Anal and perianal disorders

Introduction

Anal and perianal disorders make up about 20% of general surgical outpatient referrals. These conditions can be distressing or embarrassing and patients often tolerate symptoms for a long time before seeking medical advice. The common anal symptoms are summarised in Box 30.1 and interpretation is discussed in Chapter 18.

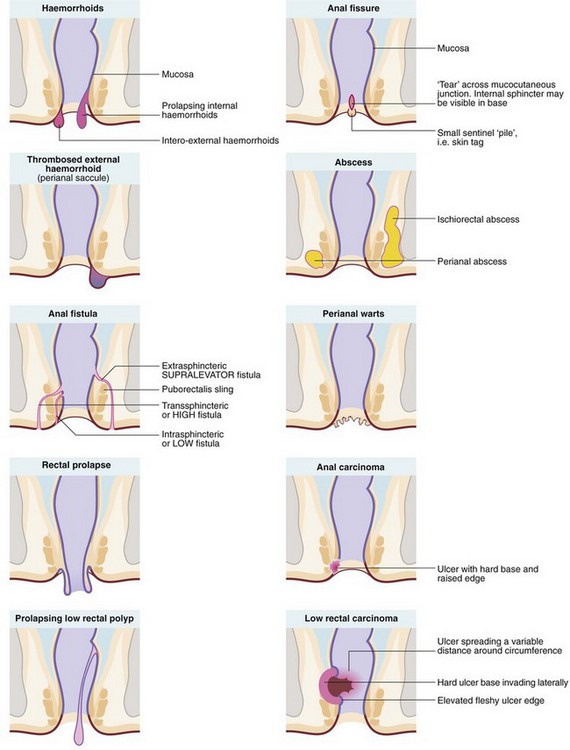

The range of anal and perianal disorders is illustrated in Figure 30.1. Haemorrhoids and other common benign conditions must be distinguished from rectal carcinoma and the rare anal carcinoma. Most anal and perianal conditions can be treated on an outpatient basis, although abscesses, and haemorrhoids that have become strangulated or thrombosed may present as surgical emergencies.

Anatomy of the anal canal

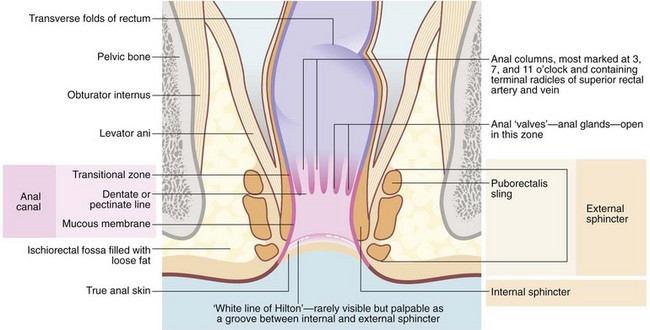

At the anal verge outside the anal canal, there is normal skin composed of stratified squamous epithelium with skin appendages—sweat glands, hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The anal canal proper is about 4 cm long, extending from the lower to the upper border of the internal sphincter (see Fig. 30.2). There are three zones, each with different lining epithelium:

• The lowest or distal zone lies between the squamous–mucocutaneous junction and the level of the anal valves at the dentate (pectinate) line. This is lined by non-keratinising squamous epithelium without skin appendages or glands; the epithelium contains some melanocytes. This area is exquisitely sensitive, for example to injection

• The anal transitional zone (ATZ). This lies between the zone of squamous epithelium below and the columnar mucosal zone above, and extends a distance varying between 0.3 and 2 cm. It consists of transitional epithelium resembling urothelium, 4–9 cell layers thick. Anal glands are present in the submucosa but there is minimal mucin production. A unique type of anal carcinoma develops from it with a viral aetiology

• The upper part of the anal canal is lined by rectal mucosa. On proctoscopic inspection, it is a dark reddish-blue where it overlies the submucosal venous plexus, becoming the typical pink of colorectal mucosa more proximally. This area of mucosa is relatively insensitive

The mucosa of the upper part of the anal canal is thrown into 6–10 longitudinal folds, the columns of Morgagni, each containing a terminal branch of the superior rectal artery and vein. The folds are most prominent in the left lateral, right posterior and right anterior sectors where the vessels form prominent anal cushions. These are important in fine control of continence. They may become pathologically enlarged to form haemorrhoids, which are complex collections of arterioles, arteries, venules, venous saccules and connective tissue. The anal columns are not readily visible on proctoscopy but the transition between glandular rectal mucosa and anal skin is clearly visible. The lymphatics of the upper anal canal drain to the pelvic and abdominal lymph node chain, whereas the lower part of the anal canal drains to inguinal lymph nodes.

Haemorrhoids

Classification of haemorrhoids

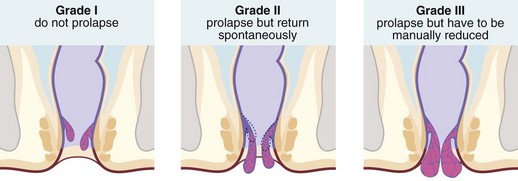

Haemorrhoids (piles) are classified into first, second and third degrees according to the extent of prolapse through the anal canal. First degree (or grade I) piles never prolapse; second degree (grade II) piles prolapse during defaecation and then return spontaneously; third degree (grade III) piles remain outside the anal margin unless replaced digitally (Fig. 30.3). Most haemorrhoids can be described as ‘internal’ because they are covered by glandular mucosa. Large neglected haemorrhoids may extend beneath the stratified squamous epithelium so their lower part becomes covered by skin. These are correctly described as ‘intero-external’ haemorrhoids, or more commonly ‘external piles’.

Symptoms and signs of haemorrhoids

The common chronic or intermittent symptoms of haemorrhoids are:

• Perianal irritation and itching (pruritus ani) caused by mucus leakage. Scratching exacerbates the problem

• Rectal bleeding (fresh blood, on the paper or separate from stool)

• Mucus leakage due to imperfect closure of the anal cushions

• Mild incontinence of flatus also due to imperfect closure of the anal cushions

Most patients reaching the surgeon have tried various anaesthetic or soothing creams and suppositories, either self-administered or prescribed by the family practitioner. The usual reasons for referral are persistent symptoms or the need to exclude malignancy as a cause of bleeding.

Surgical treatments for haemorrhoids

Injection of sclerosants or banding

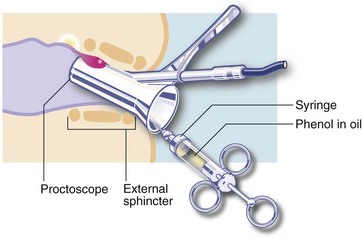

In sclerotherapy, with the aid of a proctoscope, 1–3 ml of a mildly irritant solution of 5% phenol in oil is injected submucosally around the pedicles of the three major haemorrhoids in the insensitive upper anal canal. This provokes a fibrotic reaction, effectively obliterating the haemorrhoidal vessels and causing atrophy of the haemorrhoids (see Fig 30.4). Injections are painless if the needle is placed correctly; direct injection into the haemorrhoid would be extremely painful. Sclerotherapy is usually repeated on 2–3 occasions at intervals of 4–6 weeks. Note: sclerotherapy is not suitable for patients with nut allergies because of the nut origin of the carrier oil.

Fig. 30.4 Sclerotherapy or injection of heamorrhoids

A mildly irritant solution of 5% phenol in oil is injected submucosally around the pedicle of the haemorrhoid

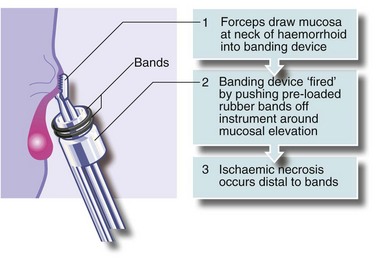

An alternative treatment is banding. A cone of mucosa just above the haemorrhoidal neck is drawn into a banding instrument, often by suction, and tight elastic bands released around the base of the cone, constricting the haemorrhoidal vessels (see Fig. 30.5). Importantly, the bands are not placed around the stalks of prolapsing haemorrhoids; this would be unbearably painful because of the somatic innervation of anal skin. The result of banding is that the haemorrhoid gradually shrinks. The bands separate with time and are passed.

Haemorrhoidectomy

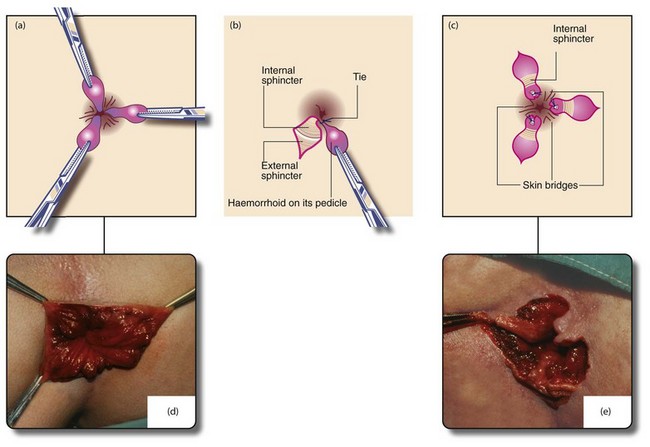

Haemorrhoidal excision is indicated for third degree haemorrhoids and for lesser degrees when other treatments have failed. The most common operation is that described by Milligan and Morgan in which the haemorrhoidal masses are excised with overlying mucosa and some skin (Fig. 30.6). This leaves skin and mucosal defects which heal by secondary intention and wound contraction. A skin bridge must be preserved between each wound to prevent the serious late complication of anal stenosis. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy enjoyed some popularity for large haemorrhoids, particularly when mucosal prolapse is a feature. It aims to restore the anatomy of the anal cushions by excising a ring of low rectal mucosa, including the engorged necks of the piles. The metal staple line remains permanently in situ, palpable digitally and sometimes causing pain. This operation requires great skill and occasionally results in serious complications; this fact plus the residual staple line are contributing to a decline in interest in the operation.

Fig. 30.6 Milligan–Morgan open haemorrhoidectomy

(a) and (d) Identification of the main haemorrhoids; the external part of each is clamped with a haemostat and retracted outwards. (b) Scissors are used to incise the skin around the external haemorrhoid, excess skin being excised at the same time. The haemorrhoid is then raised on its pedicle by dissecting it from the external and internal sphincters. The pedicle is transfixed and ligated at its base with an absorbable suture. The skin is not closed. (c) and (e) The process is repeated for the other primary haemorrhoids, ensuring that skin bridges are preserved at the anal margin between the areas resected or anal stenosis will occur as healing proceeds (‘If it looks like a dahlia, it’s a failure’). The completed haemorrhoidectomy has a ‘cloverleaf’ appearance (‘if it looks like a clover, it’s all over’). After haemostasis is ensured, wounds are dressed with a non-adherent dressing (e.g. Mepitel) and a surgical pad applied, held in place by elasticated net underpants

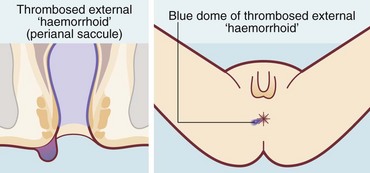

Thrombosed external haemorrhoids

A thrombosed external haemorrhoid or thrombosed external venous saccule is an acutely painful anal condition (Fig. 30.7). The onset is sudden and, if untreated, there is persistent pain lasting 1–2 weeks, worse on defaecation. On examination, a blue-black hemispherical bulge is seen in the skin near the anal margin. This is sometimes called a perianal haematoma but this is inaccurate. The condition can occur in patients with haemorrhoids but is usually seen in isolation.

Anal fissure

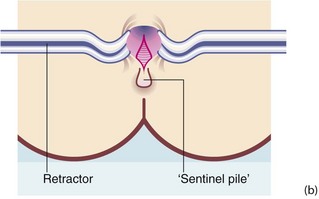

An anal fissure is a longitudinal tear in the mucosa and skin of the anal canal, sometimes caused by passing a large, constipated stool. The tear is nearly always in the posterior midline of the anal margin. The fissure causes acute pain during defaecation and sphincter spasm, both of which persist for an hour or longer. There is often a small amount of fresh bleeding at defaecation. The result is fear of defaecation and this aggravates the constipation. This history alone is diagnostic of an anal fissure. On inspection, the fissure is concealed by the anal spasm but a small skin tag (sentinel pile) may be seen at the superficial end of the fissure (see Fig. 30.8). Rectal examination is extremely painful and rarely possible unless the fissure has become chronic.

Fig. 30.8 Anal fissure

(a) Chronic anal fissure with a ‘sentinel pile’. Simple fissures are typically posteriorly located, as in this patient. (b) Explanatory diagram

Anorectal abscesses

Pathophysiology and clinical features

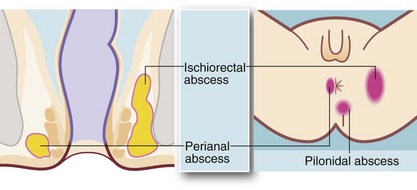

From the intersphincteric plane, infection tends to spread in one or more of three directions (see Fig. 30.9):

• Downwards between the sphincters towards the anal verge, forming a perianal abscess. This is the most common presentation and accounts for 80% of anorectal abscesses. The patient presents acutely with a painful, tender, red swelling close to the anal verge

• Outwards through the external sphincter into the loose fibro-fatty tissue of the ischiorectal fossa, forming an ischiorectal abscess. There is little barrier to spread of infection once it has entered this space and a neglected or inadequately treated abscess may become enormous. Ischiorectal abscesses make up about 15% of anorectal abscesses. The patient presents with perineal pain and systemic signs of infection. There is tenderness over the ischiorectal fossa lateral to the anus but there may be no visible redness or swelling; rectal palpation reveals a tender mass lateral to the rectum

• Upwards between the sphincters to form a supralevator abscess, involving the pararectal tissues above the pelvic floor. These make up less than 5% of anorectal abscesses and present with systemic signs of infection, rectal pain and difficulty in micturition. On rectal examination, a tender mass is often palpable near the tip of the finger

Treatment of anorectal abscesses

Incising a perianal abscess results in complete resolution in about 50% of cases; the other half develop an anal fistula (see below). The fistula is usually undetectable at the time of drainage but is recognised by a persistent discharge near the skin incision for several weeks afterwards (see Fig. 18.6).

Differential diagnosis of abscesses in the perianal area includes:

• Crohn’s disease—may cause multiple abscesses and complex fistulae (see Ch. 28) and must be excluded

• Hidradenitis suppurativa—originates in perianal apocrine glands in the skin; it is easily distinguished from deeper perianal abscesses by careful inspection and palpation. There may be multiple infected glands in the natal cleft, groins and sometimes axillae

• Pilonidal abscess—occurs in the skin of the natal cleft (see Fig. 30.9) but may mimic a true perianal abscess if near the anal margin; careful examination shows no communication with the anal canal and often the presence of embedded hairs. Treatment is by incision and drainage but further procedures may be required to treat the associated pilonidal sinus (see p. 393)

Anal fistula

The patient with a fistula typically complains of intermittent discharge of mucus or pus in the perianal region, often faecally stained. On examination, a small papilla of granulation tissue is seen on the skin within 2–3 cm of the anal margin (see Fig. 18.6). Pus may be expressed from it by compressing the underlying tract digitally between papilla and anus. This clinical picture is diagnostic of an anal fistula but this apparently trivial skin lesion is often dismissed as a pustule or an incompletely healed perianal abscess.

Most anal fistulae are simple and relatively superficial, with the internal opening located in a crypt at the level of the dentate line (well below puborectalis), most often in the posterior midline. These are known as low anal fistulae (Fig. 30.10). For successful treatment, it is essential to locate the internal opening so the entire tract can be dealt with.

Fig. 30.10 Anal fistula

A probe has been passed from the skin surface through a low anal fistula to emerge in the anal canal at the level of the dentate line. Treatment consisted simply of cutting down onto the probe, laying open the fistula along its length. The wound was left to heal by secondary intention

Goodsall’s rule helps to predict the course of a low fistula:

• If the external opening is in front of an imaginary transverse line across the anus, the fistula is likely to have a short direct tract to the anal canal

• If the external opening is behind the transverse line, the tract is likely to have a curved course towards an internal opening in the posterior midline

Assessment and treatment of fistulae requires general or regional anaesthesia. Examination under anaesthetic (EUA) is performed first. A malleable probe is gently manipulated through the fistula to try to demonstrate the internal orifice. If this is not found, hydrogen peroxide can be gently injected into the external opening. Provided the fistula is superficial and involves less than half of the sphincter bulk, treatment is by laying open the entire tract by cutting down on to the probe with diathermy, transecting the anal margin and opening the whole length of the fistula. This is known as fistulotomy and involves dividing some of the internal and external sphincter. The wound heals gradually by secondary intention. There should be no loss of faecal continence, but flatus may be less well controlled. Attempts have been made to deal with some fistulae by using tissue glues or fibrin packs but results so far are unimpressive.

Anal fistulae sometimes occur as a manifestation of Crohn’s disease. Such fistulae tend to be multiple and in the most extreme cases form a ‘pepper-pot’ perineum (see Fig. 28.8, p. 371).

Pilonidal sinus and abscess

Pilonidal sinuses tend to run a long indolent course with chronic or intermittent purulent discharge to the skin surface via one or more sinuses. Periodic acute exacerbations may progress to abscesses (Fig 30.11).

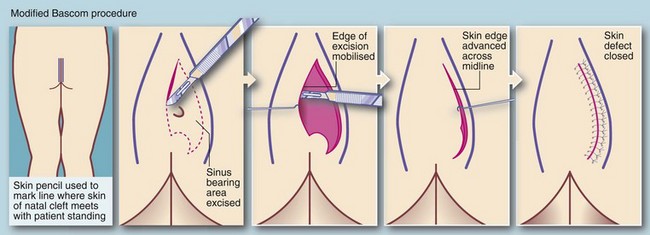

Treatment of pilonidal sinus

Definitive treatment aims to eliminate the nidus of hairs and associated cystic cavities, chronic abscesses and sinuses. At operation, obvious plugs of hair are first removed and then the sinus network is explored with probes. In the past, surgical excision left large tissue defects extending to the sacral fascia which took months to heal. Currently the favoured surgical treatment is the Bascom ‘cleft lift’ procedure which may have the secondary advantage of flattening the cleft to minimise recurrence (see Fig. 30.12).

Rectal prolapse

Rectal prolapse is a herniation of the rectum through the pelvic floor, so the mucosa and muscle wall effectively intussuscept through the anal canal (see Fig. 30.13). It is mainly seen in young children and the elderly.

Fig. 30.13 Rectal prolapse

This complete rectal prolapse was in an 80-year-old woman. It emerged spontaneously whenever she stood, causing considerable discomfort and inconvenience, to say the least!

Management of rectal prolapse

• Suture fixation rectopexy, where the rectum is mobilised and the mesorectum sutured to the sacral promontory and presacral fascia

• Resection rectopexy, where the rectum is mobilised and sutured in the same way, but a sigmoid colectomy is also performed to try to prevent the constipation that often accompanies suture fixation alone

The most popular perineal procedure is Delorme’s operation, which is appropriate for most elderly patients because of its low morbidity and mortality. It involves excising redundant rectal mucosa, plicating the rectal wall and replacing the prolapsed rectum. More radical abdominal procedures or any procedure involving an anastomosis (e.g. Altemeier’s perineal sigmoidectomy) is usually contraindicated because of greater risk.

Faecal incontinence (Table 30.1)

Table 30.1

| Underlying problem | Disorders |

| Anorectal incontinence—pudendal neuropathy (previously known as ‘idiopathic faecal incontinence’), anal sphincter and pelvic floor damage | Obstetric damage, operative damage, radiation damage, rectal prolapse, high anal fistula |

| Colorectal disease | Inflammatory bowel disease; polyps and tumours in rectum and anal canal |

| Faecal quality | Diarrhoea from any cause including infective; faecal impaction with overflow diarrhoea and incontinence |

| Rectal reservoir and sensation | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Brain and higher cerebral functioning | Neurological disorders—dementias, psychological disturbances, impaired consciousness |

| Sensorimotor pathways | Spinal injury; neurological disorders |

| Mobility and access to toilet | Enforced bed rest or impaired mobility |

Anal warts (condylomata accuminata)

Warts in the perianal region (see Fig. 30.14) have a viral aetiology (human papilloma-virus (HPV) types 6 and 11) and are generally transmitted by sexual activity. Just as cervical cancer is linked to specific strains of HPV infection, anal warts indicate an increased risk of anal canal carcinoma by virtue of their common aetiology. Immune suppression, for example in patients with organ transplants or with HIV infection, can lead to rapidly developing anal warts and progression to malignant change.