CHAPTER 36 Alloplastic chin augmentation

Physical evaluation

Lower lip analysis

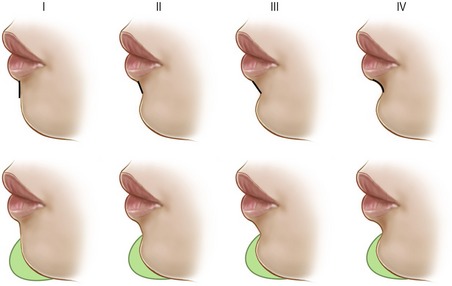

The inclination of the lower lip white roll to labiomental fold affects perception of chin size after augmentation or reduction (Fig. 36.1). If the inclination of the lower lip is vertical and the demarcation between the lip and chin is poor, the patient will appear to have an excessively large chin after augmentation. This is particularly true if a full height implant is incorrectly used. The lower lip analysis is intermingled with the labiomental fold analysis because the lip inclination helps define the labiomental fold. If a patient has a deep overbite and the lip is everted, then the lower lip will have an oblique inclination. The obliquity of the lower lip will contribute to a deeper labiomental fold with a more acute angle. The surgeon should note this because an alloplastic implant that is too tall will deepen the fold and make the labiomental fold angle even more acute. If it is helpful, the lower lip inclination can be classified as follows: Type I is nearly vertical, type II is slightly posterior, type III is significantly posterior, and type IV is most oblique.

Labiomental fold analysis

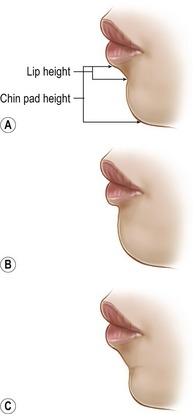

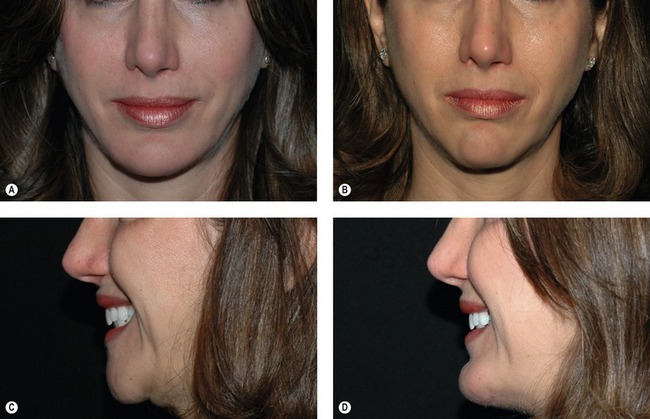

If two chins project exactly the same amount, the chin with the higher and/or shallower labiomental fold will always appear larger from the front (Fig. 36.2). Since the chin is primarily seen as the pad, the labiomental fold defines the apparent vertical height of the chin. Thus, augmenting a patient with a high, shallow labiomental fold tends to increase the appearance of the vertical height of the chin as well as its overall size. To overcome this problem, the surgeon should reduce the vertical height of the implant (see below) to limit augmentation to the lower pogonion. If the chin is long with a high fold, the patient may need both a vertical chin reduction and a sagittal augmentation. In contrast, a patient with a low, distinct labiomental fold will tolerate chin augmentation much better because the implant accentuates only the chin pad.

Static and dynamic chin pad analysis

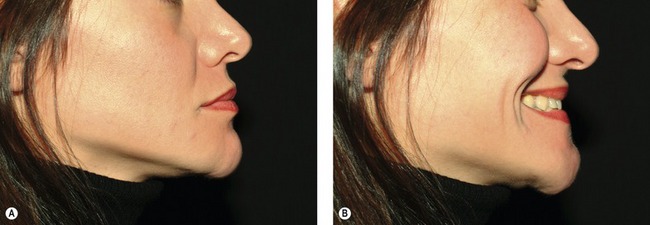

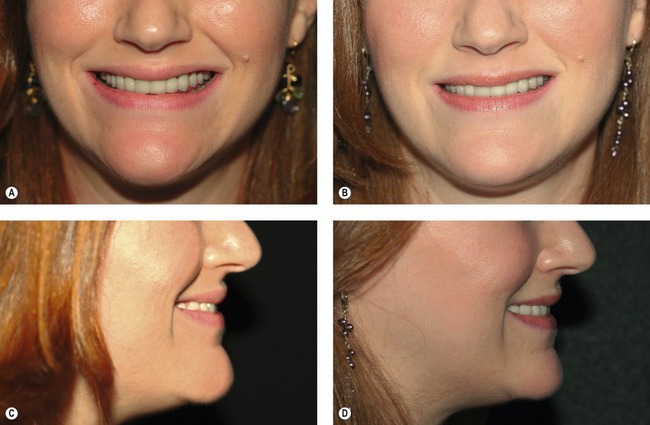

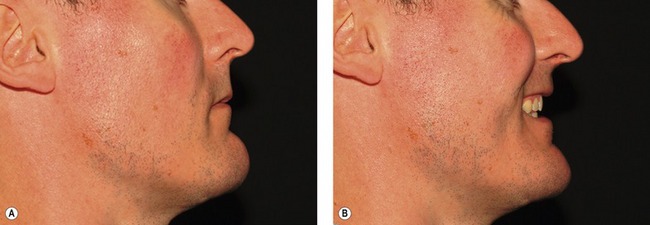

The observer will note that when a chin pad is thick, a smile usually improves the patient’s appearance because the thick pad becomes effaced (Fig. 36.3). In contrast, as a thin chin pad is effaced upon smiling, the chin appears even more prominent (Fig. 36.4). During a normal smile, elevation of the corners of the mouth brings the chin pad superiorly. Some patients have a horizontal non-lifting smile such that the lower lip depressors are unopposed. Unopposed activation of the lower lip depressors produces dynamic chin pad ptosis with smiling as the chin pad drops (Fig. 36.5).

Fig. 36.3 Effect of smiling on a thick chin pad. A, Lateral photograph of patient in repose. B, During a smile, the thick chin pad becomes effaced, usually improving the appearance of the chin.

Submental analysis

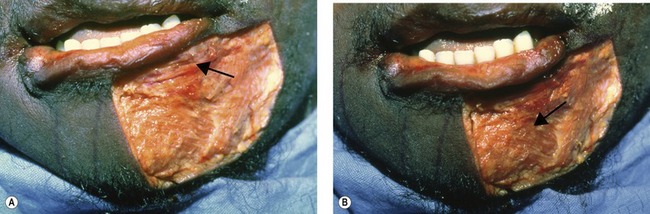

During the physical evaluation, the surgeon must keep in mind that chin augmentation in women should be conservative. Female patients are more apt to complain that a chin implant is too large and request removal. It is important to note, that removing an excessively large implant is no simple matter. Removing an implant can result in surface irregularities and fasciculations or the redundant tissue can cause static chin pad ptosis (Fig. 36.6). When evaluating a patient with an excessively large implant, rather than simply removing the implant, we recommend that the existing implant be exchanged with a smaller implant (see below) or an osseous genioplasty should be performed. The new implant or osseous advancement will support the chin pad soft tissues and reduce fasciculations and/or ptosis.

Anatomy

On the labial surface of the mandible in the midline is the symphyseal spine which is also referred to as the surgical spine. The symphyseal spine divides to enclose a triangular eminence called the mental protuberance. The center of the mental protuberance is depressed, but its raised lateral borders form the mental tubercles. On either side of the upper symphysis, just below the mandibular incisors are the incisive fossae. The incisive fossae are the origins of the mentalis muscle. The mentalis muscles coalesce to form the bulk of the chin pad and they insert into the chin pad dermis to maintain lip position in repose and elevate and protrude the lower lip in animation. The mentalis muscles have horizontal and oblique components (Fig. 36.7). The upper horizontal portion which originates just below the attached gingiva is responsible for the lip level and position in repose. The function of the horizontal portion of the mentalis muscle, in isolation or in conjunction with the orbicularis oris, determines the shape and position of the labiomental fold as well as the lower lip position. The oblique portion of the mentalis muscles may fuse centrally (as in most cases) or remain separate superiorly or inferiorly to form a cleft. Thus, a cleft in the chin is, in essence, a muscle deficient zone. The oblique portion of the mentalis muscles tends to pull the chin pad against the mandible, drawing up the lip and allowing us to pout. Finally, the oblique fibers also elevate the central portion of the lip. Lateral to the mentalis muscle, beneath the second premolar midway between the superior and inferior borders of the body are the mental foramina. In a vertically short mandible the foramina may be higher than expected.

The lingual surface of the mandible is marked in the midline by a median furrow. Inferior to the median furrow are the bilateral parasymphyseal mental spines. The mental spines are the origin for the genioglossus muscles. Immediately inferior to the mental spines is a median impression that is the origin of the geniohyoid. Also inferior and lateral to the mental spines are oval depressions for the attachment of the anterior bellies of the digastrics. Running distal and superior from either side of the lower part of the symphysis are the mylohyoid lines which give origin to the mylohyoid muscles bilaterally.

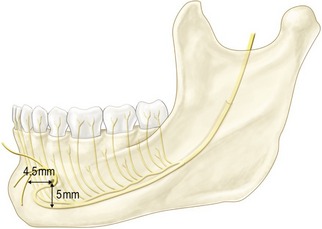

Sensory innervation of the chin is provided for the most part by the mental nerves. The mental nerve is a branch of the third division of the trigeminal nerve that exits the skull base through the foramen ovale and gives off nine branches including the inferior alveolar nerve. At the lateral pterygoid, the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle passes between the sphenomandibular ligament and the ramus and enters the mandibular foramen on the medial surface of the ramus. The mandibular foramen is usually located about 2 cm from the anterior border of the ramus and nearly opposite the antilingula (on the buccal surface of the mandible). The inferior alveolar nerve is a sensory nerve, but a few motor and sensory fibers from the mylohyoid nerve run alongside. The inferior alveolar nerve usually travels in a single canal (2.0–2.4 mm in diameter) to supply the mandibular molars, premolars, and adjacent gingiva (Fig. 36.8). The terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve passes as much as 4.5 mm below and 5 mm mesial to the mental foramen before looping up to emerge as the mental nerve. The mental nerve innervates all of the skin of the chin (except for quarter size patches of skin on either side of the chin pad), the lower lip, the lower lip mucosa, the gingiva, the incisors, and the canines. The quarter size patches of skin on either side of the chin pad are supplied by a sensory branch of the mylohyoid nerve.

Fig. 36.8 The inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle enters the mandibular foramen on the medial surface

Normal chin pad soft tissue thickness is 8–11 mm. Palpation of the soft tissue thickness of the chin is essential for accurate anatomic assessment of the chin. When the pad is thick, the observer will note that a smile usually improves the patient’s appearance as the thick pad is effaced. In contrast, as a thin chin pad is effaced with a smile, the chin appears more prominent. Chin pad fasciculations are usually a result of mentalis strain to obtain lip competence or seal. During a normal smile, the zygomaticus and levator muscles elevate the corners of the mouth moving the chin pad superiorly. Some patients have a horizontal non-lifting smile (risorius dominated) such that the lower lip depressors are unopposed; this results in dynamic chin pad ptosis with smiling (Fig. 36.5). All muscles of facial expression around the chin are innervated by branches of the facial nerve except for the mylohyoids and anterior bellies of the digastrics which are innervated by the third division of the trigeminal nerve.

Technical steps

The facial midline, from the labiomental fold to the hyoid and the intended incision is marked. During the first 10 minutes, while the last injection of local anesthesia is taking effect, we perform the following steps: (1) the upper 30–50% of the implant is carved down with a burr or knife; (2) the lateral wings of the implant are tapered; (3) the upper edge of the implant is tapered 45° angle with a burr or knife; (4) for textured implants, two pilot holes are drilled in each half of the implant (in some cases when the implant is short, one hole per side is satisfactory). The first pilot hole is drilled about 3–5 mm from the midline and the second pilot hole is drilled halfway between the first and the end of the implant; (5) textured implants can be divided in the midline (Fig. 36.9).

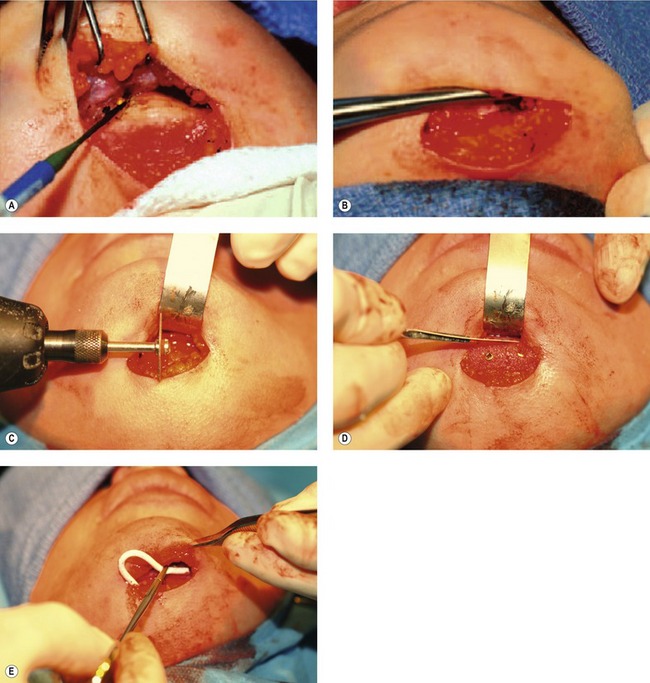

An intraoral or submental incision may be performed. The choice is based on surgeon preference, but we find that it is much easier to precisely position an implant through a submental incision. The intraoral incision is selected when mentalis muscle correction (e.g. resuspension) is necessary. The submental incision provides excellent exposure and enables the operating surgeon to remove skin and/or pre/subplatysmal adipose. Through either access incision, electrocautery dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous tissues to the periosteum. Electrocautery is used to clear the mandibular border from canine to canine and then a periosteal elevator is used to complete the lateral pockets. At the most lateral extent of the dissection, the elevator is levered up to gain additional room in the pockets. (If a silicone implant will be used, we limit the size of the dissection pocket in order to help secure the implant.) Next, the midline of the mandible at the menton is marked with electrocautery, bur or drill. This is a key step that should never be omitted (Fig. 36.10).

Fig. 36.10 Placement of an alloplastic chin implant. A, Through either access incision, electrocautery dissection is carried down through the subcutaneous tissues to the periosteum. Electrocautery is used to clear the mandibular border from canine to canine. B, At the most lateral extent of the dissection, the elevator is levered up to gain additional room in the pockets. (If a silicone implant will be used, we limit the size of the dissection pocket in order to help secure the implant.) C, The midline of the mandible at the menton is marked. D, The textured implant is inserted into the dissection pocket and the central portion of the implant is aligned with the midline menton mark and a screw is placed through the medial pre-drilled pilot hole. This screw is partially tightened. Then the lateral segment of the implant is exposed and held along the inferior border. The second screw (distal) is placed through the pre-drilled implant pilot hole and then both screws are tightened completely, so that the screw heads are below the implant surface. This allows for further reduction of the anterior surface of the implant, if necessary (depicted here with a knife). E, The incision is closed in layers and a small drain is brought out through the skin caudal to the access incision.

When using a textured implant, we commonly divide it in half. The first half is inserted into the dissection pocket and the central portion of the implant is aligned with the midline menton mark and a screw is placed through the medial pre-drilled pilot hole. This screw is partially tightened. Then the lateral segment of the implant is exposed and held along the inferior border (Fig. 36.10). The second screw (distal) is placed through the pre-drilled implant pilot hole and then both screws are tightened completely, so that the screw heads are below the implant surface. This allows for further reduction of the anterior surface of the implant, if necessary. The same procedure is performed on the opposite side of the mandible.

A small drain is passed from the implant to exit the skin caudal to the submental incision. A 4-0 polypropylene is passed through the drain and skin and then tied. The submental incision is then closed in three layers: muscle, subcutaneous tissues, and skin. The procedure usually takes about 40 minutes. Typical results are shown in Figs 36.11 and 36.12.

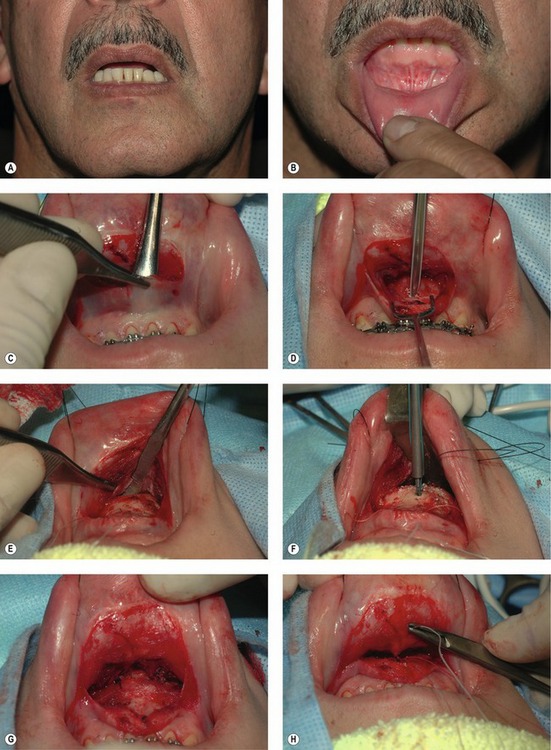

When a patient has a mentalis origin greater than 8 mm below the attached gingival margin and he/she is unhappy with lip volume loss, difficulty maintaining lip closure, or excessive amount of mandibular tooth show, the horizontal portion of the mentalis muscle can be resuspended (i.e. mentalis reefing) (Fig. 36.13). In this case, an intraoral incision is necessary. An incision is made superior to the labiobuccal sulcus on the lip and dissection is carried down to bone. The atrophic/malpositioned mentalis origins are divided and subperiosteal dissection is performed widely from mental nerve to mental nerve and down to the menton. The inferior symphyseal periosteum is scored and subperiosteal dissection is performed along the inferior border of the mandible from bicuspid to bicuspid and 4–5 cm submentally. This dissection is essential to mobilize and resuspend the mentalis superiorly. The proximal cuff of labiobuccal sulcus mucosa is elevated to expose the alveolar bone. An absorbable bone anchor is placed between the tooth roots at the superior edge of the incisive fossa (i.e. true mentalis origin). If a textured implant is placed the inferior border of the mentalis should be sutured to the implant, otherwise a second bone anchor should be placed at the level of the pogonion. (Suturing the inferior mentalis to a textured implant or using a pogonial bone anchor off-loads the weight of the chin allowing the surgeon to reposition the origin of the muscle at the incisive fossae.) Once the inferior portion of the mentalis is supported, the alveolar bone anchored sutures are placed through the mentalis muscle to elevate it superiorly into a more natural anatomic position.

Fig. 36.13 Resuspension of the mentalis muscle origin. If a patient has a mentalis origin greater than 8 mm below the attached gingival margin and is unhappy with excessive mandibular tooth show, the mentalis muscle origins can be resuspended. A, Patient in repose with excess mandibular tooth show. B, Mentalis muscle origin is greater than 8 mm below the attached gingiva. C, Through an intraoral incision and subperiosteal dissection is performed to expose the alveolus and menton from canine to canine. D, An absorbable bone anchor is placed between the tooth roots at the superior edge of the incisive fossa (i.e. true mentalis origin). E, Subperiosteal dissection is performed along the inferior border of the mandible and 4–5 cm submentally. This dissection is essential to mobilize and resuspend the mentalis superiorly. F, A second bone anchor should be placed at the level of the pogonion. G, Tying the pogonial bone anchor supports the chin. H, The alveolar bone anchored sutures are placed through the mentalis muscle to elevate it superiorly into a more natural anatomic position.

Secondary alloplastic chin augmentation can be challenging. If the previous implant is too large or has migrated superiorly, the implant pocket cannot be relied upon to maintain a new silicone chin implant in the correct position. Therefore, when reoperating on a chin implant, we approach the chin through a submental incision (irrespective of the initial access route for implant placement). We always use a textured secured chin implant for revision chin augmentation. Importantly, if the first implant was too large, we always down-size the implant or perform an osseous genioplasty. We never remove an implant without replacement (alloplastic or osseous) because the unsupported soft tissues and capsule would result in ptosis and contour irregularities (Fig. 36.6).

Complications

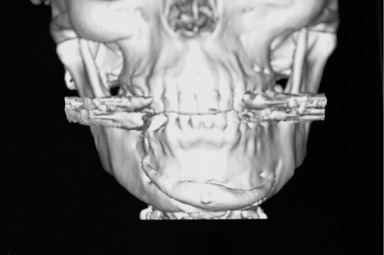

Improperly placed or secured implants can produce step-off deformities which can be palpated and sometimes seen. If the implant pocket is too small the implant can fold resulting in skin contour irregularity and dimpling. Conversely, when using a silicone implant, if the pocket is too large the implant can become displaced or malpositioned. Displacement/malposition of an implant is usually due to poor pocket design, inadequate fixation, or to placement within a soft-tissue pocket rather than a subperiosteal pocket. Movement or pressure from a high-riding implant may result in erosion of the mandible or the implant may impinge on the mental nerve (Fig. 36.14). Displaced/malpositioned implants are treated by removal and replacement with a textured secured implant through a submental incision or by osseous genioplasty. Early postoperative infections (1.4%) and seroma (<0.5%) affect few patients. The incident of alloplastic chin implant removal is relatively low (1.6%). Removing a malpositioned, displaced, infected, or wrong-sized implant without replacement usually causes chin surface irregularities and ptosis. In some cases, implant removal and osseous genioplasty may be the only reliable solution.

Fig. 36.14 Three dimensional CT scan of a displaced/malpositioned implant impinging on the right mental nerve.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• The chin should be analyzed with respect to facial balance rather than anthropometric numerical standards. Facial analysis should be performed to assess the lower lip inclination, labiomental fold height and depth, chin pad thickness, static and dynamic ptosis with smile, bony chin, and submenton. Static and dynamic photographs are necessary.

• Implants should not be used directly off the shelf. Implants tend to be designed too large (i.e. too long and too high). Since pogonion projection is required only at the inferior one centimeter of the chin, there is rarely a reason to use an unmodified, full-height implant.

• The superior 30–40% of an implant can usually be removed. The lateral wings can be shortened or tapered. Sometimes the inferior part of the implant must be reduced laterally, so it does not hang below the inferior border of the mandible.

• If the surgical spine beneath the labiomental fold is prominent, the upper part of the implant will make the labiomental fold too acute. Therefore, the surgical spine can be reduced.

• Implant carving and preparation can be performed while the last local anesthetic injections are setting up. The implant is placed exactly along the mandibular border in order to avoid palpability.

• If the vertical height of the mandible is short, you must see the mental foramina because they may be very low. In this case, the implant can easily impinge on the mental nerves as they exit their foramina.

• In secondary surgery, if you are replacing a silicone implant, with a textured implant, consider suturing the central portion of the soft tissue capsule to the anterior-superior surface of the new textured implant in order to eliminate dead space. This may require 1–2 sutures to effectively eliminate the dead space.

• Place and countersink all screws in the lower third of the implant, so that final implant contouring can be done without encountering the screws.

Pitfalls

• The most common mistake in chin surgery is to consider only the bony component of the chin.

• Augmenting a chin with a high or indistinct labiomental crease gives the appearance of increased lower face height as opposed to increased projection.

• Removal of previous chin implant without replacement with a new implant or an osseous genioplasty results in chin ptosis and unpredictable contour of the chin pad.

• Overcorrection of the chin can be acceptable in men, but is poorly tolerated in women.

• There is no implant that reliably increases the vertical length of the chin. Do not attempt to increase vertical height of the chin by allowing the implant to hang below the inferior border of the mandible.

Summary of steps

1. An analysis of the face is performed to assess the lower lip inclination, labiomental fold height and depth, chin pad thickness and ptosis, bony chin, and submenton.

2. The chin dysmorphology is diagnosed and treatment plan selected.

3. The patient is sedated with oral diazepam and loprazolam.

4. The patient’s facial midline and intended incisions are marked.

5. Bilateral inferior alveolar nerve block with 1% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine. Ten minutes later, mental, jaw line, and submenton local anesthetic injections are performed.

6. An intraoral or submental incision is made and subperiosteal dissection is performed from canine to canine and along the lower border of the mandible.

7. If a textured implant is used, the superior 30–40% of the implant is removed and the lateral wings are tapered with a burr. The implant is divided in the midline and two holes are predrilled in each half of the implant. The implant is secured with screws.

8. If a silicone implant is used, the superior 30–40% of the implant is removed. The dissection pocket must be precisely confined to the lower border of the mandible. The silicone implant may be secured with sutures.

9. The incision is closed. A small suction drain is optional.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr Barry M. Zide for his valuable contributions to this chapter.

Spector JA, Warren SM, Zide BM. Chin surgery: VI. Treatment of an unusual deformity, the tethered microgenic chin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1053–1059.

Warren SM, Spector JA, Zide BM. Chin surgery: V. Treatment of the long, nonprojecting chin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:760–768.

Warren SM, Spector JA, Zide BM. Chin surgery: VII. The textured secured implant – a recipe for success. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1378–1385.

Zide BM, Boutros S. Chin surgery: III. Revelations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1542–1550.

Zide BM, Longaker MT. Chin surgery: II. Submental ostectomy and soft-tissue excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1854–1860.

Zide BM, Pfeifer TM, Longaker MT. Chin surgery: I. Augmentation – the allures and the alerts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1843–1853.

Zide BM, Swift R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:840–851.

Zide BM, Warren SM, Spector JA. Chin surgery: IV. The large chin – key parameters for successful chin reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:530–537.

Zide BM. The mentalis muscle: an essential component of chin and lower lip position. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1213–1215.