CHRONIC ALCOHOLISM

Approach to the patient

History

Many long case patients may have chronic alcoholism as a significant factor contributing to the overall morbidity. Some important facts to remember in dealing with the problem of alcoholism are as follows:

1. There is a genetic predisposition to alcoholism, so the family history is important.

2. Twenty per cent of alcoholics can stop their habit without help.

3. Mortality in the alcoholic is commonly caused by heart failure (cardiomyopathy), ischaemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, accident or suicide.

In taking a history from patients who abuse alcohol, remember to obtain all relevant details of their habit. Pay particular attention to the amount and type of alcohol consumed each day, the duration of the habit, whether the patient has any drinking partners, how the patient finances their habit, how the family is coping and whether the patient has ever attempted to give up alcohol. Most alcoholics consume 8–10 standard drinks per day; however, this threshold may vary depending on the ethnicity and body habitus of the individual. Most patients may abuse multiple substances. Therefore it is important to ask about other recreational drug use and tobacco smoking. Remember: the patient may withhold the truth due to denial or confabulation. Ask about depression, suicidal ideation, sexual problems, family/marital issues and occupational problems.

The C A G E questionnaire is considered the standardised assessment of the severity of alcohol addiction. Ask the following questions of all suspected alcoholic patients:

Examination

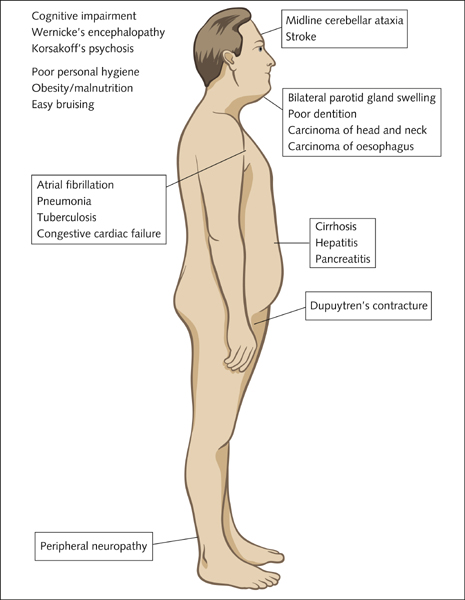

Signs of chronic alcoholism in the physical examination (Fig 11.1) are poor personal hygiene, obesity or malnutrition, multiple ecchymoses due to easy bruising, bilateral parotid gland swelling and Dupuytren’s contracture. Look for atrial fibrillation and evidence of congestive cardiac failure due to alcoholic dilated cardiomyopathy. Perform a detailed neurological examination, looking for midline cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and stroke. Examine the respiratory system, looking for evidence of pneumonia and tuberculosis. Gastrointestinal examination may reveal signs of alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis and pancreatitis. Remember that chronic alcohol consumption is a risk factor for carcinoma of the head and neck and the oesophagus. Perform a cognitive assessment, looking for signs of alcoholic brain damage, Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s psychosis.

Investigations

Do not be surprised to encounter denial of alcoholism, even in the most likely of patients. The following are some investigations that can be done to confirm chronic alcoholism:

Management

1. Acute management of the alcoholic patient includes the administration of oral vitamin B complex (with folic acid) and thiamine 100 mg daily. Alcohol withdrawal (see box) should be managed with diazepam orally, given in decremental doses over 3–5 days as guided by a standard alcohol withdrawal scale.

2. Rehabilitation and abstinence. Some useful steps that can be employed are:

3. Some patients may complain of persistent insomnia. This problem is better managed with behavioural methods, meditation and exercise than with medications.

4. Always offer the patient the option of group support in the form of Alcoholics Anonymous or institutions run by organisations such as the Salvation Army.

5. Discuss with the patient the options of pharmacological anti-craving agents, such as acamprosate and naltrexone. Cognitive behavioural therapy has also shown promise as a means of maintaining abstinence.

Symptoms and signs of alcohol withdrawal

These features start appearing 5–10 hours after the last drink. They usually peak within the first 2–3 days and gradually improve through day 5. Alcoholic seizures occur within the first 48 hours and delirium tremens also occurs during this period. Delirium tremens is characterised by visual, auditory and tactile hallucinations. Some patients experience protracted abstinence syndrome and alcoholic hallucinosis, which can last as long as 6 months.

ALCOHOLIC/CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

Case vignette

A 35-year-old man has been admitted with severe ascites and haematemesis in the background of chronic alcohol abuse and hepatitis C infection. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has revealed bleeding oesophageal varices, which was treated with banding. He has been experiencing increasing daytime somnolence. On examination he has finger clubbing and Dupuytren’s contractures. He demonstrates asterixis and scleral icterus. His abdomen is tender and positive for shifting dullness. He has tense ascites and splenomegaly. His temperature chart demonstrates spiking fevers.

1. What investigations would you request to further work up this man?

2. What is your overall detailed assessment of this man’s clinical status?

3. What immediate management plan would you consider?

4. What is his long-term prognosis?

5. What definitive management options are available to improve this man’s outcome?

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about anorexia, abdominal pain and bloating. Obtain a detailed history on alcohol intake and also enquire into other risk factors for infective hepatitis. Intravenous drug abuse or previous tattoos may suggest hepatitic C infection, and unprotected sexual intercourse with multiple partners may suggest hepatitis B. Ask whether the patient has been tested for or diagnosed with viral hepatitis in the past. Obtain a detailed social history. Ask about the effects of hypogonadism in the male patient (lack of libido and impotence). Check whether the patient has had haemetemesis or melaena, which may be due to erosive gastritis, or oesophageal varicies due to portal hypertension. Perform a cognitive assessment to exclude hepatic encephalopathy.

Examination

1. Look for the sentinel features of chronic alcoholism as described above.

2. The patient may appear drowsy if encephalopathic (disturbed diurnal sleep pattern).

4. Commencing from the periphery, note finger clubbing, leuconychia, Terry’s nails, palmar erythema, palmar crease pallor and Dupuytren’s contractures. Check for asterixis, the flapping tremor of hepatic encephalopathy.

5. There may be proximal muscle wasting.

6. Note any tattoos that may suggest the possibility of associated hepatitic C infection.

7. Look in the eyes for scleral icterus and conjunctival pallor.

8. Do not forget to check for fetor hepaticus.

9. Examine the thoracic region for gynaecomastia and spider naevi.

10. Exclude the presence of a pleural effusion, especially in the right side.

11. Abdominal examination should be very detailed. In the distended abdomen, establish flank dullness and shifting dullness. Note caput medusae. Note the level to which the dullness persists when supine—this level may help decide on the access point for peritoneocentesis and also monitor the progression or regression of ascites. Check for abdominal tenderness. Palpate for hepatomegaly and splenomegaly and try to establish the length to which the organ edges extend below the costal margin. Cirrhotic liver is nodular and firm when palpable. Hard lumps or mass lesions in the liver may suggest the development of hepatoma or hepatocellular carcinoma, which is seen in those with cirrhosis (particularly viral). Auscultate for a Cruveilhier-Baumgarten murmur in the epigastrium, hepatic bruit and note the nature of bowel sounds.

12. In the male patient there may be testicular atrophy.

13. Examine the lower limbs for signs that mirror those of the upper limbs.

14. Check the tendon reflexes for exaggeration due to encephalopathy.

15. Note pitting oedema due to portal hypertension and hypoalbuminaemia.

16. Evidence of right heart failure may suggest the onset of portopulmonary hypertension. Observe the temperature chart or check the temperature for fevers associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (particularly if the patient has abdominal tenderness).

17. Assess the urine output by studying the fluid balance chart. Significant oliguria may be indicative of dehydration or hepatorenal syndrome. The latter is a preterminal event.

Investigations

1. Full blood count—looking for evidence of anaemia (usually macrocytic), leucocytosis and thrombocytopenia (due to sequestration if there is significant splenomegaly). If there has been significant blood loss, the patient may have normocytic or even microcytic anaemia.

2. Coagulation profile—looking for prolonged prothrombin time/INR due to hepatic failure (decreased synthesis of clotting factors)

3. Serum electrolyte profile and renal function indices—looking for evidence of renal failure (hepatorenal syndrome) and hyponatraemia etc

4. Liver function indices including serum billirubin levels and albumin level. In cirrhosis, serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and GGT levels may be normal or abnormal. In alcoholic hepatitis or hepatitis due to other causes, these levels can rise to the thousands. There is a disproportionate elevation of AST relative to ALT in alcoholic liver disease. AST/ALT ratio is over 2 in this case. Patients also have hyperbilirubinaemia and hypoalbuminaemia.

5. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level—high levels are seen with acute hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Progressive elevation of this marker is suggestive of hepatocellular carcinoma.

6. Ascitic fluid analysis for protein levels and microscopy and culture. An elevated (polymorphs) white cell count in the ascitic fluid may be due to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

7. Abdominal ultrasound—looking for evidence of portal hypertension, and also liver consistency and solid mass lesions that may suggest hepatocellular carcinoma, and fluid-filled masses that would suggest cysts. Doppler study helps identify portal vein thrombosis.

8. Measure arterial blood gases, especially if the patient is hypoxaemic on room air. Significant arterial deoxygenation may suggest hepatopulmonary syndrome.

9. Chest X-ray—looking for evidence of pleural effusion, pulmonary congestion (hepatopulmonary syndrome) or enlargement of pulmonary vasculature (portopulmonary hypertension)

10. Echocardiography if there are signs of right heart failure. Elevated pulmonary pressures and right heart strain is very suggestive of portopulmonary hypertension.

11. Measure the urine output—oliguria may suggest hypovolaemia or hepatorenal syndrome.

Other causes of liver disease

It is important to note that hepatitis, cirrhosis, chronic liver disease and hepatic failure can be due to causes other than chronic alcoholism. Where the aetiology is not clear, further diagnostic testing may be necessary. A hepatic disease screen should include the following battery of tests:

• Hepatitis B—HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV, DNA and antibodies to HB surface antigen, e antigen and core antigen

• Hepatitis C—HCV RNA, anti-HCV antibodies

• Hepatitis A—antibodies (IgM) to HAV

• Infectious mononucleosis—Paul-Bunnell test, Monospot test

• Autoimmune hepatitis—antinuclear antibody and antismooth muscle antibody (type 1), anti-LKM1 antibody (type 2), anti-SLP/LP (type 3)

• Hereditary haemachromatosis—serum iron indices, serum ferritin, transferring saturation

• Wilson’s disease—serum copper, caeruloplasmin

• Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency—serum alpha1-antitrypsin levels

• Liver ultrasound—looking for fatty infiltration, cirrhosis, nodularity and to examine portal veins (portal vein thrombosis), hepatic veins (hepatic vein thrombosis) and the biliary tract

• CT scan and/or MRI of liver

• Liver biopsy

Management

1. Alcoholism should be managed as per the discussion previously. Upon addressing and stabilising the withdrawal symptoms, the patient should be given supportive therapy and adequate nourishment. Another main objective of this strategy is to address complications and direct therapy at liver disease based on the stage viz. cirrhosis, hepatitis or fulminant hepatic failure. Associated other pathologies such as viral hepatitis may further influence the management approach.

2. Supportive measures include adequate IV hydration and nutrition. Vitamin supplementation (especially thiamine, pyridoxine and folic acid) is very important. Vitamin K injection may help address the coagulopathy.

3. Significant ascites should be tapped if necessary, with concurrent IV albumin infusion. Measures to treat portal hypertension and diuretic therapy with spironolactone help improve ascites.

4. Patients with hepatitis benefit from oral prednisolone therapy over periods of 4 or more weeks.

5. Abstinence from alcohol is a key objective and all measures to facilitate this should be put in place. Psychological support and counselling together with family or partner support should be provided. Detoxification under professional supervision should be organised.

7. Management of portal hypertension—all patients with cirrhosis are at risk of portal hypertension. The dreaded complication of portal hypertension is bleeding oesophageal and/or gastric varices. Patients with portal hypertension should be treated with a non-selective beta-blocker such as propranolol. Patients with bleeding varices need upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy for variceal banding or sclerotherapy. Patients may require repeat procedures in the event of rebleeding, which is not too uncommon. Measures to ease portal hypertension include transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and creation of a surgical portacaval shunt. Decompression by creating a portosystemic shunt has been observed to worsen hepatic encephalopathy. However, it is very effective at preventing and decreasing rebleeding.

8. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma—there is no consensus on the best approach to the management of this complication of cirrhosis. Some physicians promote watchful waiting if the tumour is not causing any complications. The behaviour of the tumour is highly variable and therefore so is the prognosis. However, as a general rule, life expectancy can vary from 6 months to 2 years from diagnosis. Large tumours can be treated with surgical resection and transplantation. Some centres offer cryoablation of the tumour. Hepatocellular carcinoma can also be managed with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, arterial chemoembolisation or alcohol ablation.

9. Management of hepatic encephalopathy—hepatic encephalopathy is believed to be due to increased blood ammonia levels generated in the intestines that cross the blood–brain barrier. Therefore the management strategy should first address the precipitating factors. Gastrointestinal bleeding and high protein intake have been associated with encephalopathy and therefore control of intestinal bleeding, gastric lavage and decreasing protein intake are important therapeutic steps. Other precipitants include constipation, sepsis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sedative hypnotics such as benzodiazepines too can precipitate encephalopathy and should be withdrawn or withheld safely. Oral lactulose, lactitol or antibiotics such as oral neomycin also improve encephalopathy.

Child-Pugh classification of liver disease

Classification is based on:

Child-Pugh score has three prognostic classes:

Child-Pugh class correlates with patient mortality.

10. Patients with hepatitis C benefit from combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. Acute exposure is treated with interferon monotherapy. Careful patient selection and close monitoring are important in instituting this therapy.

11. Patients with hepatitis B infection benefit from therapy with interferon and lamivudine.

HAEMOCHROMATOSIS

This is the most common autosomal recessive condition in the Caucasian population (affected frequency 1:400 and carrier frequency 1:10). Therefore, the chances of getting a patient with haemochromatosis in the examination are very high. Manifestations may vary from asymptomatic disease or diabetes mellitus to hepatocellular carcinoma associated with cirrhosis. This disease is associated with a mutation in the HFE gene in the short arm of chromosome 6. About 85% of cases manifest Cys 282 Tyr mutation, with 25% manifesting a second mutation, His 63 Asp.

Approach to the patient

History

Ask about:

The patient and the family may have been offered gene testing for the common mutations. Ask about the therapy received and ongoing monitoring of the disease. It is important to assess how the condition has affected the patient’s personal, social, occupational and family life and to gauge the patient’s insight into and knowledge of the condition.

Examination

Look for bronze pigmentation of the skin, which is more pronounced in the face, neck, extensor surfaces, genitals and scars, and for peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease such as leuconychia, palmar erythema, jaundice, spider naevi, evidence of portal hypertension and hepatosplenomegaly. Check for gynaecomastia and lack of android hair distribution. Look for evidence of arthropathy, particularly in the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints and in the knees. Look for signs of congestive cardiac failure. Perform a detailed abdominal examination, looking for features of hepatic malignancy such as firm/hard hepatomegaly or mass lesion in the right upper quadrant. Check for lymphadenopathy and bony tenderness.

Investigations

1. Serum iron, transferrin saturation (> 50% is pathological), and serum ferritin concentration (> 500 mg/mL is pathological)

2. Liver biopsy and the hepatic iron index (normal index is < 1; in haemochromatosis it may be > 2). Liver biopsy may also show micro- or macronodular cirrhosis. Biopsy is also important to exclude hepatocellular carcinoma in the cirrhotic patient.

3. If no liver biopsy has been performed, ask for abdominal MRI to look for the classic appearance of the iron-laden liver.

4. Genetic testing for Cys 282 Tyr mutation should be considered where necessary, if facilities are available.

5. All family members of the index patient should be screened for haemochromatosis by performing serum ferritin levels and transferrin saturations.

Management

1. Weekly or twice-weekly phlebotomy should be performed until the serum ferritin level and transferrin saturation becomes normal. From then onwards, phlebotomy can be performed at 3-monthly intervals or as necessary.

2. Male patients should be supplemented with testosterone to preserve libido and male sexual characteristics.

3. If the patient is anaemic for some reason, they cannot be treated with phlebotomy, and in this situation the treatment option is to use a chelating agent such as desferrioxamine. It should be remembered that phlebotomy has very little effect on joint pathology.