Chapter 1 Anatomy

INTRODUCTION

A working knowledge of anatomy is essential to perform any of the myriad procedures associated with cutaneous oncology or esthetic correction of the aging face. Without an in depth working understanding of the pertinent anatomy, there is a real potential for the surgeon to cause damage by cutting into a vital structure or to be so insecure as to not progress very far in one’s acquisition of sophisticated surgical skills.

SURFACE LANDMARKS AND SURFACE ANATOMY

Masseter Muscle and Mid-Pupillary Line

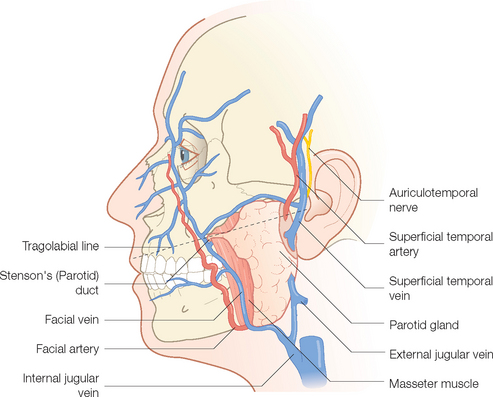

The masseter muscle is a good starting point. It is the large muscle of mastication that occupies the lateral portion of the cheek below the zygomatic arch (Figure 1.1). The parotid gland rests on this muscle. At its anterior border on a line drawn from the tragus to the middle of the upper cutaneous lip, the parotid duct can be identified as it dips inward piercing the buccinator muscle to open into the mouth at the level of the second upper molar. Also, at the jaw line, just at the anterior border of the lower masseter muscle, the facial artery and vein enter onto the face. Pulsation of the artery is often possible at this location. The superficial temporalis artery pulse can be felt just anterior to the ear at its superior attachment. Just beyond this it splits into superior and parietal branches.

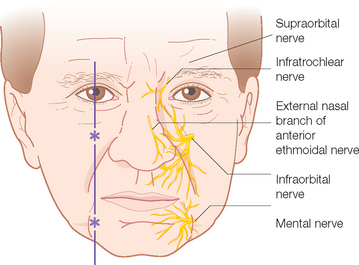

The mid-pupillary line is identified with the patient sitting up and gazing straight ahead. Three important openings in the skull can be located (Figure 1.2). The superior orbital foramen is located at the superior orbital rim. Through it exits the important supraorbital neurovascular complex. Similarly, the infraorbital foramen, about 1 cm below the inferior orbital rim, contains the infraorbital neurovascular artery, vein and sensory nerve. Finally, the mental foramen, located in the alveolar bone of the mandible in the mid-pupillary line, contains the mental artery, vein and nerve. The exact location of all three of these orifices is important when performing respective nerve blocks of the sensory nerves exiting them.

Relaxed Skin Tension Lines (RSTL)

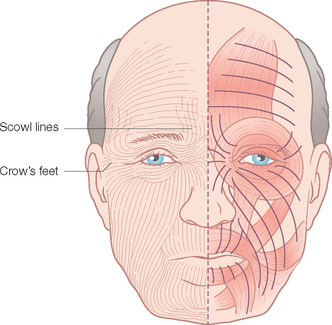

The lines and wrinkles that develop with age and sun exposure become an easily recognizable road map of the face. These wrinkles and creases, first noted as hyperanimation smile lines or frown (scowl) lines, may become permanently etched as elastic tissue degenerates and becomes ineffective in resisting the pull of the underlying muscles of facial expression. These are referred to as the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) (Figure 1.3) and run perpendicular to the exertion of the mimetic muscles below. These lines are often the best choice for the placement of elective scar lines on the face. When they are readily apparent, no problem is posed in designing scar orientation. In younger people, having them animate by grimacing, wrinkling the forehead, smiling or puckering will usually expose the RSTL sufficiently to make the correct choice. Similarly, pinching the skin from various directions will also reveal the flow of the RSTL. Scars not oriented within or parallel to the RSTL are generally more noticeable, as they don’t go with “flow” of the region. This is especially apparent when the patient is smiling or going through some other active form of dynamic emotional expression.

Cosmetic Units and Junction Lines

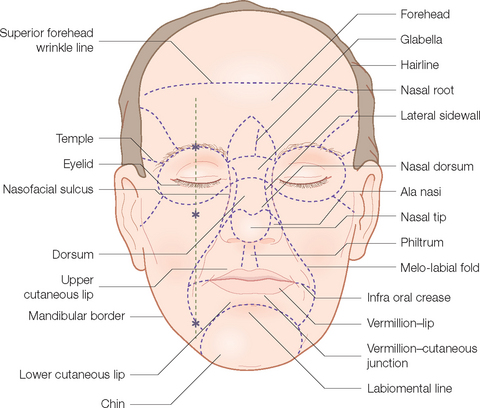

One of the major conceptual advances over the past decade or so in reconstructive and aesthetic surgery is the refinement and widespread acceptance of the junction lines and cosmetic (aesthetic) units of the face (Figure 1.4). Cosmetic unit junction lines are the lines on the face at the borders of the cosmetic units. They include the well-defined melo-labial fold that separates the cheek from the lip, the mental-labial crease that divides the chin from the cutaneous lower lip, the hairline, and the jaw line. More subtle junction lines separate the cheek from the nose (nasofacial) and lower eyelid from the cheek. The nose has several subunits defined by the alar groove, the dorsal crests and the nasofacial line. Collectively, these are the outlines that caricaturists use along with exaggerated features (broad forehead, wide-set eyes, protruding nose) to rapidly define an individual’s countenance and personality. They are also the best location for camouflaging scars. Since lines and shadows are anticipated in these areas, scars tend to visually disappear when placed within them. Conversely, scars crossing junction lines are all too noticeable.

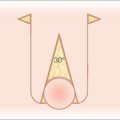

Free Margins: Concept of Tension Vector of Closure

Another important concept when performing facial surgery is that of the free margins; the eyebrows, eyelids, lips and nostril rims. These are important as they offer little resistance to the forces of wound closure and can be easily distorted by excess tension. This can occur from the immediate direct exertion of tension by a side-to-side closure or the delayed application of tension as a second intention healing wound or split thickness graft site contracts. The resulting asymmetries can be both cosmetically unsettling and functionally disabling. Ectropion of the lower lid can lead to permanent visual problems while eclabion and lack of a proper oral seal can cause problems with phonation and eating/drinking while looking unsightly.

The tension vector of closure can be favorably manipulated by one of several techniques:

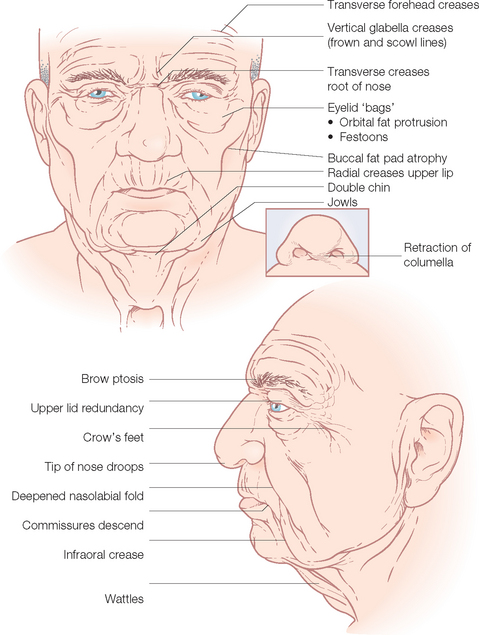

THE AGING FACE

With time, predictable wrinkles and sagging take place (Figure 1.5). This is compounded in some people by changes more related to overexposure to the ultraviolet radiation in sunlight. As noted earlier, youngsters and on into the early thirties, most people do not have wrinkles at rest (Glogau I). The RSTL first appear as hyperanimation lines opposite the pull of the underlying muscles of facial expression (Glogau II). The crow’s feet lines and crinkles under the eyes when smiling are usually the first to become noticeable. With time, the elastic tissue and collagen fascicles that traverse the subcutaneous fat compartment and bind the muscles of facial expression to undersurface of the dermis degenerate and the RSTL become permanently etched on the face (Glogau III). If the patient has significant photo-damage with deposition of solar elastosis within the papillary dermis, the lines become even more prominent, usually with a pronounced roadmap of lines all over the face (Glogau IV).

Along with these events, the incessant pull of gravity and laxity of restraining fascial tissue results in a generalized sagging of the skin that manifests as brow ptosis, dermatochalasis of the upper eyelids, bags under the eyes, vertical lines in the preauricular area, deepened melo-labial folds, rhytids of the lips and pronounced jowls. These areas of redundant and excess, along with the temple and the glabella, constitute the reservoirs of skin available for recruitment for tissue rearrangements.

THE MUSCULOAPONEUROTIC SYSTEM

Introduction

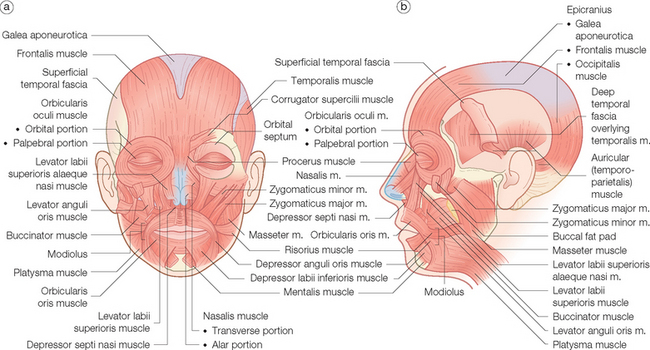

Muscles of facial expression are unique in that they are the only muscles to insert into the skin. They do so via fibrous septae that connect the superior portion of the muscle to the undersurface of the dermis. They also insert or interdigitate with the other mimetic muscles. So while the frontalis muscle wrinkles the forehead and raises the eyebrow, it also helps open the eye widely by partially inserting into the upper fibers of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Figure 1.6).

Muscles Acting around the Nose

The nose is relatively devoid of musculature when compared with the eyes and lips. They consist mainly of the procerus muscle that extends down from the frontalis vertically onto the upper nose across the root and into the aponeurosis of the nasalis muscle on the nasal dorsum. Contraction, usually in concert with the adjacent lip elevators, “scrunches” up and shortens the nose and causes the transverse RSTL across the root. The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi arises from the maxilla under the medial orbicularis oculi and descends vertically to the mid-upper lip, but also sends slips to the lateral ala nasi. In concert with alar fibers of the nasalis muscle, it aids in dilating the nostril with each inspiration. The broad thin nasalis muscle is the intrinsic nasal muscle with alar fibers just discussed, transverse fibers over the dorsum that just tense the skin over the dorsum, and the depressor septi portion that pulls down the septum and aids in deep inspiration.

MOTOR NERVES

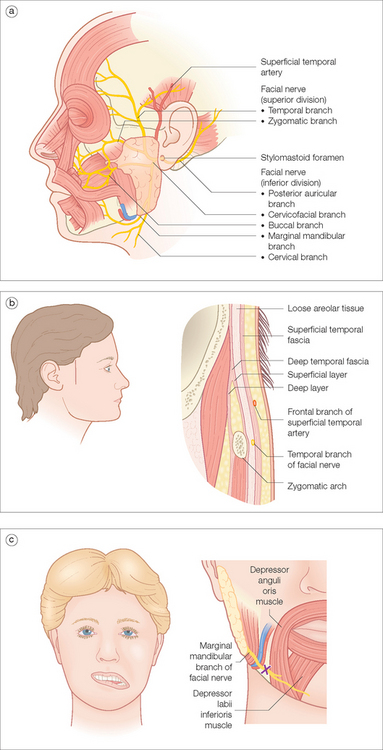

Facial Nerve

After leaving the interior skull at the stylomastoid foramen, the facial nerve classically divides into two major trunks within the substance of the parotid gland, the superior temporofacial and the inferior cervicofacial, which in turn divide into the five major branches: the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches (Figure 1.7a). In reality, the temporal and marginal mandibular branches are single terminal rami in about 85% of the population; the other branches cross-arborize and have multiple rami, making the muscles by these latter nerves less prone to permanent paresis. Obviously, the former are at greater risk for lasting damage if severed or injured during surgery.

Temporal Nerve

The temporal nerve can be roughly projected onto the skin from a line connecting a point 0.5 cm below the tragus of the ear to a point 2 cm above the lateral eyebrow where it innervates the frontalis muscle. Some fibers go to the upper orbicularis muscle. Like the other branches, it is protected in its initial course by the parotid gland through which it runs. It is most vulnerable at the zygomatic arch and the temple where it resides deep in superficial temporal fascia (Figure 1.7b). Remember that the neurovascular bundle containing the sensory auriculotemporal nerve and superficial temporalis artery and vein are more superficial in the lower subcutaneous fat above the superficial temporal fascia. The temporal nerve is most vulnerable during extirpative surgery involving invasive or recurrent skin tumors that frequently occur in this area. Imprecise undermining in the wrong plane may also damage the nerve. It is prudent to recognize that motor nerves, as myelinated nerves, are also subject to the effects of local anesthesia and repeat injections, as may occur in Mohs micrographic surgery, can cause deep, long-lasting nerve blocks. This can cause the unwary surgeon and the patient needless concern for the 10 or more hours it takes nerve function to return. In general, if the surgery has exposed a fascial plane that moves easily in a side-to-side manner to the probing (gloved) finger, it is the superficial temporal fascia and the temporal nerve is probably intact. If the tissue is an immovable, tightly bound-down glistening membrane, the temporal fascia over the temporal muscle of mastication has been reached and the nerve has probably been cut.

Marginal Mandibular and Cervical Nerves

The marginal mandibular nerve, like the temporal branch, is most often a solitary ramus after leaving the parotid gland. It innervates the lip depressors, the risorius muscle, and the mentalis muscles. It is particularly prone to injury because it is relatively superficial and covered by only a variable platysma muscle at the jaw line at the anterior border of the masseter muscle. It may be at, above, or below the jaw line between its exit from the parotid and the anterior border of the masseter muscle. Skin cancers as well as deep acne scars occur frequently in these locations, making surgery dangerous for the unwary. Injury to the nerve results in an inability to retract or depress the corner of the mouth when smiling. The unopposed pull from the unaffected side cause the damaged-side lower lip to flatten and rotate inward upon smiling (Figure 1.7c).

The cervical branch innervates the platysma muscle and is rarely a clinical consideration.

SENSORY NERVES OF THE HEAD AND NECK

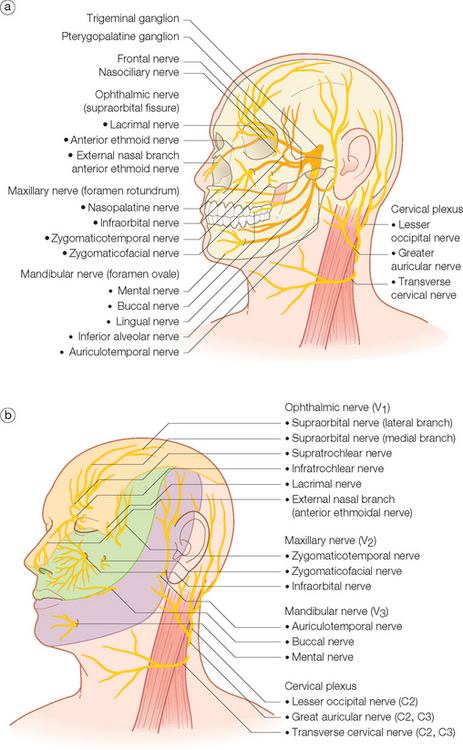

Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial V)

As the nerve of the embryonic first branchial arch, the trigeminal nerve supplies motor fibers to the muscles of mastication, secretory fibers to the lacrimal, parotid, and mucosal glands, and sensory innervation to the face and anterior scalp. It has three main sensory branches originating from the middle cranial fossa-situated trigeminal or gasserian ganglion that divide the face and scalp both horizontally and vertically (see Figures 1.8a and b). These nerve divisions have been classically designated as the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3) nerves.

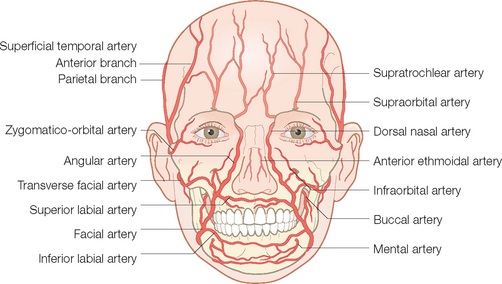

VASCULAR SYSTEM

The incredibly rich blood supply to the face is responsible for the wide array of surgical procedures that can be carried out there. The vascular system to the face is unique in being supplied by two separate artery complexes, the external and the internal carotid systems (Figure 1.9). These systems have rich anastomoses and there is also an extremely rich cross-anastomosis involving paired bilateral arteries such as the superior labial arteries and the supratrochlear arteries. Furthermore, unlike the blood supply on the trunk and extremities where perfusion of the surface is via vertically oriented perforating vessels from the underlying skeletal muscles, the final perfusion of the skin of the face is through the horizontally displaced subdermal plexus that lies high in the subcutaneous fat just under the reticular dermis. This allows for wide undermining of side-to-side closures and the seemingly endless number of random flaps (no named artery in pedicle) that have been designed to repair defects of the face. Proper design of axial pattern flaps (ones that depend on a named artery), such at the mid-line forehead flap, is dependent on knowledge of the location of the major vessels of the face, in this case, the supratrochlear artery.

External Carotid System

The external carotid system is the main blood supply to the lower face, temple and posterior scalp.

The main branch of the external carotid artery to the central face, the facial artery, enters onto the face after exiting the submandibular gland at the anterior border of the masseter muscle at the jaw line (Figure 1.9). It runs obliquely superior within the substance of the lip depressor muscle complex toward the commissure of the lip. Within the substance of the orbicularis oris muscle, it first gives off the inferior labial artery that runs medially through the lower lip to meet its pair from the other side. Next, at the level of the upper lip, the similarly disposed superior labial artery is given off and runs transversely through the upper lip to meet its contralateral partner.

Internal Carotid System

The main volume of blood from the internal carotid system is dedicated to supplying the brain. A portion is allotted to the face, predominantly to the ophthalmic artery whose terminal branches exit the skull as the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries as part of the same-named neurovascular bundles (Figure 1.9). They exit their respective foramen and pierce the overlying frontalis muscle to run superiorly. At this point, they are displaced deep in the subcutaneous fat above the frontalis fascia and subsequently over the galea aponeurotica as they course superiorly over the scalp. They supply the forehead and anterior scalp (see Figure 1.9). As noted earlier, the supratrochlear artery is recruited for the classic and extremely useful axial mid-line forehead flap. Both arteries partake in the rich anastomotic network over the scalp by connecting with branches of the superficial temporalis and occipital arteries. So powerful is this network that traumatic scalping can be repaired by vascular reconnection of even one of these major vessels that supply the scalp.

It is interesting that above the zygomatic arch, the neurovascular bundles containing the major arteries and veins all course in the deep subcutaneous plane above the fascia or muscles of facial expression. Conversely, below the arch, the vessels are usually within the substance of the mimetic muscles and do not course in the company of the major sensory nerves. Knowledge of the route and depth of the vessels will aid in not severing them unintentionally during a procedure in the region. On the other hand, when they have to be cut, as in a lip wedge excision, knowing that the labial artery is located in the very posterior portion of the distal orbicularis oris allows the surgeon to locate and clamp it off immediately before it retracts into the substance of the muscle.

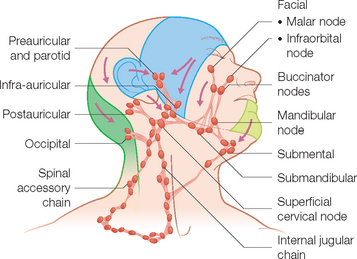

Lymphatic System

Next, afferent drainage is organized in flow patterns that proceed in a superior to inferior, diagonal direction toward the collecting, primary echelon nodes in the upper neck region. These include the submental, submandibular, jugulodigastric, and occipital lymph nodes (Figure 1.10). Drainage from these superficial nodes then proceeds to the deeper cervical systems in the neck (the spinal accessory, internal jugular, and transverse cervical lymph node basins).

SPECIAL STRUCTURES: LIP, NOSE, EYELIDS, EAR

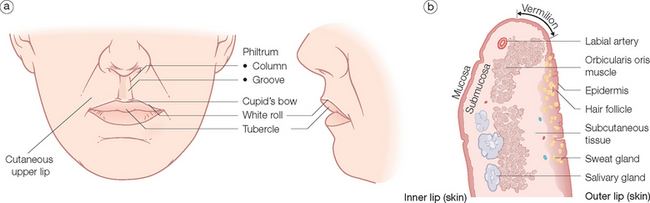

Lip

Internally, they consist solely of the orbicularis oris muscle and the myriad muscular insertions attached to it. They are covered on the outside by skin, on the inside by a wet mucosa and at the vermilion by a dry modified mucosa (Figure 1.11). The submucosa contains many salivary glands on the oral portion.

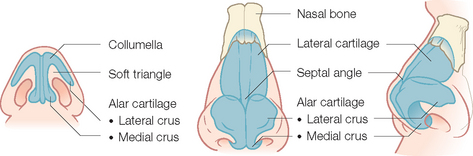

Nose

The nose is an extremely complex, esthetically and functionally important mid-line structure that is all too often the site of an invasive skin cancer. It is supported by a bony/cartilaginous infrastructure that features the inflexible paired nasal bones superiorly and the highly mobile paired upper lateral/alar cartilage complex inferiorly (Figure 1.12). Conversely, the skin over the rigid bony upper portion is highly movable, while the skin over the mobile cartilage portion is thick, sebaceous and bound down.

On the surface, the nose can be broken down into several cosmetic subunits. These include the root of the nose that extends from medial canthus to medial canthus. The skin lines in this concave unit run transversely across it. Obliteration of the concave nature of this area during repairs causes the profile to be dramatically altered and the nose to appear very large on the frontal view. The paired lateral sidewalls separate the nose from the cheek and are in turn separated from each other by the midline dorsum of the nose unit. The heart-shaped convex tip of the nose is the most prominent feature of the nose and is bounded by the paired alae nasi. The columella is the midline structure below the tip separating the nostril apertures and culminating in the upper philtrum of the lip. The RSTL of the upper nose run obliquely out from the medial canthus down the dorsum and lateral sidewall. They end part way down as there are no skin lines on the lower nose. As noted earlier they run transversely across the root.

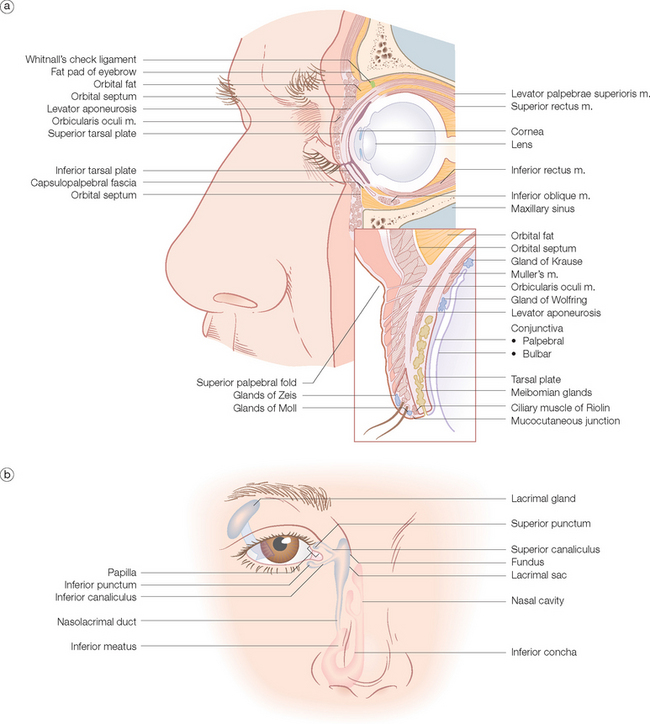

Eyelids

The eyelid is easily the most complicated structure on the face and of extreme functional importance. Successful repair of the unique structures that compose the eyelids are contingent on thorough knowledge of the anatomy as it is so closely related to function. The eyelids guard the globe and orbit and are structured on the orbicularis oculi muscle, whose orbital and palpebral components have been discussed earlier in this chapter. As noted, the orbicularis is responsible for closing the lid. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle and aponeurosis is responsible for opening the eye (Figure 1.13a). It is innervated by the oculomotor or third cranial nerve. It arises from the superior orbit and divides into two components: Muller’s muscle, which attaches into the superior margin of the tarsal plate under sympathetic nerve control, and the levator aponeurosis, which fuses with the orbital septum to form the superior palpebral fold about 10 mm above the lid margin and then continues downward to attach to the anterior surface of the tarsal plate. It also sends fibers through the pretarsal orbicularis to insert into the lid skin. This is why the skin in the pretarsal area is bound down, whereas it is loose and eventually redundant in the preseptal area above the superior palpebral fold. The space between the orbital septum and the levator aponeurosis contains the orbital fat pads. The skin of the eyelids is the thinnest and most elastic in the body. It contains little subcutaneous fat.

The posterior portion of the eyelid closest to the globe contains the tarsal plate that consists of dense fibrous tissue. They give form to the lids and also contain the sebaceous Meibomian glands. The conjunctiva covers the posterior eyelids as well as the globe. Hair follicles of the eyelashes (cilia) with both sebaceous glands (Zeis) and sweat glands (Moll) exit onto the lid margin below the muscular layer while the Meibomian glands exit onto the lid closer to the conjunctival surface.

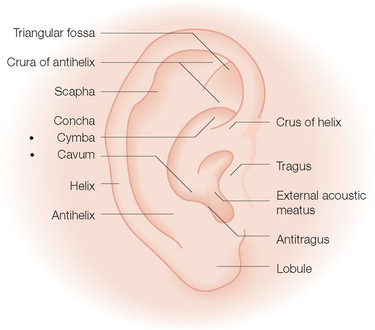

Ear

The outer rim of the ear is the convex helix that extends upward from the lobule to curve around and ending as the crus of the helix that divides the concha bowl into the upper cymba and the lower cavum (Figure 1.14). Opposite the cavum and guarding the external auditory meatus is the small protuberance, the tragus. Also superior to the lobule is the convex antihelix. This structure parallels the helix in its vertical dimension and is separated from it by the depression between them, the scapha. The antihelix splits at its superior end into two crura to form a central concavity, the triangular fossa. Only the lobule is not supported by cartilage.