Alphabetical list of conditions

Achondroplasia

Axial skeleton

1. Decreasing interpedicular distance caudally in the lumbar spine.

2. Short pedicles with a narrow sagittal diameter of the lumbar spinal canal.

4. Anterior vertebral body beak at T12/L1/L2 associated with gibbous deformity once sitting. Gibbous may reverse and develop into hyperlordosis of lumbar spine once walking.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

A Chest

CXR and CT changes rarely provide definitive diagnosis.

Opportunistic infections

1. Pneumocystis jiroveci – most common opportunistic (fungal) infection. Associated with CD4+ count < 200 cells/µl. With effective chemoprophylaxis and antiretroviral treatment, incidence has fallen. Chest radiographs may be normal at presentation but typically progresses to show bilateral perihilar or diffuse ground-glass opacification and reticulation. Without treatment, there is rapid progression to air-space opacification. Diffuse ground-glass opacification, thickened interlobular septa and consolidation are the key findings on HRCT. Thin-walled cysts are present in ~30%. Less common imaging features include:

(a) Asymmetrical upper lobe disease – in patients on prophylactic therapy; may be confused with tuberculosis.

2. Mycobacterium tuberculosis – an important infection in HIV-positive patients, and diagnosis is difficult. Imaging features depend on severity of immune compromise: depressed but near-normal CD4+ levels are associated with similar radiological features to non-immunocompromised patients (upper lobe nodules ± cavitation). With more severe depression, more atypical patterns (non-upper lobe predilection; lower propensity for cavitation) and disseminated infection are likely.

Neoplasms

1. Kaposi’s sarcoma – decreasing incidence with advent of HAART. Lung involvement is less common than cutaneous and/or visceral disease. Perihilar bronchocentric nodules/masses are the typical radiological findings – ‘flame-shaped’ opacities may be seen on CT.

2. Pulmonary lymphoma – increasingly common: non-Hodgkin’s more common than Hodgkin’s.

Other parenchymal lung diseases

1. Non-specific interstitial pneumonia – variable prevalence. Clinical presentation and radiological features may mirror those seen in patients with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) but CD4+ counts tend to be higher in patients with NSIP.

2. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia – most common in children and associated with EBV infection. Non-specific radiological appearances (ground-glass opacities, small nodules, bronchiectasis.

3. Obliterative bronchiolitis – in adolescents with vertically transmitted infection.

B Abdomen

Infections

1. Primary HIV – oesophageal ulceration.

2. Candida – usually oropharynx and oesophagus. AIDS defining. Mucosal plaques, fold thickening, ‘shaggy’ oesophagus on barium swallow.

3. Herpes – small discrete ulcers on barium swallow.

4. CMV – most common gastrointestinal infection. Can occur anywhere but usually lower gastrointestinal tract. Oesophagus – large mid-oesophageal ulcer; CMV gastritis, enteritis and colitis – superficial progressing to deep ulceration (mimic Crohn’s), extensive bowel wall thickening on CT, US; segmental or diffuse, lymphadenopathy not prominent.

5. TB – ileocaecal jejunoileum most common sites (upper gastrointestinal tract less common). Segmental ulcers, wall thickening, strictures, and mass-like lesions of the caecum and terminal ileum. Regional low-attenuation necrotic lymphadenopathy. Hepatosplenomegaly (occasional focal lesions).

6. Chlamydia trachomatis – causes lymphogranuloma venereum. Generally in men who have sex with men as a HIV coinfection. Introduced anally and causes a proctocolitis. May have inguinal lymphadenopathy and collections.

7. Mycobacterium avium complex – usually small bowel. Mimics Whipple’s (irregular fold thickening and mild dilatation). Prominent lymphadenopathy. Hepatosplenomegaly (occasional focal lesions).

8. Cryptosporidium – diffuse fold thickening, flocculation of barium (mimics sprue). No lymphadenopathy.

9. Rochalimaea henselae (peliosis hepatis) – fever, sweats, right upper quadrant pain. Sonographically liver inhomogeneous, with hyperechoic and hypoechoic regions. Cavities may be visible on CT (if large).

10. PCP – liver/spleen/kidneys – hypoechoic/hypoattenuating masses or multiple tiny echogenic/hyperattenuating foci (calcified).

Malignancy

1. Kaposi’s sarcoma – CD4 count typically < 200

(a) Liver/spleen – multifocal hyperechoic nodules (5–12 mm) adjacent to portal veins on US scan. CT – hypoattenuating nodules, with delayed enhancement (mimic haemangiomas).

(b) Gastrointestinal tract – usually with cutaneous involvement. Anywhere in gastrointestinal tract but duodenum most common. Submucosal masses (0.5–3 cm) ± ulceration at CT/barium. Hyperattenuating lymphadenopathy.

2. Lymphoma – usually aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Peripheral nodes are present in 50% and extranodal involvement is common, particularly bowel, viscera and marrow.

Common symptoms/signs

1. Dysphagia – common. Usually due to candidiasis, but occasionally caused by viral oesophagitis or Kaposi’s sarcoma.

2. Hepatosplenomegaly – non-specific. Seen in many infections (CMV, TB, MAI) and lymphoma.

3. Diarrhoea – common. Usually CMV colitis if mild, or Cryptosporidium (protozoa) if severe. Giardia, Clostridium difficile and Mycobacterium may also occur.

4. Retroperitoneal/mesenteric lymphadenopathy

(a) Progressive generalized lymphadenopathy syndrome – i.e. two or more extrainguinal nodes persisting for > 3 months with no obvious cause. Biopsy reveals benign hyperplasia, and CT shows clusters of small nodes < 1 cm in diameter in the mesentery and retroperitoneum.

5. AIDS cholangiopathy – right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting and fever. Due to infection by CMV or Cryptosporidium. Gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct strictures, diverticula, intraluminal filling defects and strictures of the juxta-ampullary pancreatic duct.

6. HIV nephropathy – proteinuria and rapidly progressive renal failure. Usually, globally enlarged kidneys.

Boiselle, P. M., Crans, S. A., Jr., Kaplan, M. A. The changing face of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in AIDS patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 172:1301–1309.

Burns, J., Shaknovich, R., Lau, J., et al. Oncogenic viruses in AIDS: mechanisms of disease and intrathoracic manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 189:1082–1087.

Ferrand, R. A., Desai, S. R., Hopkins, C., et al. Chronic lung disease in adolescents with delayed diagnosis of vertically-acquired HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:145–152.

Guihot, A., Couderc, L. J., Rivaud, E., et al. Thoracic radiographic and CT findings of multicentric Castleman disease in HIV-infected patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2007; 22:207–211.

Kuhlman, J. E. Imaging pulmonary disease in AIDS: state of the art. Eur Radiol. 1999; 9:395–408.

Logan, P. M., Finnegan, M. M. Pictorial review: pulmonary complications in AIDS: CT appearances. Clin Radiol. 1998; 53:567–573.

Major, N. M., Tehranzadeh, J. Musculoskeletal manifestations of AIDS. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997; 35:1167–1190.

Provenzale, J. M., Jinkins, J. R. Brain and spine imaging findings in AIDS patients. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997; 35:1127–1166.

Redvanly, R. D., Silverstein, J. E. Intra-abdominal manifestations of AIDS. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997; 35:1083–1126.

Reeders, J. W., Goodman, P. C., 2001. Radiology of AIDS. Springer, Heidelberg.

Reeders, J. W., Yee, J., Gore, R. M., et al. Gastrointestinal infection in the immunocompromised (AIDS) patient. Eur Radiol. 2004; 14(Suppl 3):E84–E102.

Restrepo, C., Lemos, D., Gordillo, H. Imaging findings in musculoskeletal complications of AIDS. Radiographics. 2004; 24:1029–1049.

Restrepo, C. S., Ocazionez, D. Kaposi’s sarcoma: imaging overview. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011; 32(5):456–469.

Richards, P. J., Armstrong, P., Parkin, J. M., et al. Chest imaging in AIDS. Clin Radiol. 1998; 53:554–566.

Spencer, S. P., Power, N., Reznek, R. H. Multidetector computed tomography of the acute abdomen in the immunocompromised host: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009; 38(4):145–155.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in children

AIDS in children differs from AIDS in adults in the following ways:

2. Children are more likely to have serious bacterial infections or CMV.

3. They develop pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia (PLH)/lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), which is rare in adults.

4. They almost never develop Kaposi’s sarcoma.

5. They are less likely to be infected with Toxoplasma, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Cryptococcus and Histoplasma.

6. Two patterns of presentation and progression can be recognized:

(a) In the first year of life with serious infections and encephalopathy. Poor prognosis.

(b) Preschool and school age with bacterial infections and lymphoid tissue hyperplasia. Survival is longer, to adolescence.

Prognostic factors are severity of disease in the mother, age of onset and severity at onset.

Chest

1. PCP – may be localized initially but typically there is rapid progression to generalized lung shadowing, which is a mixed alveolar and interstitial infiltrate. 50% of infections occur at age 3–6 months. Two-thirds of infections are the first and only infective episode.

3. LIP/PLH – in 50% of patients. Insidious onset of clinical symptoms. CXR shows a diffuse, symmetrical reticulonodular or nodular pattern (2–3 mm in diameter) which is most easily seen at the bases and periphery of the lungs ± hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The nodules consist of collections of lymphocytes and plasma cells without any organisms. Children with LIP are more likely to have generalized lymphadenopathy, salivary gland enlargement (particularly parotid) and finger clubbing than those with CXR changes due to opportunistic infection, and the prognosis for LIP is better. Long-standing LIP may be complicated by lower lobe bronchiectasis or cystic lung disease (resembling that seen in histiocytosis).

4. Mediastinal or hilar adenopathy may be secondary to PLH, M. tuberculosis, MAI, CMV, lymphoma or fungal infection.

5. Cardiomyopathy, dysrhythmias and unexpected cardiac arrest.

Abdomen

1. Hepatosplenomegaly – due to chronic active hepatitis, hepatitis A or B, CMV, EBV and M. tuberculosis, generalized sepsis, tumour (fibrosarcoma of the liver) or congestive cardiac failure.

2. Oesophagitis – Candida, CMV or herpes simplex.

3. Chronic diarrhoea – in 40–60% of children. Infectious agents are only infrequently found but include Candida, CMV and Cryptosporidium. Radiological findings are non-specific and include a malabsorption-type pattern with thickening of bowel wall and mucosal folds and dilatation. Fine ulceration may be seen.

5. Mesenteric, para-aortic and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy – due to MAI, lymphocytic proliferation (lymph-node syndrome), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma (rare in childhood).

6. HIV nephropathy – children may present with proteinuria, fluid and electrolyte imbalances and/or acute or chronic renal failure. US shows enlarged echogenic kidneys and CT shows enlarged pyramids. Simple cysts may be present.

7. UTI – in up to 50% of AIDS patients. May be due to common organisms or unusual agents, e.g. CMV, Cryptococcus, Candida, Aspergillus, Mycobacterium and Pneumocystis.

Head

1. HIV encephalopathy is divided into two types:

(a) Progressive encephalopathy comparable to adult AIDS dementia complex. There is step-wise deterioration of mental status and higher functions. It is associated with severe immune deficiency.

(b) Static encephalopathy, associated with better higher functions but failure to reach appropriate milestones.

(a) Cerebral atrophy – worse with progressive encephalopathy.

(b) Non-enhancing white matter of ↓ attenuation (CT) or ↑ T2W signal (MRI) in the frontal lobes, periventricular regions and centrum semiovale.

2. Intracranial calcifications – in up to 33% of HIV-infected children. Usually bilateral and symmetrical and most commonly seen in the globus pallidus and putamen; less commonly in the subcortical frontal white matter and cerebellum. Usually not seen before 10 months of age; early calcifications are more likely because of congenital infections.

3. Malignancy – most commonly high-grade B-cell lymphoma associated with EBV infection.

(a) Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy – difficult to distinguish from HIV encephalopathy, but tends to be more focal, asymmetrical and commoner in the posterior parietal lobe.

(b) Toxoplasmosis – enhancing mass lesions with surrounding oedema in the basal ganglia and corticomedullary junction of the periventricular white matter.

(c) Meningitis – due to fungi, Mycobacteria spp. and Nocardia, in addition to the more usual causes of meningitis.

Haller, J. O. AIDS-related malignancies in pediatrics. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997; 35(6):1517–1538.

Haller, J. O., Cohen, H. L. Pediatric HIV infection: an imaging update. Pediatr Radiol. 1994; 24:224–230.

Martinoli, C., Pretolesi, F., Del Bono, V., et al. Benign lymphoepithelial parotid lesions in HIV-positive patients: spectrum of findings at gray-scale and Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995; 165(4):975–979.

Miller, C. R. Pediatric aspects of AIDS. Radiol Clin North Am. 1997; 35:1191–1222.

Safriel, Y. I., Haller, J. O., Lefton, D. R., et al. Imaging of the brain in the HIV-positive child. Pediatr Radiol. 2000; 30:725–732.

Stoane, J. M., Haller, J. O., Orentlicher, R. J. The gastrointestinal manifestations of pediatric AIDS. Radiol Clin North Am. 1996; 34(4):779–790.

Zinn, H. L., Haller, J. O. Renal manifestations of AIDS in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1999; 29:558–561.

Acromegaly

The effect of excessive growth hormone on the mature skeleton.

Appendicular skeleton

1. Increased width of bones but unaltered cortical thickness.

2. Tufting of the terminal phalanges, giving an ‘arrowhead’ appearance.

3. Prominent muscle attachments.

4. Widened joint spaces – especially the metacarpophalangeal joints: due to cartilage hypertrophy.

6. Increased heel pad thickness (> 21.5 mm in female; > 23 mm in male).

Alkaptonuria

Aneurysmal bone cyst

1. Age – 10–30 years (75% occur before epiphyseal closure).

2. Sites – ends of long bones (70–80%), especially in the lower limbs. Also flat bones and vertebral appendages.

(a) Arises in unfused metaphysis or in metaphysis and epiphysis after fusion.

(b) Well-defined lucency with thin but intact cortex.

(c) Marked expansion (ballooning).

(d) Thin internal strands of bone/trabeculation.

(e) ± New bone in the angle between original cortex and the expanded part.

(f) Fluid–fluid level(s) on CT and MRI.

(g) In the spine they involve the posterior elements.

(h) May rarely arise from the surface of bone in a subperiosteal location.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Axial skeleton

1. Involved initially in 70–80%. Initial changes in the sacroiliac joints followed by the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral regions. The entire spine may be involved eventually.

2. The radiological changes in the sacroiliac joints (see 3.12) are present at the time of the earliest spinal changes. MRI most sensitive technique for early disease and all changes except syndesmophytes.

3. Spondylitis – anterior and posterior erosion of vertebral end-plates (Romanus). Enthesitis of annulus fibrosis. Then sclerosis causing ‘shiny corner’ (osteitis).

4. Discovertebral – inflammatory involvement of intervertebral disc (Andersson).

5. Syndesmophytes – bony outgrowths from vertebral margins.

6. Squaring of vertebrae – due to bone proliferation.

7. Arthritis – facet, costovertebral and costotransverse joints (synovitis, erosion, ankylosis).

8. Enthesitis – interspinous ligaments with osteitis.

9. Ankylosis – fusion of spine from 5–7 plus bony extension through 4. Leads to ‘bamboo spine’.

10. Fracture – insufficiency in ankylosed spine (especially cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions).

11. Osteoporosis – with long-standing disease.

13. Arachnoiditis – rare and late. Arachnoid diverticulae, laminar erosions, dural calcification.

Appendicular skeleton

1. Hip – axial migration, concentric joint-space narrowing, cuff-like femoral osteophytes, acetabular protrusion. Symptoms may be dominant, leading to flexion contracture and ankylosis.

2. Shoulder – narrowing of glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints. Hatchet erosion at greater tuberosity.

3. Knee – tricompartment narrowing and erosion.

4. Hand and foot – asymmetric involvement; small erosion and osseous proliferation.

Extraskeletal

Jang, J. H., Ward, M. M., Rucker, A. N., et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: patterns of radiographic involvement – a re-examination of accepted principles in a cohort of 769 patients. Radiology. 2011; 258(1):192–198.

Lambert, R. G., Dhillon, S. S., Jaremko, J. L. Advanced imaging of the axial skeleton in spondyloarthropathy: techniques, interpretation, and utility. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2012; 16(5):389–400.

Asbestos inhalation

Pleura

1. Pleural plaques – commonest manifestation of asbestos exposure developing 20–30 years after exposure. Typically seen on parietal pleural on undersurface of ribs, diaphragmatic pleura and adjacent to spine; virtually pathognomonic. Sharply angulated, ‘holly-leaf’ opacities on chest radiography and sharply demarcated. Discrete ‘punched-out’ appearance at CT.

2. Benign pleural effusion – most common ‘early’ (< 10 years) manifestation; occurs in < 10%. Exudative fluid. May be unilateral or bilateral and may be followed by residual benign diffuse pleural thickening in around 50% or regions of rounded atelectasis (‘folded lung’).

3. Diffuse pleural thickening – less specific for asbestos exposure than plaques.

4. Rounded atelectasis – (folded lung, Blesovsky syndrome). Rounded mass, adjacent pleural thickening and parenchymal bands/distortion (‘comet tail’ appearance). Can be seen with other exudative effusions.

5. Malignant pleural mesothelioma – long latency (30–40 years). Lobulated pleural thickening involving mediastinal pleura ± large pleural effusion but minimal mediastinal shift. (NB. Can occur in peritoneum.)

Lung parenchyma

1. Asbestosis – long latency (30–40 years). Crocidolite most fibrogenic, chrysotile least. Histological and radiological appearances almost identical to those seen in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

2. Lung cancer – increased incidence even in the absence of a smoking history or asbestosis.

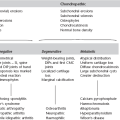

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease

1. Three manifestations which occur singly or in combination:

(a) Cartilage calcification (chondrocalcinosis).

(b) Crystal-induced acute synovitis (pseudogout)

(c) Structural joint abnormalities (pyrophosphate arthropathy).

2. Associated conditions are hyperparathyroidism and haemochromatosis (definite) and gout, Wilson’s disease and alkaptonuria (less definite).

3. Chondrocalcinosis involves:

(a) Fibrocartilage – especially menisci of the knee, triangular cartilage of the wrist, symphysis pubis and annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc.

(b) Hyaline cartilage – especially the wrist, knee, elbow and hip.

4. Synovial membrane, joint capsule, tendon and ligament calcification.

5. Pyrophosphate arthropathy is most common in the knee, wrist, metacarpophalangeal joint and acromioclavicular joint. Cartilage loss, subchondral plate sclerosis and subchondral cyst formation. It has similar appearances to osteoarthritis but with several differences:

(a) Unusual articular distribution – non-weight-bearing joints, e.g. wrist, shoulder.

(b) Unusual intra-articular distribution – the patellofemoral compartment of the knee and the radiocarpal compartment of the wrist.

(c) Numerous, large subchondral cysts.

(d) Marked subchondral collapse and fragmentation with multiple loose bodies simulating a neuropathic joint.

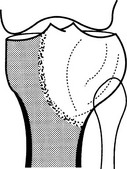

Chondroblastoma

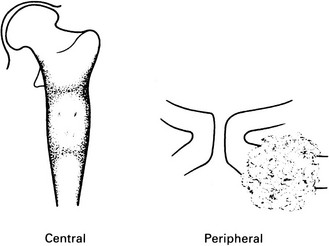

Chondrosarcoma

Peripheral

Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis

Simple

Deposition of coal and pigmented macrophages are the characteristic finding.

Crohn’s disease

Small bowel

1. Terminal ileum is the commonest site.

2. Asymmetrical involvement and skip lesions are characteristic. The disease predominates on the mesenteric border.

3. Aphthoid ulcers – the earliest sign in the terminal ileum and colon. May be invisible on CT and MRI.

4. Fissure ulcers – typically they are distributed in a longitudinal and transverse fashion. They may progress to abscess formation, sinuses and fistulae.

5. Blunting, thickening or distortion of the valvulae conniventes – the earliest sign in the small bowel proximal to the terminal ileum. Caused by hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue, producing an obstructive lymphoedema of the bowel wall. May give a granular appearance on barium studies.

6. ‘Cobblestone’ pattern – two possible causes:

(a) A combination of longitudinal and transverse fissure ulcers bounding intact mucosa.

(b) The bulging of oedematous mucosal folds that are not closely attached to the underlying muscularis.

7. Separation of bowel loops – due to thickened bowel wall and/or fat hypertrophy.

8. Strictures – may be short or long, single or multiple. Acute clinical obstruction is less commonly observed than subacute.

10. MRI signs of active disease include mural thickening, T2 hyperintensity, early enhancement (especially if trilayered), slow or absent motion and restricted diffusion.

Colon

Complications

2. Perforation – usually localized and results in abscess formation.

3. Toxic megacolon – more common in ulcerative colitis.

(a) Colon – less common than in ulcerative colitis, but this may be because more patients with Crohn’s disease undergo colectomy at an early stage.

(a) Erythema nodosum or pyoderma gangrenosum.

(i) Spondyloarthritis mimicking ankylosing spondylitis. It follows a course independent of the bowel disease and precedes it in 25% of cases.

(ii) Enteropathic synovitis, the activity of which parallels the bowel disease. The weight-bearing joints of the lower limbs, wrist and fingers are affected.

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome results from increased endogenous or exogenous cortisol.

Spontaneous Cushing’s syndrome is rare and due to:

1. Pituitary disease (Cushing’s disease): 80% (90% of these are due to adenoma and 20% have radiological evidence of an intrasellar tumour).

Iatrogenic

1. Growth retardation in children.

3. Pathological fractures which show excessive callus formation during healing; vertebral end-plate fractures, in particular, show prominent bone condensation.

4. Avascular necrosis of bone.

5. Increased incidence of infection – including osteomyelitis and septic arthritis (the knee is affected most frequently).

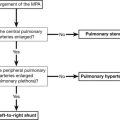

Cystic fibrosis

Thoracic findings

3. Mucus plugging – in central bronchi this may appear as nodules or filling-in of airways. In peripheral bronchi this appears as centrilobular nodules, often with the ‘tree-in-bud’ pattern.

4. Air-trapping – may result in generalized overinflation of the lungs with diaphragmatic flattening. Mosaic attenuation on inspiratory CT which is accentuated on expiratory sections.

5. Cystic changes – unusual in early disease. Not true cysts, but represent either areas of localized emphysema or cystic bronchiectasis.

7. Hilar enlargement – may be due to lymphadenopathy, which is common, or pulmonary arterial dilatation.

Hepatobiliary/pancreatic

Aziz, Z. A., Davies, J. C., Alton, E. W., et al. Computed tomography and cystic fibrosis: promises and problems. Thorax. 2007; 62(2):181–186.

King, L. J., Scurr, E. D., Murugan, N., et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic manifestations of cystic fibrosis: MR imaging appearances. Radiographics. 2000; 20(3):767–777.

Ruzal-Shapiro, C. Cystic fibrosis. An overview. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998; 36(1):143–161.

Down’s syndrome (trisomy 21)

James, A. E., Jr., Merz, T., Janower, M. L., et al. Radiological features of the most common autosomal disorders: trisomy 21–22 (mongolism or Down’s syndrome), trisomy 18, trisomy 13–15, and the cri-du-chat syndrome. Clin Radiol. 1971; 22(4):417–433.

Stein, S. M., Kirchner, S. G., Horev, G., et al. Atlanto-occipital subluxation in Down syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1991; 21:121–124.

Enchondroma

2. Sites – hands and wrists predominate (50%). Any other bones formed in cartilage.

(a) Diaphyseal or diametaphyseal.

(b) Well-defined lucency (1–2 cm) with a thin sclerotic rim.

(c) Expansion of the cortex without cortical breach, scalloping of inner cortex.

(d) Internal ground-glass appearance ± calcification/chondroid matrix.

(e) Pathological fracture – a frequent presenting complaint of enchondromas of the hands or feet.

Ewing’s sarcoma

2. Sites – femur, pelvis, shoulder girdle and ribs.

(a) Diaphyseal or, less commonly, metaphyseal.

(b) Ill-defined medullary destruction.

(c) ± Small areas of new bone formation.

(d) Periosteal reaction – lamellated (onion skin), Codman’s angle or ‘sunray’ speculation.

(e) Saucerization of the cortex due to periosteal destruction.

(f) Soft-tissue extension (best appreciated on MRI).

(g) Metastases to other bones and lungs.

(h) FDG/PET superior to bone scintigraphy in detection of bone metastases.

Fibrous dysplasia

Unknown pathogenesis. Medullary bone is replaced by fibrous tissue.

1. Diagnosis usually made between 3 and 15 years.

2. May be monostotic or polyostotic. In polyostotic cases the lesions tend to be unilateral; if bilateral then asymmetrical.

3. Most frequent sites are femur, pelvis, skull, mandible, ribs (most common cause of a focal expansile rib lesion) and humerus. Other bones are less frequently affected.

4. Radiological changes include:

(a) A cyst-like lesion in the diaphysis or metaphysis with endosteal scalloping ± bone expansion. No periosteal new bone. The epiphysis is only involved after fusion. Thick sclerotic border: ‘rind’ sign. Internally the lesion shows a ground-glass appearance ± irregular calcifications together with irregular sclerotic areas.

(b) Bone deformity, e.g. shepherd’s crook deformity of the proximal femur.

(d) Accelerated bone maturation.

(e) Skull shows mixed lucencies and sclerosis, mainly on the convexity of the calvarium and the floor of the anterior fossa.

(f) Leontiasis ossea is a sclerosing form affecting the face ± the skull base and producing leonine facies. In such cases extracranial lesions are rare. Involvement may be asymmetrical.

Giant cell tumour

1. Age – 20–40 years (only 3% occur before epiphyseal closure).

2. Sites – long bones (75–90%), distal femur especially; occasionally the sacrum or pelvis. Spine rarely.

(a) Epiphyseal and metaphyseal, i.e. subarticular.

(b) A lucency with an ill-defined endosteal margin.

(c) Eccentric expansion ± cortical destruction and soft-tissue extension.

(d) Cortical ridges or internal septa produce a multilocular appearance.

(e) Fluid levels on CT or MRI.

(f) 30% local recurrence rate and, rarely, pulmonary metastases.

Gout

Acute gouty arthritis

1. Monoarticular or oligoarticular; occasionally polyarticular.

2. Predilection for joints of the lower extremities, especially the first metatarsophalangeal joint (70%), intertarsal joints, ankles and knees. Other joints are affected in long-standing disease.

3. Soft-tissue swelling and joint effusion during the acute attack, with disappearance of the abnormalities as the attack subsides.

Chronic tophaceous gout

1. In 50% of patients with recurrent acute gout.

2. Eccentric, asymmetrical nodular deposits of calcium urate (tophi) in the synovium, subchondral bone, helix of the ear and in the soft tissues of the elbow, hand, foot, knee and forearm. Calcification of tophi is uncommon in absence of renal disease; ossification is rare.

3. Joint space is preserved until late in the disease.

4. Little or no osteoporosis until late, when there may be disuse osteoporosis.

5. Bony erosions are produced by tophaceous deposits and may be intra-articular, periarticular or well away from the joint. The latter two may be associated with an obvious soft-tissue mass. Erosions are round or oval, with the long axis in line with the bone. They may have a sclerotic margin. Some erosions have an overhanging lip of bone, which is strongly suggestive of the condition.

Haemangioma of bone

2. Sites – vertebra (dorsal lumbar) or skull vault.

(a) Vertebra – coarse vertical striations, usually affecting only the body but the appendages are, uncommonly, also involved.

(b) Skull – radial spiculation (‘sunburst’) within a well-defined vault lucency. ‘Hair-on-end’ appearance in tangential views.

(c) High signal on T1W and T2W MRI because of high fat content.

Haemochromatosis

1. AR primary abnormality of iron metabolism secondary to disorder of hepcidin, a polypeptide hormone produced in the liver.

2. May be secondary to alcohol, cirrhosis or multiple blood transfusions, e.g. in thalassaemia or chronic excessive oral iron ingestion.

3. Clinically – cirrhosis, skin pigmentation, diabetes (bronze diabetics; secondary to insulin resistance and cirrhosis), arthropathy and, later, ascites and cardiac failure.

4. Useful role for liver biopsy is the assessment of patients without typical haemochromatosis-associated HFE genotypes who have serum ferritin concentrations higher than 1000 µg/L, because many such patients have an inflammatory disease, not iron overload.

Bones and joints

2. Chondrocalcinosis – due to calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition (q.v.).

3. Arthropathy – resembles the arthropathy of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (q.v.), but shows a predilection for the metacarpophalangeal joints (especially the second and third), the midcarpal joints and the carpometacarpal joints. It also exhibits distinctive beak-like osteophytes and is less rapidly progressive.

Haemophilia

Joints

1. Knee, elbow, ankle, hip and shoulder are most frequently affected.

2. Soft-tissue swelling due to haemarthrosis, which may appear to be unusually dense owing to the presence of haemosiderin in the chronically thickened synovium.

3. Periarticular osteoporosis.

4. Erosion of articular surfaces, with subchondral cysts.

5. Preservation of joint space until late; ankylosis.

6. Epiphyseal overgrowth; leg-length discrepancies.

7. Knee – squaring of patella, widening of intercondylar notch and epiphyseal overgrowth.

Bones

1. Osteonecrosis – especially in the femoral head and talus.

2. Haemophilic pseudotumour – in the ilium, femur and tibia most frequently

Homocystinuria

Hurler’s syndrome

Hyperparathyroidism, primary

Causes

1. Adenoma of one gland (90%) (2% of adenomas are multiple).

2. Hyperplasia of all four glands (5%) (more likely if there is a family history).

4. Ectopic parathormone – e.g. from a carcinoma of the bronchus.

5. Multiple endocrine adenopathy syndrome (type 1) – hyperplasia or adenoma associated with pituitary adenoma and pancreatic tumour.

Bones

1. Osteopenia – uncommon. When advanced there is loss of the fine trabeculae and sometimes a ground-glass appearance.

2. Subperiosteal bone resorption – particularly affecting the radial side of the middle phalanx of the middle finger, medial proximal tibia, lateral and occasionally medial end of clavicle, symphysis pubis, ischial tuberosity, medial femoral neck, dorsum sellae, superior surface of ribs and proximal humerus. Severe disease produces terminal phalangeal resorption and, in children, the ‘rotting fence-post’ appearance of the proximal femur.

3. Diffuse cortical change – cortical tunnelling eventually leading to a ‘basketwork’ appearance. ‘Pepper-pot skull’.

4. Brown tumours – the solitary sign in 3% of cases. Most frequent in the mandible, ribs, pelvis and femora.

5. Bone softening – basilar invagination, wedged or codfish vertebrae, kyphoscoliosis, triradiate pelvis. Pathological fractures.

Joints

1. Marginal erosions – predominantly the distal interphalangeal joints, the ulnar side of the base of the little-finger metacarpal and the hamate. No joint-space narrowing.

2. Weakened subarticular bone, leading to collapse.

3. Chondrocalcinosis (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease) and true gout.

4. Periarticular calcification, including capsular and tendon calcification.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Acute HP

Symptoms (dyspnoea, dry cough, fever, malaise and myalgia) frequently mimic a viral-type illness, and develop 4–8 hours after exposure. Thus, imaging tests rarely performed but if undertaken chest radiograph is either normal or demonstrates subtle findings (small nodules, ground-glass opacification).

Subacute HP

1. Characterized clinically by acute episodes but with progressive decline in lung function.

2. On chest radiography profusion of fine nodules and ground-glass opacification bilaterally with sparing of lung bases.

3. On HRCT there is variably extensive ground-glass opacification (due to lymphocytic pneumonitis), centrilobular nodules (reflecting a cellular bronchiolitis) and lobular foci of decreased attenuation (with air-trapping on expiratory CT, reflecting the bronchiolocentric nature). A few scattered thin-walled cysts are seen in some patients.

Chronic HP

1. Usually due to persistent low-level exposure to organic antigen.

2. Reticular/reticulonodular pattern on chest radiography with a predilection for the upper zones. Lung volumes may be relatively preserved (possibly due to associated small airways [obstructive] disease).

3. At HRCT: reticular pattern, lobular areas of decreased attenuation, ground-glass opacification and tractional dilatation of bronchi and bronchioles; relative sparing of lower zones. Appearances may mimic those seen in cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Emphysema in farmer’s lung – even in lifelong non-smokers.

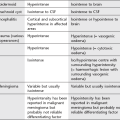

Hypoparathyroidism

1. Short stature, dry skin, alopecia, tetany ± mental retardation.

2. Skeletal changes affecting the entire skeleton.

3. Minimal, generalized increased density of the skeleton, but especially affecting the metaphyses.

4. Calcification of paraspinal ligaments (secondary to elevation of plasma phosphate, which combines with calcium, resulting in heterotopic calcium phosphate deposits).

Hypophosphatasia

Neonatal form

Infantile form

Hypothyroidism, congenital

Appendicular skeleton

1. Delayed appearance of ossification centres which may be

The femoral capital epiphyses may be divided into inner and outer halves.

2. Delayed epiphyseal closure.

3. Short long bones with slender shafts, endosteal thickening and dense metaphyseal bands.

4. Coxa vara with shortened femoral neck and elevated greater trochanter.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Polyarticular onset (23%)

1. Rheumatoid factor negative – 21% of total. Rheumatoid factor positive – 2% of total. F > M; onset > 11 years.

2. Arthritis predominates with a similar distribution to the systemic onset, but also including the small joints of the fingers and toes. The cervical spine is involved frequently and early.

3. Prolonged disease leads to growth retardation and abnormal epiphyseal development.

Radiological changes

1. Joint effusion – early finding.

2. Periarticular soft-tissue swelling – early finding.

3. Osteopenia – juxta-articular, diffuse or band-like in the metaphyses, the latter particularly in the distal femur, proximal tibia, distal radius and distal tibia.

4. Periostitis – common. Mainly periarticular in the phalanges, metacarpals and metatarsals, but when diaphyseal will eventually result in enlarged rectangular tubular bones.

5. Growth disturbances – epiphyseal overgrowth; premature fusion of growth plates; short broad phalanges, metacarpals and metatarsals; hypoplasia of the temporomandibular joint; micrognathia; leg-length discrepancy.

6. Subluxation and dislocation – common in the wrist and hip. Atlantoaxial subluxation is most frequent in seropositive juvenile-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Protrusio acetabuli of the hip.

7. Bony erosions – late manifestation; predominantly knees, hands and feet.

8. Joint-space narrowing – late manifestations due to cartilage loss.

9. Bony ankylosis – late finding; especially carpus, tarsus and cervical spine.

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

Single-system disease

High chance of spontaneous remission and favourable outcome.

Bone LCH

1. Commonest in 4–7-year-olds, who present with bone pain, local swelling and irritability.

2. 50–75% have solitary lesions. When multiple, usually only two or three. Long bones, pelvis, skull and flat bones are the most common sites involved. 20% of solitary lesions become multiple. Biopsy of the lesion for diagnosis may induce a healing reaction.

3. Radiological changes in the skeleton include

(a) Well-defined lucency in the medulla ± thin sclerotic rim. ± Endosteal scalloping. True expansion is uncommon except in ribs and vertebral bodies. ± Overlying periosteal reaction.

(b) Multilocular lucency, without expansion, in the pelvis.

(c) Punched-out lucencies in the skull vault with little or no surrounding sclerosis. May coalesce to give a ‘geographical skull’.

(d) Destructive lesions in the skull base, mastoids, sella or mandible (‘floating teeth’).

Lung involvement

1. Lung involvement in children, usually part of multisystem disease

(a) Multiple nodules which cavitate.

(b) May be complicated by pneumothorax and pleural effusion.

(c) Not associated with a worse prognosis – in children < 10 years may regress spontaneously.

2. Lung involvement in adults associated with a worse prognosis, most common in the 3rd decade, associated with a worse prognosis and strong smoking association

Multisystem disease

Hand–Schüller–Christian disease

1. Generally occurs < 10 years but may appear in twenties or thirties. Commonest in 1–3-year-olds.

2. Osseous lesions together with mild to moderate visceral involvement which includes lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, skin lesions, diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos and pulmonary disease, including pulmonary fibrosis.

3. Bone lesions are similar to eosinophilic granuloma, but more numerous, more destructive and widely distributed, with a predilection for the skull base.

Lymphoma

(Intrathoracic) lymph-node enlargement

1. 66% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease have intrathoracic disease and 99% of these have intrathoracic lymphadenopathy.

2. 40% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have intrathoracic disease and 90% of these have intrathoracic lymphadenopathy.

3. Nodes involved are (in order of frequency) anterior mediastinal, paratracheal, tracheobronchial, bronchopulmonary and subcarinal. Involvement tends to be bilateral and asymmetrical, although unilateral disease is not uncommon.

4. Nodes show a rapid response to radiotherapy, and ‘egg-shell’ calcification of lymph nodes may be observed following radiotherapy.

Pulmonary disease

1. More common in Hodgkin’s disease than non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

2. Unusual in the absence of lymph-node enlargement, but may be the first evidence of recurrence after radiotherapy.

3. Most frequently one or more large opacities with an irregular outline. ± Air bronchogram.

4. Lung collapse caused by endobronchial lymphoma or, less frequently, extrinsic compression (collapse is less common than in bronchial carcinoma).

5. Lymphatic obstruction → oedema or lymphangitis carcinomatosa.

6. Miliary or larger opacities widely disseminated throughout the lungs.

7. Cavitation – eccentrically within a mass and with a thick wall (more common than in bronchial carcinoma).

8. Calcification following radiotherapy.

Solid organs

1. In general may be focal, multifocal or diffuse.

(a) Hypoattenuating nodules (HU > water); may resemble cysts on US scan.

(b) Diffuse involvement may result in organ enlargement only with no focal lesion.

(c) May be more prominent on MRI (low on T1, moderately high on T2).

(d) Difficult to differentiate from fungal infection (fungal microabscesses tend to be smaller with more heterogeneous enhancement).

(e) Usually secondary; primary hepatic/splenic lymphoma very rare.

(a) Involved in 30% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

(b) Diffuse involvement may mimic pancreatitis (organ enlargement, peripancreatic fat infiltration, reduced contrast enhancement).

(c) Focal involvement may mimic adenocarcinoma, but duct dilatation, gland atrophy and vascular invasion are rare with lymphoma.

Gastrointestinal lumen

1. In general may cause mild to moderate wall thickening, luminal constriction of dilatation and/or cavitation. Usually homogeneous and hypoattenuating after contrast.

2. Bulky lymph nodes typically present.

3. Infiltration may cause tube-like aperistaltic segment and/or aneurysmal dilatation of bowel.

Stomach

1. Primary lymphoma accounts for 2.5% of all gastric neoplasms, and 2.5% of lymphomas present with a stomach lesion. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma accounts for 80% (most common is MALT, related to Helicobacter pylori).

2. The radiological manifestations comprise

(a) Diffuse mucosal and fold thickening and irregularity ± decreased distensibility and peristaltic activity. ± Multiple ulcers.

(b) Smooth nodular mass ± central ulceration. Surrounding mucosa may be normal or show thickened folds.

(c) Single or multiple ulcers with irregular margins.

(d) Thickening of the wall with narrowing of the lumen. If the distal stomach is involved there may be extension into the duodenum.

Small intestine

1. Usually secondary to contiguous spread from mesenteric lymph nodes. Primary disease only in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. 20% of small bowel tumours are lymphoma.

2. Usually more than one of the following signs is evident

(a) Irregular mucosal infiltration → thick folds ± nodularity.

(b) Irregular polypoid mass ± barium tracts within it or central ulceration.

(c) Annular constriction – usually a long segment.

(d) Aneurysmal dilatation, with no internal mucosal pattern.

(e) Polyps – multiple and small or solitary and large. The latter may induce an intussusception.

Nodal disease

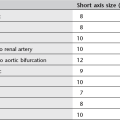

1. Normal lymph nodes are usually 3–10 mm in diameter. Abdominal lymph nodes are likely abnormal if > 10 mm diameter. A localized cluster of lymph nodes 6–10 mm in diameter should be considered highly suspect.

2. PET/CT improves accuracy of local staging and response assessment compared to conventional CT.

3. Negative PET imaging does not exclude viable disease, and a positive PET scan does not necessarily indicate viable tumour.

Skeleton

1. Radiological involvement in 10–20% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease (50% at autopsy).

2. Involvement arises from either direct spread from contiguous lymph nodes or infiltration of bone marrow (spine, pelvis, major long bones, thoracic cage and skull are sites of predilection).

3. Patterns of bone involvement are

(b) Mixed lytic and sclerotic.

(c) Predominantly sclerotic – de novo or following radiotherapy to a lytic lesion.

(d) ‘Moth-eaten’ – characteristic of round cell malignancies.

4. In addition, the spine may show

(a) Anterior erosion of a vertebral body caused by involvement of an adjacent paravertebral lymph node.

5. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.

6. Plain film may be negative with extensive disease on MRI.