain following eating; it is analogous to intermittent claudication due to lower limb arterial insufficiency

Renal ischaemia

Pathophysiology of renal artery stenosis: This relatively uncommon condition arises in two main ways. In children and young adults, the cause is fibromuscular hyperplasia. In older patients, atherosclerosis is the usual cause. Renal artery stenosis may present with hypertension (ischaemia of kidneys causes poor perfusion, activating the renin–angiotensin system) or functional renal impairment. It is sometimes discovered incidentally on urography as a non-functioning or poorly functioning kidney.

Treatment: Fibromuscular hyperplasia responds well to balloon dilatation, which often results in blood pressure returning to normal. Atherosclerotic disease may be treatable by angioplasty or reconstructive surgery but randomised trials have shown no improvement in blood pressure control or renal function. Renal artery stenosis needs to be recognised in patients having aortic reconstructive surgery, whether for occlusive or aneurysmal disease. This is because hypotension during the operation may initiate thrombotic occlusion of narrowed renal arteries and cause renal failure. These stenoses may need to be treated before operation by angioplasty, or by reconstruction at the time of the aortic operation.

Complications of arterial surgery

Specific complications are summarised in Box 41.2 (p. 501). Local complications include haemorrhage, embolism, thrombosis, graft infection and false aneurysm formation.

Local complications of arterial surgery (Fig. 42.9)

Thrombosis

Sluggish flow leads to thrombosis and may arise for a variety of technical reasons as follows:

• Unrecognised stenosis or occlusion proximal or distal to the reconstruction causing poor inflow or runoff

• Faulty anastomotic technique causing stenosis or partial luminal obstruction

• Dissection of the layers of the distal vessel wall resulting in a loose flap of tunica intima and media which acts as a ‘flap valve’ occluding the lumen

Thrombosis usually occurs in the first few hours after operation and becomes evident by deteriorating colour, temperature and pulses of the affected limb from the satisfactory state achieved at operation. Urgent reoperation is usually required. Judicious use of preoperative anti-platelet agents and/or inhibitors of the coagulation system can help prevent this complication. It is good practice to spend time at the end of the operation ensuring satisfactory flow in the reconstruction and good peripheral perfusion, as well as securing haemostasis. This can avoid the need for reoperation for a thrombosed graft or to arrest haemorrhage in the middle of the night.

Long-term follow-up after arterial surgery

Most patients are followed up long term after surgery or angioplasty to monitor deterioration, to detect new disease and to enable timely intervention if needed. Femoro-popliteal vein grafts can be examined at intervals using duplex Doppler scanning. Such graft surveillance can detect early graft stenoses, enabling them to be treated and the graft preserved, although the efficacy of this is not proven. Aneurysm patients after open operation, on the other hand, can be discharged from regular follow-up 3 months after operation if there are no complications but should be rescanned by ultrasound at 5-yearly intervals for new aneurysms (Fig. 42.10). Stent-graft follow-up needs to be more rigorous as the devices are not as securely fixed as conventional grafts sewn in place. EVAR patients generally undergo CT scanning every 6 months to a year to look for leaks around the graft (endoleaks), but as devices have become more reliable there is a move towards 6-monthly ultrasound scans.