Alterations in collagen and elastin

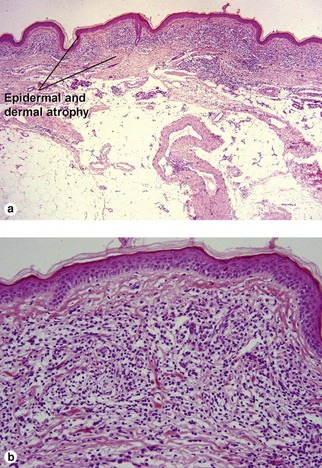

Lichen sclerosus (et atrophicus)

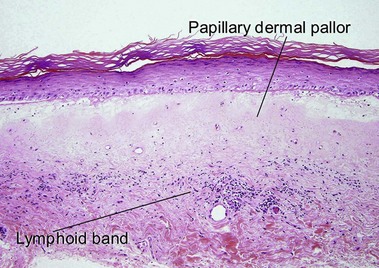

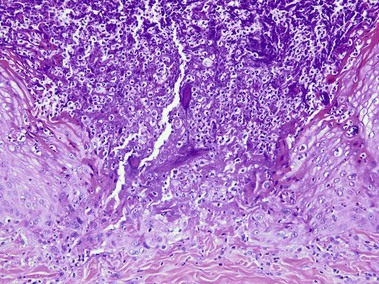

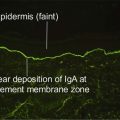

Lichen sclerosus may involve skin or mucosa. Follicular plugging is common, and the plugs may resemble comedones clinically. The epidermis is commonly atrophic and the rete pattern is commonly effaced; however, scratching may produce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, especially in vulvar lesions. Squamous cell carcinoma rarely develops in long-standing genital lesions of lichen sclerosus and must be distinguished from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Papillary dermal edema may produce a subepidermal bulla. Vacuolar interface dermatitis and pigment incontinence are common. Epidermotropic lymphocytes may be hyperchromatic and may mimic mycosis fungoides (Table 13.1). The differential diagnosis also includes radiation dermatitis and morphea.

Table 13-1

Features of lichen sclerosus and chronic radiation dermatitis

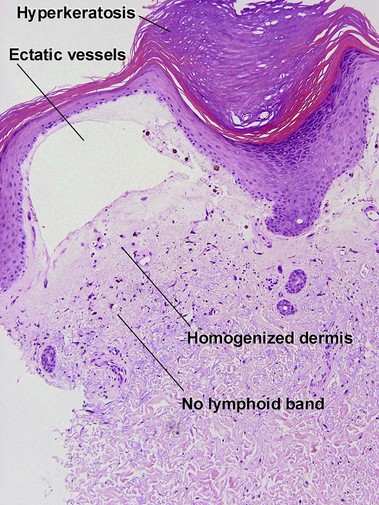

| Feature | Lichen sclerosus | Chronic radiation dermatitis |

| Compact red stratum corneum | Yes | Yes |

| Superficial dermal pallor | Yes | Yes |

| Epidermal atrophy | Variable | Variable |

| Follicular plugging | Common | Rare |

| Vacuolar interface dermatitis | Yes | No |

| Lymphoid band | Yes | No |

| Pigment incontinence | Common | Usually absent |

| Superficial dermal vessels | Normal to slight dilatation | Widely ectatic |

| Radiation elastosis | No | Yes |

| Adnexal structures | Present | Absent |

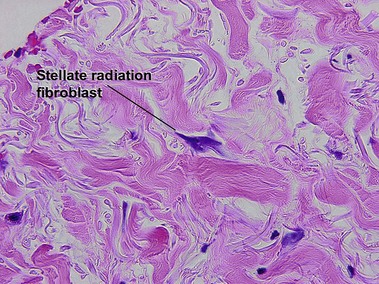

| Large stellate fibroblasts | No | Yes |

| Deep dermis | Normal | Sclerotic |

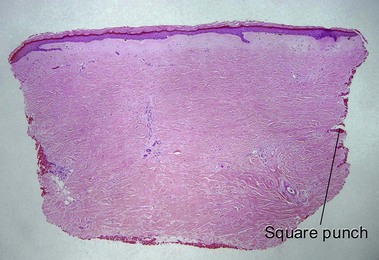

| Shape of punch biopsy | Tapered | Square |

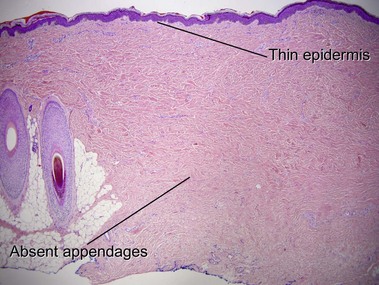

Chronic radiation dermatitis

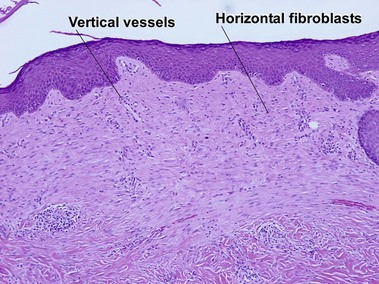

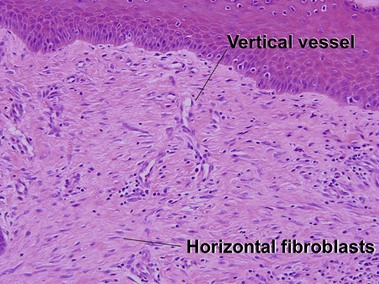

There is typically hyperkeratosis and epidermal atrophy with effaced rete that may alternate with hyperplasia. Stellate cells with large nuclei are usually present (radiation fibroblasts). The eccrine glands are atrophic and the pilosebaceous structures are absent; however, the arrector pili muscle may survive. The dermal collagen is hyalinized. Radiation elastosis may resemble solar elastosis but extends into follicular fibrous tracts. The superficial blood vessels are dilated, whereas the deeper vessels have thick walls.

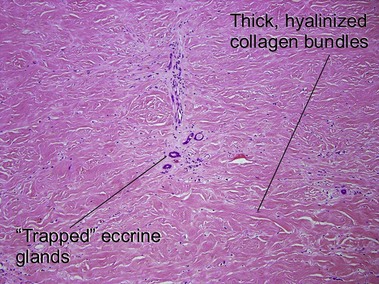

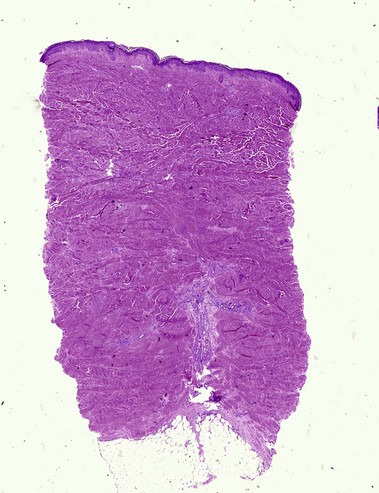

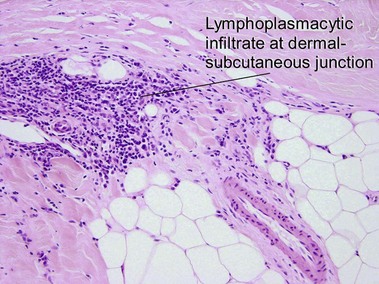

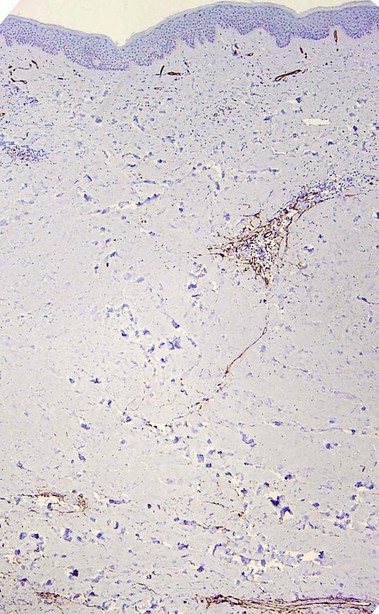

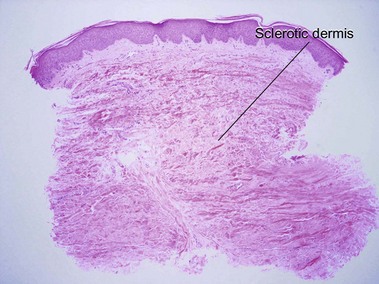

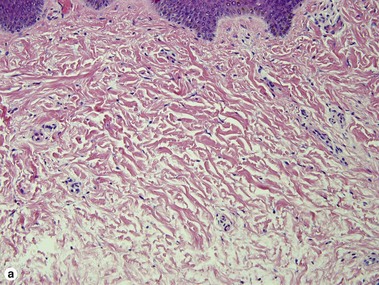

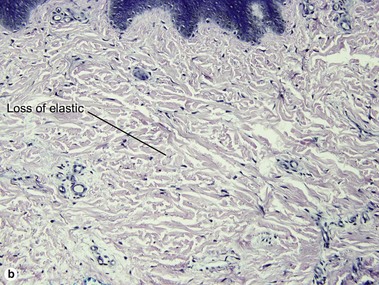

Morphea/scleroderma

Scleroderma encompasses a group of diseases. Localized cutaneous disease may present as morphea or linear scleroderma (including en coup de sabre). In addition to cutaneous lesions, Raynaud’s phenomenon and variable organ involvement characterize diffuse systemic scleroderma and limited systemic scleroderma (CREST). Although the histologic features are similar, morphea is usually more inflammatory and lacks the intimal thickening and luminal obliteration of vessels seen in systemic scleroderma.

Sclerodermoid graft-versus-host disease

Dermal sclerosis begins in the papillary dermis and may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. In the chronic phase of GvHD, an early lichenoid stage and a later sclerotic stage can be distinguished. Each stage can occur without the other. Unlike radiation dermatitis, vascular ectasia and radiation fibroblasts are not identified. Clinically, the skin often has a corrugated appearance.

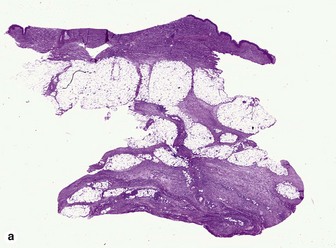

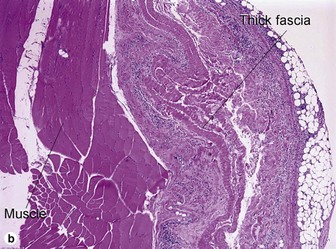

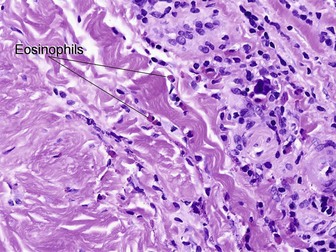

Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman’s syndrome)

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a scleroderma-like disorder of the fascia that can be distinguished by the sudden onset of painful edema and progressive induration, typically involving an extremity or extremities following strenuous exercise. The condition is named for its association with peripheral eosinophilia. Eosinophils may be found in the tissue but are not required, and are typically absent. The fibrosis and hyalinization involve the fascia and deep subcutaneous septa. In many cases, the overlying adipose tissue shows no significant changes. A deep incisional biopsy to include fascia is required for diagnosis.

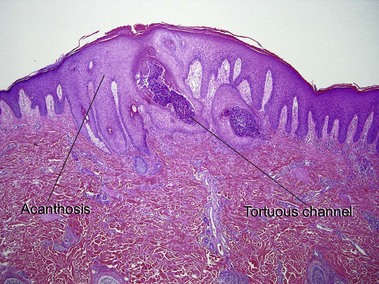

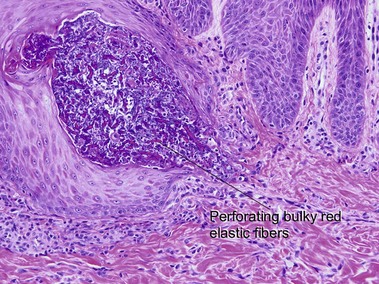

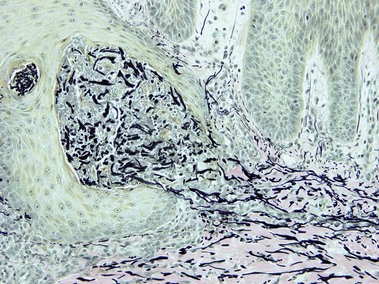

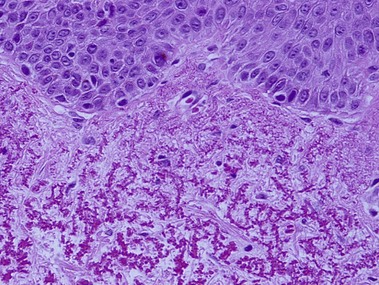

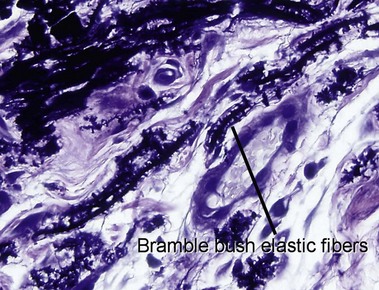

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa

The papules of elastosis perforans serpiginosa coalesce in an arcuate or serpiginous pattern, most commonly on the neck, face, or upper extremity. Elastic tissue stains reveal increased abnormal, thickened elastic fibers in the dermis in the vicinity of the channel.

Reactive perforating collagenosis

The primary lesion is a small papule with a hyperkeratotic central umbilication. Classic, true reactive perforating collagenosis is an inherited genodermatosis, most often in an autosomal-dominant pattern. These lesions occur in children and are precipitated by minor trauma.

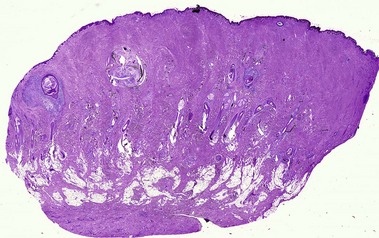

Scar and keloid

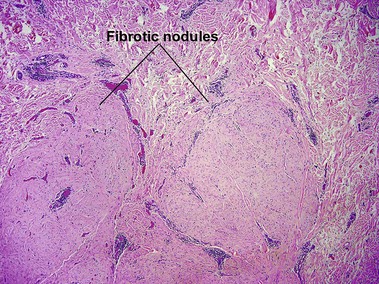

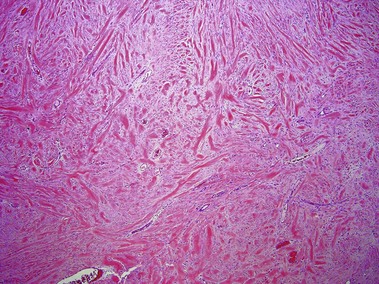

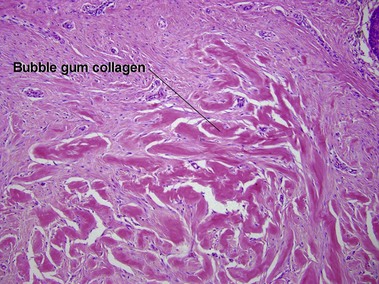

Keloid

Keloids clinically differ from hypertrophic scars by extending beyond the confines of the original wound. Elastic fibers and adnexal structures are diminished or absent in both scars and keloids. Recent surgical scars may also contain signs of Monsel’s solution, gelfoam, or aluminum chloride.

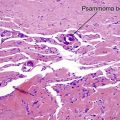

Acne keloidalis nuchae

The plasma cell infiltrate is related to the predominance on the posterior neck. Plasma cells are typically a component of the inflammatory infiltrate on the face, occipital scalp/posterior neck, axillae, breast, genital area, and shins. Hair shafts free in the dermis are surrounded by microabscesses and/or giant cells.

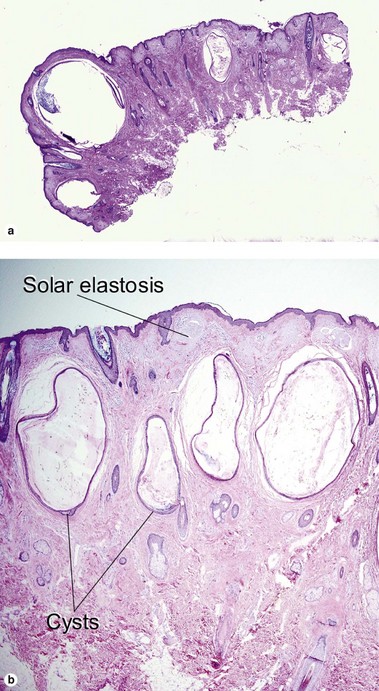

Favre–Racouchot syndrome (nodular elastosis with cysts and comedones)

This solar degeneration condition presents with yellowish plaques lateral to the eyes that are studded with cysts and multiple open comedones. Smoking may act in conjunction with the solar damage to create this syndrome. Solar elastosis is a bluish, amorphous material that is primarily sun-damaged elastic and/or collagen fibers.

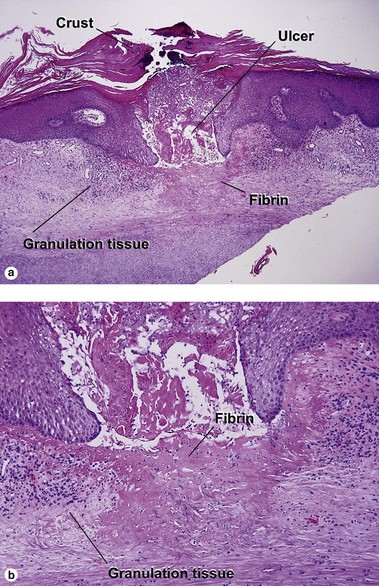

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis

Depending on the depth of the biopsy, cartilage may be present but is not required for diagnosis. Collagen degeneration occurs from a combination of pressure, poor vascularity, and solar damage (see Chapter 15).

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

Borrelial spirochetes may be found with silver stains. This is a late manifestation of infection by Borrelia. It is most frequently reported in Europe, where B. afzelii is endemic.

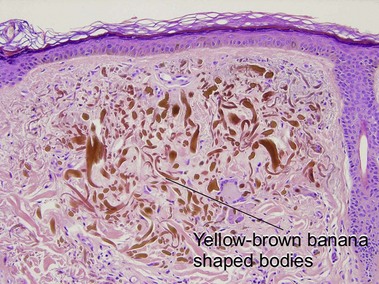

Ochronosis

The inherited form, also known as alkaptonuria, is an autosomal-recessive disorder due to homogentisic acid oxidase deficiency. Exogenous ochronosis occurs as a result of application of hydroquinone or contact with phenol (carbolic acid).

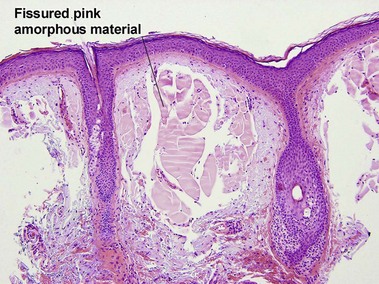

Colloid milium

The adult type develops in the setting of severe sun damage, on the face, neck, and dorsal hands. This material represents the final product of severe solar degeneration but can stain weakly with amyloid stains (crystal violet, Congo red, thioflavin T). However, it fails to react with pagoda red. The juvenile form develops on the head and neck before the development of sun damage. This type is Congo red-negative but positive with antikeratin antibodies confirming the origin of the material from degenerated keratinocytes.

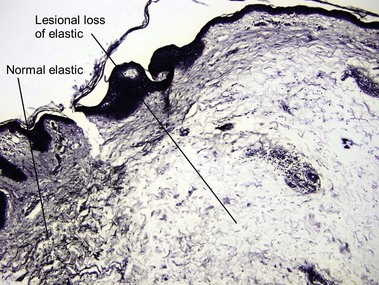

Anetoderma

These oval lesions have an atrophic or wrinkled surface and bulge outward or are slightly depressed and herniate inward with pressure. The upper trunk and upper arms of young adults are typically affected. Primary lesions have been reported with (Jadassohn–Pellizzari type) and without (Schweninger–Buzzi type) a preceding inflammatory stage. Clinically inflamed lesions may have a perivascular and sometimes interstitial infiltrate but established lesions look like normal skin on H&E-stained sections and reveal minimal to no elastic fibers with special stains. Secondary anetoderma can occur from various processes including syphilis, other infectious processes, granulomatous diseases, lupus, and lymphoma.

Connective tissue nevus

Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of the extracellular connective tissue, whether it is collagen, elastic, or glycosaminoglycans, that is present in abnormal amounts. Collagenomas can be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern or associated with Proteus syndrome and tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches). They present as skin-colored papules, nodules or plaques. Elastomas are associated with Buschke–Ollendorff syndrome.

Aplasia cutis congenita

Aplasia cutis is due to congenital absence of skin. It may present as an ulceration, membranous lesion, or atrophic scarring, most commonly on the vertex of the scalp. It may be associated with limb defects (Adams–Oliver syndrome), mental retardation, epidermal nevi, epidermolysis bullosa (Bart syndrome), chromosomal abnormalities, fetus papyraceus, or focal dermal hypoplasia.

Aberer, E, Klade, H, Hobisch, G. A clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical comparison of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and morphea. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991; 13(4):334–341.

Aiba, S, Tabata, N, Ohtani, H, et al. CD34+ spindle-shaped cells selectively disappear from the skin lesion of scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 1994; 130(5):593–597.

Blackburn, WR, Cosman, B. Histologic basis of keloid and hypertrophic scar differentiation. Clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Pathol. 1966; 82(1):65–71.

Choi, YJ, Lee, SJ, Choi, CW, et al. Multiple unilateral zosteriform connective tissue nevi on the trunk. Ann Dermatol. 2011; 23(Suppl 2):S243–S246.

de Feraudy, S, Fletcher, CD. Fibroblastic connective tissue nevus: a rare cutaneous lesion analyzed in a series of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012; 36(10):1509–1515.

Fretzin, DF, Beal, DW, Jao, W. Light and ultrastructural study of reactive perforating collagenosis. Arch Dermatol. 1980; 116(9):1054–1058.

Gebhart, W, Bardach, H. The “lumpy-bumpy” elastic fiber. A marker for long-term administration of penicillamine. Am J Dermatopathol. 1981; 3(1):33–39.

Graham, JH, Marques, AS. Colloid milium: a histochemical study. J Invest Dermatol. 1967; 49(5):497–507.

Handfield-Jones, SE, Atherton, DJ, Black, MM, et al. Juvenile colloid milium: clinical, histological and ultrastructural features. J Cutan Pathol. 1992; 19(5):434–438.

Rahbari, H. Histochemical differentiation of localized morphea-scleroderma and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 1989; 16(6):342–347.

Uitto, J, Santa Cruz, DJ, Bauer, EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980; 3(3):271–279.

Wienecke, R, Schlupen, EM, Zochling, N, et al. Staining of amyloid with cotton dyes. Arch Dermatol. 1984; 120(9):1184–1185.