1 ANATOMY OF JOINTS, GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, AND PRINCIPLES OF JOINT EXAMINATION

Applied Anatomy

TYPES OF JOINTS

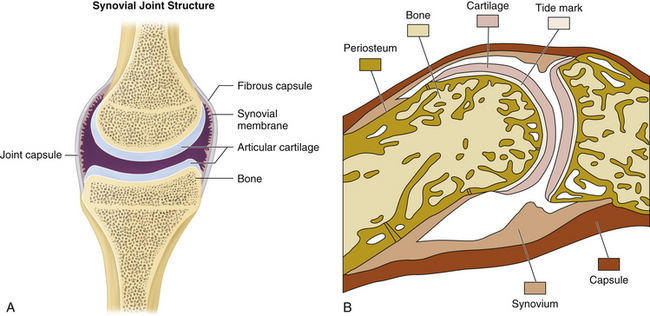

Synovial joints or diarthroses are freely movable joints. The bony surfaces are coated with hyaline cartilage and united by a fibrous articular capsule. The synovial membrane lines the inner surface of the capsule but does not cover the articular cartilage (Figure 1-1). The capsule is strengthened by collateral ligaments. Synovial joints comprise most of the joints of the extremities and are the most accessible joints to direct inspection and palpation. Synovial joints share important structural components: subchondral bone, hyaline cartilage, a joint cavity, synovial lining, articular capsule, and supporting ligaments.

FIGURE 1-1 A, Structure of the synovial joint. B, An example of a synovial joint in sagittal section.

STRUCTURE OF SYNOVIAL JOINTS AND SUPPORTING TISSUES

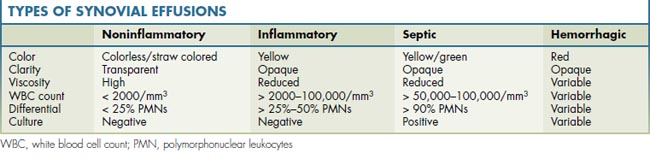

The synovial membrane provides an unobtrusive, flexible, low-friction, well-lubricated lining for diarthrodial joints, tendon sheaths, and bursae. Histologically the synovium consists of two layers: an intimal or synovial lining cell layer—made up of one to three layers of cells or synoviocytes—and a subintimal or subsynovial layer of loose, vascular, fibro-fatty connective tissue. Synovium has important phagocytic functions and produces synovial fluid. Table 1-1 shows different types of synovial effusions.

Joint capsules, ligaments, and tendons are dense fibrous tissues with a major role in musculoskeletal function. Collectively they allow and guide joint motion while resisting high tensile loads without deformation. Laxity or adaptive shortening of these structures affects joint motion and may lead to injury (see Figure 1-1).

Joint capsules attach around articular surfaces to form a continuous envelope for the joint. Capsular cells are predominantly fibroblasts with a dense fibrous matrix surrounding them. The capsule is lined with synovium that provides lubrication for the joint. Ligaments attach bone to bone and function to stabilize adjacent bones by restricting abnormal movements. Ligaments may be intracapsular, capsular, or extracapsular, and they share similar cell and matrix characteristics with the joint capsule and tendon tissues.

General Considerations and History

CATEGORIES OF MUSCULOSKELETAL PROBLEMS

Musculoskeletal problems and rheumatic diseases can be practically classified into five major categories, defined by the tissues predominantly affected: periarticular, articular, bone, nerve, and extraarticular.

At each point in your evaluation—as you gather essential historical, physical, and selected laboratory information—ask what tissues are primarily affected. Thinking of musculoskeletal problems in this way provides a useful framework for organizing clinical information. Recognizing the pattern of predominant tissue involvement then directs your attention toward well-defined members of each category, helping to organize your differential diagnosis (Table 1-2).

TABLE 1-2 MUSCULOSKELETAL PROBLEMS AND RHEUMATIC DISEASES, AFFECTED TISSUES, AND PATTERNS OF INVOLVEMENT

| Periarticular (Soft-Tissue Problems) |

| Bursitis, tendinitis |

| Capsular, ligamentous sprain |

| Muscular strain |

| Articular (Synovial and Cartilaginous Joints) |

| Osteoarthritis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Spondyloarthritis |

| Crystalline arthritis |

| Infectious arthritis |

| Bone |

| Trauma |

| Osteoporosis |

| Avascular necrosis |

| Infection |

| Tumor |

| Nerve |

| Radiculopathy |

| Entrapment |

| Neuroarthropathy |

| Complex regional pain syndromesFibromyalgia (generalized musculoskeletal pain) |

| Extraarticular (Systemic Connective Tissue Diseases) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Antiphospholipid (anticardiolipin) antibody syndrome |

| Sjögren syndrome |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica |

| Systemic vasculitis |

| Inflammatory myopathy |

| Sclerodermatous diseases (skin and fascia) |

CHARACTERISTICS OF MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN

Patterns of Involvement

For instance, in the shoulder girdle, supraspinatus function is necessary to produce normal rotation of the humeral head on the glenoid fossa during abduction. Supraspinatus weakness results in substitution by the deltoid, a large muscle much farther away from the center of rotation of the humeral head. Preferential use of the deltoid muscle in abduction results in superior gliding of the humeral head, producing an impingement syndrome with tendinitis, bursitis, rotator cuff tears, and arthritis.

Physical Examination

ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS

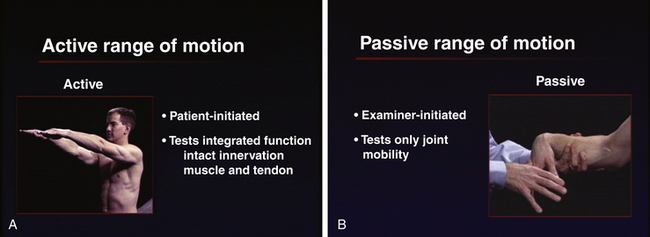

Both active and passive ranges of motion are important in assessing joint function. Active range of motion is patient-initiated movement of the joint that tests integrated function and requires intact innervation, muscle and tendon function, and joint mobility. Passive range of motion is examiner-initiated movement of a joint and tests only joint mobility. The combined use of passive as well as active range of motion minimizes the need for patient instruction and maximizes the speed and efficiency of the exam (Figure 1-2). Whenever joint movement is anticipated to be painful, it is best to first observe active range of motion (patient-initiated movement) to appreciate the degree of pain and dysfunction before gently attempting passive range of motion (examiner-initiated manipulation).

Importance of Objective Findings

Joint swelling is an extremely important and definitive clinical sign. Swelling due to synovial fluid (joint effusion) or swollen synovial tissue (synovial membrane inflammation = synovitis) provides the clinician with definitive evidence of the presence of arthritis. Swelling due to bony enlargement (osteophytes) is also an extremely important physical finding, indicating the presence of underlying primary or secondary osteoarthritis.

EXAMINATION COMPONENTS

Recording Exam Findings

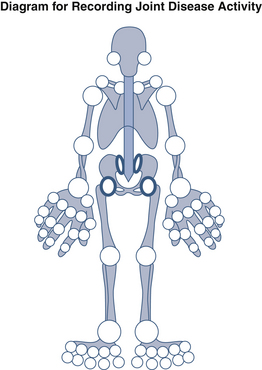

Use of cartoon diagrams to record findings can also be quite helpful (Figure 1-3).

Agur A.A., Dalley A.F. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, eleventh ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

Grant J.C.B. Grant’s Method of Anatomy: A Clinical Problem-Solving Approach, eleventh ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1989.

Griffin L.Y., editor. Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care, third ed, Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 2005.

Hoppenfeld S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1976.

Kendall F.P. Muscle Testing and Function, fifth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Klippel J.H., editor. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, thirteenth ed, Atlanta, GA: Springer-Arthritis Foundation, 2008.

Sahrmann S.A. Movement Impairment Syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.

Weinstein S.L., Buckwalter J.A. Turek’s Orthopedics, sixth ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2005.