54 Anatomic Aspects of Cerebral Circulation

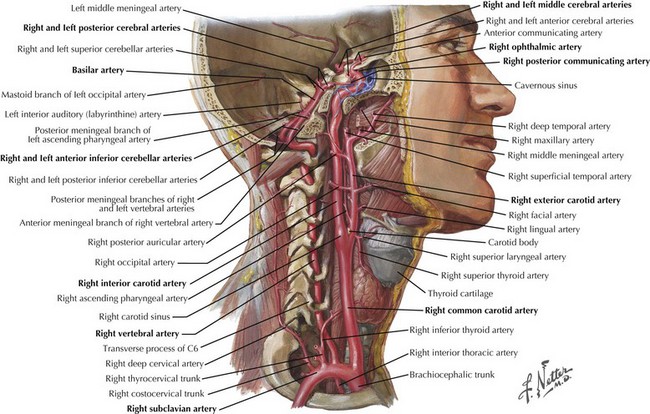

The brain and meninges are supplied by arteries derived from the common carotid artery (CCA) and vertebrobasilar system (Fig. 54-1). The right CCA usually originates from the brachiocephalic trunk, whereas the left CCA originates directly from the aortic arch. Both vertebral arteries (VAs) originate from the subclavian arteries. The morphologic variants of the CCA and VAs usually are not clinically significant.

The Carotid Artery System

External Carotid Artery

At its origin, the ECA deviates anteriorly and medially in relation to the ICA in the neck and provides many branches to the neck (superior thyroid, ascending pharyngeal arteries) and face (lingual and facial arteries). As the artery ascends, occipital and posterior auricular branches supply the scalp in their named areas. The occipital artery, however, also has several meningeal branches that supply the posterior fossa and dura. Within the substance of the parotid gland, the ECA divides into its two terminal branches, the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries. The superficial temporal artery is the main supply to the scalp over the frontoparietal convexity and its underlying muscles. The more proximal branches also supply the masseter muscle. The superficial temporal artery is commonly involved in giant cell arteritis, an important consideration in the elderly with headaches, and can be palpated anterior to the tragus and in the temporal area (Chapter 11).

The maxillary artery supplies the face and, through its middle meningeal branch, provides most of the blood supply to the dura mater covering the brain. The middle meningeal artery is often implicated in the formation of epidural hematomas in patients with temporal or parietal bone skull fractures (Chapter 59).

Internal Carotid Artery

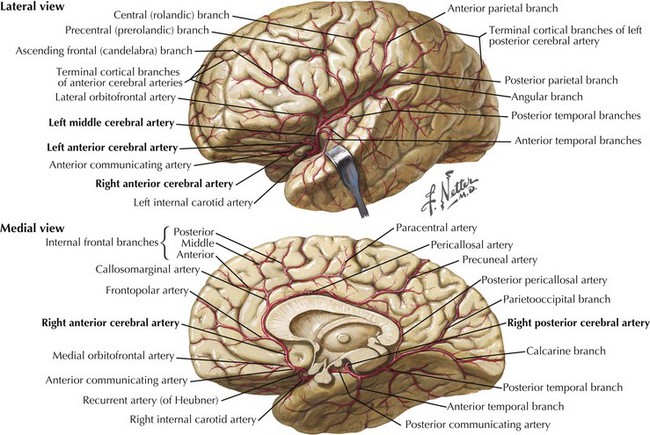

The MCA originates from the supraclinoid carotid stem and, subsequently, travels laterally to the sylvian fissure as the main-stem M1 segment, giving off lenticulostriate branches to the basal ganglia. As the MCA approaches the sylvian fissure, it usually divides into two large trunks, the superior and inferior divisions. Occasionally, the MCA trifurcates, and a middle trunk is also present. Different branches supply the frontal (orbitofrontal, ascending frontal, precentral, and central branches), parietal (anterior and posterior parietal and angular branches), and temporal (anterior and posterior temporal) lobes. The orbitofrontal, ascending frontal, precentral, and central branches usually arise from the superior division of the MCA, whereas the angular, anterior and posterior temporal branches arise from the inferior division. The anterior and posterior parietal branches can arise from either division (Fig. 54-2). The MCA stem or its distal bifurcation point are classic sites where large cerebral artery emboli lodge and are sometimes amenable to emergent intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy.

Vertebrobasilar Arteries

The vertebral arteries (VAs) usually originate from the subclavian arteries on either side (see Fig. 54-1). They have 4 portions: 3 extracranial and one intracranial. From their origin, the VAs travel posteriorly (prevertebral segment) and enter the transverse foramen of the sixth cervical vertebrae. They then extend superiorly to exist at C2 (cervical segment), sharply turning posteriorly around the auricular process of the atlas (atlantic segment), then proceeding rostrally, piercing the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane and the dura mater to enter the intracranial cavity through the foramen magnum (intracranial or intradural segment). The vertebral arteries are prone to dissection at their entry and exit sites through the vertebra and are prone to temporal arteritis right at the dural junction.

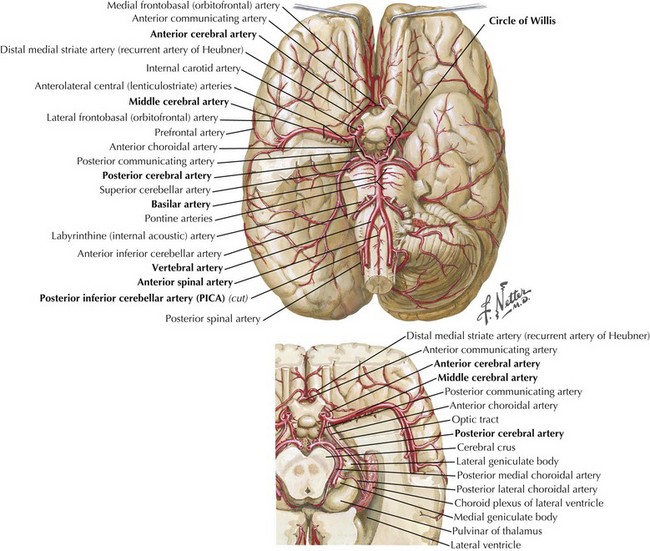

The intracranial segments course anteriorly lateral to the medulla, then ascend medially to the pontomedullary junction, where they unite at the pontine midline to from the basilar artery (Fig. 54-3).

The anterior spinal artery arises from paired medial VA branches just before the basilar junction unites in the midline to form a single vessel running the full length of the spinal cord caudally in the anteromedial sulcus. It also supplies the medial portions of the medulla; however, adequate collateral circulation in this location makes the medial medullary syndrome rare. In contrast, the anterior spinal artery within the cord is crucial to spinal cord function, and its occlusion leads to an anterior spinal artery syndrome (Chapter 45). The posterior spinal arteries arise from the PICAs or intracranial VAs and run caudally, supplying the posterior and lateral aspect of the spinal cord.

The basilar artery is particularly prone to atherosclerotic deposition throughout its length, and at its extremes can cause either severe stenosis or occlusion, or formation of a fusiform aneurysm by weakening the vessel wall. The rostral end of the basilar, just before bifurcating into the PCAs, is the site most likely to be occluded by an embolus leading to the classic “top of the basilar” syndrome (Chapter 55). Similarly, this is one of the most common sites for berry aneurysms within the vertebrobasilar system.

Cerebral Sinuses and Veins

Surrounded by dura, cerebral sinuses and veins are the venous structures of the brain. They typically contain inpouchings of arachnoid cells, called arachnoid granulations, which allow CSF drainage. These granulations function as one-way valves and are pressure dependent. Malfunction of these valves can occur in subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis, leading to normal pressure hydrocephalus. The main venous sinuses include the superior and inferior sagittal sinuses, the straight sinus, the transverse sinuses, the sigmoid sinuses, the occipital sinus, the cavernous sinuses, the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses, and the sphenoparietal sinuses. Acute or subacute cerebral venous thrombosis can be the cause of a wide range of neurologic pathology from isolated chronic headache to venous infarction with seizures to obtundation and coma. Anatomic images and full discussion of this subject are provided in Chapter 56.

Damasio H. A computed tomographic guide to the identification of cerebrovascular territories. Arch Neurol. 1983;40(3):138-142.

Netter FM. The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations. Vol 1: Nervous System. Part 1: Anatomy and Physiology. Teterboro, NJ: Icon Learning Systems; 2001.

Tatu L, Moulin T, Bogousslavsky J. Arterial territories of the human brain. Neurology. 1998;50:1699-1708.