Chapter 78 An Approach to Inborn Errors of Metabolism

Common Characteristics of Genetic Disorders of Metabolism

Mass Screening of Newborn Infants

Common characteristics of genetic metabolic conditions make a strong argument for screening all newborn infants for the presence of these conditions. During the past half-century, methods have been developed to screen all infants inexpensively with accurate and fast-yielding results. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is the latest technical advance in the field. This method requires a few drops of blood to be placed on a filter paper and mailed to a central laboratory for assay. A large number of genetic conditions can be identified by this method when complemented by a few equally efficient assays for other specific disorders (Tables 78-1 and 78-2). Severe forms of some of these diseases may cause clinical manifestations before the results of the newborn screening become available. It should also be noted that these methods may identify mild forms of inherited metabolic conditions, some of which may never cause clinical disease in the lifetime of the individual. Potential psychosocial implications of such findings can be devastating and deserves serious considerations. An example of this is 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase deficiency, which has been identified in an unexpectedly high frequency in screening programs using tandem mass spectrometry. The majority of these children have remained asymptomatic (Chapter 79.6).

Table 78-1 DISORDERS RECOMMENDED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF MEDICAL GENETICS (ACMG) TASK FORCE FOR INCLUSION IN NEWBORN SCREENING (“PRIMARY DISORDERS”)*

DISORDERS OF ORGANIC-ACID METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF FATTY ACID METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF AMINO-ACID METABOLISM

HEMOGLOBINOPATHIES

OTHER DISORDERS

cblA, cobalamin A defect; cblB, cobalamin B defect; CoA, coenzyme A.

* At this time, there is state-to-state variation in newborn screening; a list of the disorders that are screened for by each state is available at http://genes-r-us.uthscsa.edu/.

Table 78-2 SECONDARY CONDITIONS RECOMMENDED BY ACMG*

ORGANIC ACID METABOLISM DISORDERS

FATTY ACID OXIDATION DISORDERS

AMINO ACID METABOLISM DISORDERS

HEMOGLOBINOPATHICS

Hemoglobin variants (including hemoglobin E)

OTHERS

* The American College of Medical Genetics task force recommended reporting 25 disorders (“secondary targets”) in addition to the primary disorders that can be detected through screening but that do not meet the criteria for primary disorders.

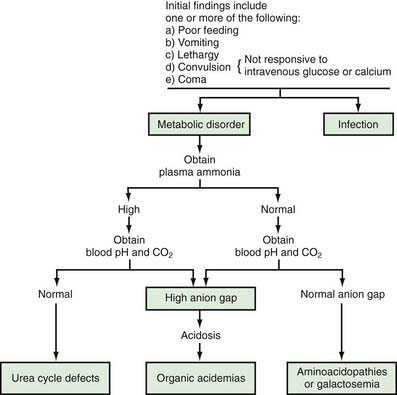

Clinical Manifestations of Genetic Metabolic Diseases

Physicians and other health care providers who care for children should familiarize themselves with early manifestations of genetic metabolic disorders, because (1) severe forms of some of these conditions may cause symptoms before the results of screening studies become available, and (2) the current screening methods, although quite extensive, identify a small number of all inherited metabolic conditions. In the newborn period, the clinical findings are usually nonspecific and similar to those seen in infants with sepsis. A genetic disorder of metabolism should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a severely ill newborn infant, and special studies should be undertaken if the index of suspicion is high (Fig. 78-1).

Signs and symptoms such as lethargy, poor feeding, convulsions, and vomiting may develop as early as a few hours after birth. Occasionally, vomiting may be severe enough to suggest the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis, which is usually not present, although it may occur simultaneously in such infants. Lethargy, poor feeding, convulsions, and coma may also be seen in infants with hypoglycemia (Chapters 86 and 101) or hypocalcemia (Chapters 48 and 565). Measurements of blood concentrations of glucose and calcium and response to intravenous injection of glucose or calcium usually establish these diagnoses. Some of these disorders have a high incidence in specific population groups. Tyrosinemia type 1 is more common among French-Canadians of Quebec than in the general population. Therefore, knowledge of the ethnic background of the patient may be helpful in diagnosis. Physical examination usually reveals nonspecific findings; most signs are related to the central nervous system. Hepatomegaly is a common finding in a variety of inborn errors of metabolism. Occasionally, a peculiar odor may offer an invaluable aid to the diagnosis (Table 78-3). A physician caring for a sick infant should smell the patient and his or her excretions; for example, patients with maple syrup urine disease have the unmistakable odor of maple syrup in their urine and on their bodies.

Table 78-3 INBORN ERRORS OF AMINO ACID METABOLISM ASSOCIATED WITH PECULIAR ODOR

| INBORN ERROR OF METABOLISM | URINE ODOR |

|---|---|

| Glutaric acidemia (type II) | Sweaty feet, acrid |

| Hawkinsinuria | Swimming pool |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaric aciduria | Cat urine |

| Isovaleric acidemia | Sweaty feet, acrid |

| Maple syrup urine disease | Maple syrup |

| Hypermethioninemia | Boiled cabbage |

| Multiple carboxylase deficiency | Tomcat urine |

| Oasthouse urine disease | Hops-like |

| Phenylketonuria | Mousey or musty |

| Trimethylaminuria | Rotting fish |

| Tyrosinemia | Boiled cabbage, rancid butter |

Diagnosis usually requires a variety of specific laboratory studies. Measurements of serum concentrations of ammonia, bicarbonate, and pH are often very helpful initially in differentiating major causes of genetic metabolic disorders (see Fig. 78-1). Elevation of blood ammonia is usually caused by defects of urea cycle enzymes. Infants with elevated blood ammonia levels from urea cycle defects commonly have normal serum pH and bicarbonate values; without measurement of blood ammonia, they may remain undiagnosed and succumb to their disease. Elevation of serum ammonia is also observed in some infants with certain organic acidemias. These infants are severely acidotic because of accumulation of organic acids in body fluids.

Treatment

Brosco JP, Sanders LM, Dharia R, et al. The lure of treatment: expanded newborn screening and the curious case of histidinemia. Pediatrics. 2010;125:417-419.

Baily MA, Murray TH, editors. Ethics and newborn genetic screening: new technologies, new challenges. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Champion MP. An approach to the diagnosis of inherited metabolic disease. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:40-46.

Dietz H. New therapeutic approaches to Mandelian disorders. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:852-853.

Goel H, Lusher A. Pediatric mortality due to inborn errors of metabolism in Victoria, Australia: a population-based study. JAMA. 2010;304:1070-1072.

McCabe LL, McCabe ER. Newborn screening as a system from birth through lifelong care. Genet Med. 2009;11:409-410.

Plass AMC, van El CG, Pieters T, et al. Neonatal screening for treatable and untreatable disorders: prospective parents’ opinions. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e99-e106.

Pollitt RJ. Newborn blood spot screening: new opportunities, old problems. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:395-399.

Santra S, Hendriksz D. How to use acylcarnitine profiles to help diagnose inborn errors of metabolism. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:151-154.

Stevenson T, Millan MT, Wayman K, et al. Long-term outcome following pediatric liver transplant action for metabolic disorders. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:268-275.

Zand DJ, Brown KM, Lichter-Konecki U, et al. Effectiveness of a clinical pathway for the emergency treatment of patients with inborn errors of metabolism. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1191-1195.