CHAPTER 41 Anatomic approach for tip problems

History

A successful treatment plan depends on an understanding of the following:

• The anatomic variations of the soft tissues and cartilaginous framework of the tip as well as their contributions to the external nasal appearance.

• The factors that are responsible for the support of the tip and how they are interrelated.

• The effect that each surgical modification or combination of modifications has on the final surgical result.

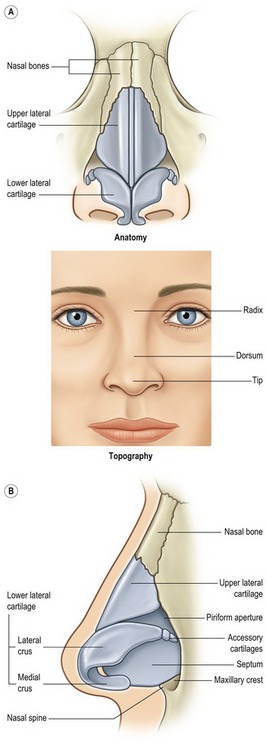

Anatomy

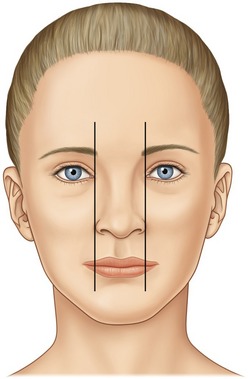

A pleasing appearing nasal tip will usually have the following components. The basal width of the nose should be approximately the same as the intercanthal distance (Fig. 41.1).

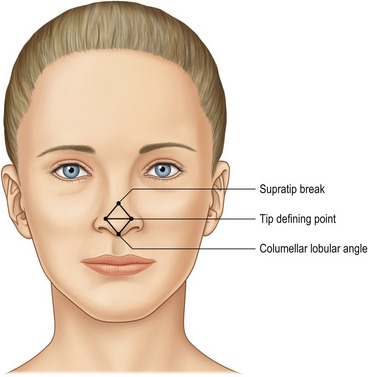

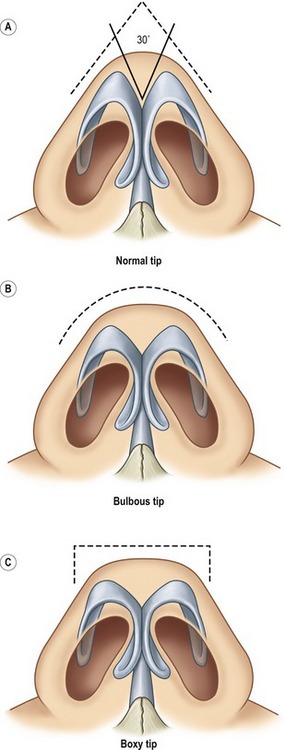

Four landmarks should be highlighted on the frontal view: the supra-tip break, the paired tip defining points and the most inferior portion of the infra-tip lobule. These points should divide the tip complex into two equal and opposite equilateral triangles (Fig. 41.2).

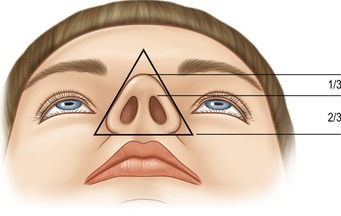

From the basal view, the base should form an equilateral triangle with rounded corners, side walls and a lobule to nostril ratio of 1 : 2. The nostrils are routinely oval in shape with a slight superior-medial orientation (Fig. 41.3).

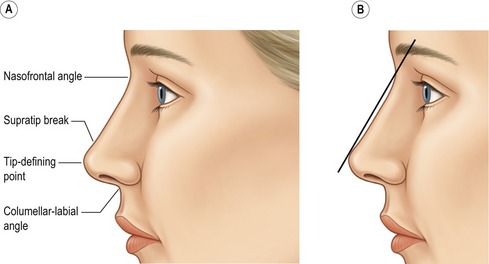

The straight alar side-walls should slope medially upward to the paired tip defining points (TDP). On lateral view, a straight line drawn from the naso-frontal angle to the TDP should be 2–3 mm anterior to the nasal dorsum in females. This should result in a slight supra-tip break. Generally, this is not necessary in males and one should err on the side of a straight nasal dorsum to prevent the nose from appearing feminine (Fig. 41.4).

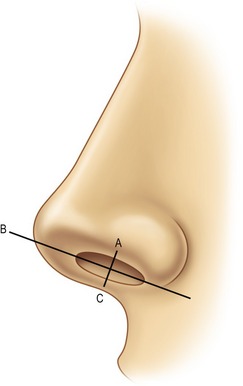

The alar-columellar relationship is measured from the naso-labial angle – which is defined by a line drawn through the most anterior and posterior portion of the nostril on profile. The nostril show should never be less than 1 mm or greater than 4 mm (line A–B and line B–C) (Fig. 41.5).

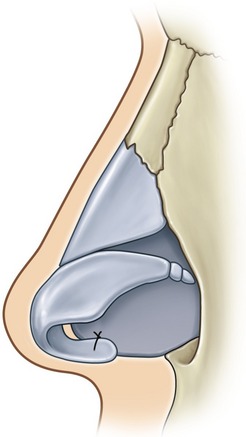

The nasal tip cartilages are comprised of paired lower lateral cartilage complexes (LLCC) on both sides which connect the lateral ends of the lateral crura to the pyriform aperture by the accessory cartilages. Each LLCC is comprised of a medial and a now named intermediate crus (formerly thought to be the anterior portion of the medial crus) which extends from the columellar-lobular angle to its junction with the lateral crus. The dome of the LLCC, which is typically rounded, is the most projecting part of the tip. The highest point on the dome is termed the tip defining point (TDP) (Fig. 41.6).

Fig. 41.6 A, It is of critical importance to appreciate the effect the underlying osseocartilaginous framework has on the overlying nasal skin. B, Tip shape results from the combined effect of the paired lower lateral cartilages, upper lateral cartilages caudal septum, septal angle and associated ligaments and skin.

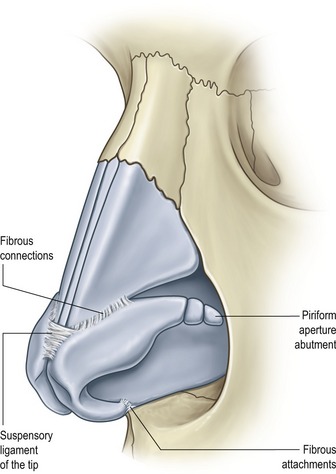

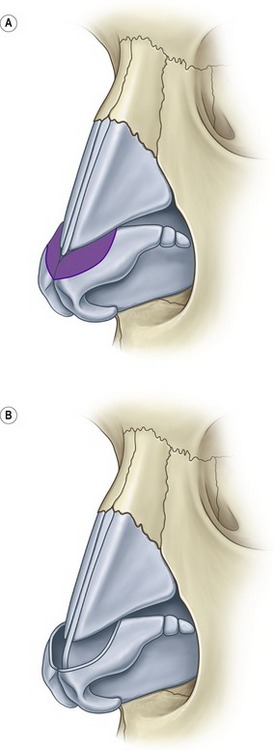

The LLCC are the major supporting factors of the tip. The larger, more rigid they are the more influence they have in this role. The LLCC are in turn supported by three ligamentous attachments to adjacent structures. One attachment is between the feet of the medial crura and the septum, another between the cephalic border of the lateral crus and the caudal border of the adjacent upper lateral cartilage (ULC) and the third from the medial cephalic border of the lateral crus across the septal angle to the medial cephalic border of the opposite lateral crus. Other structures adding to the support are the fibro-fatty tissue between the feet of the medial crura and the anterior maxilla, the septal angle and the tip skin (Fig. 41.7).

The shape of the tip is determined by the LLCC and their supporting structures.

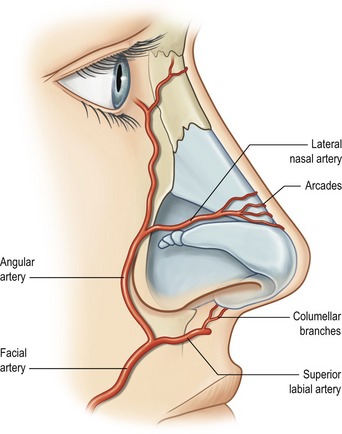

The blood supply to the nasal tip skin is supplied primarily by the angular and superior labial arteries, which derive from the facial artery. The lateral nasal artery originates from the angular artery; it then passes medially along the cephalic margin of the lateral crura and gives off caudal branches toward the nostril rim. The columellar artery takes off from the superior labial artery and courses up the columella to the region between the domes. The lateral nasal and columellar arteries then anastomose over the domal region, forming an alar arcade that runs along the cephalic margin of the lateral crura. The presence and location of these vessels has been shown to be anatomically consistent. Collateral flow may also be provided by the ophthalmic system, but this is less reliable (Fig. 41.8).

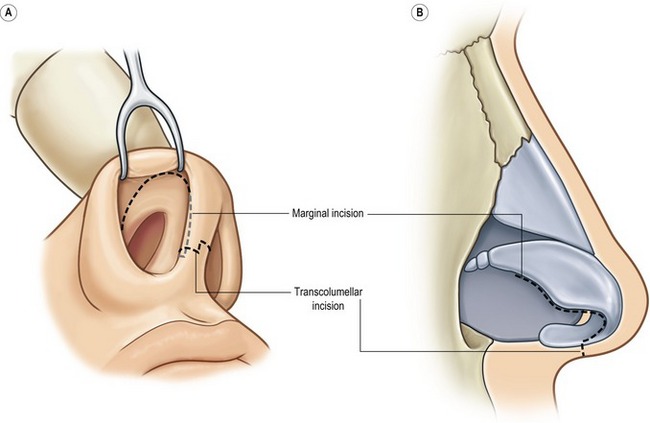

Technical steps

Using the open approach with bilateral marginal incisions connected by a staggered transcolumellar incision, the skin is elevated off the underlying cartilaginous and bony framework with sharp pointed scissors and periosteal elevators staying directly against the osseocartilaginous framework. The nose is then inspected to confirm or alter the clinical preoperative analysis (Fig. 41.9).

Fig. 41.9 Standard incisions employed in the open approach. (Infracartilaginous incision combined with staggered transcolumellar incision.)

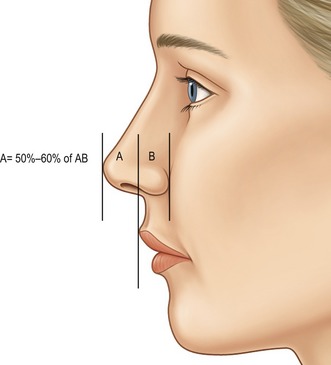

Tip projection

Tip projection can be evaluated by drawing a line from the alar-cheek junction to the tip of the nose. If the upper lip projection is normal, a vertical line is drawn adjacent to the most projecting part of the upper lip. To achieve adequate tip projection, at least 50% of the horizontal line should lie anterior to the vertical line. If greater than 60% of the line lies anterior to it, the tip is considered to be over-projecting and should be reduced. If less than 50% of the tip is anterior to the vertical line, this indicates a short nose with inadequate projection that should be augmented (Fig. 41.10).

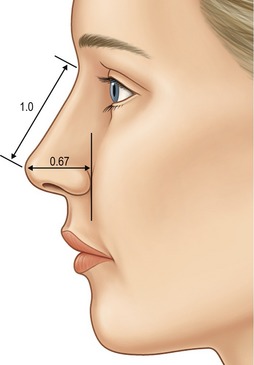

Byrd described the determination of tip projection in relation to “ideal nasal length”; ideal tip projection (distance from the alar-cheek junction to the most anterior projecting point of the nose) = 0.67 × ideal nasal length (nasofrontal angle to the most anterior projecting point of the tip) (Fig. 41.11).

Increasing tip projection

Increasing tip projection depends on the precise step-by-step execution of incremental, non-destructive techniques frequently using the open rhinoplasty approach for maximal exposure and control.

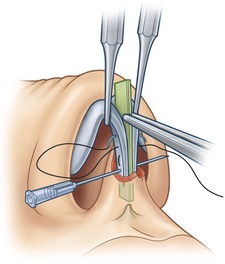

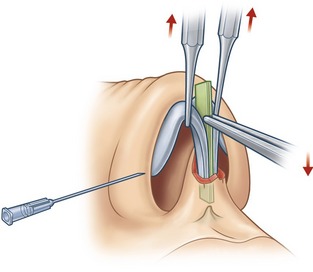

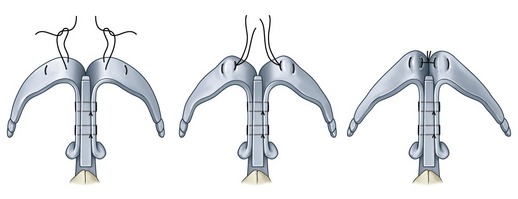

Tip projection can also be obtained by inserting a columellar strut using the open approach. Through the transcolumellar incision a pocket is undermined between the feet of the medial crura toward the nasal spine. With the medial crura advanced on the columellar strut, sutures are placed and tied on the cephalic side of the crura to secure them to the strut, resulting in increased tip projection (Fig. 41.12).

In our hands, the open approach offers a more accurate adjustment of nasal tip projection because the relationship between the medial crura and the columellar strut can be more carefully tailored. The greatest increase of tip projection is obtained when maximal opposing forces are applied to the domes and the columellar strut respectively (Fig. 41.13).

If these techniques fail to produce sufficient tip projection, a tip graft is recommended. Sheen originally described using a flat shield-shaped piece of cartilage, usually from the septum, carved so that one end was notched in the center, leaving the blunted corners approximately 6 to 8 mm apart to form the two tip-defining points. Johnson later popularized its use via the open approach where the graft could be placed more accurately and formally sutured in place. The more tip projection that is needed, the higher the tip of the graft is extended above the domes. Caution should be exercised with the use of tip grafts as many of these can become visible through atrophied or attenuated tip skin (Fig. 41.14).

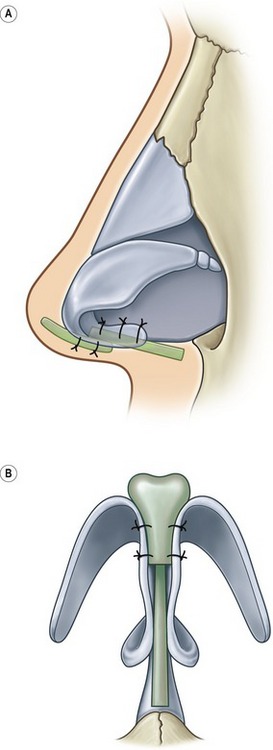

Byrd has also described a method to increase tip projection with the use of septal extension grafts which are secured at the caudal septum, extending into the interdomal space (Fig. 41.15).

Decreasing tip projection

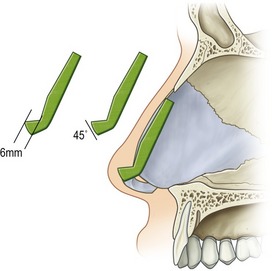

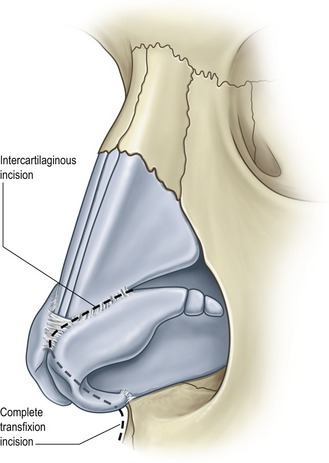

To decrease tip projection, it is necessary to reduce or eliminate some or all of the elements that support the tip. Many of these supports are divided with the routine incisions for rhinoplasty. A complete transfixion incision will disrupt the support provided by the fibroelastic attachments of the feet of the medial crura to the caudal septum. An intercartilaginous incision or resection of the cephalic margins of the lower lateral cartilages will negate the support of the attachments of the lateral crura to the upper lateral cartilages as well as the suspensory ligament connecting the cephalic margins of the domes (Fig. 41.16).

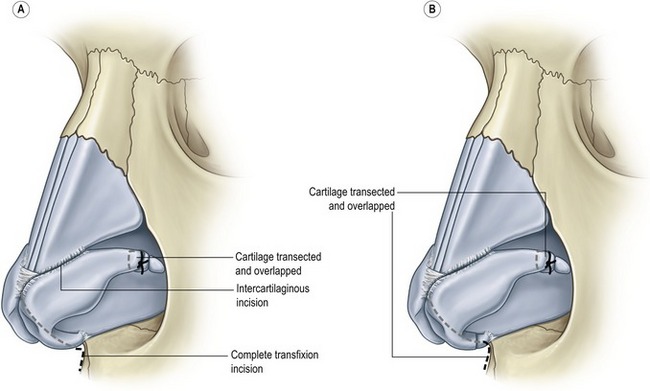

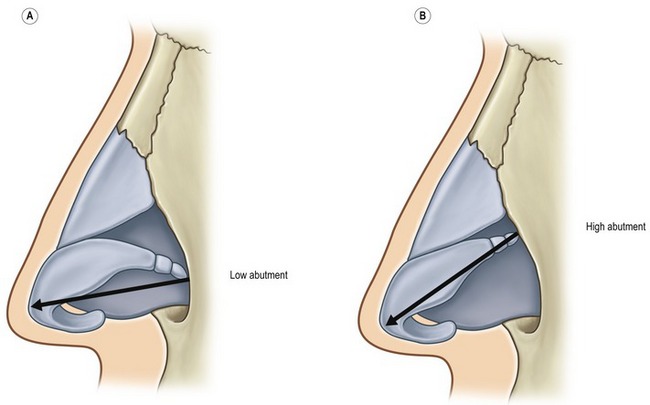

The strength and stability of the lateral crural complexes need to be carefully considered when decreasing tip projection. If the complexes are strong and firmly abut the piriform aperture, they will resist backward movement of the tip. If complete release of the supporting system of the nasal tip is unable to offer the desired decrease in tip projection, then the medial and/or lateral crura must be altered. We recommend vertically transecting, overlapping, and suturing the lateral crura at their junction with the accessory cartilages. Similarly, this can be performed on the medial crura as well if they are determined to be contributing to the unwanted tip projection (Fig. 41.17).

Substantial reduction in tip projection may result in an excessive flare in the ala that should be addressed with a formal alar base resection tailored to the individual needs of the patient.

Upward rotation of the tip

If the lateral crural complexes are oriented vertically, abutting high on the piriform aperture, they will resist upward movement of the tip. This resistance can be eliminated by interrupting the continuity of the lateral crural complex with vertical transection and repositioning (Fig. 41.18).

A columellar strut is an excellent way to maintain or increase rotation of the tip. Another technique for controlling tip rotation is to suture the lower lateral cartilages directly to the caudal septum. This is a simple maneuver that is indicated for the long nose requiring both cephalic rotation and shortening (Fig. 41.19).

Downward rotation of the tip

This can be accomplished by using any or all the following techniques: undermining of the nasal skin, release of the lower lateral cartilages from the upper lateral cartilages and nasal septum, resection of the posterior caudal septum, rotation and stabilization of the lower lateral cartilages in a posterior direction, and internal and external postoperative nasal splinting.

Reducing tip fullness and width

Decreasing fullness of the nasal tip usually requires partial resection, weakening of the lateral crura, or reshaping the lateral crura with sutures. Resecting the cephalic segments of the lateral crura will decrease tip and supra-tip fullness, but many times the remaining caudal segments will remain flared, giving the nose a bulbous appearance (Fig. 41.21).

To reduce the flare of the lateral crura, a horizontal mattress suture is placed in the dome, and the angulation is increased by tightening and tying the suture. One end of each suture can be left long and these are then approximated to reduce the angle of divergence of the LLC (Fig. 41.22).

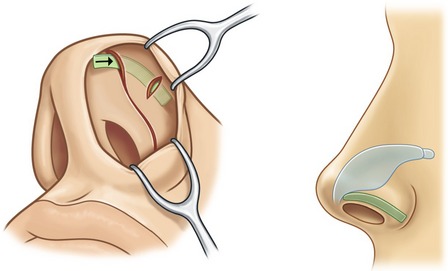

Alar notching – loss of alar to lobule transition

Alar contour grafts may be used as a simple and effective method to correct primary alar notching after correction of a tip deformity. A subcutaneous tunnel should be made with sharp angled scissors below the infracartilaginous incision. The pocket should span the alar notched area and overlay it by 2–3 mm on either side. A 2–4 mm by 8–10 mm straight segment of septal cartilage should then be contoured and placed into the pocket to correct the notching and secured medially with a single 5-0 chromic suture (Fig. 41.23).

Postoperative care

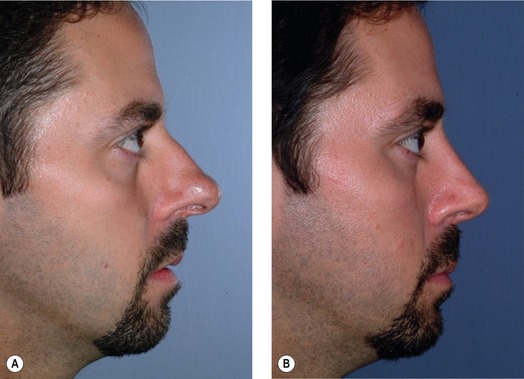

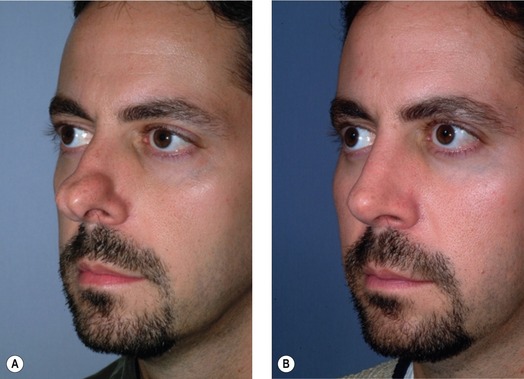

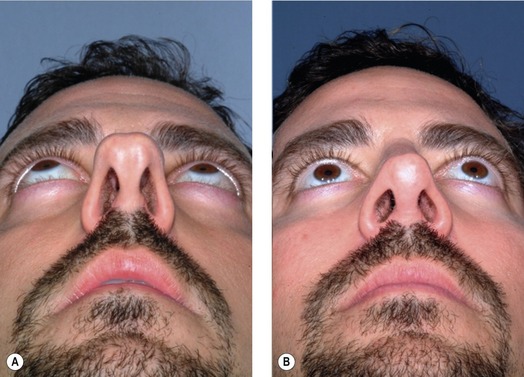

After meticulous surgical technique, preserving the new nasal shape is of paramount importance. Care must be taken to ensure the marginal incision closure does not create excessive tension on the nasal tip that distorts the nasal shape. We tape the nose with care to recreate a favorable diamond shape on the tip correlating with the supratip break, tip defining points and the infra-tip lobule. This will enhance the resolution of tip edema in an expeditious fashion. Denver splints are usually placed unless surgery is performed on the tip only. All dressings are removed at postoperative week one. Patients are followed at four-month intervals until postoperative photos are taken at the year anniversary (Figs 41.C1–41.C4).

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Accurate preoperative analysis is mandatory before proceeding with tip surgery.

• An algorithmic approach to tip support should be employed with incremental steps depending upon the degree of projection required.

• Over-resection of cartilage should be avoided with preservation of the osseocartilaginous framework to the extent that the cosmetic and functional goals can be achieved.

• If meticulously tailored, autogenous tip cartilage grafts can be successfully employed to provide additional tip projection when needed.

• Care must be taken to ensure that secondary changes in nasal shape that result from altering the tip are both anticipated and addressed.

Pitfalls

• Inaccurate preoperative analysis will result in inappropriate treatment and unsatisfactory results.

• Over-resection of the LLC can result in weakening of the cartilage and eventual collapse of the alar rims. This will result in abnormal, unattractive highlighting of the nasal tip (parenthesis deformity).

• Aggressive narrowing of the domes with transdomal mattress sutures can result in flexion at the LLC and accessory cartilage junction with possible narrowing of the nasal airway.

• Tip cartilage grafts have a tendency to cause pressure atrophy of the overlying skin with resultant visibility of the underlying graft edges over time.

• Resection of the caudal septum should be approached cautiously, as excessive resection will result in over-rotation of the nasal tip which is difficult to correct.

Summary of steps

1. During the preoperative evaluation, the ideal tip projection and rotation is established.

2. Using the open approach with bilateral marginal incisions connected by a staggered transcolumellar incision, the skin is elevated off the underlying cartilaginous and bony framework with sharp pointed scissors and periosteal elevators staying directly against the osseocartilaginous framework.

3. The nose is then inspected to confirm or alter the clinical preoperative analysis.

4. Tip projection can be evaluated by drawing a line from the alar-cheek junction to the tip of the nose. If the upper lip projection is normal, a vertical line is drawn adjacent to the most projecting part of the upper lip. To achieve adequate tip projection, at least 50% of the horizontal line should lie anterior to the vertical line.

5. Increasing tip projection depends on the precise step-by-step execution of incremental, non-destructive techniques frequently using the open rhinoplasty approach for maximal exposure and control.

6. To decrease tip projection, it is necessary to reduce or eliminate some or all of the elements that support the tip.

7. Nasal tip rotation should be analyzed by assessing the nasolabial angle, which is measured by drawing a straight line through the most anterior and posterior points of the nostrils as seen on the lateral view. The angle this line forms with a perpendicular line to the natural horizontal facial plane is the nasolabial angle.

8. Downward rotation of the nasal tip involves rotating the lower lateral cartilages caudally to displace the tip in a slightly inferior direction, thus elongating a shortened nose.

9. Decreasing fullness of the nasal tip usually requires partial resection, weakening of the lateral crura, or reshaping the lateral crura with sutures.

10. Alar contour grafts may be used as a simple and effective method to correct primary alar notching after correction of a tip deformity.

Constantian MB. Distant effects of dorsal and tip grafting in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:405.

Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Correction of the pinched nasal tip with alar spreader grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:82.

Ha RY, Byrd HS. Septal extension grafts revisited: 6-year experience in controlling projection and shape. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1929.

Johnson CM, Wyatt CT. A case approach to open structure rhinoplasty, 2nd edn. New York: Elsevier; 2006.

Peck GC. The onlay graft for nasal tip projection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:27.

Petroff MA, McCollough EG, Horn D, Anderson JR. Nasal tip projection: quantitative changes following rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:783.

Sheen JH, Sheen AP. Aesthetic rhinoplasty, 2nd edn. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing.

Sheen JH. Achieving more nasal tip projection by the use of a small autogenous vomer or septal cartilage graft. A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:35.

Tebbetts JB. Shaping and positioning the nasal tip without structural disruption: a new systematic approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:61.

Toriumi DM. New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8(3):156–185.