CHAPTER 2 An introduction to surgical techniques and practical procedures

Surgical incision

When choosing an incision, the following points should be considered:

• Orientation: if possible in the lines of skin tension (Langer’s lines) or skin creases. This leads to minimal distortion and better healing

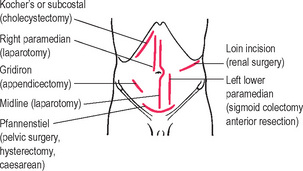

• Abdominal incision: the common abdominal incisions are shown in Figure 2.1 and the indications for such incisions are indicated on the diagram. Paramedian incisions are rarely used nowadays but are included as their scars are still seen on the abdominal wall of the older patient.

Sutures

Local anaesthesia

Tourniquets

• Empty the limb of blood (this can be performed by elevation, Esmarch bandage or rubber ‘sleeve-like’ appliances which both aim to empty the limb of blood)

• The tourniquet is placed at the proximal end of the limb (layers of crepe bandage are used underneath the cuff to protect the skin)

• For upper limb surgery an inflation pressure of 200 mmHg (or 50–75 mmHg above patient’s systolic blood pressure) and for lower limb surgery 250–350 mmHg (100–150 mmHg above patient’s systolic blood pressure).

• One hour is the recommended inflation time for upper extremity surgery and 1.5–2 h for lower extremity surgery. The tourniquet should be deflated for 10 min after the maximum recommended time, after which the tourniquet may be re-inflated for another full period.

Complications of tourniquet use include:

• Sickle crisis – in susceptible patients the build up of potassium, lactate, etc. may precipitate a sickle crisis

• Post-tourniquet syndrome – consists of non-pitting oedema, sensory loss, muscle weakness and stiffness. This may last up to a month

Diathermy

• Diathermy used in surgery is very high frequency (400 kHz–10 MHz) and uses high current intensity (as high as 500 milliamps (mA) can be used). However, home electricity is capable of inducing VF (as much as 100 mA is sufficient); this is due to the much lower frequency of around 50–60 Hz.

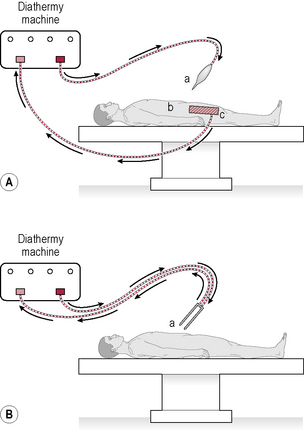

• Monopolar. This is the most common type of diathermy. An AC is produced and passed to an electrode with a small surface area (the diathermy tip). Current is passed to the tissues as heat. The current passes through the body tissue and completes the circuit by returning to a much larger surface plate, i.e. the indifferent electrode plate which is usually placed on the patient’s thigh (Fig. 2.2A). Good contact is essential. Current recommendations to improve contact include shaving hair from the skin where the plate is placed and using disposable self-adhesive diathermy plates. Monopolar diathermy is most widely used for operative haemostasis but there is wide dispersion of coagulating and heating effects, which makes it unsuitable for use near nerves and other delicate structures.

• Bipolar. There is no need for a plate and uses much less power. The two active electrodes are the tips of a pair of forceps. Current flows between the tips of the forceps and thus only affects the tissues between them (Fig. 2.2B). Bipolar diathermy is used for finer surgery where greater precision is required. There is minimal tissue damage around the point of coagulation and therefore safety in relation to nearby nerves and blood vessels.

• Coagulation. This involves sealing blood vessels. The AC output is pulsed and haemostasis occurs by a combination of cellular dehydration and protein denaturation.

• Cutting. In this form, the AC output is continuous and forms an arc between the diathermy and the tissue. The heat generated is sufficient to cause water to explode into steam. A combination of cutting and coagulation is often referred to as ‘blend’. Cutting diathermy is mainly used for dividing large muscle masses, e.g. thoracotomy and transverse abdominal incisions.

• Fulguration. A form of coagulation in which a higher voltage is used that creates sparks which arc from the diathermy to the tissues and create charring of the tissue.

Complications of diathermy include:

• Burns. Most common problem. Can occur with faulty application of the patient plate. Patient is earthed by touching a metal object (e.g. drip stand), faulty insulation on the diathermy wires, accidental activation and accidentally touching another metal object while activating diathermy (e.g. retractor).

• Interference with pacemakers. Diathermy activation may result in no pacing or the pacemaker may revert to a fixed rate. Bipolar diathermy is considered safe to use. If monopolar diathermy must be used, then the patient plate should be sited as far away as possible from the pacemaker.

• Channelling. The use of diathermy in tissues with narrow channels or pedicles can lead to the current being ‘channelled’ through a short surface area and thus high heat production. Examples of this would be in a child’s penis during circumcision or along the spermatic cord with operations on the testicle. Bipolar diathermy is safe to use.

• Direct coupling. The active diathermy comes into contact with another metal instrument (e.g. camera) that is touching tissues (e.g. bowel) and results in a burn.

• Capacitance coupling. Very rare with modern ports. Occurred when ports had a plastic portion to anchor them into the abdomen. When a current is applied through an insulated instrument within a metal tube (e.g. port), some electrical charge is transferred to the cannula. If the port is entirely metal, then there is no problem as the charge will dissipate through the abdominal wall over a large area of contact. If a plastic collar is present, then this will prevent discharge and potentially lead to burns on adjacent tissue. Diathermy injury during laparoscopic surgery may also occur with accidental activation, faulty insulation of equipment and retained heat in the instrument.

Laser

Potential risks involved with lasers include:

Laparoscopic surgery

Complications

• Dangers of pneumoperitoneum; needle/trocar injury to bowel or blood vessels; compression of venous return predisposing to DVT and PE; subcutaneous emphysema; shoulder tip pain (irritant effect of carbon dioxide producing carbonic acid locally and irritating the diaphragm with referred pain to the shoulder tip); pneumothorax (rare); pneumomediastinum (rare)

• Inadvertent injury to other structures either by dissection or diathermy or inappropriate application of clips, e.g. damage to the bile duct in cholecystectomy; uncontrollable haemorrhage

Venous access

Central venous catheterization – internal jugular vein

The following are the steps in the procedure:

• Infiltrate the skin with local anaesthetic at the level of the thyroid cartilage (three fingers breadth above the medial end of the clavicle) lateral to the carotid artery pulse

• Site of entry is at the apex of the triangle formed by the two heads of sternocleidomastoid and the clavicle

Blood gas sampling

Urinary catheterization (male)

The following are the steps in the procedure:

• Grasp penis with sterile swab, retract foreskin and clean the urethral opening and glans with antiseptic solution

Adrenaline must not be used where there are ‘end’ arteries, i.e. never on the digits or penis. It is also inadvisable to use it on other extremities, i.e. the nose, nipple or lobe of the ear. Addition of adrenaline does not increase the safe dose of bupivacaine and there is little point in using it for infiltration with bupivacaine except to reduce bleeding. The total dose of adrenaline should not exceed 500 μg. Local anaesthetic techniques should only be performed where adequate resuscitation facilities are available. Local anaesthetics should not be injected into inflamed or infected tissues where they are largely ineffective and may be responsible for further spread of infection.

Adrenaline must not be used where there are ‘end’ arteries, i.e. never on the digits or penis. It is also inadvisable to use it on other extremities, i.e. the nose, nipple or lobe of the ear. Addition of adrenaline does not increase the safe dose of bupivacaine and there is little point in using it for infiltration with bupivacaine except to reduce bleeding. The total dose of adrenaline should not exceed 500 μg. Local anaesthetic techniques should only be performed where adequate resuscitation facilities are available. Local anaesthetics should not be injected into inflamed or infected tissues where they are largely ineffective and may be responsible for further spread of infection.