Chapter 25 Anatomical Double-Bundle Reconstruction of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction remains one of the most common procedures performed by orthopaedic surgeons in the United States, with approximately 100,000 performed per year.1 ACL surgery has evolved tremendously from the original open techniques to modern procedures focusing on endoscopic reconstruction of the anteromedial (AM) bundle using a variety of graft choices and fixation techniques. However, the success of single-bundle ACL reconstruction ranges from 69% to 90%.2,3 In addition, according to Fithian et al,4 95% of patients who underwent single-bundle ACL reconstruction developed medial compartment degenerative radiographic changes after 7 years, and only 47% were able to return to their previous activity level. Because arthrosis was observed medially, it could not be attributed to the initial subluxation event, which usually results in a bone contusion or a concomitant meniscal tear involving the lateral compartment.4

Single-bundle ACL reconstruction is the “gold standard,” but some authors have noted persistent instability with functional testing of single-bundle ACL reconstruction.5,6 Thus, there is a growing trend toward a more anatomical ACL reconstruction that recreates both the AM and the posterolateral (PL) bundles. The double-bundle anatomy of the ACL was first described in 1938 by Palmer et al.7 The terminology of the AM and PL bundles are chosen according to their tibial insertions. The tibial and femoral insertion sites of both the AM and PL bundles have been well described.8,9 The femoral origin has an oval shape, with the center of the AM bundle close to the over-the-top position and the center of the PL bundle close to the anterior and inferior cartilage margin. The femoral origin site changes as the knee is taken through an arc of motion. The two bundles are parallel with a vertical orientation when the knee in extension (i.e., the AM footprint is situated directly superior to the PL footprint). This changes to a more horizontal orientation, with the PL footprint becoming actually anterior to the AM footprint when the knee is flexed beyond 90 degrees. The changing orientation of the two bundles’ footprints as the knee is taken through an arc of motion leads to the observed crossing pattern of the independent components of the ACL. Although the two bundles are intertwined, their functional tensioning pattern is independent throughout the knee’s range of motion.10 Close to extension, the AM is moderately loose and the PL is tight. As the knee is flexed, the femoral attachment of the ACL takes a more horizontal orientation, causing the AM bundle to tighten and the PM bundle to loosen. The ACL has been described as a restraint to anterior tibial displacement and internal tibial rotation. The rotational stabilizing component might be better attributed to the PL bundle.

The idea of reconstructing both bundles of the ACL was described by Mott and Zaricznyj in the 1980s.11,12 They independently described a double-bundle technique. Mott drilled two separate tunnels, whereas Zaricznyj used a single femoral and two tibial tunnels. Despite publishing their results, the technique did not become mainstream. Recent biomechanical evidence supports the anatomical double-bundle ACL reconstruction as more accurately recreating the natural anatomy.13,14 Both translational and coupled rotational translation were significantly less in the specimens with double-bundle ACL reconstruction. We present the senior author’s (F.H.F) technique of anatomical double-bundle ACL reconstruction with two femoral and tibial tunnels using two tibialis anterior allografts.

Preoperative Considerations

History: Signs and Symptoms

ACL injuries occur frequently in sports that involve running, jumping, and cutting movements. They can occur without contact when the foot is anchored to the playing surface—usually by way of cleats or a rubber sole—and the body rotates beyond the tolerance of the ligament as the knee buckles. Thus, it is important to ask the patient how the injury occurred and the position of the knee during the injury, which may also allude to the ACL bundle injury pattern.15 This may be associated with an audible “pop.” Asking whether the athlete was able to continue to play will give you an idea of the severity of the injury. Knee pain and a hemarthrosis are usually present acutely. A complaint of instability is also common, especially with walking downhill or down stairs.

Indications

The absolute indications for double-bundle ACL reconstruction are evolving. Even though single-bundle ACL reconstruction is considered the “gold standard,” the technique can be improved. Gait analysis after single-bundle reconstruction has demonstrated that rotatory instability persists.5 Furthermore, biomechanical cadaveric studies have shown that even lowering the femoral insertion site to the 3- or 9-o’clock position does not fully prevent rotatory instability.16 Clinically, as many as one-fifth of the patients do not resume preinjury activities and usually complain of vague instability symptoms that objectively correspond to a mild persistent pivot shift.17 In comparison, double-bundle ACL reconstruction does restore the rotational component in a cadaveric model.14 It has been suggested that a positive pivot shift after ACL reconstruction is correlated with the development of later osteoarthrosis.18 Perhaps with reconstruction of both the AM and PL bundles, the decreased rotational instability will provide improved overall knee kinematics and may prevent or slow the degenerative changes seen after single-bundle ACL reconstruction.4 A contraindication to performing the double-bundle technique is in the young athlete with open physes. Two tunnels would risk physeal arrest with subsequent malalignment and possible leg length discrepancy.

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia and Positioning

The operative extremity is identified by the patient and initialed by a member of the surgical team. All patients undergo a preoperative femoral nerve block in the holding area by our anesthesia colleagues. The patient is then placed in a supine position and given intravenous conscious sedation. A careful exam under anesthesia is performed and recorded to document the Lachman and pivot-shift maneuvers. Again, the senior author is interested in correlating the exam with the tear pattern of the individual bundles of the ACL. A tourniquet is applied to the proximal thigh. The extremity is then secured within a circumferential leg holder placed at the level of the tourniquet. The foot of the operating table is completely retracted to permit hyperflexion of the knee, which is crucial for later placement of the PL femoral tunnel. The contralateral extremity is placed within a well-leg holder with the hip flexed approximately 90 degrees and abducted and externally rotated away from the surgical field to allow unobstructed access to the operative knee (Fig. 25-1). The leg is elevated for 5 minutes, and the tourniquet is then inflated. The knee is prepped and sterilely draped.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft Preparation

Two tibialis anterior allografts are individually fashioned as a double loop. The folded length of each graft should be approximately 12 cm for sufficient graft tissue. The grafts are trimmed to a folded diameter of 7 mm for the PL bundle and 8 mm for the AM bundle. A #2 braided suture is whipstitched up and down both ends of the graft for 3 cm. The stitch depth is alternated, and care is taken to avoid penetrating the suture and risking weakening or breaking. The graft is then passed through the closed-looped Endobutton (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA). Two Fiberwire sutures (Arthrex, Naples, FL) (one stripped and one nonstripped for later identification) are placed within the button holes. A 2–0 absorbable suture is tied through both strands of the folded graft to secure them once the graft is passed within the closed-looped Endobutton. Each graft is marked to alert the surgeon when to engage or “flip” the Endobutton (Fig. 25-2).

Surgical Landmarks

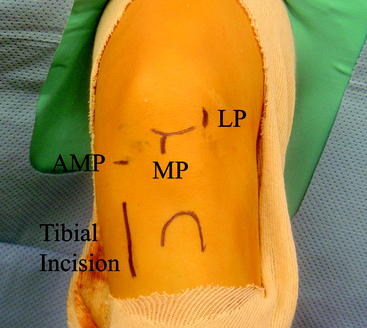

With the knee flexed approximately 45 degrees, the inferior pole of the patella is marked. The inferior extent of the lateral parapatellar portal begins at the level of the inferior pole of the patella and extends proximally for approximately 2 cm. The medial parapatellar portal begins at the level of the inferior pole of the patella and extends distally along the medial aspect of the patellar tendon for approximately 2 cm. The high placement of the portals allows the arthroscopic instruments to enter the knee above the level of the fat pad. The 11 scalpel blade is angled approximately 45 degrees to the skin and distally toward the notch to safely enter the knee without harming the articular cartilage. A low AM accessory portal will be placed with the assistance of a spinal needle to ensure proper trajectory for the PL femoral tunnel (Fig. 25-3). The knee is flexed 90 degrees, and the 11 scalpel blade is angled upward as it enters the skin at the level of the spinal needle marking. The portal is extended proximally approximately 1 cm, avoiding injury to both the underlying meniscus and the articular cartilage.

Specific Steps

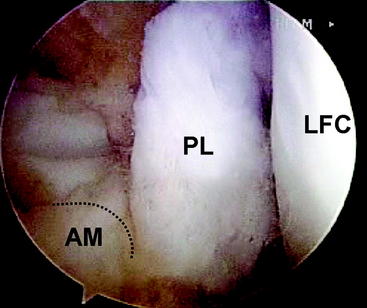

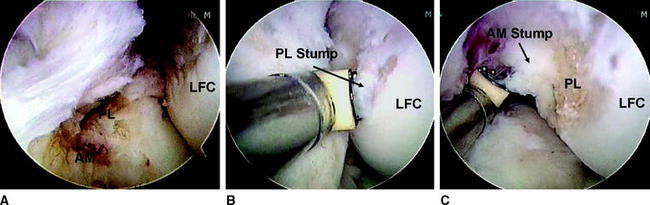

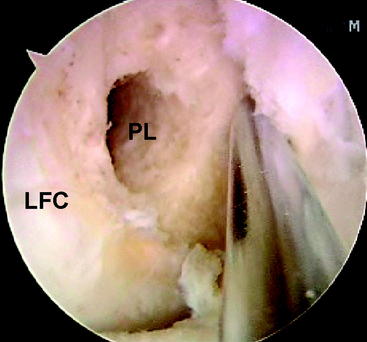

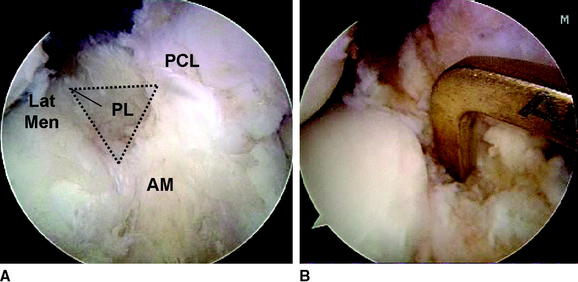

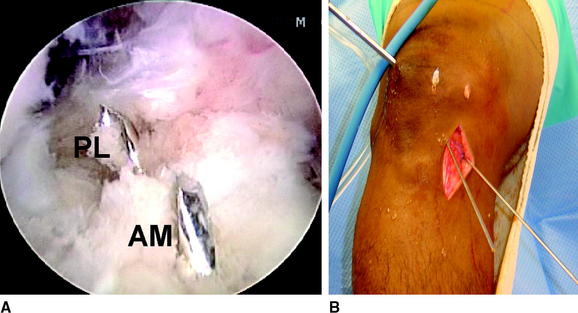

Attention is then redirected to the notch. Any obstructing fat pad or ligamentum mucosum is removed with the shaver or ArthroCare Coblation device. The bundles of the ACL are carefully dissected with a small ArthroCare Coblation device to fully appreciate the injury tear pattern. Because the two bundles are differentially tensioned depending on the position of the knee at the time of injury, the tear pattern can be quite different for each bundle.18 We are currently performing a prospective study to correlate the preoperative examination (i.e. KT-1000, examination under anesthesia [pivot-shift and Lachman maneuvers]) with the individual tear pattern of each bundle (Fig. 25-4). The remnant of the ACL bundles is then débrided from both their femoral and tibial insertions. The ArthroCare Coblation device is used to mark the AM and PL femoral and tibial footprints (Fig. 25-5). No notchplasty is performed.

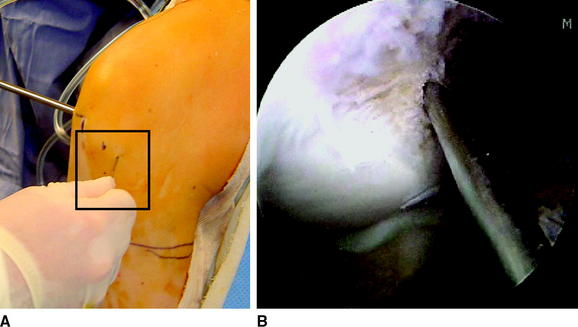

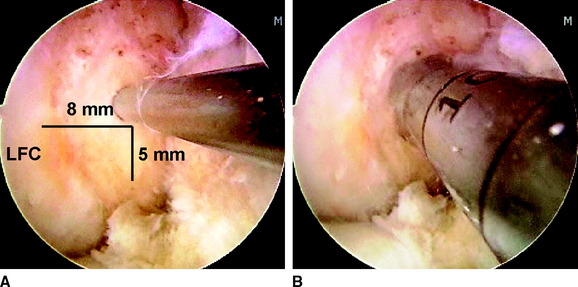

An 18-gauge spinal needle is directly visualized as it passes from the location of the low AM portal onto the medial face of the lateral femoral condylar notch in the region of the previously marked PL bundle (Fig. 25-6). Once satisfactory trajectory for the PL bundle with the spinal needle has been determined, remove the spinal needle and make the low AM portal with an 11 scalpel blade angled upward to avoid cutting the anterior horn of the medial meniscus. Pass a  -mm Steinman pin via the low AM portal onto the medial face of the lateral femoral condylar notch. Place the pin approximately 8 mm posterior to the anterior articular margin and approximately 5 mm superior to the inferior articular margin of the lateral femoral condyle. Once correct placement of the pin has been obtained, bring the knee into approximately 120 degrees of hyperflexion and tap it into place with a mallet (Fig. 25-7). Ensure that the pin did not penetrate the medial meniscus, and then slide the 7-mm acorn reamer over the Steinman pin and have it rest against the medial face of the lateral femoral condylar notch. Ream to a depth of 25 mm. Then place the Endobutton drill within the previously reamed canal, and drop your hand before starting the drill, which will maximize the PL tunnel length. With the knee still flexed at 120 degrees, have your assistant place his or her hand on the lateral aspect of the knee and push the biceps tendon inferiorly, which will deflect the common peroneal nerve away from the drill trajectory. Barely perforate the lateral femoral cortex with the Endobutton drill, and quickly retract it backward to minimize the risk of injury to the common peroneal nerve. Measure the transcondylar length, and choose the appropriately sized continuously looped Endobutton. If the length is greater than 35 mm, replace the 7-mm acorn reamer within the PL tunnel and dilate the tunnel depth to 30 mm by hand. There should be at least 15 mm of graft tissue within the tunnel (Fig. 25-8).

-mm Steinman pin via the low AM portal onto the medial face of the lateral femoral condylar notch. Place the pin approximately 8 mm posterior to the anterior articular margin and approximately 5 mm superior to the inferior articular margin of the lateral femoral condyle. Once correct placement of the pin has been obtained, bring the knee into approximately 120 degrees of hyperflexion and tap it into place with a mallet (Fig. 25-7). Ensure that the pin did not penetrate the medial meniscus, and then slide the 7-mm acorn reamer over the Steinman pin and have it rest against the medial face of the lateral femoral condylar notch. Ream to a depth of 25 mm. Then place the Endobutton drill within the previously reamed canal, and drop your hand before starting the drill, which will maximize the PL tunnel length. With the knee still flexed at 120 degrees, have your assistant place his or her hand on the lateral aspect of the knee and push the biceps tendon inferiorly, which will deflect the common peroneal nerve away from the drill trajectory. Barely perforate the lateral femoral cortex with the Endobutton drill, and quickly retract it backward to minimize the risk of injury to the common peroneal nerve. Measure the transcondylar length, and choose the appropriately sized continuously looped Endobutton. If the length is greater than 35 mm, replace the 7-mm acorn reamer within the PL tunnel and dilate the tunnel depth to 30 mm by hand. There should be at least 15 mm of graft tissue within the tunnel (Fig. 25-8).

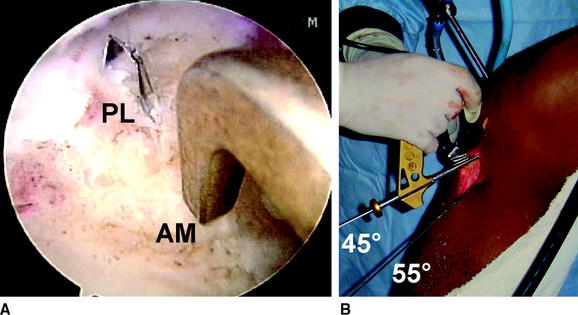

Make a 3- to 4-cm incision over the AM surface of the tibia for creation of the tibial tunnels and passage of the grafts. This is in a location midway between the tibial tubercle and the posteromedial border of the tibia. Dissect the soft tissues both medially and laterally for easy access to the future tibial AM and PL tunnels. Identify the tibial PL footprint, which is located just medial to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and anterior to the PCL. The footprint should have been previously marked with the ArthroCare Coblation device. Place the ACL director guide (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) at 55 degrees with the tip centered within the PL tibial footprint (Fig. 25-9). Drill a  Steinman pin through the guide and within the joint so that a few millimeters are visible. Identify the AM tibial footprint with the ArthroCare Coblation device, which is a couple of millimeters anterior to the ideal single-bundle reconstruction location: the posterior aspect of the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus, downward sloping side of the medial tibial eminence, and approximately 7 mm anterior to the PCL. Reset the ACL director guide to 45 degrees and place it within the previously marked AM tibial footprint (Fig. 25-10). Drill a second

Steinman pin through the guide and within the joint so that a few millimeters are visible. Identify the AM tibial footprint with the ArthroCare Coblation device, which is a couple of millimeters anterior to the ideal single-bundle reconstruction location: the posterior aspect of the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus, downward sloping side of the medial tibial eminence, and approximately 7 mm anterior to the PCL. Reset the ACL director guide to 45 degrees and place it within the previously marked AM tibial footprint (Fig. 25-10). Drill a second  Steinman pin through the guide and within the joint so that a few millimeters are visible. Note that the PL tibial guide pin is quite vertical in comparison with the AM tibial guide pin, which is quite horizontal. This pin attitude also prevents impingement within the notch because the PL tunnel is centered within the knee and the AM tunnel is horizontal. Once again, no notchplasty is necessary. The PL tibial guide pin also enters the AM surface of the tibia more posteromedially than the AM tibial guide pin, which is more lateral and centered (Fig. 25-11). Retract the skin on the tibia to allow placement of a 7-mm reamer over the PL tibial guide pin, and place a curette within the joint overlying the PL pin to protect the articular surfaces. Ream the PL tunnel, and remove debris with a shaver. Then place the 8-mm reamer over the AM tibial guide pin, and once again place a curette overlying the pin to protect the articular surfaces. Ream the AM tunnel, and remove debris with a shaver. There should be an approximately 1-cm bony bridge between the two tibial tunnels.

Steinman pin through the guide and within the joint so that a few millimeters are visible. Note that the PL tibial guide pin is quite vertical in comparison with the AM tibial guide pin, which is quite horizontal. This pin attitude also prevents impingement within the notch because the PL tunnel is centered within the knee and the AM tunnel is horizontal. Once again, no notchplasty is necessary. The PL tibial guide pin also enters the AM surface of the tibia more posteromedially than the AM tibial guide pin, which is more lateral and centered (Fig. 25-11). Retract the skin on the tibia to allow placement of a 7-mm reamer over the PL tibial guide pin, and place a curette within the joint overlying the PL pin to protect the articular surfaces. Ream the PL tunnel, and remove debris with a shaver. Then place the 8-mm reamer over the AM tibial guide pin, and once again place a curette overlying the pin to protect the articular surfaces. Ream the AM tunnel, and remove debris with a shaver. There should be an approximately 1-cm bony bridge between the two tibial tunnels.

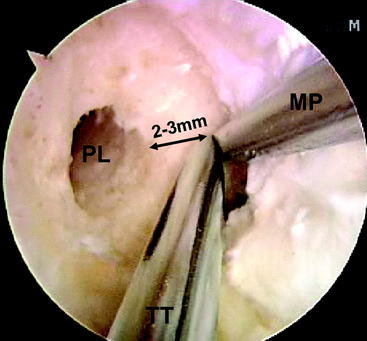

Then direct your attention to the AM femoral footprint. Guide the AM femoral tunnel off the previously made femoral PL tunnel and not off the back wall of the notch, which is traditionally done with over-the-top femoral tunnel drill guides. Place the  Steinman pin 3 mm posterior and slightly superior to the previously drilled femoral PL tunnel. The Steinman pin can be placed transtibially via the previously drilled AM tunnel or via the low AM portal, whichever will allow the proper trajectory to be low enough within the notch (Fig. 25-12). Hyperflex the knee as the Steinman pin is then tapped into place. Then place an 8-mm acorn reamer over the pin and pass it within the joint to rest against the notch wall. Ream the AM femoral tunnel to a depth of 40 mm. Place the Endobutton drill within the AM tunnel. Your hand should be dropped as the knee is maintained in the hyperflexed position to maximize tunnel length and ensure that the anterolateral femoral cortex will be perforated to allow passage of the Beath pin distal to the tourniquet. Measure the transfemoral diameter, and choose the appropriately sized closed-looped Endobutton. Ideally, there should be at least 15 to 20 mm of graft tissue within the canal.

Steinman pin 3 mm posterior and slightly superior to the previously drilled femoral PL tunnel. The Steinman pin can be placed transtibially via the previously drilled AM tunnel or via the low AM portal, whichever will allow the proper trajectory to be low enough within the notch (Fig. 25-12). Hyperflex the knee as the Steinman pin is then tapped into place. Then place an 8-mm acorn reamer over the pin and pass it within the joint to rest against the notch wall. Ream the AM femoral tunnel to a depth of 40 mm. Place the Endobutton drill within the AM tunnel. Your hand should be dropped as the knee is maintained in the hyperflexed position to maximize tunnel length and ensure that the anterolateral femoral cortex will be perforated to allow passage of the Beath pin distal to the tourniquet. Measure the transfemoral diameter, and choose the appropriately sized closed-looped Endobutton. Ideally, there should be at least 15 to 20 mm of graft tissue within the canal.

Fig. 25-12 Anteromedial femoral guide pin landmarks. TT, Transtibial; MP, medial portal; PL, posterolateral.

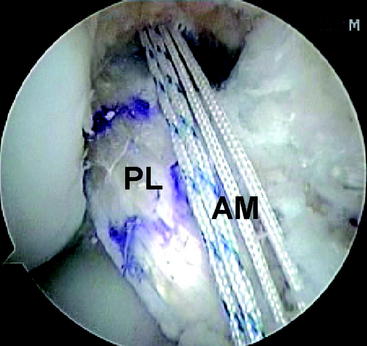

With the knee hyperflexed, place a Beath pin via the low AM portal, through the PL femoral tunnel, and out of the skin on the lateral aspect of the knee. Once again, you want to drop your hand and push the biceps tendon inferiorly as you pass the pin to protect the common peroneal nerve from injury. Tie a long looped suture through the eyelet of the Beath pin, which is pulled intraarticularly and grasped out the tibial PL tunnel with arthroscopic suture retrievers. Place the 7-mm prepared PL allograft within the long looped suture attached to the Beath pin, and pull it through the respective tibial and femoral tunnels. Flip the Endobutton, and pull the graft to ensure proper engagement. Pass the Beath pin through the tibial and femoral AM tunnels with the knee hyperflexed to ensure the pin exits the thigh distal to the tourniquet and remains sterile. Depending on the trajectory of the tunnels, the Beath pin may first need to be passed via the low AM portal through the AM femoral tunnel and the long looped suture pulled out through the AM tibial tunnel with arthroscopic suture retrievers. Place the 8-mm prepared AM allograft within the long looped suture attached to the Beath pin, and pull it through the respective tibial and femoral tunnels. Flip the Endobutton, and pull the graft to ensure proper engagement (Fig. 25-13).

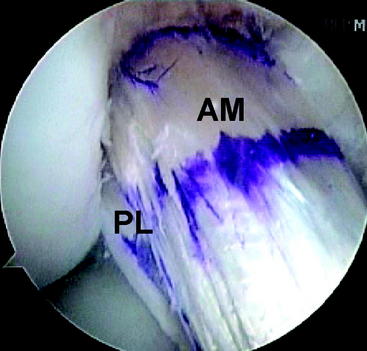

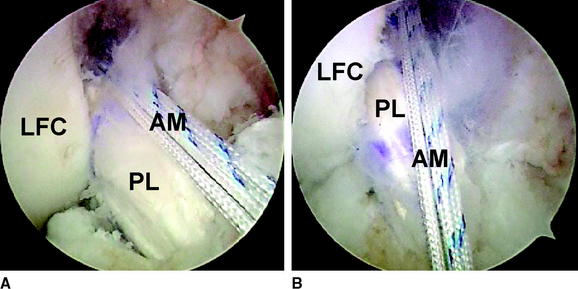

Cycle the knee through a full range of motion from approximately 0 to 120 degrees, approximately 20 to 30 times, while maintaining tension on both graft ends to remove any slack, and check the isometry. Tension the PL bundle first between 0 and 10 degrees of flexion. Then tension the AM bundle with the knee in approximately 60 degrees of flexion (Fig. 25-14). Tibial fixation is achieved with bioabsorbable interference screws, which are the same diameter as the corresponding tunnel. One staple is used as adjunctive fixation for each graft on the tibial side. Note that the reconstructed state recreates the crossing pattern of the PL and AM bundles (Fig. 25-15).

Postoperative Considerations

Rehabilitation

Postoperatively, the patient is placed in a hinged knee brace. Full weight-bearing is allowed with the knee locked in extension. Continuous passive motion (CPM) is started immediately from 0 to 45 degrees of flexion and is increased by 10 degrees per day until the maximal obtainable flexion permitted by the CPM is achieved for 2 consecutive days. This is usually after 1 to 2 weeks. The brace is unlocked at 1 week, and crutches are maintained until quadriceps control is reestablished, typically in 4 to 6 weeks. The accelerated rehabilitation protocol described by Irrgang is implemented with return to contact sports at 6 months with a brace after successful function testing.19

Results

Several in vivo functional biomechanical studies demonstrate that the kinematics are not completely restored with single-bundle reconstruction.5,6 Amis15 has demonstrated that even if the femoral tunnel is placed in a lower position than the traditionally described location, the kinematics are still not normal with regard to rotational stability. In contrast, Yagi et al14 published their results of double-bundle ACL reconstruction in a cadaveric model in which rotational stability was restored.

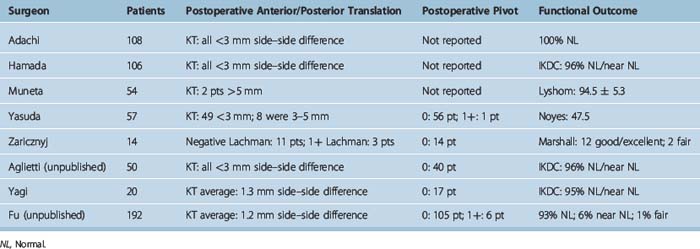

Clinical results of double-bundle ACL reconstruction surgery are still evolving (Table 25-1).12,20–25 In 1987, Zaricznyj12 published the first clinical results for double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Twelve of the fourteen patients had excellent results. In 1999, Muneta et al24 published preliminary results suggesting that the double-bundle procedure showed a better trend with respect to anterior stability. In 2001, Hamada et al22 published a 2-year follow-up on 160 consecutive patients who underwent single or bisocket ACL reconstructions, demonstrating no statistical significant difference between the two techniques for IKDC, KT measurements, or thigh muscle strength. A trend for better anterior stability was observed in the double-bundle group. No assessment of rotatory stability was mentioned. Furthermore, in 2004, Adachi et al20 performed a randomized prospective study of 108 patients (55 single bundle; 53 double bundle) with an average of 32 months of follow-up (24 to 36 months). No statistically significant difference was noted with regard to knee joint stability (KT-2000) or to proprioception. There was a statistically significant difference with regard to a decreased incidence of notchplasty for the double-bundle group compared with the single-bundle group. The authors did not obtain IKDC results or assess for rotatory stability. Aglietti et al21 have an unpublished series of 75 patients (25 single bundle, 50 double bundle) that demonstrates a lower side-to-side KT difference, a lower number of patients with a postoperative pivot shift, and better IKDC functional results for patients who underwent double-bundle ACL reconstruction. In contrast, Yagi et al23 also have an unpublished series of 60 prospectively randomized patients (20 double bundle, 20 AM reconstruction, 20 PL reconstruction). At 1 year, there were no statistically significant differences regarding side-to-side KT measurements, IKDC functional results, or patients with a postoperative pivot shift.

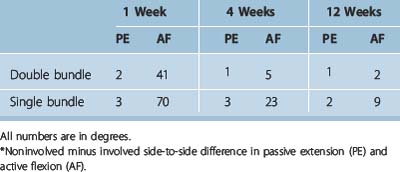

Table 25-1 Clinical Results Following Anatomical Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

The senior author has performed a total of 186 primary double-bundle ACL reconstructions to date. The average follow-up is 12 months. The average postoperative side-to-side KT measurement difference is 1.2 mm. Six patients had a 1+ pivot shift and the remainder demonstrated no pivot. In addition, we have recently compared our double-bundle ACL reconstruction, early range-of-motion data with a cohort of single-bundle reconstructions performed by the senior author. The comparison demonstrated with statistical significance that the double-bundle ACL reconstruction patients have consistently achieved earlier better range of motion at 1 week, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks postoperative follow-up (Table 25-2).

1 Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-150.

2 Freedman KB, D’Amato MJ, Nedeff DD, et al. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a metaanalysis comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:2-11.

3 Yunes M, Richmond JC, Engels EA, et al. Patellar versus hamstring tendons in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction—a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:248-257.

4 Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, et al. Prospective trial of a treatment algorithm for the management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:335-346.

5 Ristanis S, Stergiou N, Patras K, et al. Excessive tibial rotation during high-demand activities is not restored by anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1323-1329.

6 Tashman S, Collon D, Anderson K, et al. Abnormal rotational knee motion during running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:975-983.

7 Palmer I. On the injuries to the ligaments of the knee joint. Acta Chir Scand. 1938;91:282.

8 Harner CD, Baek GH, Vogrin TM, et al. Quantitative analysis of human cruciate ligament insertions. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:741-749.

9 Odensten M, Gillquist J. Functional anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament and a rationale for reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:257-262.

10 Gabriel MT, Wong EK, Woo SL, et al. Distribution of in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament in response to rotatory loads. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:85-89.

11 Mott HW. Semitendinosus anatomic reconstruction for cruciate ligament insufficiency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;172:90-92.

12 Zaricznyj B. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee using a doubled tendon graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;220:162-175.

13 Mae T, Shino K, Miyama T, et al. Single- versus two femoral socket anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction technique—biomechanical analysis using a robotic simulator. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:708-716.

14 Yagi M, Wong EK, Kanamori A, et al. Biomechanical analysis of an anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:660-666.

15 Fu FH: Rupture pattern of the anteromedial and the posterolateral bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament. Personal communication

16 Amis AA. Persistence of the mini pivot-shift after anatomically placed anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;457:203–209

17 Aglietti P, Giron F, Buzzi R, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: bone-patellar tendon-bone compared with double semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2143-2155.

18 Jonsson H, Riklund-Ahlstrom K, Lind J. Positive pivot shift after ACL reconstruction predicts later osteoarthrosis—63 patients followed 5–9 years after surgery. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:594-599.

19 Irrgang JJ. Modern trends in anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: nonoperative and postoperative management. Clin Sports Med. 1993;12:797-813.

20 Adachi N, Ochi M, Uchio Y, et al. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament—single versus double-bundle multistranded hamstring tendons. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:515-520.

21 Aglietti P. Double-bundle ACL reconstruction: single versus double incision. Personal communication

22 Hamada M, Shino K, Horibe S, et al. Single- versus bi-socket anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autogenous multiple-stranded hamstring tendons with Endobutton femoral fixation: a prospective study. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:801-807.

23 Yagi M, Hoshino Y, Nagamune K, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of double-bundle anatomic, single-bundle antero-medial, and postero-lateral ACL reconstructions—quantitative evaluation of the pivot shift test. In press

24 Muneta T, Sekiya I, Yagishita K, et al. Two-bundle reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using semitendinosus tendon with Endobuttons: operative technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:618-624.

25 Yasuda K, Kondo E, Ichiyama H, et al. Anatomic reconstruction of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of the anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:1015-1025.