Anesthesia for burn-injured patients

Christopher V. Maani, MD, Peter A. DeSocio, DO and Kenneth C. Harris, MD

Excision and grafting

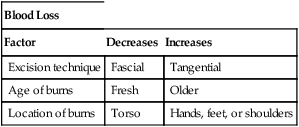

Excision may be either tangential, in which the burn is shaved off until unburned tissue is reached, or fascial, in which all skin and underlying fat is removed down to fascia, usually by using an electrocautery device. Tangential excisions generally produce a better functional and cosmetic result. Fascial excisions may be faster to perform and usually result in less blood loss, as compared with tangential excisions. Whichever method is chosen, these procedures can be quite bloody, with blood loss varying from 123 to 387 mL for each 1% of TBSA of burned tissue excised. Several factors affect the volume of blood loss (Table 233-1).

Table 233-1

Factors Related to Blood Loss in Patients with Burns

| Blood Loss | ||

| Factor | Decreases | Increases |

| Excision technique | Fascial | Tangential |

| Age of burns | Fresh | Older |

| Location of burns | Torso | Hands, feet, or shoulders |