Chapter 9 Ambulatory Phlebectomy

Historical Background

Ambulatory phlebectomy (AP) is a minor surgical procedure designed to remove varicose vein clusters located close to the skin surface. Originally performed in ancient Rome, the technique was published by Robert Muller in 1966.1 In many office-based venous surgery practices in the United States, AP is performed with the use of local tumescent anesthesia. The six basic features of the technique are as follows:

Etiology and Natural History of Disease

Bulging varicose veins on the surface of the skin can originate from different sources. Identification of these sources is important because the source influences the treatment plan. Varicosities on the medial aspect of the thigh and calf are usually the result of great saphenous vein (GSV) incompetence. To minimize the chance for recurrence, the incompetent GSV must be eliminated from the circulation. This concept has been substantiated in several prospective randomized clinical trials involving patients who were treated with or without saphenectomy by conventional vein stripping.2–5 The recurrence rates for limbs without saphenectomy were much higher than those for limbs with saphenectomy. Of course, now thermal ablation techniques with either radiofrequency or laser have proved to be the methods of choice for eliminating the GSV from the circulation.6,7

In cases where no “feeding source” is found, phlebectomy of the varicosities may be all that is required. Labropoulos et al.8 have shown that varicose veins may result from a primary vein wall defect and that reflux may be confined to superficial tributaries throughout the lower limb. Without great and small saphenous trunk incompetence, perforator and deep vein incompetence, or proximal obstruction, their data suggest that reflux can develop in any vein without an apparent feeding source. This is often the case when bulging reticular veins are seen along the course of the lateral leg. This lateral subdermic complex and its vein of Albanese are often dilated and bulging in elderly patients. The underlying source of venous hypertension is usually perigeniculate perforating veins, not easily identifiable with duplex imaging. AP using an 18-gauge needle stab incision and a small crochet hook for exteriorization of the vein is an excellent procedure for this clinical problem.

Imaging

We prefer mapping these veins using visual inspection and palpation; other investigators might prefer transillumination mapping using specialized vein lights.9 Ultrasound-guided vein hooking is useful for deeper veins.

Hemostasis and Anticoagulation

Klein10 has shown through clinical studies that a dose of 35 mg/kg of dilute lidocaine solution is well tolerated and safe. Infiltrating solutions should contain epinephrine in appropriate concentrations to induce vasoconstriction and more gradual absorption of lidocaine into the bloodstream.

Infections are rare after liposuction and venous procedures with tumescent anesthesia and are usually confined to the incision site.11 The reason for the low rate of infection is not clear, although there are reports of lidocaine concentration–dependent bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity. Pathogens commonly found on the skin may be sensitive to this activity.12

Operative Steps

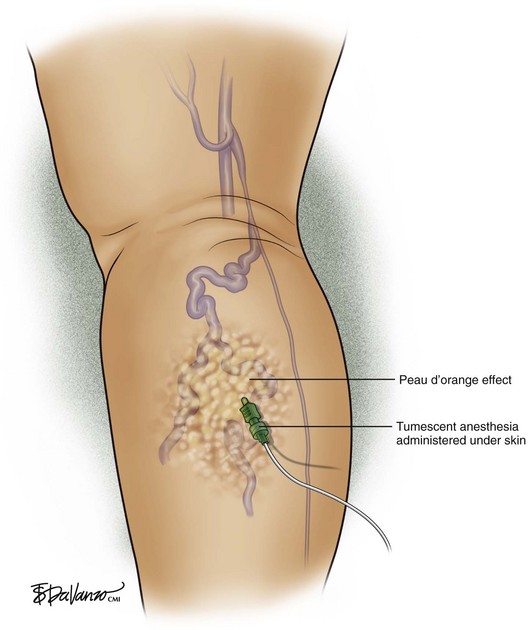

Tumescent anesthesia (Fig. 9-1): Tumescent anesthesia allows large areas of the body to be anesthetized with minimal effect on intravascular fluid status, avoidance of general anesthesia, and short postoperative recovery. Tumescent anesthesia provides a safe, easy-to-administer technique for use with AP. The technique of tumescent anesthesia involves infiltration of the subdermal compartment with generous volumes of a 0.1% solution of lidocaine with epinephrine. The anesthetic preparation is administered subdermally under pressure. The doctor pushes the fluid until a characteristic peau-d’orange effect is visualized on the skin. The tumescent fluid hydrodissects the subcutaneous fat from the venous tissue as it enters, thus facilitating vein extraction afterward.

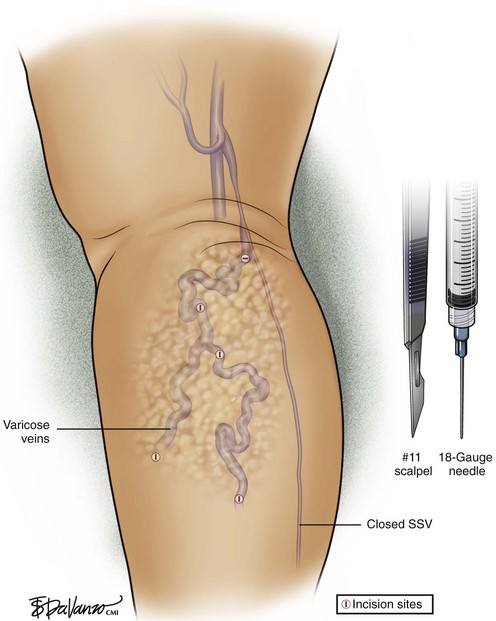

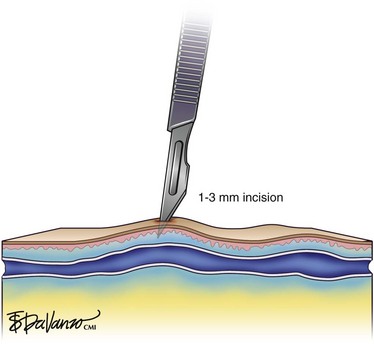

Incisions (Figs. 9-2 and 9-3): The most popular instruments for creating incisions are No. 11 scalpel blades, 18-gauge needles, and 15-degree ophthalmologic Beaver blades. Incision length should correspond to vein size but is usually in the range of 1 to 3 mm. The author removes small varicose veins through an 18-gauge needle hole, while larger veins require slightly larger incisions made with a No. 11 scalpel blade.

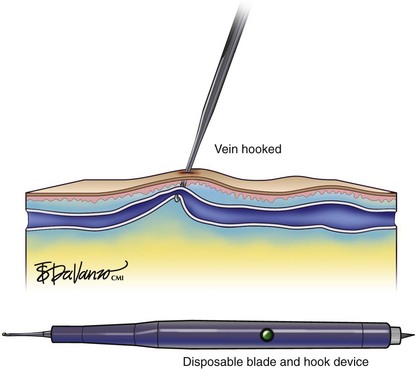

Hooking and extraction (Fig. 9-4): Hooking the target vein through the small incision is the next step. There are multiple instruments available—some are medical and others are manufactured for crochet. The latest available device is disposable and mounts the blade and hook on the same instrument.

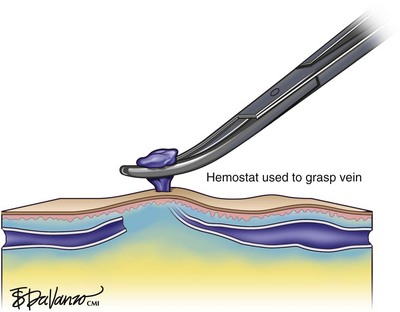

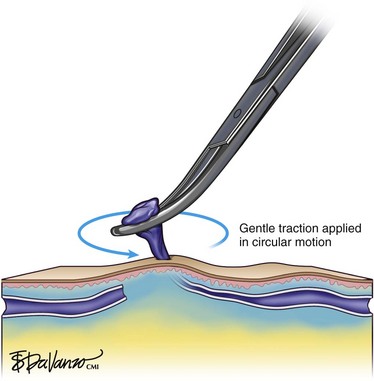

Using a hook of choice, the vein is exteriorized from the wound. Hooks need not be introduced into the wound deeper than 2 to 3 mm, and they should be inserted gently and deliberately to avoid unnecessary trauma to the wound margins. Gentle probing and “searching” for the target vein with the hook are routinely necessary and should be done with great care. Once a segment of vein is exteriorized from the wound, it is grasped with fine hemostatic clamps (Fig. 9-5). With the use of gentle traction in a circular motion, the vein is teased out of the wound (Fig. 9-6).

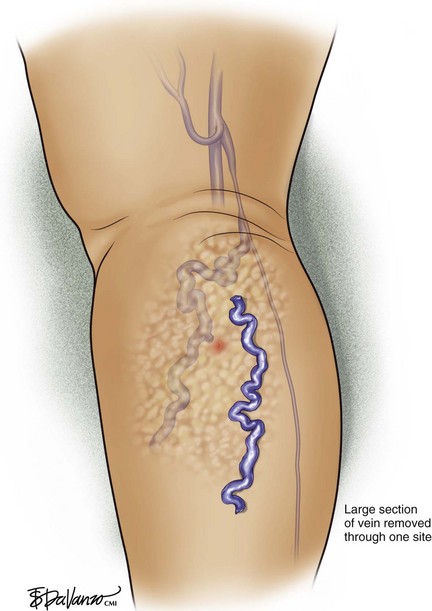

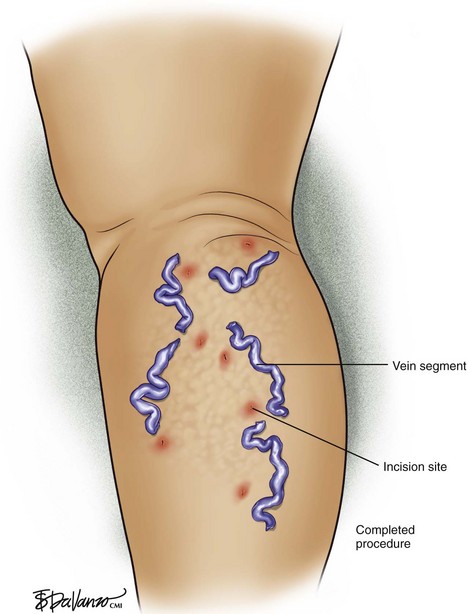

When traction is applied to the vein, the skin juxtaposed to the incision site will momentarily depress downward. Attention to this detail gives the operator an idea of where to place the next incision. The depression represents the point at which the vein will avulse. The next incision is made near the area of depressed skin, and the process is repeated sequentially until all of the venous bulges have been addressed. Although all bulges should be marked preoperatively, not all of the marks need to be incised if the operator takes care in identifying the skin depressions described earlier. It is very rewarding when a large segment is removed from a single site (Fig. 9-7). On balance, in some cases only small fragments of varicose veins are encountered that can make the operation quite tedious; this frequently cannot be avoided.

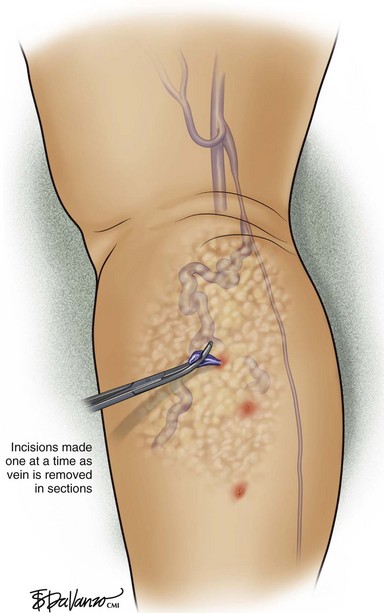

If vein exteriorization proves difficult, it is better to make larger incisions rather than induce ischemia at the wound edges from excessive stretching. For the number of incisions to be reduced, the incisions should be made one at a time (Fig. 9-8). If avulsion proves difficult and the vein breaks, it is more convenient to make more incisions than to waste time trying to retrieve more vein from the same incision (Fig. 9-9).

A single suture to close wounds near the foot and ankle may be required because of the elevated venous pressure at these locations in the upright position. Frequent ambulation will aid in decreasing ambulatory venous pressure in these dependent locations. Adhesive tapes are associated with a high incidence of skin blistering; therefore, these must be used with caution.13

Pearls and Pitfalls

The saphenous and sural nerves are particularly prone to injury below the knee because of their proximity to the GSV and SSV. If the saphenous or sural nerves are displaced by the hook, the patient will usually complain of shooting pain into the foot. This is a sign for the surgeon to gently release the structure and replace it in situ. Occasionally, hair-sized sensory cutaneous nerves are encountered and inadvertently avulsed during the course of AP. Patients will experience sharp pain that usually dissipates after 2 to 5 minutes without treatment. If this occurs in the ankle and foot area, chances are that the patient will develop postoperative paresthesias or areas of dysesthesia that in most cases will be temporary.14

Eyelid: AP of the periocular vein avoids the concerns regarding thrombotic phenomena within ocular, orbital, or cerebral veins possibly associated with periocular vein sclerotherapy. Weiss and Ramelet15 reported excellent results on 10 patients who underwent removal of periocular reticular blue veins via AP. A single puncture with an 18-gauge needle sufficed in most cases. It is important to attempt to remove the entire segment, as partial resection may lead to recurrence. The use of postoperative compression for 10 minutes reduces the incidence of bruising. The puncture sites typically disappear quickly without scarring.

Complications

Complications from AP in experienced hands are rare and, when they do occur, are minor.16 A multicenter study performed in France evaluated 36,000 phlebectomies. The most frequently encountered complications were telangiectasias (1.5%), blister formation (1%), phlebitis (0.05%), hyperpigmentation (0.03%), postoperative bleeding (0.03%), temporary nerve damage (0.05%), and permanent nerve damage (0.02%).

Comparative Effectiveness of Existing Treatments

It is important to note that Monahan reported during the follow-up period that complete resolution of visible varicose veins was seen in only 13% of limbs after saphenous ablation alone.17 Therefore, about 90% of patients require another intervention after saphenous ablation to fully eradicate their visible varicose veins. This has also been our experience.

AP versus TriVex: In a published prospective comparative randomized trial comparing AP with the new technique of transillumination powered phlebectomy (TriVex), there was no difference in operating time. Although an incision ratio of 7 : 1 favored TriVex, there was no perceived cosmetic benefit between the patient groups. There was a higher number of recurrences in the TriVex group (21.2%) compared with the AP group (6.2%) at 52 weeks postoperatively. Assessment of pain scores showed no difference between groups.18

AP versus compression sclerotherapy: There is one randomized controlled trial on recurrence rates and other complications after sclerotherapy and AP. One year after sclerotherapy, 25% of varicose veins had recurred versus only 2% recurrence after phlebectomy. After 2 years, the difference in recurrence was even larger: 38% recurrence in the sclerotherapy group and only 2% in the AP group.19

Conclusion

AP is elegant by its mere simplicity. It is effective and safe with acceptable cosmetic results (Fig. 9-10). AP is a perfect complement to endovenous thermal ablation of the saphenous veins. With this combination, patients can expect all varicose veins to vanish following a 1-hour procedure that used only local anesthesia in the comfort of a physician’s office.

1 Muller R. Traitement des varices par la phlebectomie ambulatoire. Phlebologie. 1966;19:277-279.

2 Jones L, Braithwaite BD, Selwyn D, et al. Neovascularisation is the principal cause of varicose vein recurrence: results of a randomized trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:442-445.

3 Winterborn RJ, Foy C, Earnshaw JJ. Causes of varicose vein recurrence: late results of a randomized controlled trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:634-639.

4 Dwerryhouse S, Davies B, Harradine K, et al. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins: five-year results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:589-592.

5 Sarin S, Scurr JH, Coleridge Smith PD. Stripping of the long saphenous vein in the treatment of primary varicose veins. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1455-1458.

6 Min RJ, Khilnani N, Zimmet SE. Endovenous laser treatment of saphenous vein reflux: long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:991-996.

7 Merchant RF, Pichot O, Myers KA. Four-year follow-up on endovascular radiofrequency obliteration of great saphenous reflux. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:129-134.

8 Labropoulos N, Kang SS, Mansour MA, et al. Primary superficial vein reflux with competent saphenous trunk. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:201-206.

9 Weiss RA, Goldman MP. Transillumination mapping prior to ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:447-450.

10 Klein JA. Tumescent technique for local anaesthesia improves safety in large-volume liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1085-1098.

11 Keel D, Goldman MP. Tumescent anaesthesia in ambulatory phlebectomy: addition of epinephrine. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:371-372.

12 Schmid RM, Rosenkranz HS. Antimicrobial activity of local anaesthetics: lidocaine and procaine. J Infect Dis. 1970;121:597.

13 Almeida JI, Raines JK. Principles of ambulatory phlebectomy. In: Bergan JJ, editor. The Vein Book. San Diego: Elsevier; 2007:247-256.

14 Ramelet AA. Complications of ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:947-954.

15 Weiss RA, Ramelet AA. Removal of blue periocular lower eyelid veins by ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:43-45.

16 Olivencia JA. Complications of ambulatory phlebectomy: review of 1,000 consecutive cases. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:51-54.

17 Monahan DL. Can phlebectomy be deferred in the treatment of varicose veins? J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:1145-1149.

18 Aremu MA, Mahendran B, Butcher W, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial: conventional versus powered phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:88-94.

19 De Roos KP, Nieman FH, Neumann HA. Ambulatory phlebectomy versus compression sclerotherapy: results of a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:221-226.