Applied anatomy of the cervical spine

The anatomy of the cervical spine is complex and unique. To understand the diagnosis and treatment of the multiple disorders affecting this vital region, a thorough knowledge of the anatomy is necessary.

Bones

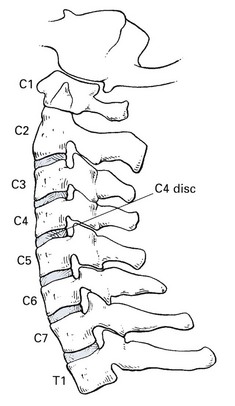

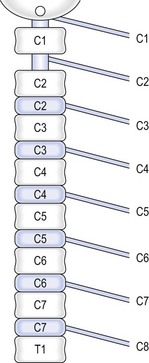

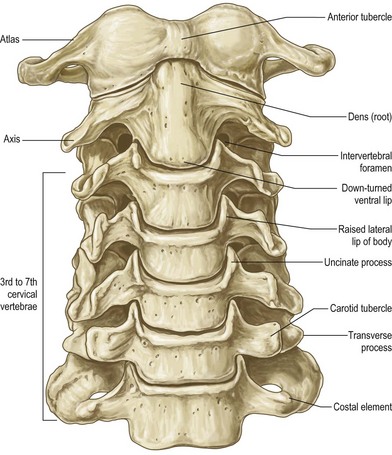

The cervical spine has seven vertebrae, which may be divided into two groups that are distinct both anatomically and functionally: the upper pair (C1 and C2, the atlas and axis) and the lower five (C3–C7) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Anterior view of the cervical spine. From Standring, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009 with permission.

Upper cervical spine

The upper cervical spine has the first and second vertebrae – the atlas and axis – and forms a unit with the occiput.

The atlas

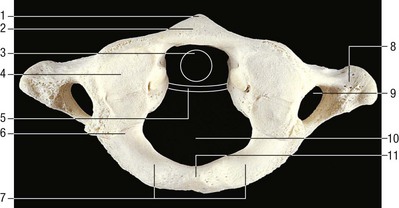

The atlas (Fig. 2) does not have a vertebral body – this has been absorbed into the axis vertebra, to form the odontoid process (Fig. 3). A thick anterior arch remains, extending into and joining the two lateral masses, on which are the superior atlantal joint facets, which articulate with the occipital condyles; and the inferior joint facets of the axis. The posterior arch is thinner than the anterior arch and forms the posterior junction of the lateral masses. The large vertebral foramen thus formed has a larger diameter in the transverse than in the sagittal plane.

Fig 2 The atlas, superior view. 1, Anterior tubercle; 2, anterior arch; 3, outline of the dens; 4, superior articular facet; 5, outline of transverse ligament; 6, groove for cervical artery and C1; 7, posterior arch; 8, transverse process; 9, foramen transversum; 10, vertebral foramen; 11, posterior tubercle. From Standring, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009 with permission.

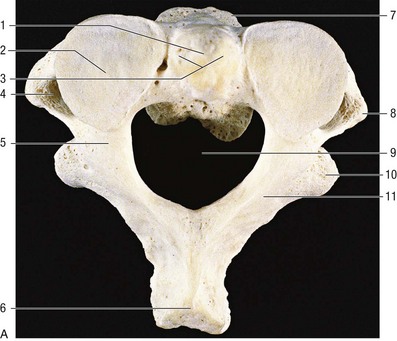

Fig 3 (A) Axis, superior view. 1, Dens – attachment of apical ligaments; 2, superior articular facet; 3, dens – attachment of alar ligaments; 4, foramen transversum; 5, pedicle; 6, spinous process; 7, body; 8, transverse process; 9, vertebral foramen; 10, inferior articular process; 11, lamina. (B) Axis, lateral aspect. 1, Dens – attachment of alar ligaments; 2, dens – facet for the anterior arch of the atlas; 3, groove for transverse ligament of atlas; 4, superior articular facet; 5, lateral mass; 6, divergent foramen transversum; 7, body; 8, ventral lip of body; 9, lamina; 10, spinous process; 11, inferior articular facet; 12, transverse process. From Standring, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009 with permission.

The transverse processes contain a transverse foramen through which the vertebral artery passes before it loops back above the upper surface of the posterior arch, which sometimes contains an arterial groove, although anatomical anomalies are frequently encountered.

The posterior aspect of the anterior arch has a facet for articulation with the odontoid process of the axis, which is held in place by the transverse ligament, spanned between two tubercles, which project from the inner sides of the lateral masses.

The axis

The second cervical vertebra is the axis (Fig. 3). Its vertebral body is formed by fusion with the vertebral body of the atlas to form the odontoid process (or dens), which is completely separate from the atlas. The laminae of the axis are very well developed and blend into a bifid spinous process.

Both transverse processes have a transverse foramen for the vertebral arteries. The superior articular facets of the axis articulate with the inferior articular facets of the atlas. The inferior articular facets of the axis articulate with the superior articular facets of the third vertebra.

Lower cervical spine

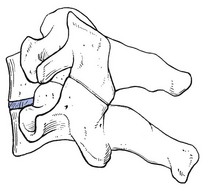

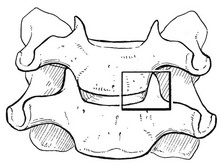

The lower cervical spine is composed of the third to the seventh vertebrae which are all very similar. Each vertebral body is quite small (Fig. 4). Its height is greater posteriorly than anteriorly and it is concave on its upper aspect and convex on its lower. On its upper margin it is lipped by a raised edge of bone. The anteroinferior border of the vertebral body projects over the anterosuperior border of the lower vertebra.

Fig 4 Seventh cervical vertebra, superior view. 1, Body; 2, superior articular process; 3, inferior articular process; 4, spinous process; 5, uncinate process; 6, foramen transversum; 7, transverse process; 8, pedicle; 9, vertebral foramen; 10, lamina. From Standring, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009 with permission.

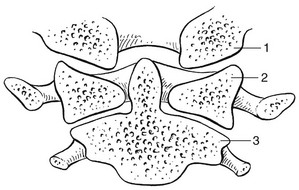

Anterolateral (in the upper vertebrae) to posterolateral (in the lower vertebrae) on the upper surface of the body, two uncinate processes project upwards and articulate with the lower notches (or anvils) of the upper vertebra to form the joints of von Luschka or uncovertebral joints.

Laterally, the transverse processes have an anterior and a posterior tubercle, which are respectively the remnants of an embryonic rib and transverse process. The spinal nerve lies in the groove between the two tubercles. The transverse process also has a transverse foramen for the vertebral artery and vein. This is not so at C7, where the foramen encloses only the accessory vertebral vein.

The intervertebral foramina are between the superior and inferior pedicles. The articular processes for the articulation with the other vertebrae are more posterior. The two laminae blend together in a bifid spinous process (at C3, C4 and C5).

The spinous processes of C6 and C7 are longer and taper off towards the ends. C7 has a large spinous process and is, therefore, called the vertebra prominens.

Intervertebral discs

There are six cervical discs, because there is no disc between the upper two joints. The first disc is between the axis (C2) and C3. From this level downwards to the C7–T1 joint they link together and separate the vertebral bodies. Each is named after the vertebra that lies above: e.g. the C4 disc is the disc between the C4 and C5 vertebrae (Fig. 5).

The disc, comprised of an annulus fibrosus, a nucleus pulposus and two cartilaginous endplates, has the same functions as the lumbar disc, and so will not be discussed in detail (see Ch. 31, Applied Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine). There are, however, some differences (Table 1). At the cervical spine the discs are more effectively within the spine than they are at the thoracic or lumbar levels because of the superior concavity and inferior convexity of each vertebral body. They are also about one-third thicker anteriorly than posteriorly, which gives the cervical spine a lordotic curve that is not related to the shape of the vertebral bodies. The annulus fibrosus is also thicker in its posterior part than it is in the lumbar spine. The further down the spine, the more the nucleus pulposus lies anteriorly in the disc, and it disappears earlier in life than it does in the lumbar spine. For both these reasons, nuclear disc prolapses are uncommon after the age of 30.

Table 1

Differences between the cervical and lumbar discs

| Cervical | Lumbar |

| Contained by vertebral bodies | Not contained by vertebral bodies |

| Thicker anteriorly than posteriorly | Equal height |

| Annulus thicker posteriorly | Annulus weaker posteriorly |

| Nucleus in anterior part of disc | Nucleus in posterior part of disc |

Joints

The cervical spine is more mobile than the thoracic or lumbar. Its structure allows movements in all directions, although not every level contributes to all movements.

Occipitoatlantoaxial joints

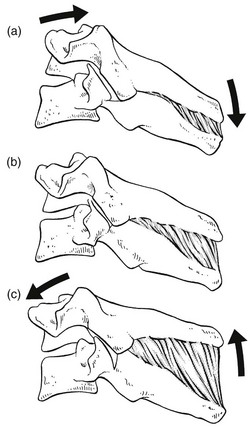

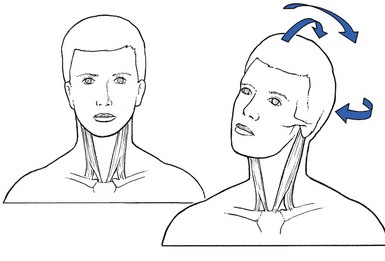

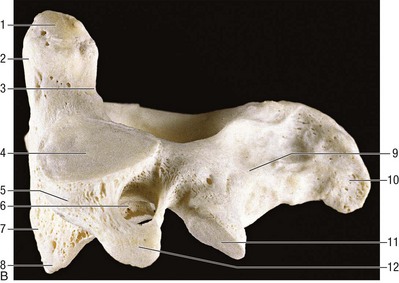

The occipital condyles are arcuate in the sagittal plane and fit into the cup-shaped superior articular surfaces of the atlas (Fig. 6). These joints only allow moderate flexion–extension (13–15°) and lateral flexion (3–8°) movements (Fig. 7). Axial rotation is not possible at these joints.

Fig 7 The occipitoatlantoaxial joint and its movements: (a) flexion, (b) extension, (c) lateral flexion.

At the joint between C1 and C2 extensive rotation movement is possible (45–50°) which represents about 50% of rotation in the neck (Fig. 8). There is a moderate flexion–extension excursion (10°) but lateral flexion is impossible.

Joints between C2 and C7

Most flexion–extension takes place at the joints C3–C4, C4–C5 and especially C5–C6. Lateral flexion and axial rotation occur mainly at C2–C3, C3–C4, C4–C5.

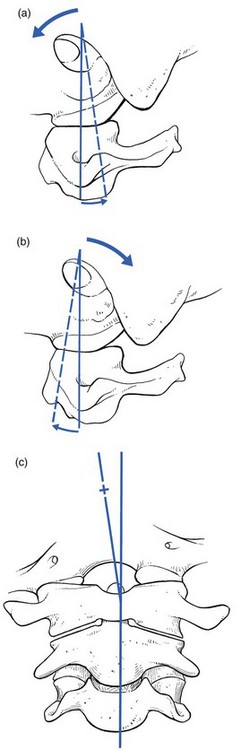

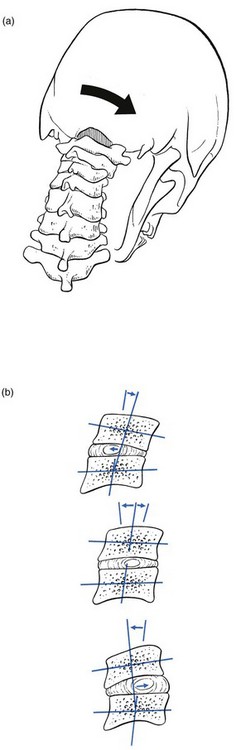

Mobility is less in the most caudal segments and coupling of movements is present (Fig. 9a). This phenomenon is the result of the position of the articular surfaces of the facet joints (see p. 123). Lateral flexion is always combined with ipsilateral rotation. So, for example, lateral flexion to the left is accompanied by rotation to the left. This is greatest at C2–C3 and coupling rotation decreases towards the caudal aspect of the spine. The clinical importance of this becomes clear during examination: specific articular patterns may occur as its result.

Fig 9 Combined flexion and rotation in the lower cervical spine (a), and lateral view of disc movements (b), upper: extension; middle: neutral position; lower: flexion.

Movement takes place at two sites. First, in the anterior part of the lower cervical spine, which contains the intervertebral joints (with their intervertebral discs) and the uncovertebral joints and, second, in the posterior part where the facet joints, the arches and the transverse and spinous processes are found.

Anterior aspect

Intervertebral joints

The intervertebral joint is the complex of two vertebral bodies and the intervertebral disc between them (Fig. 10). The disc has several functions: it permits greater mobility between the vertebrae; it helps distribute weight over the surface of the vertebral body during flexion movements; and it acts as a shock absorber during axial loading. The joints are mainly stabilized by the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments and the uncovertebral joints.

Uncovertebral joints (Fig. 11)

These develop during childhood when fissuring occurs in the lateral aspect of the intervertebral disc, leading to the formation of a cleft in the adult spine. They do not contain articular cartilage or synovial fluid and must therefore be considered as pseudojoints, although they do undergo degenerative changes. These secondary ‘joints’ add to lateral stability.

Posterior aspect and facet joints

Posteriorly the vertebrae are held together by the ligaments between the spinous processes (ligamentum nuchae and interspinous ligaments) and between the laminae (ligamentum flavum), and they articulate via the facet joints.

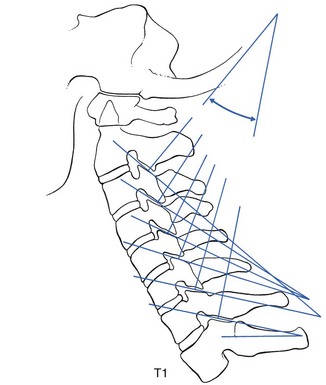

The facet joints are classified as diarthrodial joints: the articular surfaces are covered with cartilage; there is a synovial membrane and a fibrous joint capsule with contained synovial fluid. The joint line is oblique: it courses from anterosuperior to posteroinferior, along an angle of 45° at the level C2–C3, which decreases to 10° at C7–T1 (Fig. 12). Because the joint line is oblique and the capsule is lax, more movement is possible than at the thoracic and lumbar levels.

Fig 12 The facet joints, showing the decrease of the obliquity of the joint line towards the lower part of the spine.

Rotation is always combined with ipsilateral side flexion. During rotation to the left the lower facet of the upper vertebra at the left side glides backward on the upper facet of the vertebra below. The opposite happens at the right.

During extension of the neck, the vertebral body of the upper vertebra glides backwards (Fig. 13a). The lower facets not only glide backwards and downwards but also tilt backwards, which results in opening in front and closing behind. The reverse happens during flexion: the lower facets of the upper vertebra glide forwards and upwards and tilt forwards, which opens the joint at the back and closes it in front (Fig. 13c).

Ligaments

The cervical spine has a complex ligamentous system. Ligament function is to maintain normal osseous relationships. Clinically, however, they are not so important because ligamentous lesions in the cervical spine are not that common and, when they occur, it is difficult to find out where exactly the problem lies.

Two distinct sets of ligaments can be recognized: the ligaments of the occipitoatlantoaxial complex and those of the lower cervical spine.

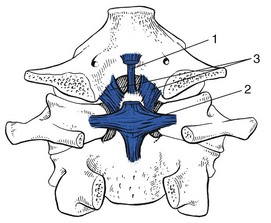

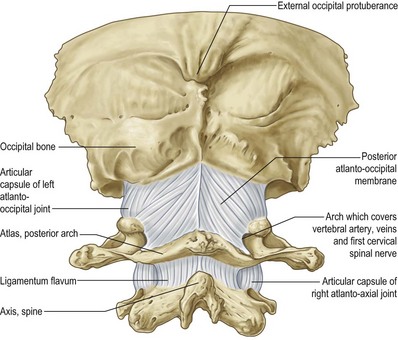

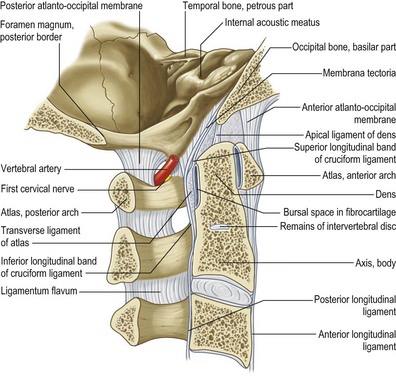

Ligaments of the occipitoatlantoaxial complex

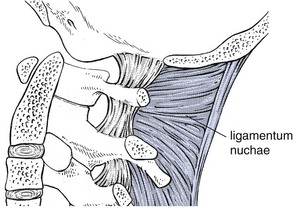

These are strong structures that stabilize the upper cervical spine. First, there are the ligaments connecting the occiput to atlas and axis: the anterior atlanto-occipital membrane, the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane and the tectorial membrane (Fig. 14). A second ligamentous complex connects the axis to the occiput: the apical ligament, the longitudinal component of the cruciform ligament and the alar ligaments (Fig. 15). Third, there is the complex of ligaments that connect axis to atlas: the lateral component of the cruciform ligament (the transverse ligament), the two accessory atlantoaxial ligaments and the ligamentum flavum (Fig. 16). Finally, the ligamentum nuchae (Fig. 17) is attached above to the external occipital protuberance, lies in the sagittal plane and merges with the interspinous ligaments and supraspinous ligament, which becomes an individual ligament from the spinous process of C7 downwards. This ligament contains much elastic tissue and is stretched during neck flexion. Because of its elasticity it helps to bring the head back into the neutral position.

Fig 14 Occipitoantlantoaxial complex: posterior view and sagittal section. From Standring, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009 with permission.

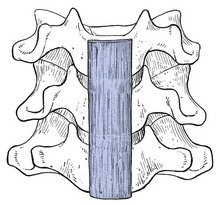

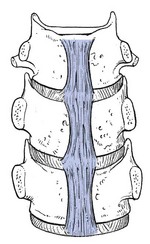

Ligaments of the lower cervical spine

The anterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 18) is closely attached to the vertebral bodies, but not to the discs. By contrast the posterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 19) is firmly attached to the disc and is wider in the upper cervical spine than in the lower. Both ligaments are very strong stabilizers of the intervertebral joints. The lateral and posterior bony elements are connected by the ligamentum flavum, the intertransverse ligaments and interspinous ligaments and the supraspinous ligament (Fig. 20).

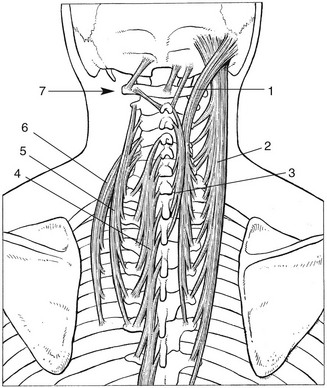

Muscles

Muscular action at the cervical spine is dependent on a combination of activities of a great number of muscles and whether or not they contract bilaterally or unilaterally. There are three functional groups: flexors; extensors; and rotators and lateral flexors.

Most muscles do not have clinical importance, in that lesions of them hardly ever occur. However, they can sometimes indirectly involve other (non-contractile) structures. On examination a resisted movement (muscular contraction) or a passive movement (whereby the muscle is stretched) may influence a lesion lying outside the muscle in, for example, an inert tissue. One contractile structure makes an exception however: an acute lesion of the longus colli causes, besides pain and weakness on flexion, serious limitations of extension and both rotations (see Standring, Fig. 28.6).

It should be noted that the function of many of the muscles is multiple and depends on the mode of action employed. For example, bilateral action of the sternocleidomastoids is involved in flexion–extension, but unilateral action results in ipsilateral lateral flexion and contralateral rotation (see Fig. 24).

Unilateral action of the flexors results in either pure rotation or lateral flexion, or a combination of both, sometimes ipsilaterally and sometimes contralaterally.

Many of the extensor muscles have other functions as well as extension, the latter occurring when they act bilaterally.

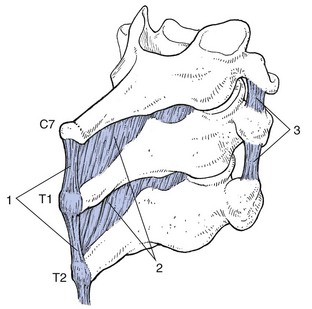

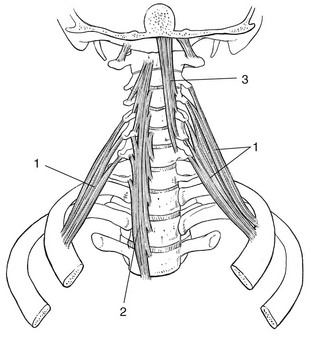

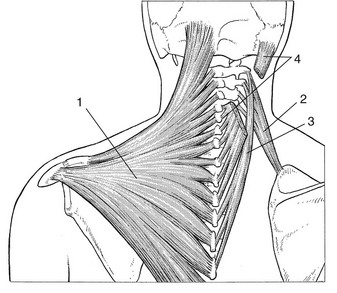

The muscles of the neck are illustrated in Figures 21–

.

Fig 22 Superficial extensor muscles: 1, trapezius; 2, levator scapulae; 3, splenius cervicis; 4, splenius capitis.

Nervous structures

Related structures

Spinal canal

In the cervical spine, the spinal canal is commodious compared to that of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Its outline is oval in the transverse plane and the average anteroposterior diameter is 17 mm, although this varies with movement: flexion increases it and extension decreases it. During extension there is a backward movement of the upper vertebra in relation to the lower because of the obliquity of the facet joints (Fig. 13). As the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal cord at midcervical level is about 10 mm, there is, however, a large margin of safety.

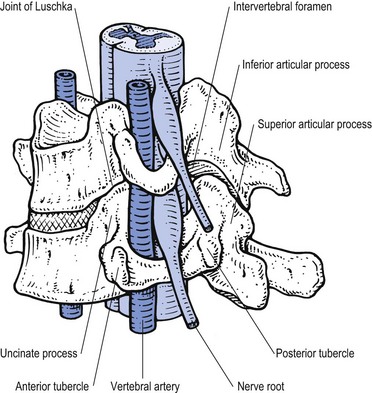

Intervertebral foramen

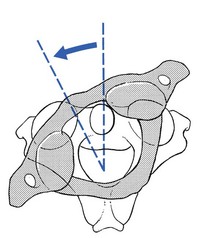

The intervertebral foramen lies between adjacent pedicles and through it the spinal nerve emerges from the spinal canal (Fig. 25). The foramen continues across the bifid transverse process and is orientated anterolaterally 45° and anterocaudally 15°. The anterior border is the uncinate process and vertebral body and the articular facet is posterior. The diameter of the foramen is reduced during a combined movement of extension and ipsilateral rotation.

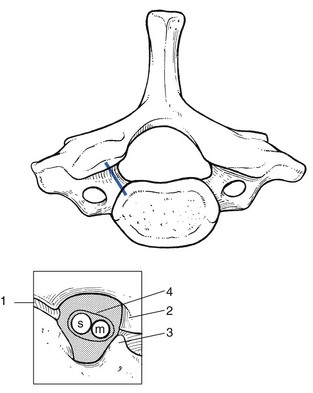

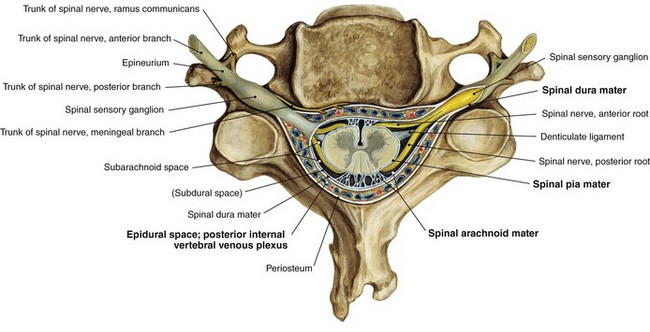

Spinal membranes

The dura mater is firmly attached to the rim of the foramen magnum and its fibres blend with the periosteum within the skull. In the spinal canal it is not attached to the vertebral arches, because of the presence of protective fat tissue in between. The arachnoid is a membrane which lies in close contact with the dura. The subarachnoid space is quite wide. The third layer, the pia mater, covers the spinal cord (Fig. 26). A number of dentate ligaments pass between a fold of the pia mater which extends longitudinally and the anterior and posterior nerve roots. These ligaments are attached to the dura and suspend the spinal cord in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Fig 26 The dura mater and exits from the spinal canal; cross-section at the level of the fifth cervical vertebra. From Putz, Sobotta – Atlas of Human Anatomy, 14th edn. Urban & Fischer/Elsevier, Munich, 2008 with permission.

Mobility of the dura mater

The dura mater can move considerably without influence on the cord. This is an interesting feature, in that the cervical spine lengthens approximately 3 cm during neck flexion. Consequently the dura mater, attached above and below, migrates within the spinal canal. It thus moves forwards and can be dragged against any space-occupying lesion within the canal (e.g. a disc protrusion). As a consequence the mobility of the dura can be hindered, increasing tension and resulting in pain, because the dura is also sensitive.

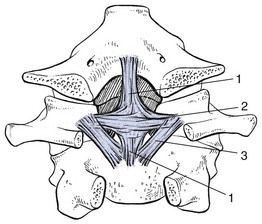

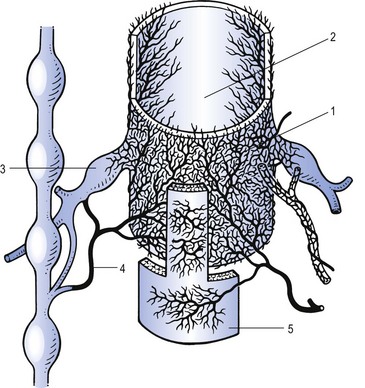

Sensitivity of the dura mater

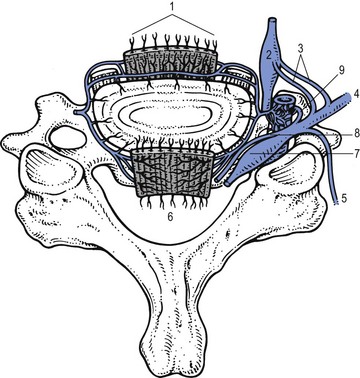

The anterior aspect of the dura mater is innervated by a dense longitudinally orientated nerve plexus consisting of different fibres of the sinuvertebral nerves originating at several levels (Fig. 27). Distal to the spinal ganglion, the sinuvertebral nerve detaches and passes back into the spinal canal to innervate the posterior longitudinal ligament, the anterior aspect of the dural sac and the dural sheath around the nerve root, the anterior capsule of the facet joints and also the vascular structures (Fig. 28).

Fig 27 The sinuvertebral nerve and its related structures: 1, anterior longitudinal ligament; 2, sympathetic trunk; 3, rami communicantes; 4, ventral ramus of spinal nerve; 5, dorsal ramus of spinal nerve; 6, posterior longitudinal ligament; 7, spinal ganglion; 8, anterior root; 9, sinuvertebral nerve.

Fig 28 The anterior part of the dura mater is innervated by a mesh of nerve fibres belonging to different and consecutive sinuvertebral nerves: 1, anterior part of the dura; 2, posterior part of the dura; 3, spinal ganglion of nerve root; 4, sinuvertebral nerve; 5, posterior longitudinal ligament.

This could be an explanation for the ‘dural pain’ that occurs when the anterior part of the dura is compressed (see p. 16). The pain is multisegmental, which means it is felt in several dermatomes at a time.

The mobility and sensitivity of the dura mater are described in detail on page 425.

Nerve roots

The nerve root contains motor and sensory branches formed by the convergence of rootlets emerging from the ventral and dorsal aspect of the spinal cord. The branches remain completely separated until their fusion in the spinal ganglion – sensory above and motor below – but are surrounded by the continuation of the dura – the dural sheath. Just outside the intervertebral foramen the root divides into a dorsal and ventral branch – the dorsal ramus and the ventral ramus, the latter joined by the cervical sympathetic chain.

The dural sheath

The dural investment surrounds the nerve root from the point where it leaves the spinal cord to the lateral border of the intervertebral foramen (Fig. 26). It is sensitive and slightly mobile, which means that some migration is possible.

The parenchyma

Irritation of the parenchyma, for instance as the result of external pressure, results in paraesthesia. This is also segmental and felt in the same dermatome as the ‘dural sheath pain’. Further irritation and destruction of the neural fibres lead to impaired conduction, which results in motor and/or sensory deficit.

Except for the nerve roots C6 and C7, which are slightly more oblique, the course of the root is almost directly lateral and thus horizontal, in contrast to the oblique course found in the lumbar spine. There are eight cervical nerve roots. The C1 root emerges between occiput and atlas, and the nerve root C8 between the seventh cervical and the first thoracic vertebrae. The result of this is that, for instance, a nerve root C7 can only become compressed by the disc C6 (the disc between the vertebrae C6 and C7) (Fig. 29).

Innervation of the cervical spine

That part of the cervical spine which lies anterior to the plane of the intervertebral foramina is innervated by the anterior primary rami and their branches – the sinuvertebral nerves. The posterior aspect of the spine is innervated from the posterior primary rami.

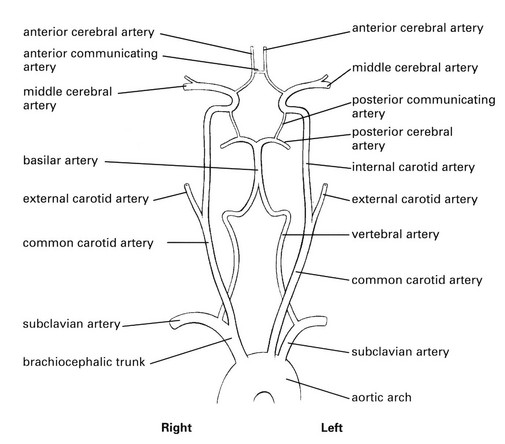

Blood supply

The main blood supply to the cervical spine and related structures is from the vertebral arteries which originate from the subclavian arteries and finally join to form the basilar artery. During their course they give off branches to the spine and to the spinal cord (anterior and posterior spinal arteries).

The vertebrobasilar system is a ‘closed’ circuit (Fig. 30), starting below in the subclavian arteries and ending above in the arterial circle of Willis. The vertebral arteries run parallel on both sides of the spinal column through the canal formed by the successive transverse foramina, and are the main blood supply for the cervical spine, the spinal cord and the brainstem. Between the axis and atlas the arteries curve backwards and outwards and run over the posterior arch of the atlas. They curve upwards again and run cranially.

Inside the skull they join to form the basilar artery which then splits into a left and right posterior cerebral artery. These arteries communicate with the internal carotid artery from which the anterior cerebral arteries branch off. For a detailed description see online chapter Headache and vertigo of cervical origin.

Uncoarterioradicular junction

There is a close connection between the uncovertebral joint, the vertebral artery and the nerve root. The artery is between the uncinate process and the nerve root. The latter lies behind the artery and just anterior to the facet joint. Degenerative changes leading to osseous, cartilaginous or capsular hypertrophy may result in compression of artery or nerve root. The uncovertebral joint is the main threat to the vertebral artery, the facet joint to the nerve root. Movements such as rotation, combined with either extension or flexion, also influence these structures (Fig. 31).