9 THE TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT

Applied Anatomy

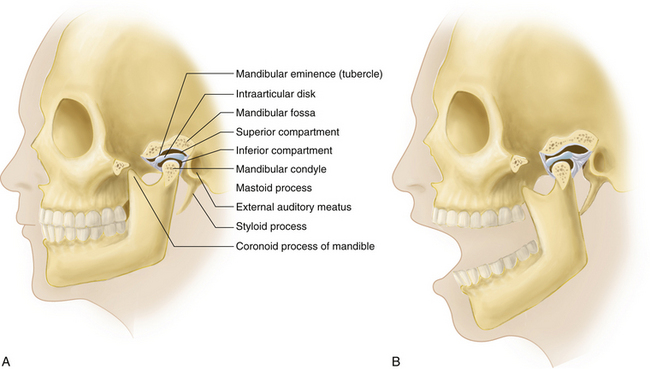

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is an articulation between the mandibular condyle and both the mandibular (glenoid) fossa and the articular eminence (tubercle) of the temporal bone (Figure 9-1). The paired TMJs are classified as condylar joints, because the mandible articulates with the skull by means of two distinct articular surfaces, or condyles. Unlike other synovial (diarthrodial) articulations, the articulating surfaces of the TMJ are covered by fibrocartilage in place of hyaline cartilage. An intraarticular fibrocartilaginous disk (meniscus) divides the joint into a large superior and a smaller inferior compartment, each lined with synovial membrane (see Figure 9-1). The disk consists of a thin, central portion; a thick, large, highly innervated and more vascular posterior portion (posterior band); and a smaller anterior portion (anterior band). The disk is tightly bound to the medial and lateral poles of the mandibular condyle. It provides congruent contours, acts as a shock absorber during mastication, and stabilizes the joint during mandibular movements. The stability of the TMJ depends on the osseous, conformation, muscles of mastication, capsule, ligaments, and intraarticular disk. The capsule is thin and loose and allows a wide range of movements. It is attached to the condyle and to the articular eminence, and it is reinforced on the lateral aspect by the lateral temporomandibular ligament and on the medial aspect by the sphenomandibular ligament.

MOVEMENTS

In the closed position, the mandible lies in the glenoid fossa, in contact with the posterior band of the disk (see Figure 9-1). In the resting position, the mouth is slightly open so that the teeth are not in contact. In centric occlusion occurs with maximal contact of the teeth, the position assumed by the jaw when swallowing.

TEETH

In humans, there are 20 deciduous—primary or “baby”—teeth, and 32 secondary, or permanent, teeth. Deciduous teeth are shed between the ages of 6 and 13 years. To identify or label the secondary teeth for the purposes of communication and treatment, their locations are divided into four quadrants: upper left (quadrant 1), upper right (quadrant 2), lower left (quadrant 3), and lower right (quadrant 4). When labeling or identifying deciduous teeth, the quadrants are continued so that deciduous teeth would be found in quadrants 5 through 8, with quadrant 5 being the deciduous “partner” of quadrant 1, used for secondary teeth and so on. In each quadrant, the teeth are numbered from 1 (most medial) to 8 (most distal). Therefore, a mandibular right first molar would be called tooth 4.6, or simply 46, and a first mandibular deciduous molar on the right side would be labeled tooth 8.5, or 85. Loss or restoration of teeth and malocclusion has been considered a major factor in the development of TMJ pain. Although this used to be considered a major risk factor for TMJ dysfunction, unless the occlusal changes are so great as to render the occlusion nonfunctional (e.g., no posterior occlusion at all), it is no longer considered as such (De Boever, 2000).

Temporomandibular Joint Pain and History Taking

Pain reported in the TMJ is a relatively common symptom, but it can have diverse causes. It may originate in the TMJ itself, or it may be referred from the teeth, ear, parotid gland, muscles of mastication, cervical spine, or head (Table 9-1). Important points in the history include site, duration, character, radiation, and provocative factors of TMJ pain. The physician may also inquire about any recent dental work and whether a patient grinds the teeth. Both bruxism—forced clenching and grinding of the teeth, especially during sleep—and habitual nail biting have been associated with a temporomandibular disorder syndrome, which will be discussed later. However, these are basically associations and to date have not been demonstrated to be causal. That said, these characteristics might have an impact on pain severity, timing, and responsiveness to treatment. In fact, apart from TMJ pain syndromes that arise following hyperextension-flexion injury, most of these conditions are idiopathic in nature (Romanelli, 1992; Goldberg, 1996; and Brooke, 1978).

TABLE 9-1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT (TMJ) PAIN

| Arthritis of the TMJ |

| Osteoarthritis (OA) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) |

| Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) |

| Trauma |

| Infection |

| Gout |

| Temporomandibular Disorder Syndrome (TMDS) |

| Internal Derangement due to Meniscal Displacement |

| Condylar Agenesis, Hypoplasia (Retrognathism), and Hyperplasia (Prognathism) |

| Neoplasms of the TMJ (rare) |

| Chondroma |

| Osteochondroma |

| Osteoma |

| Referred TMJ Pain |

| From the parotid salivary gland |

| From the paranasal sinuses |

| From the ear |

| From the teeth |

| From the nasopharynx |

| From the cervical spine |

| Other Causes of Facial Pain |

| Trigeminal neuralgia |

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis |

| Migraine headache |

| Cerebral tumors, tetanus, Parkinsonism |

| Fibromyalgia |

| Psychosomatic TMJ pain |

Locking of the TMJs can be caused by subluxation of the joint or, more likely, may be caused by anterior displacement without reduction of the meniscus (i.e., TMJ disk). Clicking, popping, or snapping of TMJs, often bilateral, occurs when the TMJ disk is positioned anterior to its normal position. However, in contrast to a locked joint, opening movement that requires translation of the TMJs can cause popping or clicking in one or both of these joints that may be audible or at least detected by palpation. This phenomenon occurs because the joint actually snaps back over the displaced disk, leading to the reestablishment of a normal relationship between the condyle and the central zone of the disk (Westesson, 1985). Other causes of clicking and popping can include a meniscal tear, uncoordinated lateral pterygoid muscle action, and osteoarthritis (OA).

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

The TMJs are inspected for pain, swelling, redness, symmetry, clicking, crepitus, abnormal movements such as asymmetric translation, lack of movement, and hypermobility. Effusion of the TMJ manifests as a rounded bulge just anterior to the external auditory meatus. Arthritis of the TMJs, particularly rheumatoid (and not OA), can predispose to the development of an obvious anterior open bite, in which the patient cannot bring his or her anterior teeth together (e.g., to bite off a piece of thread). In children this might also result in the development of a disturbance of bone growth leading to a shortened, recessed lower jaw and excessive overjet. While excessive overjet may result from various causes, be they congenital or acquired, there are no studies revealing a conclusive relationship between factors of occlusion, such as overjet and overbite, with the development of temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) (Gersh et al, 2004). It should also be recognized that other diseases can cause lysis or destruction of one or both TMJs, including neoplasia (benign or malignant), and these must be ruled out in the absence of a history consistent with adult or juvenile rheumatoid disease.

PALPATION

The TMJs can be located by placing the tip of the index finger just anterior to the external auditory meatus and asking the patient to open the mouth about halfway. The lateral poles of the TMJs will then become palpable by the tip of the examiner’s finger. The joint is palpated for warmth, tenderness, synovial thickening, effusion (a fluctuant mass), crepitus, or snapping or clicking with movement. With the patient’s mouth open, the TMJ can be palpated with the little finger placed in the external auditory meatus (fleshy part anteriorly). The patient is then asked to close the mouth when the examiner first feels the condyle touch the finger. With the mouth closed, the TMJs are in the resting position with a freeway space between the anterior teeth (normal range 2 to 4 mm) (Kerr, 1974). By palpating the condyle and noting its location within the mandibular fossa with the patient’s mouth closed, partially open, and wide open, the examiner can determine various degrees of dislocation.

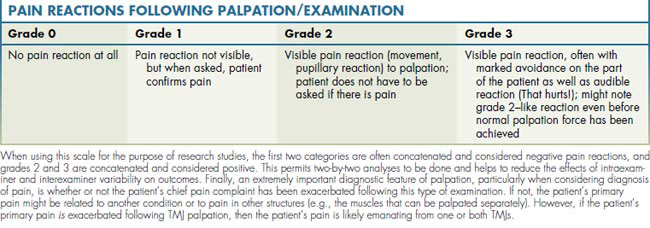

When assessing for pain, one generally tries to maintain a consistent force of palpation. If tissues are clinically tender, it is generally recommended that the force needed to evoke a meaningful pain reaction is that which, when pressing the finger on a tabletop, the fingernail bed will blanch. If the pressure is too light, clinically tender tissues will not be identified; similarly, if too much force is applied, even normal tissues will be perceived as painful. For the purposes of standardization, it is also helpful to grade a patient’s pain reaction following palpation of the TMJs and surrounding musculature. In this case, a discontinuous but relatively reliable scale has been developed, as shown in Table 9-2.

RANGE OF MOVEMENT

As alluded to earlier, jaw opening can be characterized as being assisted or unassisted. Unassisted opening is generally close to assisted opening in extent, when there is no pain or other disease associated with either the TMJs or their associated muscles, and it is measured by having the patient open his or her mouth to its widest extent or to the point where pain interferes with such movement. Assisted opening is measured, with the examiner wearing gloves, by placing the middle finger on the incisal edges of either the maxillary or mandibular teeth and the thumb on the incisal edges of the opposing incisors. The thumb and middle finger are then brought together gently and slowly, in a scissors movement, to determine whether it is possible to assist the mandible to open more than it did with unassisted opening. In these cases, there might be too much pain to even do this. However, in most cases this maneuver can still be done. Presuming no intraarticular disease, such as an anteriorly displaced TMJ meniscus without reduction, and as long as there is no extremely severe pain, the mandible can be coaxed to open, sometimes another 1 to 2 cm. This is also parallel to the concept of a springy feeling at maximal opening and would generally be consistent with a diagnosis of muscular pain and/or muscle trismus that is causing a restriction in unassisted opening. Alternatively, if the mandible can only be coaxed to open another 1 to 5 cm, a so-called hard feeling will be detected. The latter finding often suggests intraarticular disease, such as an anteriorly displaced TMJ disk without reduction. Another condition that could cause this type of finding might be TMJ ankylosis related to trauma or other bone/joint disease, including infection, and it may require surgical intervention (Straith, 1948). Conditions associated with TMJ disk position and shape will be discussed in more detail later (see Temporomandibular Joint Pain and History Taking).

MUSCLE TESTING AND NEUROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Although there is no question that patients will present with jaw-associated pain because of TMJ disease, it must also be recognized that pain in the surrounding muscles can also cause pain; in most instances, this is in fact the case (Dworkin, 1990). Moreover, most patients present with both muscular and TMJ pain. In cases of combined joint and muscle pain, the overall symptom profile and responses to treatment suggest that it is the muscular pain that is of paramount importance as opposed to pain strictly in the TMJ (Hapak, 1994). Therefore in addition to assessment of the TMJ itself, it is critically important to also test for muscle pain. Furthermore, orofacial pain can arise as a consequence of dentoalveolar disease or neuropathy, which underscores the importance of carrying out an appropriate neurological assessment as well.

When testing for pain in the muscles of mastication, it is important to examine the external muscles—masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid at the angle of the mandible, and sternocleidomastoid—by palpation. The internal muscles must also be palpated; these include the masseter at its zygomatic attachment and the coronoid attachment of the temporalis. One can also palpate the medial pterygoid muscles, but this can also induce gagging, which makes it difficult to assess for pain reactions. The lateral pterygoid muscles are also palpated, but in reality, it is doubtful that they can actually be reached during a physical examination. The same amount of digital pressure on the muscles of mastication as described for palpation of the TMJs should be used. Similarly, the patient’s pain reactions can be gauged using the measurement system described in Table 9-2. Equally as important, as discussed with respect to examination of the TMJs, a patient might or might not feel pain following palpation; if the patient does feel pain, and the patient’s chief pain complaint has been exacerbated following palpation of the muscles of mastication, it can be concluded that the principal source of pain is muscular. That said, patients suffering from chronic muscle pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia, which is a common comorbid condition for patients with TMJ or associated pain in the muscles of mastication (Dao, 1997), might report severe pain following palpation; but their chief pain complaints might not be exacerbated. This latter type of finding should suggest a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, which would need further medical assessment, such as examination by a rheumatologist, neurologist, or physiatrist—three appropriate medical subspecialties concerned with these conditions.

Common Musculoskeletal Disorders of the TMJ

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR ARTHRITIS

Temporomandibular (TM) arthritis can be caused by trauma, infection, OA, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), juvenile idiopathic (rheumatoid) arthritis (JIA), or crystal-induced arthritis—such as gout, and even pseudogout—or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition arthropathy (Pritzker, 1994). In some rare cases, TM arthritis may be caused by malignant metastatic or primary disease. The pain of TM arthritis may radiate to the teeth, face, or ear, and it is made worse by jaw movements during eating, chewing, and speaking. With regard to OA, pain usually occurs once there is loss of the fibrous articular joint surface. As a result, the loss of this protective layer exposes the innervated and vascularized osseous tissue to the effects of movement and forces that result in pain (Okeson, 2005). Rheumatoid arthritides (including JIA) occur as a result of proliferation of inflamed synovial membranes onto the articular surfaces (Okeson, 2005). Other symptoms include stiffness, restriction of movement with inability to fully open the mouth, swelling, clicking, and sometimes locking. Local tenderness, swelling, synovial thickening, effusion, fine or coarse crepitus, and sometimes a palpable click are the main findings. In chronic arthritis, excessive play of the TMJ is common.

INTERNAL DERANGEMENTS

Clinically, there is a painless incoordination phase initially, during which the patient experiences a momentary catching sensation on mouth opening. This is followed by the clicking and popping associated with anterior disk displacement and reduction into the normal position with mouth opening. Some patients may subsequently develop restricted jaw movements with intermittent or permanent locking caused by anterior disk displacement without reduction on attempted mouth opening. The common factor here is that in such cases, almost all patients would have reported prior TMJ noises with jaw opening and/or closing (a reciprocal click) prior to the development of closed lock. Furthermore, on development of a closed lock caused by anterior displacement without reduction, the patient will also report that the clicking is no longer present. The diagnosis of internal derangement can be confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); but in fact, history and clinical examination are just as sensitive (Romanelli et al, 1993).

Management

Although abnormal TMJ signs, mostly joint noises or clicking, are relatively common, symptoms are less frequent, and only a minority of patients seek medical advice for them. Treatment of painless TMJ clicking is not recommended, unless the condition is seriously bothering the patient. If the clicking is painful, treatment is indicated and can include treatment with an intraoral appliance known as a biteplane. Some clinicians advocate for a biteplane that positions the mandible anteriorly so as to “recapture” the disk (Gelb, 1979). In some cases arthroscopic surgery is performed, also to recapture and/or repair the disk, and this might be aided by viscosupplementation, placement of hyaluronate into the TMJ capsule following arthroscopic surgery. Alternatively, a procedure called arthrocentesis has also been shown to be effective in either reducing the symptoms of clicking or at least reducing the associated pain. In fact, arthrocentesis is a component of arthroscopic surgery, which will be discussed in more detail later, and could actually be the most important part of the treatment that leads to improvement (Tenenbaum, 1999). The goals of arthrocentesis are not to recapture or repair the joint but to lavage inflammatory byproducts out of the joint capsule and to then replace the joint fluid with hyaluronate and/or a corticosteroid. Interestingly, most evidence suggests that in spite of treatment, displaced TMJ menisci are not recaptured and do not return to a normal position—and yet patients still report clinically significant improvement in their pain symptoms, if not the clicking (Nitzan, 1991 and Freeman, 1997). Another useful, noninvasive treatment modality is physiotherapy that involves manipulation, massage, moist heat, and jaw exercises (Rocabado, 1982).

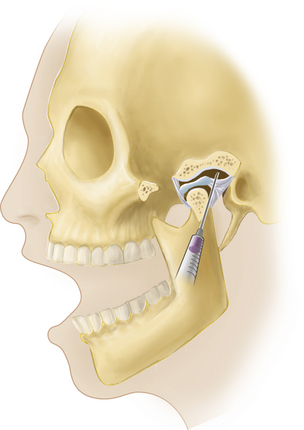

LOCAL ASPIRATION AND INJECTION/ARTHROSCOPIC TREATMENTS

When considering treatment of an inflamed TMJ, local aspiration and injection of the joint may be required, with a steroid and/or with hyaluronate. With the patient sitting or reclining and the head supported, the joint line is palpated as a depression located 1 to 2 cm anterior to the tragus, and the mandibular condyle is felt as it moves during mouth opening and closing. With the patient’s mouth open, a 27 gauge needle is inserted into the joint perpendicular to the skin and directed slightly posteriorly, medially, and superiorly, with care being taken not to inject directly into the intraarticular disk (Figure 9-2). The ease of injection and/or aspiration of fluid is the best guide to ensure that the needle’s point is within the joint cavity. Generally speaking, local anesthesia should be established as per routine when carrying out such procedures. More recent developments in this approach, and with arthrocentesis in particular, require a similar approach but also involve the development of a draining channel with a second needle. This allows for inflammatory cytokines (e.g., prostaglandins) to be flushed from the joint capsule, followed by placement of the steroid and/or hyaluronate. It should be noted that if a patient’s pain is not alleviated following local anesthetic administration into the joint, presuming the patient is in pain at the time of presentation, the patient’s pain is likely not emanating from the joint. This would mean that another source of pain should be considered; as alluded to earlier, this is likely to be muscular, presuming other sources of pain, such as dentoalveolar pain and otitis media, have been eliminated diagnostically. Therefore, injection of the TMJ is not only a possible therapeutic measure, it can be used for diagnostic purposes as well.

Arthroscopic methods can be used to guide aspiration and injection along with surgical management of intraarticular disease. Interestingly, studies focused on the use of arthroscopic surgery have shown that surgical outcomes can be affected by the presence and/or severity of a psychopathological disorder (Freeman, 1997; Dworkin, 1994; and Murray, 1996). The various investigations have demonstrated that the biomechanical aspects of jaw function—as measured directly and objectively, as with maximal mandibular opening (MMO)—were unaltered following arthroscopic surgery. In parallel, the incidence and severity of TMJ sounds did not change following surgical treatment. However, there were marked reductions in pain (> 60%). Moreover, although there were no changes in the objective measurements of either MMO or joint noises, based on measurements made with visual analog scales, patients perceived at least 60% reductions in joint noises that also correlated with similar perceptions in their maximal jaw opening. These data suggest that although biomechanical function might be an important parameter insofar as joint function is concerned, pain might be the overriding symptom; when pain is reduced, patients seem to perceive that their biomechanical problems (i.e., maximal jaw opening) have improved to a similar extent.

INJECTION OF MUSCLES OF MASTICATION

When it is suspected that a patient’s symptoms are related to painful muscles of mastication, diagnostic, and in some cases therapeutic, injection of local anesthetics may be considered with or without a corticosteroid. As suggested for injection of the TMJ, the administration of a local anesthetic prior to placement of a steroid, if a steroid is to be used, should also lead to elimination or at least reduction in the patient’s chief pain complaints. These injections can be therapeutic (Wheeler, 2004) or at least diagnostic. Both internal and external muscles of mastication can be injected, depending on what muscles were shown to be tender to palpation; in general it is suggested that when the muscles are injected with a local anesthetic, it should be done without a vasoconstrictor. Dry needling has also been used, but its effectiveness is questionable (Furlan et al, 2003).

PREDICTION OF TREATMENT OUTCOMES FOR TMD AND ASSOCIATED MUSCULOLIGAMENTOUS PAIN CONDITIONS

Predicting treatment outcome in chronic pain cases, and with temporomandibular disorders in particular, is one of the most challenging aspects of managing these conditions. Unlike more conventional medical and dental models, in which the response to treatment is based on a number of well-defined interventions, chronic pain management provides numerous challenges not observed in other conditions. The biopsychosocial model used to explain the etiology of chronic pain may provide some insight into the variability of patient outcomes. Additionally, the originating trigger to the complaint, such as a motor vehicle accident, and other cofactors, including sleep disturbance and fibromyalgia, have been shown to play a significant role in determining the outcome of therapy.

In general, patients presenting with idiopathic TMD (iTMD)—those conditions not associated with a traumatic origin—recover in approximately 75% to 80% of cases (Brooke, 1977). Contrary to this observation, those patients presenting with signs and symptoms associated with a temporomandibular disorder with an onset in conjunction with a motor vehicle accident (pTMD) tend to do poorly in treatment and require more modalities of therapy than those patients that do improve. In fact, only about 48% of post-traumatic temporomandibular disorder sufferers suggest that they improved following conservative therapy (Romanelli, 1992). It has been suggested that those suffering from signs and symptoms associated with pTMD demonstrate a greater incidence of sleep disturbance, decreased energy level, mood swings, problems with cognitive functioning, and memory and concentration disturbances. These characteristics are similar to those seen in patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Afari, 2008). Yet in most TMD populations, there is no overt neurological deficit identified. Thus, it has been suggested that further characterization of these conditions, in particular those temporomandibular disorders that are more refractory to treatment, via the use of neuropsychological testing similar to that used in the post-traumatic TMD group may be helpful in not only assessing common features but may assist in formulating a more accurate diagnosis early in therapy.

A number of neuropsychological tests are available for assessment of cognitive functioning. However, some of the more common tests include a simple and complex reaction-time test, the California Verbal Learning Test, the Peterson-Peterson Consonant Trigram Test, and the Symptom Checklist-90 revised (SCL 90R). It has been suggested that individuals who have suffered from a head injury may develop difficulties with information processing. Therefore, the reaction-time tests and memory tests that assess the ability to encode information, including short and long-term memory function, may all be reflective of a cognitive deficit despite a normal neurological examination. It has been demonstrated by Goldberg et al (1996). that patients presenting with TMD symptoms associated with a motor vehicle accident did worse on reaction time and cognitive function tests compared to those suffering from a TMD of an idiopathic origin.

Following up on this work, it was suggested that neuropsychological deficits may play an integral role in mediating poor treatment outcomes in TMD patients. Accordingly, using various neuropsychological testing tools, as was done in the pTMD population, may provide some form of predictor in terms of poor treatment outcomes in the iTMD population. Although reaction-time testing was shown to be a poor predictor of treatment outcomes, other neuropsychological parameters described in the California Verbal Learning Test and the Peterson-Peterson Consonant Trigram Test were able to discriminate between responders and nonresponders in an iTMD population (Grossi, 2001). Conceivably, these tests might be utilized to predict poor outcomes and thereby funnel patients into therapies to improve memory and cognition, which may in turn improve outcomes overall. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that these findings may be extrapolated to other chronic pain conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, with consistent findings noted (Grossi, 2008).

One of the overriding factors associated with chronic pain, and with TMD in particular, is the presence of a sleep disturbance. Chronic diffuse myalgia, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome are just some of the conditions associated with chronic sleep disturbance (Moldofsky, 1993). Along with that, it has been demonstrated that post-traumatic TMD patients are more likely to claim to suffer from a sleep disturbance and other symptoms related to affect than a comparative nontraumatic TMD population (60% vs. 14%) (Romanelli, 1992). However, in those that are considered refractory to treatment, it was demonstrated that on average, the nonresponding TMD population performed worse on most cognitive tests than those TMD patients who responded to treatment. Additionally, results of the University of Toronto Sleep Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) indicated that elements of a sleep disturbance may have been present in the nonresponsive TMD group, although the diagnosis of a sleep disturbance could not be definitively made (Grossi, 2001). Overall, however, studies on TMD and sleep disturbance are limited. It has been reported that as many as 77% of those suffering from orofacial pain suffer from a sleep disturbance (Riley, 2001). The sleep–pain relationship is complicated by mood (Menefee et al, 2000), with poor sleepers endorsing higher scores on measures of depression and anxiety (Haythornthwaite, 1991). In a sample of patients with orofacial pain, sleep quality was predicted by depressed mood or psychological distress and greater pain severity and less perceived life control (Yatani et al, 2002). However, in a study assessing psychological and cognitive variables that may be predictive of positive outcomes in TMD patients undergoing physiotherapy treatment, it was determined that neuropsychological test results, as well as sleep quality, were not able to predict treatment outcome in any meaningful way (Bielawski, 2008). Although many factors may contribute to the etiology and pathogenesis of TMDs, it is still beyond our ability to accurately predict those who will or will not respond to therapy, no matter which modality is utilized.

Conclusions

Clearly, factors that affect chronic pain in other joints and associated musculature within the body play an equally important role with regard to problems surrounding the TMJ and the muscles of mastication. What makes this structural complex so different is that pain in and around the TMJ and its muscles can arise from several sources, ranging from dentoalveolar to muscular origins. Moreover, it is also clear from findings now reported in the literature, and as described in this final section, that higher-center control of pain and suffering (i.e., the central nervous system) plays an extremely important role in relation to chronicity of pain regardless of the anatomical location of the pain. Mounting data suggest that apart from clearly biomechanical problems associated with joint movements, and indeed even when biomechanical problems seem to explain any one patient’s symptoms, manipulation of pain perception, possibly with the use of treatment approaches that rely more heavily on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Flor, 1993), might prove to be as useful, if not more so, in management of joint-associated pain than some surgical or more invasive treatment methods currently in use.

Afari N., Wen Y., Buchwald D. Are post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and temporomandibular pain associated? Findings from a community-based twin registry. J. Orofacial Pain. 2008;22(1):41-49.

Bielawski D.M. Treatment Response to Physical Therapy in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto; 2008.

Brooke R.I., Stenn P.G. Postinjury myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome: Its etiology and prognosis. Oral Surg. 1978;45:846-850.

Brooke R.I., Stenn P.G., Mothersill K.J. The diagnosis and conservative treatment of myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1977;44(6):844-852.

Dao T.T., Reynolds W.J., Tenenbaum H.C. Comorbidity between myofascial pain of the masticatory muscles and fibromyalgia. J. Orofacial Pain. 1997;11(3):232-241.

De Boever J.A., Carlsson G.E., Klineberg I.J. Need for occlusal therapy and prosthodontic treatment in the management of temporomandibular disorders. Part II: tooth loss and prosthodontic treatment. J. Oral Rehab. 2000;27(8):647-659.

Dworkin S.F., Huggins K.H., LeResch L. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: Clinical signs in cases and controls. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1990;120:273-281.

Dworkin S.F., Massoth D.L. Temporomandibular Disorders And Chronic Pain: Disease Or Illness? J. Prosthetic Dentistry. 1994;72:29-38.

Flor H., Birbaumer N. Comparison of the Efficacy of Electromyographic Biofeedback, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, and Conservative Medical Interventions in the Treatment of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993;61(4):653-658.

Freeman B.V. The Effect of Psychopathological Disorders on the Outcome of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopic Surgery: A Comparison of Objective and Subjective Outcome Measures. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto; 1997. p. 52

Furlan A.D., van Tulder M.W., Cherkin D. Acupuncture and dry needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2003.

Gelb H. An orthopedic approach to occlusal imbalance and temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Dental Clin. Nor. Am. 1979;23(2):181-197.

Gersh D., Bernhardt O., et al. Angle Orthodontist. 2004;74(4):512-520.

Goldberg M.B., Mock D., Ichise M. Neuropsychologic Deficits and Clinical Features of Posttraumatic Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Orofacial Pain. 1996;10:126-140.

Grossi M.L., Goldberg M.B., Locker D., Tenenbaum H.C. Reduced Neuropsychologic Measures as Predictors of Treatment Outcome in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Orofacial Pain. 2001;15:329-339.

Grossi M.L., Goldberg M.B., Locker D., Tenenbaum H.C. Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients Versus Responding and nonresponding Temporomandibular Disorder Patients: A Neuropsychologic Profile Comparative Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2008;21:201-209.

Hapak L., Gordon A., Locker D. Differentiation between musculoligamentous, dentoalveolar, and neurologically based craniofacial pain with a diagnostic questionnaire. J. Orofacial Pain. 1994;8(4):357-368.

Haythornthwaite J.A., Sieber W.J., Kerns R.D. Depression and the chronic pain experience. Pain. 1991;46:177-184.

Kerr, D.A., Ahs, M.M., Millard, H.D., 1974. Oral Diagnosis, fourth ed. Mosby, St. Louis.

Menefee L.A., Frank E.D., Doghramji K. Self-reported Sleep Quality and Quality of Life for Individuals with Chronic Pain Conditions. Clin. J Pain. 2000;16(4):290-297.

Moldofsky H. Fibromyalgia, sleep disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome. Ciba Found. Symp. 1993;173:262-271.

Murray H., Locker D., Mock D., Tenenbaum H.C. Pain And The Quality Of Life In Patients Referred To A Craniofacial Pain Unit. J. Orofacial Pain. 1996;10:316-323.

Nitzan D.W., Dolwick M.F., Martinez A. Temporomandibular Joint Arthrocentesis: A Simplified Treatment for Severe, Limited Mouth Opening. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991;49(11):1163-1167.

Okeson, J.P. (Ed.), 2005. Bell’s Orofacial Pains: the Clinical Management of Orofacial Pain. In Quintessence, sixth ed, p. 329, 353.

Pritzker K.P. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition and other crystal deposition diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheum. 1994;6(4):442-447.

Riley J.L., Benson M.B., Gremillion H.A. Sleep disturbance in orofacial pain patients: pain-related or emotional distress? Cranio. 2001;19(2):106-113.

Rocabado M., Johnston B.E.Jr., Blakney M.G. Physical Therapy and Dentistry: An Overview. J. Craniomandibular Pract. 1982;1(1):46-49.

Romanelli. G.G., Harper R., Mock D., et al. Evaluation. of temporomandibular joint internal derangement. J. Orofac. Pain. 7, 254, 1993.

Romanelli G.G., Mock D., Tenenbaum H.C. Characteristics and response to treatment of posttraumatic temporomandibular disorder: A retrospective study. Clin. J. Pain. 1992;8:6-17.

Straith C.L., Lewis J.R. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1948;3:464-466.

Tenenbaum H.C., Freeman B.V., Psutka D.J., Baker G.I. Temporomandibular disorders: disk displacements. J. Orofacial Pain. 1999;13:85-90.

Westesson P.L., Bronstein S.L., Liedberg J. Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: morphologic description with correlation to joint function. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Path. 1985;59(4):323-331.

Wheeler A.H. Myofascial pain disorders: theory to therapy. Drugs. 2004;64(1):45-62.

Yatani H., Studts J., Cordova M. Comparison of Sleep Quality and Clinical and Psychologic Characteristics in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Orofacial Pain. 2002;16(3):221-228.