Chapter 9 Allografts

Graft Sterilization and Tissue Banking Safety Issues Graft Sterilization and Tissue Banking Safety Issues

OVERVIEW OF CURRENT ALLOGRAFT TISSUE USE

Allografts are commonly used in the United States and their acceptance, availability, and safety profile have never been stronger. The numbers of grafts harvested and distributed by tissue banks in the United States have steadily increased. The American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB) recovered approximately 17,000 donor grafts in 1996, and this had increased to approximately 23,000 donor grafts in 2003.14 Over 300,000 musculoskeletal tissues were distributed in 1996, and about 1.3 million musculoskeletal grafts were distributed in 2003. It has been estimated that there have been about 4 to 5 million tissue transplants between 2000 and 2005.25 Issues relating to graft procurement, sterilization, and overall tissue banking safety continue to be a concern. A recent survey by the American Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Society of over 350 members documented a concern and widespread misunderstanding of the tissue banking industry.14 Over 80% used allografts and almost 75% were concerned about safety and sterilization. Most surgeons reported not knowing much about sterilization processing and about half did not know whether their tissues were sterilized or which sterilization process was used.

Critical Points OVERVIEW OF CURRENT ALLOGRAFT TISSUE USE

CURRENT TISSUE BANK REGULATION

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the government authority that regulates musculoskeletal tissue. The FDA authorizes and enforces tissue regulation to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases between states or from foreign countries into the United States. In 2004, the FDA published the “Final Rule: eligibility and determination of donors of human cells tissues and cellular and tissue-based products.”20 Also published in 2004 was the Draft guidance for industry: eligibility to determination for donor of human cells, tissue and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps).22 In 2005, the FDA implemented the industry requirements for good tissue practices (GTP) for all establishments that manufacture human cell and cellular tissue–based products. The purpose of these new government regulations was to set standards for tissue banking and prevent the potential introduction, transmission, and spread of communicable diseases by allograft tissues. These standards are also in place to prevent contamination during the process of screening, procuring, and processing of allograft tissue. All tissue establishments are required to register with the FDA.

Critical Points CURRENT TISSUE BANK REGULATION

This registration and the GTP rule allow the FDA to inspect facilities anytime without notice. FDA regulations require donors to be screened and tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) types 1 and 2, hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV, HCV), Treponema pallidium, and human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies.23 In August 2007, the FDA increased screening standards by requiring recovery tissues to be negative for HIV 1 nucleic acid testing (NAT), HCV NAT, and hepatitis B core antibody (total). All tissue banks must keep a document of these tests.

The AATB, founded in 1976, is a nonprofit organization that establishes and sets voluntary standards for safe transmittal of cells and tissues.3 This organization consists of both accredited tissue banks and individual members. It promotes education and research. The goal of the AATB is to educate and prevent disease transmission with cell and tissue allografts.

The AATB first published “the standards for tissue banking” in 1984 to give recommendations and guidelines to tissue banks. These safety guidelines are periodically reviewed and updated.3 All members of the AATB must follow the published tissue bank standards for donor suitability determination (screening and testing), donor consent/authorization, tissue recovery, quality insurance/quality control, record keeping, processing, labeling, storage, distribution, and safety. The AATB has been doing on-site inspections and accreditations since 1986. Tissue banks are to be inspected every 3 years, and renewal of accreditation is granted after a formal review of any reinspection. It should be noted that membership in this trade organization is voluntary. The AATB does not have any formal disciplinary powers outside of restriction or exclusion from the organization itself. The FDA is the ultimate enforcer of tissue banks, with powers of warning letters and possibly the ultimate shutdown of the tissue banks itself.

It is currently estimated that 90% of musculoskeletal tissues are distributed through AATB-accredited tissue banks.25 Through 2006 there were 95 accredited tissue banks with 70 banks involved in musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and skin allograft tissues. The AATB requires infectious disease testing for HIV types 1 and 2 antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, total antibody to hepatitis B core (immunoglobulin [Ig] G and IgM), human T-cell lymphotrophic virus (HTLV)–I/HTLV-II antibody, HCV antibody, NAT for HCV and HIV-1, and a syphilis assay. AATB also requires discarding allografts with cultures that are positive for clostridium or Streptococcus pyrogenes (group A streptoccoccus). Any positive final culture requires discarding of that tissue.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) first released an advisory statement regarding tissue allograft use in 1991 and updated this in 2001 and 2006.1 The AAOS urged all tissue banks to follow the AATB guidelines and standards.

The Department of Health and Human Services, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has begun to improve communication within the tissue/organ community to identify and track tissues.15 A single unique national identification number will be applied to donors and tissues that then can be tracked during the entire donation and transplantation process. This is an ongoing effort to help monitor individual tissues and ultimately improve our tissue knowledge base and increase safety standards.

In 2005, the Joint Commission (JC), which is formally known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), also set standards for storage of tissues intended for transplantation for hospitals and outpatient surgery centers.13 The JC is an independent organization separate from the FDA and is the nation’s oldest and largest accrediting body in health care. Their standards will help ensure safety at hospitals and surgery centers that handle tissues through the monitoring and recording of the use and storage of allograft tissues.

ALLOGRAFT TISSUE PROCESSING

Critical Points TISSUE PROCESSING

Step One: Donor Screening

There is always a concern for the window period for viruses when the donor does not have any detectable viral antibodies or immunogens.7 With NAT, this window period can be as low as 7 days for HIV and HCV and up to 20 days for HBV. The risk of transplant tissues from HIV-infected donors has been estimated to be 1 in 173,000 to 1 in 1,000,000.5,11,27 Current estimates for Americans infected with HIV vary from 850,000 to 950,000. The risk of contracting HBV and HCV from an infected donor is much higher than that of HIV. The general population is estimated to have 1.2 million Americans infected with HBV and approximately 4 million with HCV.11 Approximately 50% of these HCV patients do not know they are carriers and about 50% acknowledge no risk history associated with HCV. The current risk of transplanted tissues from HCV-infected donors is estimated to be 1 in 421,000.27 In reality, the actual number of potential tissue donors who are infected with these viruses is not known. Blood donation data give a general indication of the inherent risk associated with the screening and processing of human blood. The risk of bacterial infection from screening and processing has been reported to be 1 in 3500 to 1 in 5000.2,8,17

The National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System of the CDC has reported a postoperative orthopaedic infection rate ranging from 0.6% to 2%.11 A recent government workshop documented 19 infection reports in a 5-year period when approximately 4 to 5 million tissues were distributed.16 The risk of infection with all these transplanted tissues is very low; the precise number is difficult to evaluate. Overall, the current risk of allograft-transmitted infection in patients is much less than the overall risk of a generalized perioperative nosocomial infection. This is especially true with tissues used from certified AATB-associated banks.

There are several new pathogens on the horizon about which we have no information. This includes the West Nile virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the corona virus. There are no current screening tests for prion diseases associated with transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and its variants.21

Step Two: Tissue Processing

Recovery is done most often in an operating room theater or a designated recovery center. Occasionally, this can be done in a morgue. A team of technicians assist in this surgical procedure. Operating room techniques including preparing and draping the donor are similar to those of standard operating protocols. Sterile technique is used with drapes, gowns, gloves, and sterile instruments. Each tissue is procured, cultured, wrapped, labeled, sealed, and shipped in dedicated containers at freezing temperatures. The majority of these tissues are recovered with this aseptic technique of tissue recovery. Contamination can occur during this process or during the transfer to the containers before arriving at the tissue bank. This aseptic technique should not be considered a sterile process. Contamination has been documented to come from the donor’s gastrointestinal or respiratory tract (agonal contamination).10,12 Recent outbreaks have documented this contamination after death with the breakdown of the gastrointestinal system as well as recovery after asystole at late times outside tissue banking standards.23

Tissue banks examine the bioburden of the tissue surface and the accompanying tissue fluid of received tissues. Bioburden is defined as the number of contaminated organisms found in a given amount of material before undergoing a sterilizing procedure. Allograft tissue has a complex physical surface with cracks and fissures that make removal of all potential pathogens difficult. Surface swab cultures are documented to be only 70% to 92% sensitive.26 The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention,18 the medical industry standard for sterility testing and other quality control procedures, has stated that swab cultures should not be used for definitive evidence of sterilization. Cultures should be used to monitor previously validated sterilizing processes. Some tissue banks will reject tissues if there is a large amount of bioburden when they initially receive the tissue.

When processing tissue, the tissue banks strive to clean and sterilize tissue for transplantation. Sterilization is defined as a process that kills all forms of life, especially microorganisms. Sterility has been expressed as a mathematical probability of risk. The FDA has established a sterility insurance level (SAL) 10–3 as adequate for implantable medical biologic devices. This means that there is a 1 in 1000 chance (probability) that a living viable microbe can exist in or on the implantable device. Conventional musculoskeletal allografts are routinely classified as HCT/P by the FDA/Center for Biologics Evaluation in Research (CBER). The Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI)4 states that an SAL of 10–6 is appropriate for medical devices. Currently, the AATB requires an SAL of 10–6 as their standard, different from that of the FDA.3

The FDA is the ultimate governing body over the tissue banking industry but does not specifically state which sterilization processing technique is the best or which should be used. Within the recent rules for GTP, the FDA requires that any tissue banking establishment that makes a written statement of allograft sterility with their labeling will be subject to surprise inspections and review by the FDA.19,22 Each tissue bank must have validated data for their statements of sterility by their individual tissue processing method. Most tissue banks use a proprietary formula of different biologic detergents, alcohol, antibiotics, and hydrogen peroxide.

Table 9–1 lists examples of a few of the major tissue bank processes including formulas such as Allowash XG by Lifenet, which uses a scrubbing technique and intensive decontamination steps with alcohol, antibiotics, and hydrogen peroxide. The BioCleanse tissue process from Regeneration Technologies, Inc. (RTI), uses a vacuum-pressure low-temperature automated process with hydrogen peroxide and alcohol. The Musculoskeletal Transplantation Foundation (MTF) uses an allograft tissue purification process (ATP), a nonconic detergent, hydrogen peroxide, and alcohol process with an antibiotic cocktail. Tissue Bank International (TBI) has TranZgraft, a proprietary sterilizing process used at low temperature. Allosource uses Validated Sterilizer as a disinfection process. These tissue banks have validated their individual proprietary sterilizing processes to an SAL level of 10–6

TABLE 9-1 Major Tissue Banks and Their Current Sterilization Methods

| Tissue Bank | Sterilization Method |

|---|---|

| AlloSource | SterileR: validated bioburden reduction cleansing system followed by low-dose terminal irradiation to provide SAL 10–6. Package is labeled “sterile.” |

| Bone Bank Allografts | GraftCleanse: proprietary blend of cleansing agents used to reduce bioburden and provide aesthetic white appearance. GraftCleanse: terminal low-dose gamma irradiation achieves package sterility. |

| Community Tissue Services (CTS) | Musculoskeletal grafts are soaked and rinsed in antibiotics, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, sterile water, and AlloWash solutions. Low-dose terminal gamma irradiation is used to eliminate most bacteria. |

| LifeNet | AlloWash XG: rigorous cleansing removes blood elements, followed by decontamination and a scrubbing regimen to eliminate bacteria and viruses. Tissue is terminally irradiated at a low dose to reach SAL 10–6 and is labeled “sterile.” |

| Musculoskeletal Tissue Foundation (MTF) | MTF processes soft tissue allografts aseptically and treats the grafts with an antibiotic cocktail of gentamicin, amphotericin B, and imipenem and cilastin sodium (Primaxin). Some incoming tissue is pretreated with low-dose gamma irradiation to reduce bioburden. No terminal irradiation is used. |

| OsteoTech | OsteoTech processes allograft tissue using aseptic technique in class 100 clean rooms. Isolators are used to prevent cross-contamination. |

| RTI Biologics, Inc. | BioCleanse: an automated chemical sterilization process that is validated to remove blood, marrow, and lipids and eliminate bacteria, fungi, spores, and viruses while maintaining biomechanical integrity and biocompatibility. No preprocessing or terminal irradiation is used on sports medicine allografts. All tissue reaches SAL 10–6 after BioCleanse. |

| Tissue Banks International (TBI) | Clearant Process: pathogen inactivation process involving high-dose gamma irradiation at (5.0 Mrad) combined with radioprotectant that sterilizes tissue in the final packaging and significantly inactivates infectious agents and maintains the function of the allograft. Process yields SAL 10–6 and package is labeled “sterile.” |

SAL, sterility insurance level.

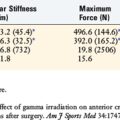

Gamma radiation is a very effective sterilization agent that generates free radicals, which can adversely affect the structure of collagen. Higher doses of radiation have been documented to be deleterious to the tissue, and at this time, low-dose radiation is commonly used by tissue banks to remove surface contaminants.6,9

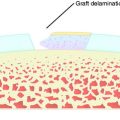

Step Three: Packaging and Terminal Sterilization

The last step of preparation before tissues are distributed for implantation involves packaging and terminal sterilization. All tissue banks are concerned with the handling of the graft after the tissue cleaning process. This packaging process can involve human contact in a clean room and can be a source of infection. To remove concerns about this contamination, terminal sterilization is the final processing step to prepare tissues for shipping in their prepared packages. Two methods are used to terminally sterilize tissue: (1) Ethylene oxide (ETO) gas has fallen out of favor because of documented host tissue reactions with ETO-treated grafts. (2) Gamma radiation is most commonly used at low doses. These lower doses of radiation are believed to not mechanically harm the tissue and are effective in removing any low-dose bioburden in or on the tissue. It is very easy to irradiate tissue after packaging, and this is done in the frozen state at two major centers in the United States.24,26

Tissue banks label their packaged allografts in different ways. Some put the age of the graft and some claim sterility on the packaging. With new GTP regulations, any label claims are subject to FDA scrutiny, and as noted previously, tissue banks must have validated justifications for any label claims.19 The medical director of each tissue bank has a critically important position to monitor and document all regulatory issues. This director oversees the inspection of the tissues, quality control, and tissue processing at the tissue bank.24

After processing, packaging, and terminal sterilization are complete, most allograft tissues are stored frozen. All accredited tissue banks follow common storage guidelines specified by the AATB.3 The tissue is also kept frozen during overnight shipping and delivering to the end user at the point of surgery. Hospitals, surgery centers, and other organizations continue to maintain the graft frozen in storage prior to implantation.

SUMMARY

As newer sterilization processes for allograft human tissues are developed, their in vivo biologic and biomechanical effects need to be evaluated. The AAOS recommends that surgeons use AATB member banks.1 Surgeons need to be familiar with the processing of allograft tissue and know the tissue banks with which they work. Routine culture of the allograft tissue out of the package in the operating room is not necessary because it has been documented that these swab

cultures are not only inaccurate but also a minor source of contamination compared with the operation itself. There is a growing emphasis on monitoring these individual tissues on a national website. Adverse events need to be reported to all health personnel, further emphasizing the importance of the relationship between the tissue banks and the health care providers.

1 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Advisory Statement #1011: Use of musculoskeletal tissue allografts. Available at http://www.aaos.org/wordhtm/papers/advistm/allograf.htm

2 American Association of Blood Banks: Guidelines for managing tissues allografts in hospitals. Available at http://www.aabb.org

3 American Association of Tissue Banks: Standards for Tissue Banking, 11th ed. McLean, VA: AATB, 2006. Available at www.aatb.org

4 Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. Sterilization of health care products—radiation—part 1: requirements for the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices. Arlington, VA: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, 2006. AAMI/ISO 11137-12

5 Buck B.E., Malinin T.I. Human bone and tissue allografts. Preparation and safety. Clin Orthop. 1994;303:8-17.

6 Curran A.R., Adams D.J., Gill J.L., et al. The biomechanical effects of low-dose irradiation on bone–patellar tendon–bone allografts. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1131-1135.

7 Dodd R.Y., Notari E.P.4th, Stramer S.L. Current prevalence and incidence of infectious disease markers and estimated window-period risk in the American Red Cross blood donor population. Transfusion. 2002;42:975-979.

8 Fang C.T., Chambers L.A., Kennedy J., et alAmerican Red Cross Regional Blood Centers: Detection of bacterial contamination in apheresis platelet products. American Red Cross experience, 2004. and the. Transfusion. 2005;45:1845-1852.

9 Fideler B.M., Vangsness C.T.Jr., Moore T., et al. Effects of gamma irradiation on the human immunodeficiency virus. A study in frozen human bone–patellar ligament–bone grafts obtained from infected cadavers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1032-1035.

10 Finegold S.M., Attebery H.R., Sutter V.L. Effect of diet on human fecal flora: comparison of Japanese and American diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27:1456-1469.

11 Gocke D.J. Tissue donor selection and safety. Clin Orthop. 2005;135:17-21.

12 Hirn M.Y., Salmela P.M., Vuento R.E. High-pressure saline washing of allografts reduces bacterial contamination. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:83-85.

13 Joint Commission on Accreditation on Health Care Organizations. http://www.jcaho.org. New Standards PC, 17, 20 and PC 17, 20. Available at(accessed September 9, 2006)

14 McAllister D.R., Joyce M.J., Mann B.J., Vangsness C.T.Jr. Allograft update—the current status of tissue regulation, procurement, processing, and sterilization. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:2148-2158.

15 NNIS System, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Service. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004. data summary from January 1992 through June 2004

16 Srinivasan A. Epidemiology of organ- and tissue-transmitted infections. Presented at Workshop on Preventing Organ- and Tissue Allograft-Transmitted Infection: Priorities for Public Health Intervention June 2 2005. Atlanta. Proceedings available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/bbp/organ-tissueWorkshop_June2005.pdf

17 Strong D.M., Katz L. Blood-bank testing for infectious diseases: how safe is blood transfusion? Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:355-358.

18 United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Sterilization and sterility assurance of compendial articles. Chapter 1211. In United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary (USP25-NF20). Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc.; 2002.

19 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Current good tissue practice for manufacturers of human cellular- and tissue-based products establishments: inspection and enforcement: proposed rule. Fed Reg. 2001;66:1508-1559. Jan 8; Available at http://www.fda.gov/cber/tiss/htm

20 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Current good tissue practice for human cell, tissue, and cellular- and tissue-based product establishments: inspection and enforcement; Final Rule 21 CFR Parts 16, 1270, and 1271 (D,E,F) 69. Fed Reg:16-611-68688. www.fda.gov/cber/tiss/htm, November 24, 2004. Available at

21 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft document guidance for industry: preventive measures to reduce the possible risk of transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) and variant Creuzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) by human cells, tissues and cellular- and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps). http://www.fda.gov/cber/tiss/htm, June 14, 2002. Available at

22 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry: eligibility determination for donors of human cells, and tissues and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps). http://www.fda.gov/cber/tiss/htm, 2004. May . Available at

23 Vangsness C.T.Jr., Garcia I.A., Mills C.R., et al. Allograft transplantation in the knee: tissue regulation, procurement, processing, and sterilization. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:474-481.

24 Vangsness C.T.Jr., Wagner P.P., Moore T.M., Roberts M.R. Overview of safety issues concerning the preparation and processing of soft-tissue allografts. J Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1351-1358.

25 Vangsness C.T.Jr. Soft-tissue allograft processing controversies. J Knee Surg. 2006;19:215-219.

26 Veen M.R., Bloem R.M., Petit P.L. Sensitivity and negative predictive value of swab cultures in musculoskeletal allograft procurement. Clin Orthop. 1994;300:259-263.

27 Zou S., Dodd R.Y., Stramer S.L., Strong D.M., Tissue Safety Study Group. Probability of viremia with HBV, HCV, HIV, and HTLV among tissue donors in the United States. and the. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:751-759.