44 Anatomic Aspects of Spinal Cord Disorders

Disorders of the spinal cord provide one of the best opportunities in clinical neurology to apply the basic science of neuroanatomy to the diagnosis and eventual management of patients having myelopathies. Detailed knowledge of spinal cord neuroanatomy is crucial to providing appropriate care to patients with the many various myelopathies as presented in the subsequent chapter (Chapter 45).

Anatomic Correlations

External Structure

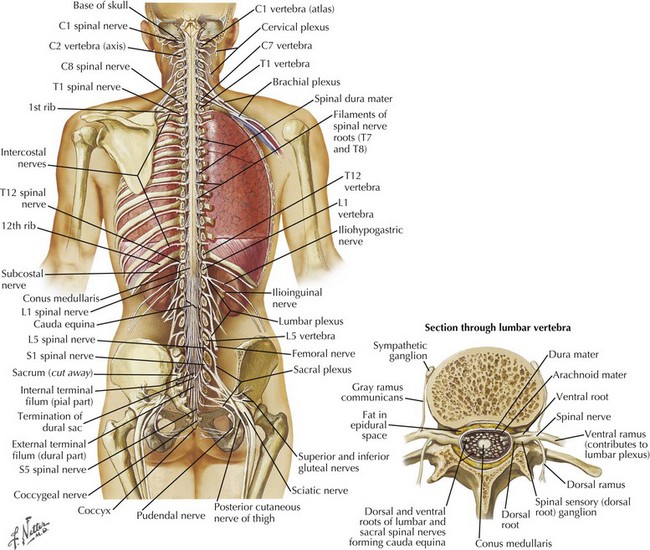

The spinal cord has major functional and teleologic importance, yet it is almost paradoxical that its total mass represents just 2% of the entire central nervous system volume. The spinal canal dimensions are slightly larger, allowing the cord to move freely within the canal during neck and back flexion/extension as its perspective changes with movement. The spinal cord per se is a cylindrical elongated structure flattened dorsoventrally, having a length of 42–45 cm (Fig. 44-1). It lies within the vertebral canal extending from the atlas, continuous with the medulla through the foramen magnum, to the level of the 1st and 2nd lumbar vertebra. Here it tapers into the conus medullaris and terminates as the cauda equina (Fig. 44-1). In conditions such as meningitis, one must not place the spinal needle above the L3 vertebra in order not to specifically damage the underlying spinal cord. It is safe to enter the spinal canal distal to this level because the spinal nerves originating from the distal cord and forming the cauda equina, as nerve roots L2-S5, are anatomically arranged so that they are gently moved aside by the passage of the needle in contrast to the fixed spinal cord that may be easily pierced by the needle insertion and thus cause significant damage.

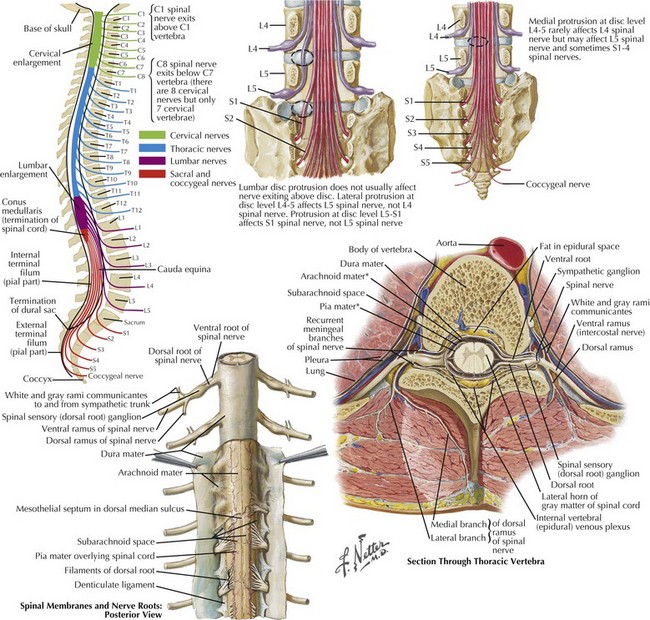

The cervical and lumbar enlargements of the spinal cord provide the nerve roots innervating, respectively, the upper and lower limbs. There are 31 pairs of spinal nerves, each having dorsal sensory and ventral motor roots that exit the cord (8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, 1 coccygeal). Although there are 7 cervical vertebrae, there are 8 cervical nerve roots (Fig. 44-2). The C1-7 roots exit above their respective vertebrae whereas C8 exits below the 7th cervical vertebra and all thoracic, lumbar, and sacral roots exit below their specific vertebrae.

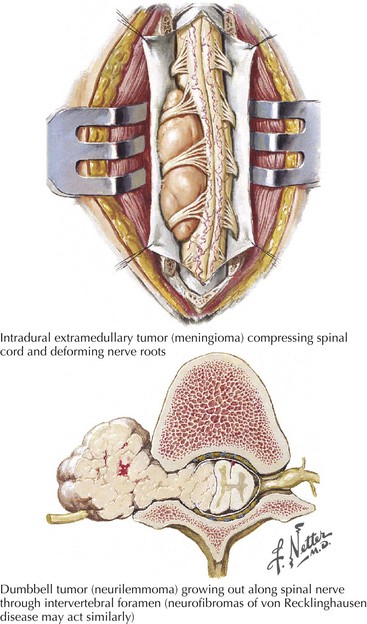

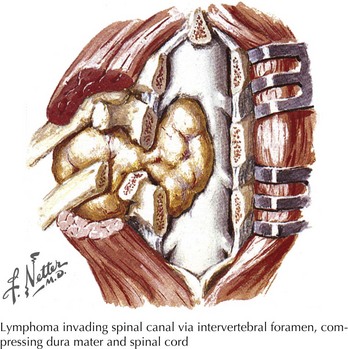

Three protective membranes, the meninges including the dura mater, being the outer layer, then the arachnoid, and the most inner one, the pia, surround the cord (Fig. 44-2). Cerebrospinal fluid flows between the arachnoid and pia. Epidural fat is present in the epidural space between the spinal canal and dura mater. When clinical myelopathies develop, these various disorders are classically categorized as intramedullary, that is, intrinsic to the cord, or extramedullary, occurring secondary to disorders extrinsic to the cord. Extramedullary disorders are further subdivided into those with either an intradural extramedullary locus or a purely extradural site of pathology.

Specific Spinal Tracts

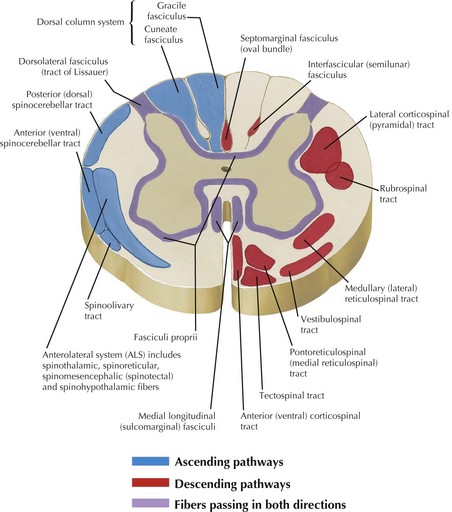

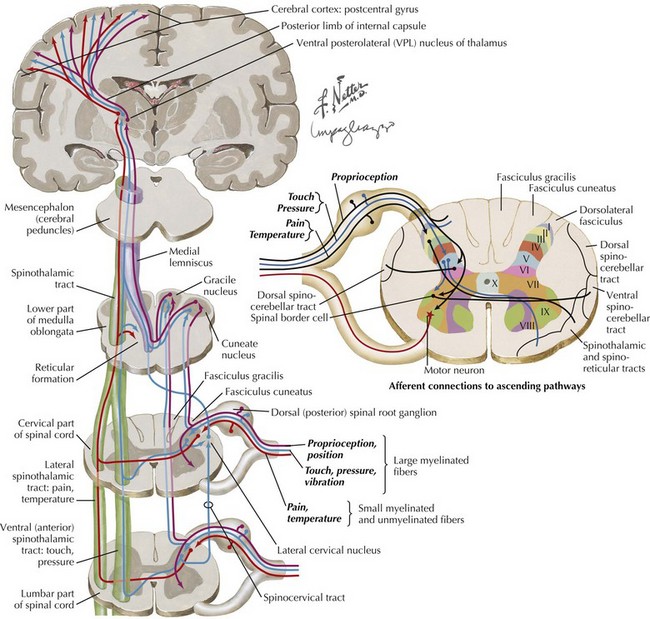

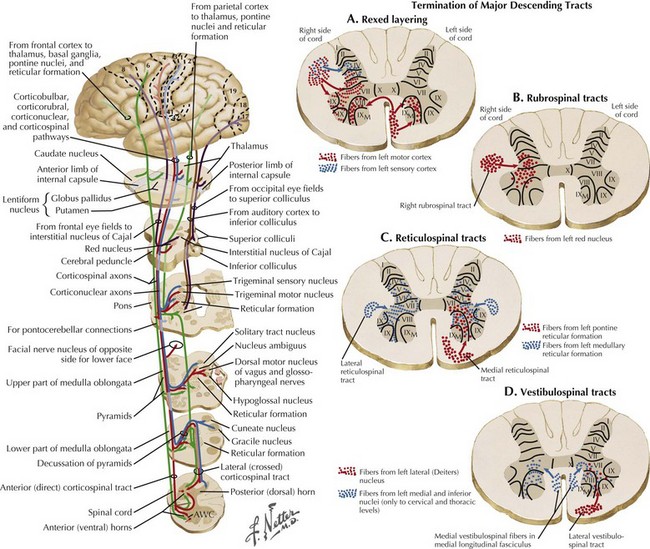

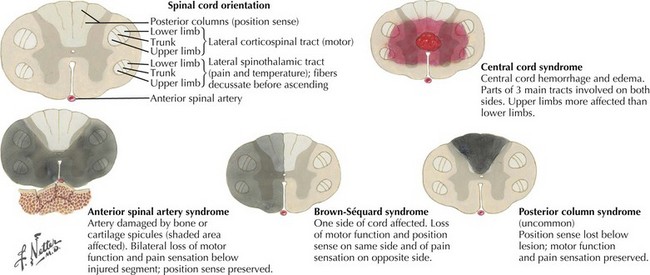

Ascending and descending tracts within the cord are interrupted at sites of cord damage (Figs. 44-3 to 44-5). The subsequent clinical sequelae develop based on the specific tracts that are affected.

Descending Motor Tracts

Corticospinal tracts are responsible for voluntary, skilled movement. They originate in the motor cortex (precentral and premotor areas 4 and 6), postcentral gyrus, and adjacent parietal cortex (see Fig. 44-5). These primary motor fibers descend via the corona radiata, posterior limb of internal capsule, pons, and into the medulla where most distally they then divide into three separate motor tracts (see Fig. 44-3). Up to 90% of these fibers descend in the lateral funiculus as the lateral corticospinal tract. Most decussate within the distal medulla; the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract is much smaller. The anterior corticospinal tract travels in the anterior funiculus, crossing within the cord.

Tectospinal, rubrospinal, and vestibulospinal tracts (see Fig. 44-3) originate in the superior colliculus, red nucleus, and the lateral vestibular nucleus, respectively. These tracts variously affect reflex postural movements, tone in flexor muscles, and facilitate antigravity and extensor muscles.

Spinal Gray Matter

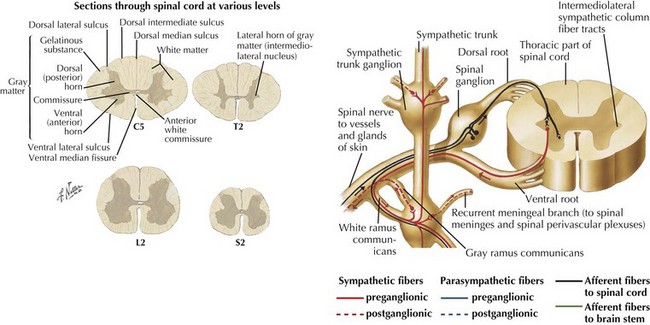

The gray matter within the central cord from dorsal to ventral respectively includes the dorsal horn, the medial commissure, and the anterior horn. Various types of sensory fibers end in different layers of the dorsal horn. The high-threshold, very thin, and unmyelinated A delta and C fibers, conducting impulses from the nociceptors, end almost exclusively in the substantia gelatinosa (lamina I and II). In contrast, nerves carrying the low-threshold mechanoreceptors subserving A beta fibers terminate in the deeper layers of the dorsal horn Rexed layers III-V. Lastly the largest, A alpha joint position sensory nerves end in the deepest layer VI of the dorsal horn (see Fig. 44-4).

Motor neurons are primarily contained within the anterior horn. The preponderant numbers of these somatic efferent neurons are primarily located within the cervical and lumbosacral enlargements (see Fig. 44-5). Here these provide the motor innervation for their respective extremities. In contrast, the ventral horn areas subsume a much smaller portion of the thoracic cord. Here the lateral horn of the gray matter becomes preeminent, where it includes the intermediolateral nucleus. Here the preganglionic sympathetic neuron perikarya are located; similar neurons are also found within the brainstem (Fig. 44-6).

Vascular Supply

Arterial

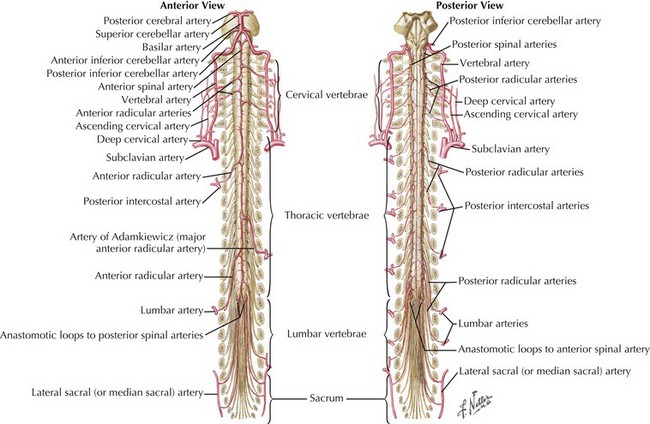

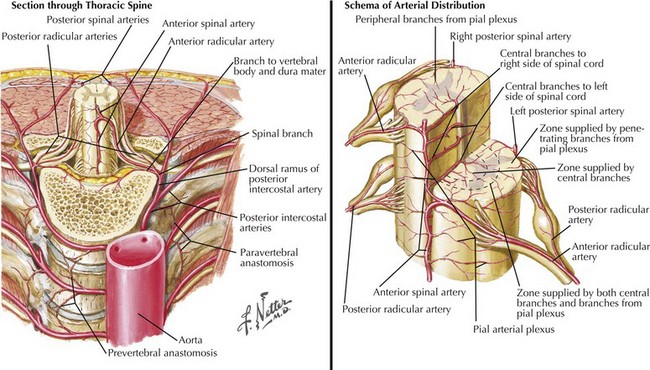

One anterior and two posterior spinal arteries course the length of the cord supplying the anterior two thirds and posterior one third of the cord, respectively (Fig. 44-7). Sulcal or central branches of the anterior spinal artery supply the central cord, whereas coronal or circumferential branches supply the ventral and lateral columns (Fig. 44-8).

Venous

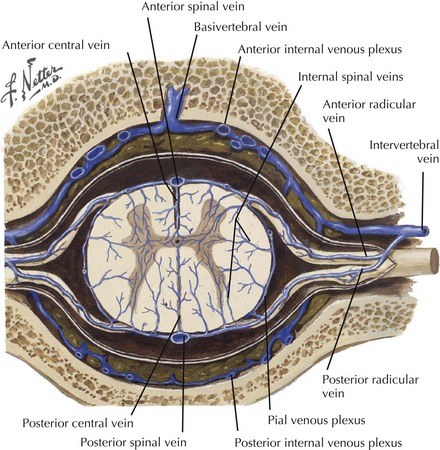

The anteromedial cord (anterior horns and white matter) is drained by the central or sulcal veins into the anterior median spinal vein that extends the length of the cord. The anterolateral, peripheral, and dorsal cord capillary plexus drains into the radial veins. The radial veins subsequently drain into the coronal venous plexus on the spinal cord surface (Fig. 44-9). This plexus, with superficial spinal cord veins (anterior median, anterolateral, posterior median, posterior intermediate), drains into medullary veins. These are anatomically linked to the nerve roots traveling through the intervertebral foramen forming the epidural venous plexus. Subsequent drainage is to the inferior vena cava, azygous, and hemizygous veins.

Pathoanatomy

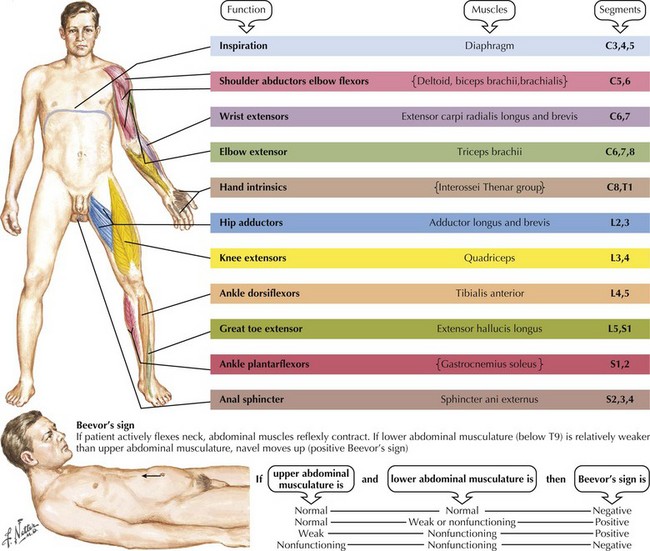

Although a magnetic resonance image often expeditiously demonstrates the site and type of spinal cord abnormality, an appreciation of the anatomy and clinical temporal profile of the precise spinal cord disorder per se is fundamental to the care of every patient presenting with a myelopathy. Focal spinal cord lesions lead to degeneration of ascending tracts above the pathoanatomic site and descending tracts below the lesions. The key to localizing the site of spinal cord involvement is identifying the exact distribution of the various motor, reflex, and sensory deficits. These findings are the clinical expression of the site of pathology. Usually, but not always, a variable degree of motor dysfunction develops. All muscles subserved by the adjacent corticospinal tracts and/or the segmental anterior horn cells are affected respective to the spinal cord level (Fig. 44-10). Even though a patient is aware of subtle changes in performance, more indolent lesions are often not evident at first examination even by a skilled neurologist. This is particularly true with segmental lesions wherein one may have a subtle foot drop (L5) or weakness of intrinsic hand muscles (C8, T1).

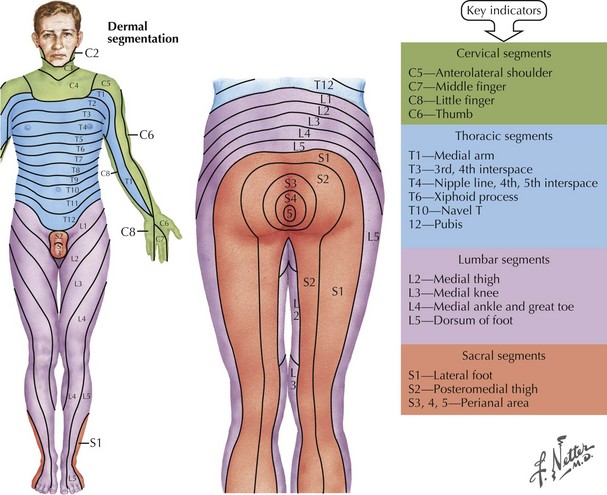

Lastly a very precise sensory evaluation is essential to the proper investigation of any potential myelopathy (Fig. 44-11). When the pathology affects the spinothalamic tract, assessment of pain and temperature sensation often provide the best evidence of a distinct spinal level of sensory loss. Often a “cord level” is a dramatic and distinct finding to elicit if one takes the time to do so. This can be elicited by using variable sensory modalities: a cold stimulus, such as the handle of a tuning fork; a safety pin; or just touching the skin (Fig. 44-12). Here the examiner takes one of these sensory tools and starting proximally or distally looks to see if there is a dramatic loss of appreciation if coming from the neck to the buttocks, or significant increased appreciation if one moves proximally in a reverse fashion. The patient’s trunk must be examined both anteriorly and posteriorly. On occasion, one sees a patient in whom such was not performed at the initial evaluation and the precise anatomic localization not appreciated—thus a temporally important opportunity for treatment delayed or missed in its entirety. It is also vital to examine sensation in the extremities. Modalities such as position sense are best evaluated by moving the great toe or a finger subtly up or down and asking the patient to report its direction of movement from its prior position.

Utilizing the data obtained from these careful motor, sensory, and reflex examinations, one can make a very logical clinical judgment as to the type of lesion, that is, intramedullary, intradural extramedullary, and extradural extramedullary. There are some very classic patterns, as summarized in Figure 44-13.

Intra-Axial Spinal Cord Pathologies

Intramedullary Loci

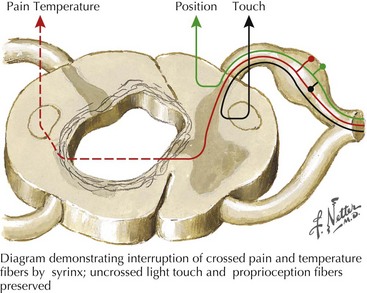

Syringomyelia, or more rarely either an intramedullary cord tumor or a central hemorrhagic spinal necrosis present with a classic dissociated sensory syndrome. Classically these patients have a “cape loss” of pain and temperature modalities. That is, the patient may note loss of temperature and pain sensation limited to their hands, arms, and shoulders with preservation of same on the trunk and lower extremities. In this instance, the decussating pain and temperature fibers, such as C5-8 fibers, are damaged as they pass under the spinal cord’s expanding central canal. Normally, these fibers join the ascending spinothalamic tracts from the legs and trunk to ascend to the brain (Fig. 44-14). Here temperature and pain sensation are intact distal to the site of the intramedullary lesion; thus there is a dissociation in the patient’s ability to perceive these basic modalities proximally at the midcervical levels but preserving same below the affected areas. Light touch and proprioception are typically preserved. Extension of the lesion into the anterior horn cells leads to segmental neurogenic atrophy, paresis, and areflexia. As the corticospinal tracts become involved, a spastic paresis develops below the level of the syrinx.

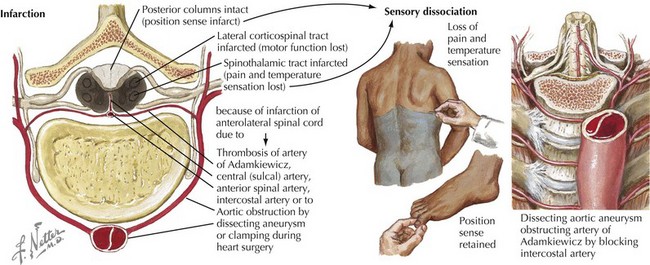

Occasionally a patient presents with a primary intramedullary lesion that primarily affects the anterior spinal cord. The primary damage occurs within the spinal cord anatomy dependent on anterior spinal artery supply. In this instance, the patient experiences damage to the lateral spinothalamic and anterior and lateral spinothalamic tracts as well as the relevant anterior horn cells (see Fig. 44-12). Typically these patients become paraparetic or paraplegic, with a complete pain and temperature sensory loss below the level of the lesion. In essence, this is an anterior two thirds transverse spinal cord lesion. Therefore, these patients characteristically have preservation of proprioception modalities (position sense) as the posterior columns remain intact. Very rarely, weakness occurs in all four extremities when the cervical cord is infarcted; however, the abundance of collateral circulation at this level makes this an exceedingly rare clinical scenario. A posterior one-third myelopathy would be expected to lead to a sensory ataxia, spasticity, and hyperreflexia with preserved pain and temperature and corticospinal tract function; however, this clinical picture is extremely rare.

Intradural Extramedullary

This combination of incongruous motor and sensory dysfunction is known as a dissociated clinical pattern. A good illustration is a 40-year-old woman who noted that her left leg was occasionally scuffing somewhat when she played tennis. Subsequently, she did not recognize having cut her right leg while shaving. Thus, she was developing a hemicord Brown-Sequard syndrome that proved to be at the thoracic spine level (Fig. 44-15).

Extradural Extramedullary

Focal bony lesions, often from metastases, are the typical example of an extramedullary extradural lesion. These may present subacutely or relatively acutely from pathologic fracture dislocation and extension of the tumor leading to rapid cord compromise (Fig. 44-16). Characteristically, these patients experience pain secondary to involvement of the pain-sensitive meninges, its adjacent sensory nerve roots, or the concomitant bone as occurs with metastatic cancers. Therefore, pain is one of the hallmarks of many extradural extramedullary disorders. As the size of the lesion increases, direct pressure is applied to the adjacent spinal cord, or the primary vascular supply is compromised, predominantly affecting the anterior two thirds of the cord, or both. Often these lesions expand or displace cord tissue acutely, essentially leading to a pathophysiologic cord transection. Thus, the final clinical picture may mimic a traumatic myelopathy; it is therefore of paramount importance to expeditiously evaluate these patients in order to preserve cord function.

Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel B, et al. Neurology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.

Brodal P. The Central Nervous System, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Ropper A, Samuels M. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Rowland LP, Pedley TA. Merritt’s Neurology, 11th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2010.