29

Anaesthesia for ENT, Maxillofacial and Dental Surgery

ENT SURGERY

Special problems are caused when the airway is shared by both anaesthetist and surgeon (Table 29.1). If bleeding is anticipated, the airway must be protected and the oropharynx may be packed to avoid contamination of the larynx with blood, pus and other debris. If a pack is used, it should either be labelled or the tail left obviously emerging from the mouth as a reminder that it must be removed at the end of the operation. The anaesthetic circuit connections are usually hidden under the drapes and may well be ‘knocked’ by the surgeon during the procedure. Anaesthetic disconnections are, therefore, a constant threat. It is important to realize that disconnections on the machine side of the capnograph sampling tube, in a patient who is breathing spontaneously, does not lead to a loss of the capnograph trace and so careful observation of the reservoir bag is mandatory.

TABLE 29.1

Potential Problems Associated with the Shared Airway

Disconnection of tracheal tube

Dislodgement of tracheal tube

Access for surgeon or anaesthetist

Airway soiling

Tube damage, e.g. laser

Lack of visual confirmation of ventilation

Eye care

Tonsillectomy

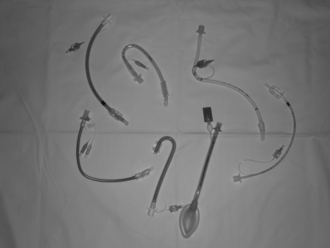

Surgical access to the pharynx requires the insertion of a Boyle Davis gag. To facilitate this, a secure airway is usually maintained with a ‘south-facing’ moulded tracheal tube (Fig. 29.1). Alternatively, a reinforced laryngeal mask airway (LMA) can be used successfully provided that the surgeon carefully avoids displacement of the LMA during the insertion and removal of the gag.

Rigid Endoscopy and Microlaryngoscopy

Occasionally, the surgeon requires access to the larynx without the presence of a tracheal tube. In this situation, oxygenation can be provided by jet insufflation of the lungs via a subglottic catheter or an attachment to the endoscope (Fig. 29.2). The catheter can be inserted into the trachea either down the endoscope or through the cricothyroid membrane. Anaesthesia is maintained using an intravenous agent, usually propofol.

Nasal and Sinus Surgery

Most nasal procedures in the UK are performed under general anaesthesia and range from simple diathermy of the inferior turbinates to prolonged cosmetic external rhinoplasty. The application of a mixture of topical local anaesthetic agents and other adjuncts (e.g. Moffat’s solution, which is a mixture of cocaine, adrenaline and bicarbonate) provides vasoconstriction before surgery. The airway must be secured to allow the delivery of oxygen and a volatile anaesthetic agent and also to protect the trachea from soiling by blood from the operative site. This can be achieved satisfactorily by the use of a reinforced LMA if there are no specific indications for tracheal intubation such as obesity or the expectation of a prolonged operation. Special attention must be paid to avoid disconnection or occlusion of the breathing system by the surgeon, or soiling of the trachea. Balanced anaesthesia is achieved using increments of a short-acting opioid or a longer-acting drug for prolonged or painful procedures. Careful pharyngeal suction is performed at the end of surgery to ensure the removal of blood and other debris which may have accumulated. The use of a pharyngeal pack is generally unnecessary but, if used, it is vital to ensure that it has been removed before emergence. Serious complications, including death, have been reported after failure to remove a throat pack. The usual principles applying to day-case anaesthesia are adhered to including preoperative assessment and postoperative care (see Ch 26).

Ear Surgery

More complex procedures are performed on the structures of the ear using a microscope (Fig. 29.3), such as tympanoplasty to repair defects in the tympanic membrane, mastoidectomy to reduce the risk of abscess and infection in the mastoid air cells and stapedectomy to improve hearing in otosclerosis. These are performed under general anaesthesia, increasingly as day-case procedures. Moderate hypotension has been employed to minimize bleeding in the operative field but hypotensive agents such as β-blockers and vasodilators have largely been superseded by the use of short-acting narcotic agents given by intermittent bolus or infusion. These provide smooth anaesthesia without variations in blood pressure associated with surgical bleeding, which can obscure the surgeon’s view through the microscope. If hypotensive anaesthesia is to be employed, care should be taken to maintain vital organ perfusion and keep the mean arterial pressure above the lower limit of autoregulation of about 55 mmHg. In general, these techniques require positive pressure ventilation with an element of muscle relaxation. A ‘south-facing’ moulded tracheal tube or reinforced LMA can be used. Nitrous oxide is avoided in the gas mixture because it can increase the pressure in the middle ear, thereby increasing the risk of graft failure. Postoperative pain is not usually severe and can usually be managed using oral analgesia, often allowing same-day discharge.

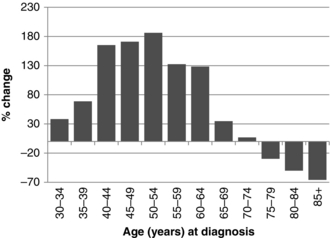

ANAESTHESIA FOR HEAD & NECK CANCER SURGERY

Tumours of the head and neck can arise from the lips, oral cavity, salivary glands, nose or nasal sinuses, oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx. Worldwide, cancer of the mouth and oropharynx is the tenth most commonly occurring form of cancer. The tumours are most commonly squamous cell carcinomas which metastasize to lymph nodes in the neck. Neck disease may present with an unknown primary which can often be identified by examination or radiological scanning. Squamous cell carcinomas are known to be associated with alcohol and tobacco use, and increase in incidence with age. However in the UK and other developed countries, for reasons which are unclear, there has been a recent increase in the incidence of oral cancer in the age group 40 to 65 years, particularly in men (Fig. 29.4). Surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy may be the primary treatment modality depending on patient factors and the staging of the disease. Combinations are often used. Surgical resection may be performed by ENT surgeons or maxillofacial surgeons depending on the site of the tumour, and the expertise of plastic surgeons may be used for the reconstruction of defects. Anaesthesia must create conditions which allow surgery to take place safely, ensuring physiological support of all systems, lack of awareness, pain control and excellent surgical access.

FIGURE 29.4 Percentage changes in incidence of oral cancer in different age groups in the UK 1975–2007. Prepared by Cancer Research UK. Original data sources:

1. Office for National Statistics. Cancer Statistics: Registrations Series MB1. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/Product.asp?vlnk=8843.

2. Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit. http://www.wcisu.wales.nhs.uk.

3. Information Services Division Scotland. Cancer Information Programme. www.isdscotland.org/cancer.

DENTAL ANAESTHESIA

Sedation

Common techniques involve the administration of an intravenous benzodiazepine or the use of nitrous oxide. Sedation may be administered by the operator before surgery or there may be a dedicated sedationist. Anaesthetists are often asked to take on this role and may use more complex techniques such as a continuous infusion of propofol using a target-controlled infusion device (Fig. 29.5).

Chesshire, N.J., Knight, D.J.W. The anaesthetic management of facial trauma and fractures. BJA CEPD Reviews. 2001;1:108–112.

Chester, A.C., Antisdel, J.L., Sindwani, R. Symptom-specific outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery: a systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:633–639.

Goldman, A.C., Govindaraj, S., Rosenfeld, R.M. A meta-analysis of dexamethasone use with tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:682–686.

Grainger, J., Saravanappa, N. Local anaesthetic for post tonsillectomy pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2008;33:411–419.

http://eng.mapofmedicine/evidence/map/epiglottitis_adult_2.html

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG60

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA1

http://rcoa.ac.uk/docs/SCSDAT.pdf

http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/docs/GPAS-headneck.pdf

Marret, E., Flahault, A., Samama, C.M., et al. Effects of postoperative, nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs on bleeding risk after tonsillectomy: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1497–1502.

Mehanna, H., Paleri, V., West, C.M., Nutting, C. Head and neck cancer – Part 1: epidemiology, presentation, and prevention. Br. Med. J. 2010;341:663–666.

Murphy, M.F., Walls, R.M. Identification of the difficult and failed airway. In: Walls R.M., ed. Emergency airway management. second ed. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:70–82.

Ravi, R., Howell, T. Anaesthesia for paediatric ear, nose, and throat surgery. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain. 2007;7:33–37.

Somerville, N., Fenlon, S. Anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain. 2005;5:76–79.

Van den Aardweg, M.T., Schilder, A.G., Herkert, E., Boonacker, C.W., Rovers, M.M. Adenoidectomy for otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;20(1):CD008282. Jan