Anatomy of the Respiratory System

I Boundaries and Functions of the Upper Airway

A Boundaries: From the anterior nares to the true vocal cords.

1. Heating or cooling inspired gases to body temperature (37° C).

3. Humidifying inspired gases to a relative humidity of approximately 100% at body temperature.

4. Olfaction: Act of smelling.

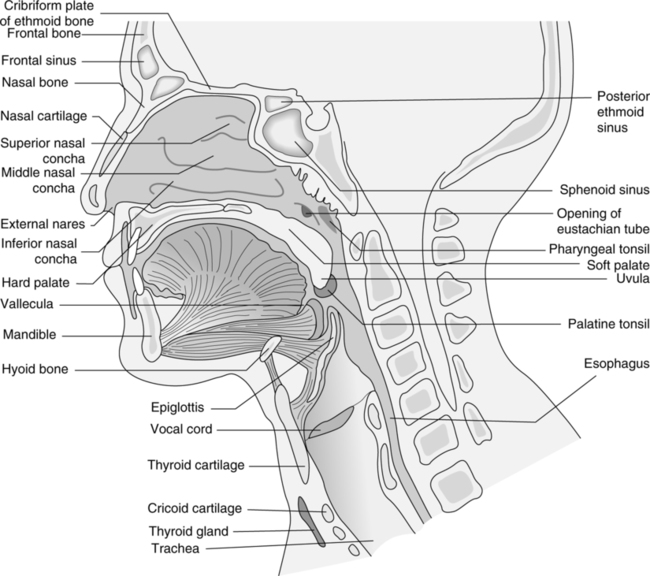

1. The nose is a rigid structure of cartilage and bone; the superior one third is made up of the nasal and maxilla bones, and the inferior two thirds is made up of five large pieces of cartilage (Figure 4-1).

2. The two external openings are called the nostrils, external nares, or anterior nares. Their lateral borders are termed the alae.

3. The nasal cavity is divided into two nasal fossae by the septal cartilage.

4. Each nasal fossa is divided into three regions: vestibular, olfactory, and respiratory.

a. Vestibular region: An area of slight dilation inside the nostril, bordered laterally by the alae and medially by the nasal septal cartilage.

(1) The vestibular region is lined with stratified squamous epithelium (Table 4-1). Layers of relatively flat cells continuously are being produced, replacing those lost at the surface.

TABLE 4-1

Anatomical Comparison of Epithelium in Upper Respiratory Tract

| Structure | Epithelium |

| Vestibular region/nose | Stratified squamous |

| Olfactory region/nose | Pseudostratified columnar |

| Respiratory region/nose | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar |

| Paranasal sinuses | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar |

| Nasopharynx | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar |

| Oropharynx | Stratified squamous |

| Laryngopharynx | Stratified squamous |

| Larynx/above true cords | Stratified squamous |

(2) Coarse nasal hairs (vibrissae) project anteriorly and inferiorly.

(3) Sebaceous glands secrete sebum, a greasy substance that keeps the nasal hairs soft and pliable.

(4) The nasal hairs are the first line of defense for the upper airway, acting as very gross filters of inspired air.

b. Olfactory region: An area in each nasal cavity defined by the superior concha laterally, nasal septal cartilage medially, and roof of the nasal cavity superiorly.

(1) Contained is the olfactory epithelium responsible for the sense of smell.

(2) The olfactory epithelium is yellowish brown and appears as pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells. These cells are interspersed with more deeply placed olfactory cells, whose sensory filament, the olfactory hairs, protrudes to the epithelial surface. Similar in structure to the ciliated cells lining the respiratory region but without the cilia (Figure 4-2).

(3) Largely because of the architecture of the nasal cavity, sniffing causes inspired gases to be drawn to the olfactory region and not much farther into the respiratory tract. This provides a protective mechanism for sampling potentially noxious environmental gases.

c. Respiratory region: An area in each nasal cavity inferior to the olfactory region and posterior to the vestibular region. The respiratory region comprises most of the surface area of the nasal fossa.

(1) Contained in the respiratory region of each nasal fossa are three bony plates called turbinates or conchae. The turbinates extend in a medial and inferior direction from the lateral walls of the nasal fossa.

(2) The three turbinates or conchae (superior, middle, and inferior) overhang and define the three corresponding passageways through each nasal cavity, respectively, the superior, middle, and inferior meati (see Figure 4-1).

(3) Because of the arrangement of the turbinates and folded mucous membrane covering the turbinates in the nose, the respiratory region has a volume of approximately 20 ml and a remarkably large surface area of approximately 160 cm2.

(4) Turbulent flow is created through this region.

(5) Heating, humidifying, and filtering of inspired gases are accomplished by the turbulent flow through this region of the nose. The turbulent flow produces a greater probability that each gas molecule will come in contact with the large surface area of the vascular nasal mucous membrane. This large gas-to-nasal surface interface allows the following:

(a) The abundant underlying vasculature to heat inspired gases to body temperature.

(b) The moist nasal mucous membrane to give up 650 to 1000 ml of H2O per day in bringing inspired gases to a relative humidity of 80% on leaving the nose and entering the nasopharynx.

(c) Particles suspended in the inspired gas to contact the sticky mucous membrane, thus filtering out particles ≥5 μm by inertial impaction to an efficiency of approximately 100%.

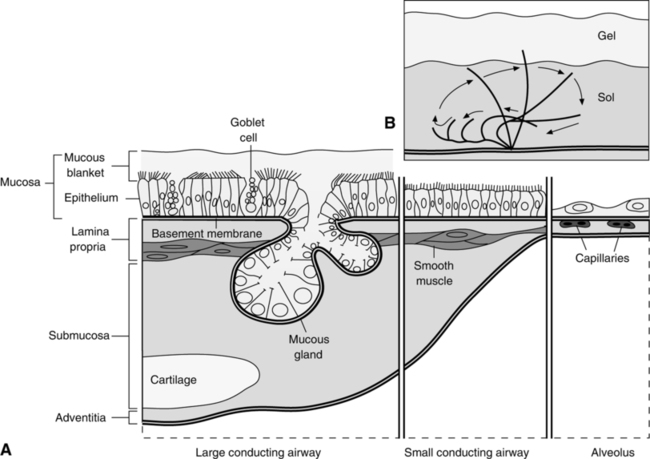

(6) The epithelial lining of the respiratory region of the nasal cavity is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (see Figure 4-2).

(a) The cells are cylindrical and appear to be two cell layers thick because of the high lateral pressures compressing the cells. Actually, the epithelium is only one cell layer thick, with each columnar cell making contact with the basement membrane.

(b) Each columnar cell has 200 to 250 cilia on its surface. Each of the cilia contains two central and nine paired peripheral fibrils. It is the sliding interaction of these fibrils that is thought to cause the beating of the cilia.

(c) Goblet cells and submucosal glands are interspersed throughout the epithelium and, along with capillary seepage, are responsible for production of mucus (100 ml/day in health).

(d) Mucus exists in two layers:

(e) On the forward stroke, the cilia become rigid. Their tips touch the undersurface of the gel layer and propel it toward the oropharynx. On the backward stroke, the cilia become flaccid, fold on themselves, and slide entirely through the sol layer to their resting position without producing a retrograde motion of the gel layer.

(f) The cilia of a particular cell and adjacent cells beat in a coordinated and sequential fashion that produces a motion similar to a wave. This allows a unidirectional flow of mucus. The cilia beat approximately 1000 to 1500 times/min and move the mucous layer at a rate of 2 cm/min.

(g) Functions of the mucus and pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (mucociliary blanket) are:

5. The nose is responsible for one half to two thirds of the total airway resistance during nasal breathing. Therefore, it is not surprising that mouth breathing predominates during stress (e.g., exercise or disease).

6. The nose ends with the outlet of the nasal cavity into the nasopharynx through the internal nares (posterior nares or choanae).

D The oral cavity (see Figure 4-1)

1. The oral cavity extends from the lips to the palatine folds, a double web on each side of the oral cavity where the palatine tonsils reside.

2. The oral cavity is separated from the nasal cavity by the palate. The anterior two thirds is the bony hard palate, and the posterior one third, without bone, is the soft palate.

3. The oral cavity is considered an accessory respiratory passage because air usually only flows through it during stress and exercise.

4. The tongue attached to the floor of the cavity is involved in the mechanical aspects of swallowing, taste, and phonation.

a. The posterior surface is supplied by a nerve ending producing the vagal gag reflex.

b. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.

5. The mucosal surface provides modest humidification and warming of inspired air.

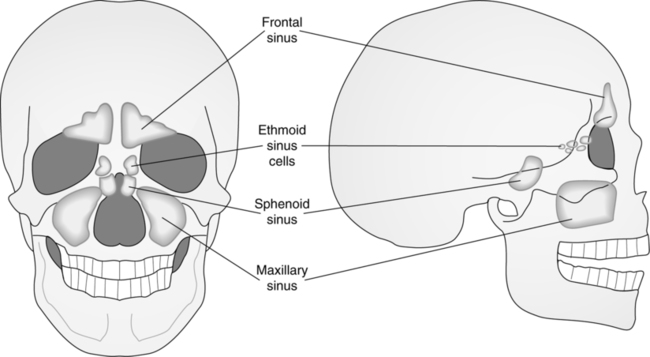

E Paranasal sinuses (see Figures 4-1 and 4-3)

1. Sinuses are cavities of air in the bones of the cranium.

2. The function of the sinuses is not clearly understood, but it may be twofold:

a. To give the voice resonance (prolongation and intensification of sound).

b. To lighten the head to some extent because the space occupied by the sinuses is filled with air rather than bone.

3. The sinuses are absent or rudimentary at birth and grow almost simultaneously with the development of the permanent teeth. Formation of the sinuses is responsible for the alteration in facial shape that occurs at this time.

4. All of the air sinuses are lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and produce mucus, which drains into the nasal meati.

5. If nasogastric tubes or nasotracheal intubation blocks sinus drainage, sinusitis and sinus infection often result.

6. Groups of paranasal sinuses: Frontal, maxillary, sphenoidal, and ethmoidal.

a. The frontal sinuses appear as paired sinuses medial to the orbits of the eye and superior to the roof of the nasal cavity between the external and internal surfaces of the frontal bone. They drain into the anterior portion of the middle meati (middle passageway [cavity] formed by the turbinates).

b. The maxillary sinuses appear as paired sinuses lateral to each nasal cavity and inferior to the orbits of the eye in the body of the maxilla. These sinuses, the largest of all the air sinuses, drain into the middle meati.

c. The sphenoidal sinuses appear as paired sinuses posterior and inferior to the roof of the nasal cavity and superior to the internal nares (choanae) in the body of the sphenoid bone. They drain into the superior meati.

d. The ethmoidal sinuses are paired sinuses that exist in three groups: anterior, medial, and posterior ethmoidal. They exist just lateral to the superior and middle conchae, medial to the orbits of the eyes, inferior to the frontal sinuses, and superior to the maxillary sinuses in the ethmoid bone. The ethmoidal sinuses drain into the superior and middle meati.

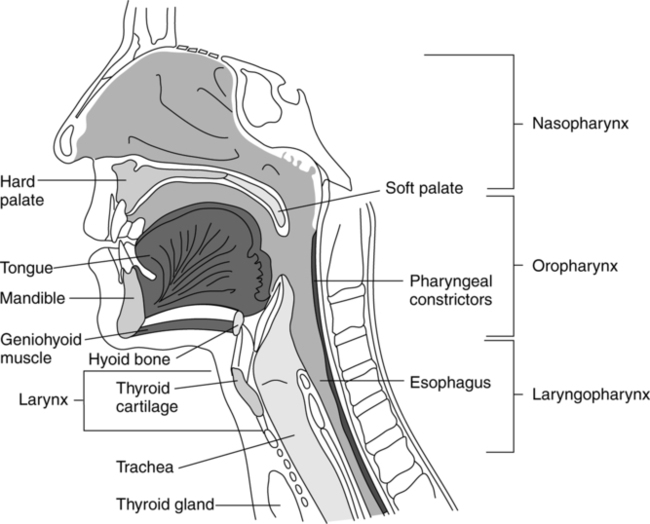

1. The pharynx is a hollow muscular structure lined with epithelium (Figure 4-4).

a. To produce the vowel sounds (phonation) by changing its shape.

b. To serve as a common passageway for ventilatory gases, food, and liquid.

3. The pharynx is approximately 5 in. long and extends from the internal nares (choanae) inferiorly to the esophagus.

4. Sections of the pharynx: Nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx.

a. The nasopharynx is located behind the nasal cavity and extends from the internal nares superiorly to the tip of the uvula inferiorly.

(1) The epithelium is continuous with the epithelium of the nasal cavity and is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium.

(2) The eustachian or auditory tubes open into the nasopharynx on each of its lateral walls and communicate with the tympanic cavity or middle ear (see Figure 4-1).

(a) This allows equilibration of pressure on each side of the tympanic membrane (eardrum) with environmental pressure changes.

(b) Nasal intubation may block the eustachian tube openings and may cause otitis media (middle ear infection) or sinus infections.

(3) The pharyngeal tonsil or adenoid is located in the superior and posterior wall of the nasopharynx.

(a) The pharyngeal tonsil consists of a large concentration of lymphoid tissue comprising the superior portion of Waldeyer’s ring. This ring of lymphoid tissue surrounds and guards the entrance to the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

(4) During the process of swallowing, the uvula and soft palate move in a posterior and superior direction to protect the nasopharynx and nasal cavity from the entrance of food, liquid, or both.

b. The oropharynx is located behind the oral or buccal cavity and extends from the tip of the uvula superiorly to the tip of the epiglottis inferiorly.

(1) The epithelial lining is stratified squamous epithelium.

(2) The palatine tonsils are located lateral to the uvula on the lateral and anterior aspects of the oropharynx.

(3) The lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue, superior and anterior to the vallecula (the space between the epiglottis and base of the tongue).

(4) The two palatine tonsils, one lingual and one pharyngeal (adenoid), are the major components of Waldeyer’s ring.

c. The laryngopharynx or hypopharynx extends superiorly from the tip of the epiglottis to a point inferiorly where it bifurcates into the larynx and esophagus.

(1) The epithelial lining is stratified squamous epithelium.

(2) Major functions of the laryngopharynx:

(3) The laryngopharynx leads anteriorly into the larynx and posteriorly into the esophagus.

(4) The larynx is considered the connection between the upper and lower airways, the exact division being the true vocal cords.

(5) The larynx is considered part of the upper and lower respiratory tract. A complete description is given below.

II Boundaries and Functions of the Lower Airway

A Boundaries: From the true vocal cords to the terminal air spaces (alveoli).

1. Ventilation: To and fro movement of gas (gas conduction).

2. External respiration: Actual gas exchange between body (pulmonary capillary blood) and external environment (alveolar gas).

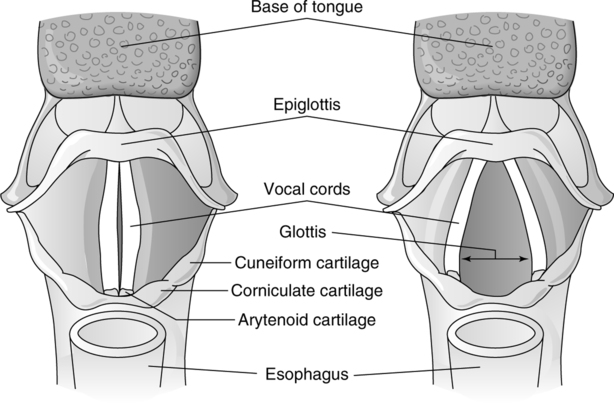

C The larynx (Figures 4-5 and 4-5)

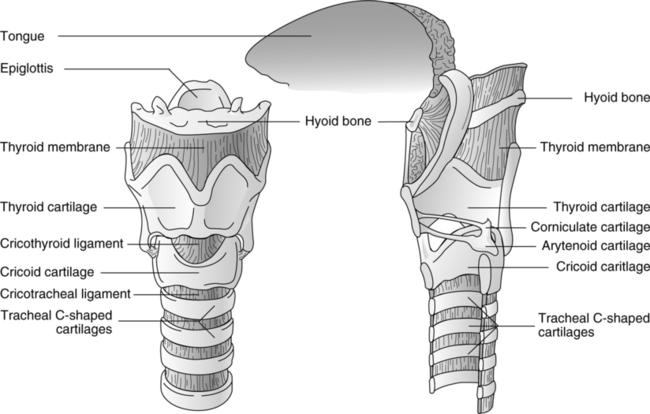

1. The larynx is a boxlike structure made of cartilage connected by extrinsic and intrinsic muscles and ligaments. It is lined internally by a mucous membrane.

3. The larynx extends from the third to sixth cervical vertebrae in the anterior portion of the neck.

4. Unpaired cartilages of the larynx: Epiglottis, thyroid, and cricoid (see Figure 4-5).

(1) Leaf-shaped piece of fibrocartilage.

(2) Anteriorly attached to thyroid cartilage just inferior to the thyroid notch.

(3) Laterally attached to folds of mucous membrane called aryepiglottic folds.

(4) On swallowing, the epiglottis is squeezed between the base of the tongue and thyroid cartilage, causing the epiglottis to pivot in a posterior and inferior direction to cover the laryngeal inlet.

(1) The largest laryngeal cartilage.

(2) The anterior aspect is called the laryngeal prominence or Adam’s apple.

(3) Directly superior to the laryngeal prominence is the thyroid notch.

(4) The posterior and lateral aspects of this cartilage have two superior and two inferior projections: the superior and inferior cornua.

(1) Shaped like a signet ring, the smallest opening in the neonatal airway.

(2) Forms the entire inferior aspect and most of the posterior aspect of the larynx.

(3) There are articulating surfaces for the inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage on the posterolateral surface.

(4) There are articulating surfaces for the paired arytenoid cartilages on the posterosuperior surface.

(5) Lies inferior to the thyroid and superior to the trachea, to which it attaches.

(6) Lies anterior to the esophagus; therefore, external cricoid pressure may facilitate viewing of the glottis during tracheal intubation and may prevent reflux from the stomach by compressing the esophagus.

5. Paired cartilages of the larynx: Arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform (see Figure 4-6).

(1) Shaped like upright pyramids.

(2) The base of each cartilage articulates with the posterosuperior surface of the cricoid cartilage.

(3) Each arytenoid cartilage has a ventral-medial projection from its base called the vocal process, to which the vocal ligaments attach.

(4) Arytenoid cartilages, along with the cricoid cartilage, make up the entire posterior surface of the larynx.

(1) Shaped like cones and are the smallest cartilages of the larynx.

(2) Articulate with the arytenoid cartilages on their superior surface, to which the corniculate cartilages are sometimes fused.

(3) When the larynx is viewed from above, the corniculate cartilages appear as two small elevations on the posteromedial aspect of the laryngeal inlet.

(1) Shaped like small, elongated clubs.

(2) Located lateral and anterior to the corniculate cartilages.

(3) When the larynx is viewed from above, the cuneiform cartilages appear as two small elevations just lateral and anterior to the corniculate cartilages.

(4) Housed in the aryepiglottic folds.

(5) The cuneiforms, along with the aryepiglottic folds, form the lateral aspect of the laryngeal inlet. The epiglottis forms the anterior aspect, and the corniculates form the posterior aspect of the laryngeal inlet.

6. Extrinsic ligaments of the larynx

a. Extrinsic ligaments attach cartilages of the larynx to structures outside the larynx.

b. The thyrohyoid membrane is a broad fibroelastic sheet that attaches the anterior and lateral superior aspects of the thyroid cartilage to the inferior surface of the hyoid bone (the posterior portion of the thyroid cartilage is attached to the hyoid bone by the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage).

c. The hyoepiglottic ligament is an elastic band that attaches the anterior surface of the epiglottis to the hyoid bone.

d. The cricotracheal ligament connects the lower portion of the cricoid cartilage to the trachea by a broad fibrous membrane.

7. Intrinsic ligaments of the larynx

a. Intrinsic ligaments attach cartilages of the larynx to one another.

b. The thyroepiglottic ligament attaches the inferior aspect of the epiglottis to the thyroid cartilage on its internal surface below the thyroid notch.

c. The aryepiglottic ligament attaches the arytenoid cartilages to the epiglottis and acts as a point of attachment for the aryepiglottic folds.

d. The cricothyroid ligament attaches the anterior portion of the thyroid cartilage to the anterior portion of the cricoid cartilage. It is through this ligament that an emergency cricothyroidotomy is performed.

e. The vocal ligament is a thick band that stretches from the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilages across the cavity of the larynx to attach to the thyroid cartilage just inferior to the thyroepiglottic ligament. The lateral borders of the vocal ligament attach to the inverted free borders of the cricothyroid ligament.

f. The ventricular ligament is a thick band that stretches from the arytenoid cartilage across the cavity of the larynx to the thyroid cartilage. It exists superior and lateral to the vocal ligament.

8. Cavity of the larynx (see Figure 4-6)

a. The larynx is divided into three sections by the pair of ventricular folds and vocal folds.

b. The upper section, the vestibule of the larynx, extends from the laryngeal inlet to the level of the ventricular folds.

(1) The ventricular folds are referred to as the false vocal cords.

(2) The space between the ventricular folds is the rima vestibuli.

c. The middle section, the ventricle of the larynx, extends from the ventricular folds to the vocal cords.

(1) The vocal folds are the true vocal cords.

(2) The space between the vocal folds is the rima glottidis or glottis.

(a) The glottis is triangular, the base being posterior and the apex anterior.

(b) It is the smallest opening of the adult airway (important when endotracheal tube size is selected).

(c) The dimensions of the glottis are smaller in women than in men.

(3) The size of the rima glottidis also is variable, depending on the state of the vocal cords (see Figure 4-6).

(a) Adduction is accomplished by medial rotation and approximation of the arytenoids, thus sealing the glottis.

(b) Abduction is accomplished by lateral rotation of the arytenoids, thus increasing the size of the glottis.

(4) The glottic or sphincter mechanism requires aryepiglottic folds, epiglottis, ventricular folds, and vocal folds to act in a coordinated fashion to seal the laryngeal inlet.

d. The lower section, the subglottic cavity of the larynx, extends from the vocal folds to the cricoid cartilage.

e. The epithelial lining of the larynx above the true vocal cords is continuous with the laryngopharynx and is stratified squamous epithelium (see Table 4-1).

f. The epithelial lining of the larynx below the true vocal cords is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium, the same as that in the trachea.

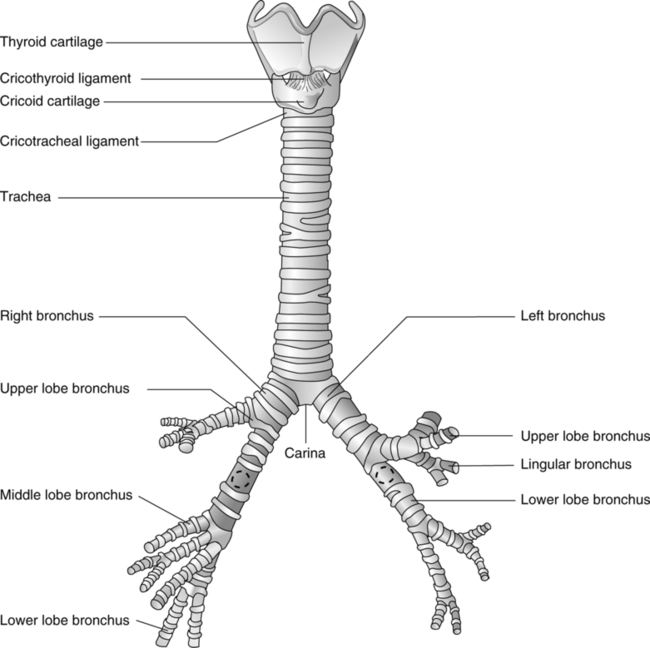

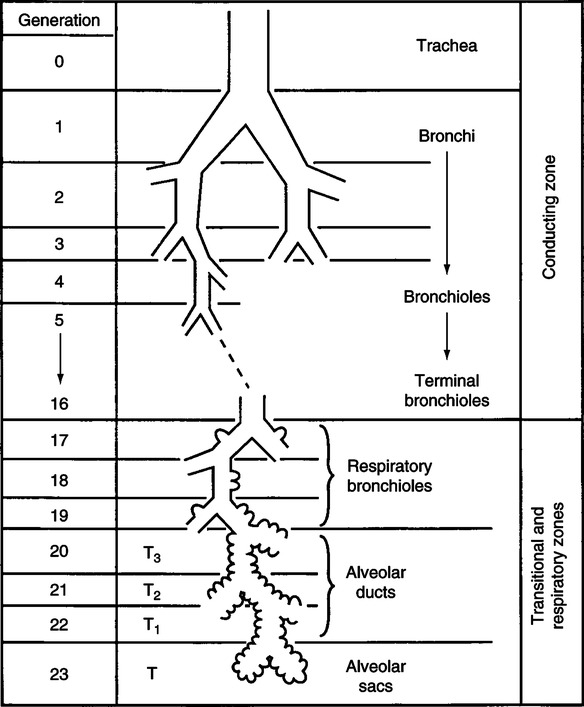

D Tracheobronchial tree and lung parenchyma (Figure 4-7)

1. The tracheobronchial tree functions in ventilation (to and fro movement of air) and is sometimes referred to as the conducting airway.

2. The lung parenchyma functions in external respiration and is the area of the lung where actual gas exchange occurs.

3. As the lower airway subdivides, it gives way to additional airway generations. Each new generation of airway is assigned a number. The numbering system below begins with assigning generation 0 to the trachea. The first branching or division of the trachea constitutes the mainstem bronchi, which are assigned generation 1. Each subsequent branching of the lower airway is assigned the subsequent generation number.

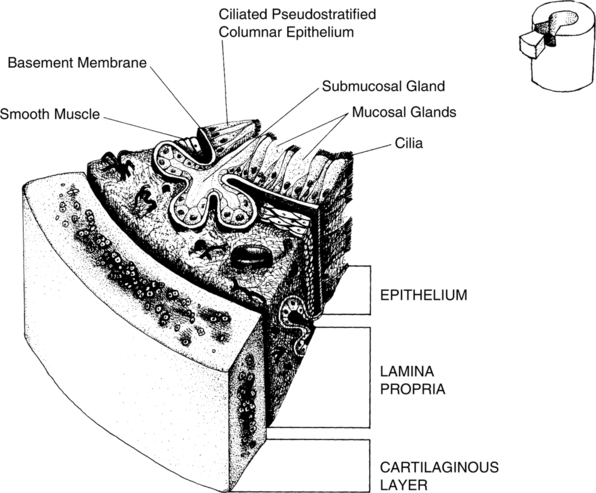

1. The trachea is a cartilaginous, membranous tube 10 to 13 cm in length and 2 to 2.5 cm in diameter.

2. The trachea extends from the cricoid cartilage at the sixth cervical vertebra to its point of bifurcation (carina) at the fifth thoracic vertebra.

3. Sixteen to 20 incomplete (C-shaped) cartilaginous rings open posteriorly and are arranged horizontally. The open ends of the cartilage and the area between individual cartilages are joined by a combination of fibrous, elastic, and smooth muscle tissue.

a. The smooth muscle is arranged longitudinally to shorten and elongate the trachea.

b. The smooth muscle also is arranged transversely to constrict and dilate the trachea.

4. The posterior wall of the trachea is separated from the anterior wall of the esophagus by loose connective tissue.

5. The trachea and following large airways (bronchi) contain three characteristic layers (Figure 4-8):

b. Lamina propria, which contains small blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, nerve tracts, elastic fibers, smooth muscle, and submucosal glands.

c. Epithelial, or intraluminal, layer, which is separated from the lamina propria by a noncellular basement membrane.

6. The epithelial lining of the trachea is continuous with the larynx above and consists of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (Table 4-2).

TABLE 4-2

Anatomical Comparison of Structures in the Lower Respiratory Tract

| Structure | Epithelium | Division |

| Larynx/below true cords | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | X |

| Trachea | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 0 |

| Mainstem bronchi | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 1 |

| Lobar bronchi | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 2 |

| Segmental bronchi | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 3 |

| Subsegmental bronchi | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 4-9 |

| Bronchioles | Pseudostratified ciliated columnar | 10-15 |

| Terminal bronchioles | Cuboidal to simple squamous | 16 |

| Respiratory bronchioles | Simple squamous | 17-19 |

| Alveolar ducts | Simple squamous | 20-22 |

| Alveolar sacs | Simple squamous | 23 |

| Alveoli | Type I; squamous | … |

| Type II; granular | … | |

| Type III; macrophage | … |

F Mainstem bronchi (generation 1)

1. The trachea bifurcates into two airways, the right and left mainstem bronchi, at the carina. The carina is generally located at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra.

2. A portion of mainstem bronchi is extrapulmonary (exists outside the lung in the mediastinum), but the majority of it is intrapulmonary (inside the lung proper).

3. The structural arrangement of the mainstem bronchi is the same as that of the trachea, with C-shaped pieces of cartilage, a lamina propria, and pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (see Figure 4-8).

4. The only structural difference between the mainstem bronchi and the trachea is that the intrapulmonary section of the mainstem bronchi is covered with a sheath of connective tissue, the peribronchiolar connective tissue.

a. The function of peribronchiolar connective tissue is to encase large nerve, lymphatic, and bronchial blood vessels as they follow the branchings of the subdividing airways.

b. The peribronchiolar connective tissue continues to follow the branching of the airways until the level of the bronchioles, where it disappears.

5. Mainstem bronchi are sometimes referred to as primary bronchi.

G Lobar bronchi (generation 2)

1. Five lobar bronchi correspond, respectively, to the five lobes of the lung.

2. The right mainstem bronchus trifurcates into the right upper, middle, and lower lobar bronchi.

3. The left mainstem bronchus bifurcates into the left upper and lower lobar bronchi.

4. The structural arrangement of lobar bronchi is the same as that of the mainstem bronchi (see Figure 4-8).

5. The epithelial lining of lobar bronchi is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (see Table 4-2).

6. Lobar bronchi are sometimes referred to as secondary bronchi.

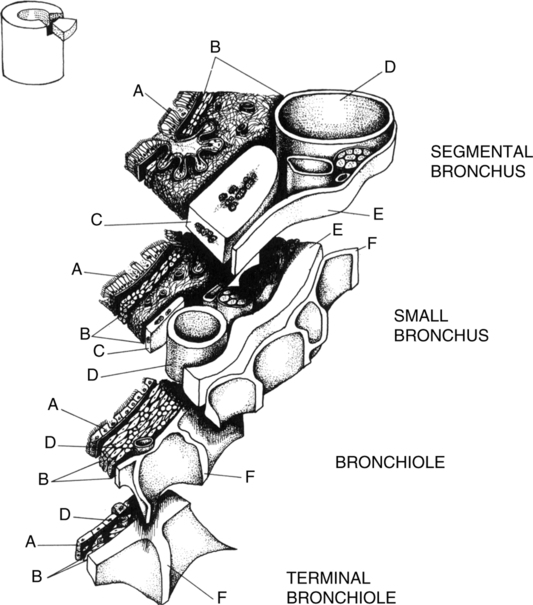

H Segmental bronchi (generation 3)

1. There are 18 segmental bronchi, corresponding to the 18 segments of the lung, with diameters of approximately 4.5 to 13 mm.

2. The structural arrangement of segmental bronchi is similar to that of lobar and mainstem bronchi, except that the C-shaped pieces of cartilage become less regular in shape and volume (Figure 4-9).

3. The epithelial lining of segmental bronchi is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium.

4. Segmental bronchi are sometimes referred to as tertiary bronchi.

I Subsegmental bronchi (generations 4-9)

1. The diameter of subsegmental bronchi ranges from 1 to 6 mm.

2. Cartilaginous rings give way to irregularly placed pieces of cartilage circumscribing the airway, the cartilaginous plaques (see Figure 4-9).

3. By the ninth generation of airways, cartilage is only scantily present.

4. As volume and regularity of cartilage have decreased from generation 0 to generation 9, so has the number of submucosal glands and goblet cells.

5. The epithelial lining of subsegmental bronchi is pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium.

J Bronchioles (generations 10-15)

1. Diameter is characteristically approximately 1 mm.

2. Cartilage is totally absent (see Figure 4-9).

3. Peribronchiolar connective tissue is absent; the lamina propria of these airways is directly embedded in surrounding lung parenchyma.

4. Airway patency is dependent not on the structural rigidity of surrounding cartilage but on fibrous, elastic, and smooth muscle tissue.

5. The epithelial lining of bronchioles is pseudostratified ciliated cuboidal epithelium (short squat cells as opposed to the elongated columnar cells).

K Terminal bronchioles (generation 16)

1. Average diameter is 0.5 mm and represents a cross-sectional area of approximately 116 cm2.

2. Goblet cells and submucosal glands disappear, although mucus is found in these airways (see Figure 4-9).

3. Cilia are absent from the epithelium of terminal bronchioles. This epithelium serves as a transition from the cuboidal epithelium of generation 15 to the squamous epithelium of generation 17.

4. Clara cells are located in the terminal bronchioles.

a. Plump columnar cells that bulge into the lumen of terminal bronchioles.

b. Probably responsible for production of mucus and surfactant found in terminal bronchioles.

5. Terminal bronchioles mark the end of the conducting airways; all airway generations distal to the terminal bronchioles are considered part of the lung parenchyma (Figure 4-10).

L Respiratory bronchioles (generations 17-19)

1. Average diameter is <0.5 mm with a cross-sectional area of approximately 1000 cm2.

2. Alveoli originate from the external surface of the respiratory bronchioles, where a small portion of external respiration takes place.

3. The epithelial lining of respiratory bronchioles is a low cuboidal epithelium interspersed with actual alveoli (simple squamous epithelium).

M Alveolar ducts (generations 20-22)

1. Alveolar ducts originate from respiratory bronchioles.

2. The only difference between alveolar ducts and respiratory bronchioles is that the walls of the alveolar ducts are totally made up of alveoli.

3. Approximately one half of the total number of alveoli originates from alveolar ducts.

N Alveolar sacs (generation 23)

1. Alveolar sacs are the last generation of airways and are blind passageways.

2. These appear functionally the same as alveolar ducts but differ because they form grapelike clusters having common walls with other alveoli.

3. The remaining half of alveoli originates from alveolar sacs.

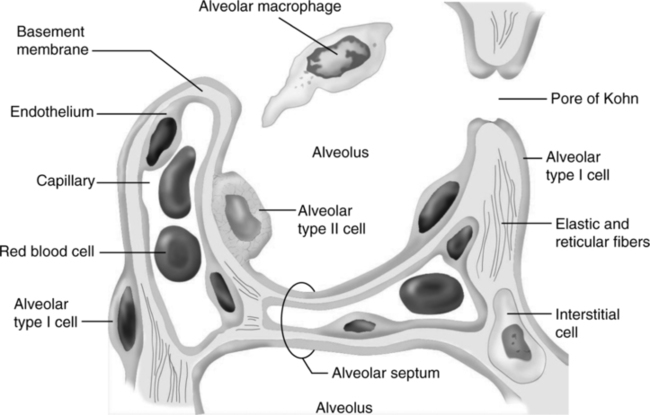

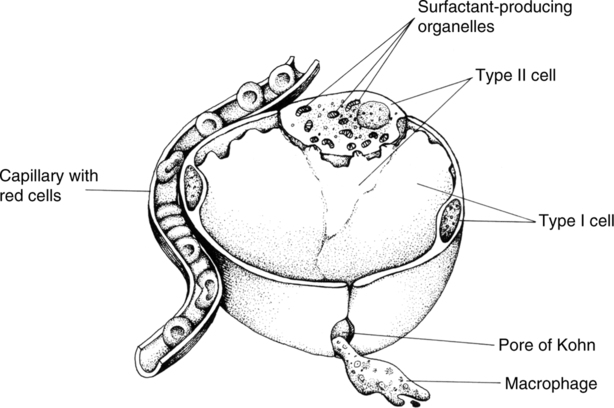

1. The alveoli are terminal air spaces that contain numerous capillaries in their septa, which serve as sites for gas exchange.

2. The average number of total alveoli contained in both lungs combined is 300 million but varies directly with the height of the individual and may be as many as 600 million.

3. The total cross-sectional area provided by the alveolar surface is approximately 80 m2.

4. The total cross-sectional area provided by the pulmonary capillaries is 70 m2, thus constituting an alveolar gas-pulmonary blood interface of 70 m2 (the size of a tennis court).

P Alveolar capillary membrane or alveolar septum (Figure 4-12)

1. The alveolar capillary membrane has four components: surfactant layer, alveolar epithelium, interstitial space, and capillary endothelium.

a. The surfactant is composed of a phospholipid attached to a lecithin molecule.

(1) Surfactant lines the internal alveolar surface.

(2) It reduces surface tension, facilitating inspiration and expiration.

b. Alveolar epithelium (simple squamous epithelium) is a continuous layer of tissue made up of type I and II cells lying on a basement membrane (see Table 4-2).

(1) Type I cells, or squamous pneumocytes: Flat, thin, simple squames making up 95% of alveolar surface.

(2) Type II cells, or granular pneumocytes: Plump, highly metabolic cells credited with surfactant production and alveolar repair.

(3) Type III cells, or alveolar macrophages: Free, wandering phagocytic cells that ingest foreign material on the alveolar surface.

c. The interstitial space is the area that separates the basement membrane of alveolar epithelium from the basement membrane of capillary endothelium.

(1) It contains interstitial fluid.

(2) This space may be so small, especially where diffusion is to take place, that the basement membranes appear fused.

d. Capillary endothelium is a continuous layer of tissue made up of flat, interlocking squames supported on a basement membrane.

2. Thickness of the alveolar capillary membrane varies from 0.35 to 1 μm.

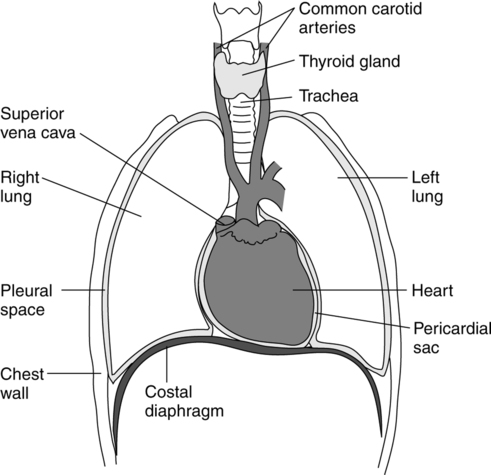

A The lungs are situated in the thoracic cavity separated by a structure (mediastinum) containing the heart, great vessels, esophagus, and trachea (Figure 4-13).

1. Each thoracic cavity is lined with a fine serous membrane, the parietal pleura, which also covers the dome of each hemidiaphragm.

2. The lung and each of its lobes are encased in a similar serous membrane called the visceral pleura.

3. A potential space (intrapleural space) between the two pleura contains a small amount of fluid called pleural fluid.

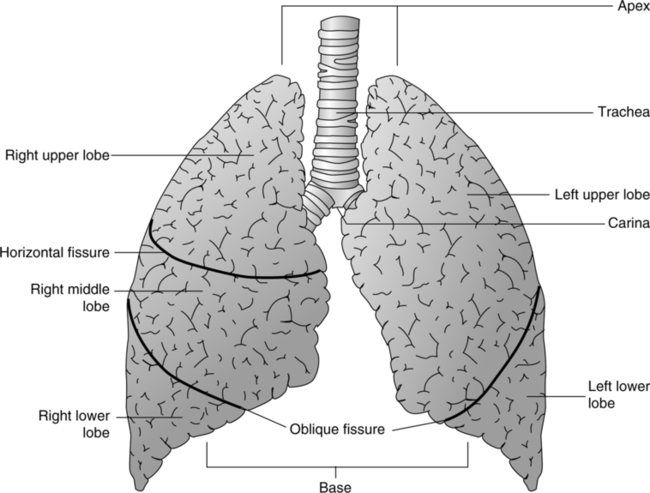

B The lung is a conical-shaped organ with four surfaces: apex, base, medial surface, and costal surface (Figure 4-14).

1. The apices are rounded superior sections of the lung. They extend 1 to 2 in. above the clavicles.

2. The bases are concave inferior surfaces of the lung. They rest on the hemidiaphragm. The right base lies higher in the thorax than the left to accommodate the large, underlying liver.

3. The medial surface of each lung exhibits a deep concavity to accept the heart and great vessels. This concavity is called the cardiac impression. The left cardiac impression is deeper than the right because the heart projects to the left of the midline.

4. The costal surface constitutes most of the lung surface in contact with the pleura lining the thoracic cavity.

C The root of the lung enters the lung proper at the hilum.

1. The root of the lung consists of a mainstem bronchus, a pulmonary artery, two pulmonary veins, major lymph vessels, and nerve tracts.

2. The hilum is the area where the root enters the lung. There the mediastinal and visceral pleura become continuous, forming the pulmonary ligament. This arrangement keeps the pleural cavity sealed and allows the root to enter the sealed lung.

D The right lung is divided into three lobes by the horizontal and oblique fissures (see Figure 4-14).

1. The oblique fissure isolates the right lower lobe from the right middle and right upper lobe.

2. The horizontal fissure divides the right upper lobe from the right middle lobe.

3. Externally the oblique fissure courses through the following landmarks:

a. Junction of the sixth rib and midclavicular line.

4. Externally the horizontal fissure courses through the following landmarks:

5. The right lung is larger than the left, and approximately 60% of gas exchange takes place in the right lung.

E The left lung is divided into two lobes by the oblique fissure.

1. The oblique fissure divides the left upper lobe from the left lower lobe.

2. Externally the left oblique fissure courses through the same landmarks as the right oblique fissure.

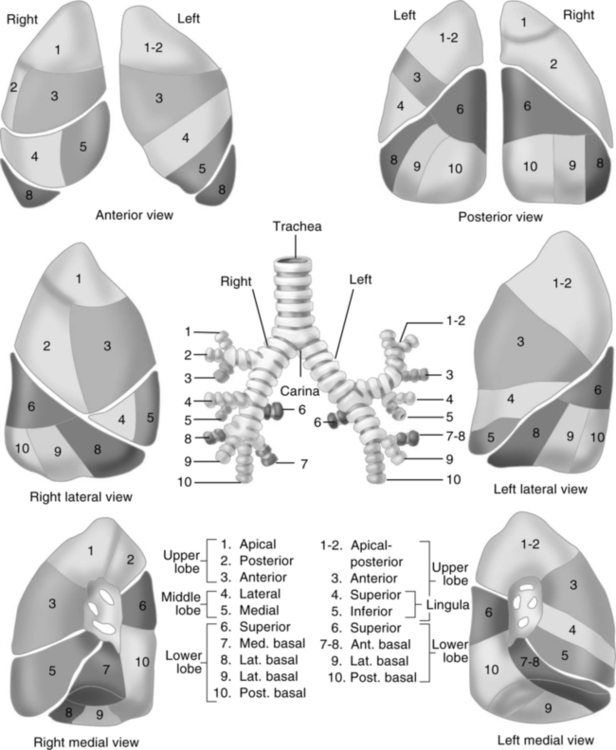

F The lobes of the lung are further subdivided into segments (Figure 4-15).

6. Knowledge of bronchopulmonary segmentation becomes important when postural drainage, auscultation, radiographic findings, and bronchoscopy are considered.

G The segments are further subdivided into secondary lobules.

1. Secondary lobules consist of a 15th-order airway (bronchiole) and its associated three to five terminal bronchioles and their distal respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs.

2. The secondary lobule is the smallest self-contained unit of the lung that is surrounded by connective tissue.

3. Secondary lobules appear as polyhedral masses observable on the lung surface and as dark intersecting lines between fissures.

4. Secondary lobules have their own discrete single pulmonary arteriole, venule, lymphatic, and nerve supply.

5. Secondary lobules are the building blocks of segments and are discernible on chest radiography.

6. Each secondary lobule comprises 30 to 50 primary lobules and measures 1 to 2.5 cm in diameter.

a. Primary lobules consist of a 19th-order respiratory bronchiole and every generation distal to it.

b. Primary lobules are not self-contained in connective tissue.

c. There are approximately 23 million primary lobules in the lung.

7. Secondary lobules may be important in isolating and maintaining disease locally. They also may be responsible for local matching of ventilation to perfusion.

H Bronchiolar and alveolar intercommunicating channels

1. The canals of Lambert, approximately 30 μm in size, provide collateral ventilation between primary lobules.

2. The pores of Kohn are interalveolar pores that allow collateral ventilation of alveoli. Their diameter varies from 3 to 13 μm.

3. A third channel connecting intersegmental respiratory bronchioles primarily in the lower lobes has been proposed, also providing collateral ventilation.

1. Afferent and efferent pathways of the autonomic nervous system innervate the lungs.

2. The afferent or sensory pathways originate in the epithelium of the bronchial walls, submucosa, interalveolar septa, and smooth muscles.

3. Parasympathetic fibers via the vagus nerves arranged in three groups of sensory fibers have been identified.

a. Pulmonary stretch receptors, which are slowly adapting.

(1) Located in smooth muscles of intrapulmonary airways.

(2) Stimulated by lung inflation or increased transpulmonary pressure.

c. C-fiber–pulmonary type J receptors

(1) Located in alveolar walls, airways, and blood vessels.

(4) Efferent or motor pathways reach the lung through the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.

(5) The sympathetic fibers terminate in the airway walls, vascular smooth muscle, and submucosal glands; stimulation causes:

(6) Stimulation of the parasympathetic motor fibers in the airways causes:

1. The metabolic needs of the airways are provided by the bronchial arteries, which originate from the aorta or the upper intercostal arteries.

2. These vessels accompany the bronchial tree down to the terminal bronchioles.

3. Structures distal to the terminal bronchioles are believed to obtain their nutrients from the mixed venous blood of the pulmonary circulation.

4. The bronchial circulation is approximately 1% to 2% of the cardiac output.

5. A portion of the venous blood from the capillaries of the bronchial circulation returns to the right heart by way of the:

6. The remainder of the bronchial circulation returns to the left heart by way of the:

7. Blood emptying into the left heart is termed venous admixture.

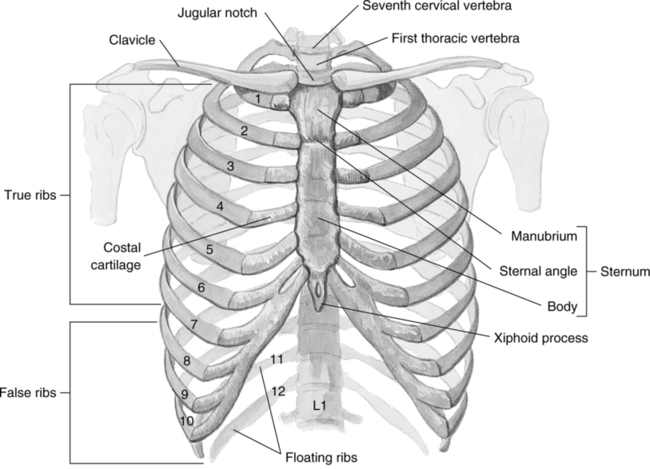

A It is a bony and cartilaginous frame within which lie the principal organs of circulation and respiration.

B It is conical and narrow above and broad below.

C Posteriorly, the thorax includes the 12 thoracic vertebrae and the posterior portion of the ribs.

D Laterally, the thorax is convex and formed by the ribs.

E Anteriorly, it is composed of the sternum, anterior ends of the ribs, and the costal cartilage.

F The superior opening into the thorax—defined by the manubrium, first rib, and first thoracic vertebra—is called the thoracic inlet or operculum.

G The inferior opening out of the thorax—defined by the 12th rib, costal cartilage of ribs 7 through 10, and 12th thoracic vertebra—is called the thoracic outlet.

H Functions of the bony thorax are to protect underlying organs, aid in ventilation, and provide a point of attachment for various bones and muscles.

1. The sternum is approximately 17 cm long.

2. The sternum is divided into three sections:

3. The manubrium articulates with the clavicle and the first and second ribs.

4. The junction of the manubrium and the body is called the angle of Louis. The trachea bifurcates beneath this junction.

5. The body of the sternum articulates with ribs 2 through 7.

1. Twelve elastic arches of bone, posteriorly connected to the vertebral column.

2. Types of ribs: True, false, and floating.

b. Called vertebrosternal ribs because they connect to the sternum via costal cartilage and the vertebrae of the spinal column.

b. Called vertebrocostal ribs because they connect to costal cartilage of superior rib and the vertebrae of the spinal column.

6. The space between the ribs is called the intercostal space.

7. All 12 pairs of ribs are positioned in an inferior direction. Contraction of the intercostal muscles elevates the ribs from their natural inclined position.

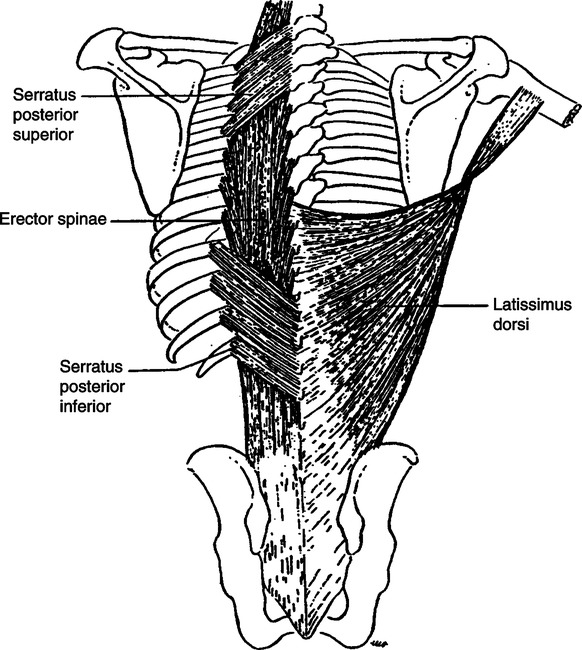

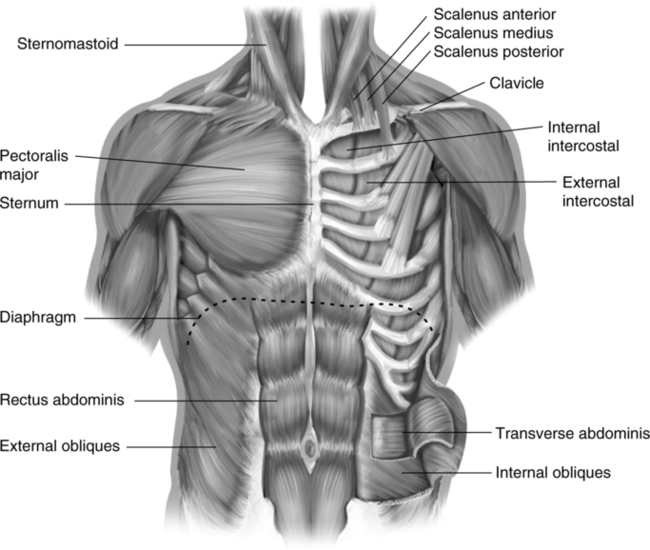

V Muscles of Inspiration (Figure 4-17)

A The diaphragm, external intercostal, parasternal intercostal, and scalene muscles are normally used for resting inspiration (Table 4-3).

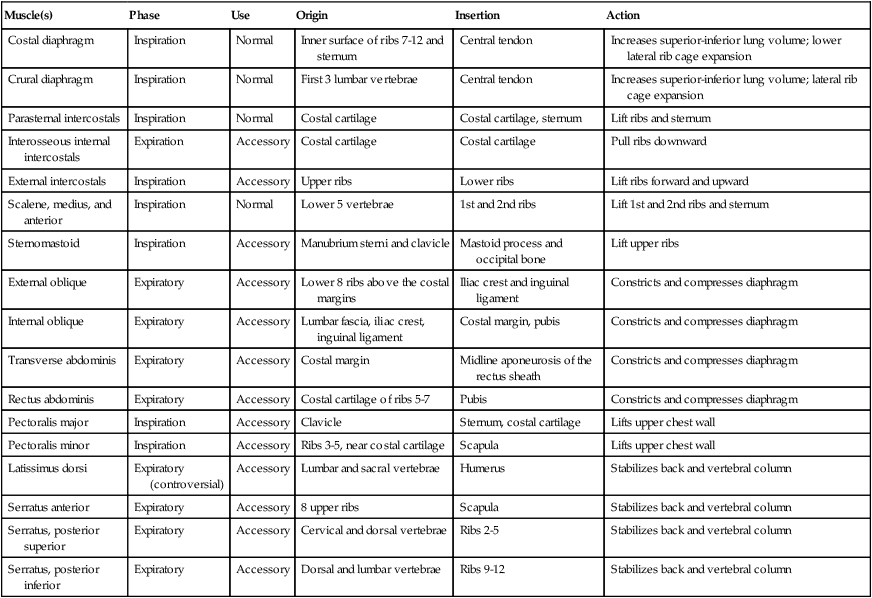

TABLE 4-3

| Muscle(s) | Phase | Use | Origin | Insertion | Action |

| Costal diaphragm | Inspiration | Normal | Inner surface of ribs 7-12 and sternum | Central tendon | Increases superior-inferior lung volume; lower lateral rib cage expansion |

| Crural diaphragm | Inspiration | Normal | First 3 lumbar vertebrae | Central tendon | Increases superior-inferior lung volume; lateral rib cage expansion |

| Parasternal intercostals | Inspiration | Normal | Costal cartilage | Costal cartilage, sternum | Lift ribs and sternum |

| Interosseous internal intercostals | Expiration | Accessory | Costal cartilage | Costal cartilage | Pull ribs downward |

| External intercostals | Inspiration | Accessory | Upper ribs | Lower ribs | Lift ribs forward and upward |

| Scalene, medius, and anterior | Inspiration | Normal | Lower 5 vertebrae | 1st and 2nd ribs | Lift 1st and 2nd ribs and sternum |

| Sternomastoid | Inspiration | Accessory | Manubrium sterni and clavicle | Mastoid process and occipital bone | Lift upper ribs |

| External oblique | Expiratory | Accessory | Lower 8 ribs above the costal margins | Iliac crest and inguinal ligament | Constricts and compresses diaphragm |

| Internal oblique | Expiratory | Accessory | Lumbar fascia, iliac crest, inguinal ligament | Costal margin, pubis | Constricts and compresses diaphragm |

| Transverse abdominis | Expiratory | Accessory | Costal margin | Midline aponeurosis of the rectus sheath | Constricts and compresses diaphragm |

| Rectus abdominis | Expiratory | Accessory | Costal cartilage of ribs 5-7 | Pubis | Constricts and compresses diaphragm |

| Pectoralis major | Inspiration | Accessory | Clavicle | Sternum, costal cartilage | Lifts upper chest wall |

| Pectoralis minor | Inspiration | Accessory | Ribs 3-5, near costal cartilage | Scapula | Lifts upper chest wall |

| Latissimus dorsi | Expiratory (controversial) | Accessory | Lumbar and sacral vertebrae | Humerus | Stabilizes back and vertebral column |

| Serratus anterior | Expiratory | Accessory | 8 upper ribs | Scapula | Stabilizes back and vertebral column |

| Serratus, posterior superior | Expiratory | Accessory | Cervical and dorsal vertebrae | Ribs 2-5 | Stabilizes back and vertebral column |

| Serratus, posterior inferior | Expiratory | Accessory | Dorsal and lumbar vertebrae | Ribs 9-12 | Stabilizes back and vertebral column |

From Pierson DJ, Kacmarek RM: Foundations of Respiratory Care. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1992. Churchill Livingstone

1. Diaphragm: Dome-shaped muscle that separates the thoracic from the abdominal cavity.

a. It is the major muscle of ventilation.

b. It is composed of two parts:

c. When standing, the dome of the diaphragm at functional residual capacity (FRC) on the right is located at the eighth thoracic vertebra and at the ninth thoracic vertebra on the left.

d. During normal breathing the diaphragm moves 1.0 to 1.7 cm and may descend as much as 10 cm during stress.

e. Normally at FRC part of the diaphragm lies along the rib cage (zone of opposition).

f. Innervation: Cervical spinal motor nerves 3, 4, and 5 (phrenic nerve).

a. External and internal intercostal muscles are located between all ribs.

b. The internal muscle is composed of two separate muscles:

(1) Parasternal: An inspiratory muscle.

(2) Interosseous or internal intercostal muscle: An expiratory muscle.

c. External intercostal: An inspiratory muscle.

d. Innervation: Thoracic spinal motor nerves 1 through 11.

e. These muscles prevent the intercostal space from bulging and recessing with normal ventilatory efforts.

B Accessory muscles of inspiration

1. Each tends to perform one of two actions, either raising the thorax or stabilizing the thorax so that other muscles can effectively raise the thorax.

2. It should be noted that use of accessory muscles for resting inspiration is abnormal and that accessory muscle use should occur only with deep or forced inspiration.

VI Accessory Muscles of Expiration (see Figures 4-17 and 4-18)

A There are no muscles of quiet resting expiration. Expiration is purely a passive process brought about by the normal elastic tendencies of the lung coupled with cessation of inspiratory muscle contraction. Therefore, any muscles used for expiration are termed accessory muscles of expiration.

B Any muscle usage for quiet resting expiration is abnormal.

C Accessory muscles of expiration are used only for forced expiration, making expiration an active process.

D The accessory muscles of expiration are of the back, thorax, or abdomen and tend to either pull the thorax down or support the thorax so that other muscle groups can effectively pull down on the thorax.

VII Other Functions of the Lung

A Blood reservoir for the left ventricle.

1. Approximately 600 ml is maintained in the lung.

2. This volume is sufficient to maintain several cardiac cycles in the face of decreased venous return.

B The pulmonary circulation acts as a filter for the systemic circulation. Particles are trapped before they can enter the systemic circulation.