CHAPTER 14 Alimentary tract

Oesophagus

Most conditions of the oesophagus have dysphagia as a symptom. Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. It may result from local or general causes (→ Table 14.1).

| Local | |

| In the lumen | Foreign body |

| In the wall | Congenital atresia |

| Inflammatory stricture – reflux oesophagitis | |

| Caustic stricture | |

| Achalasia | |

| Carcinoma | |

| Plummer–Vinson syndrome (oesophageal web) | |

| Scleroderma | |

| Irradiation | |

| Outside the wall | Mediastinal lymphadenopathy |

| Bronchial carcinoma | |

| Retrosternal goitre | |

| Pharyngeal pouch | |

| Para-oesophageal (rolling) hiatus hernia | |

| Thoracic aortic aneurysm | |

| Dysphagia lusoria (vascular ring) | |

| General | Myasthenia gravis |

| Bulbar palsy | |

| Bulbar poliomyelitis | |

| Hysteria |

Inflammatory stricture

Hiatus hernia

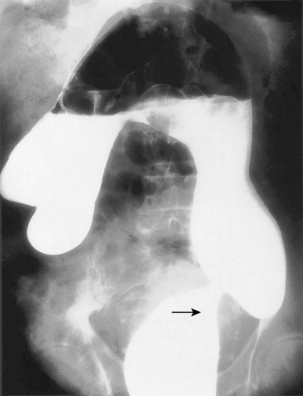

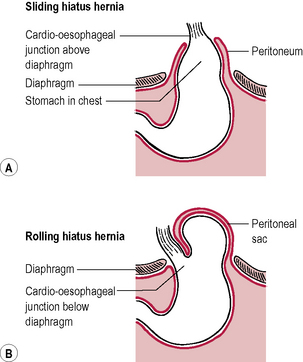

There are two types: sliding (90%) and rolling or paraoesophageal (10%). In the rolling type, the cardio-oesophageal mechanism is intact and therefore reflux does not occur. The stomach rolls up alongside the lower oesophagus pressing on it and causing dysphagia (→ Fig. 14.1).

Sliding hiatus hernia

The stomach slides through the hiatus and therefore the position of the cardio-oesophageal junction changes and reflux occurs (→ Fig. 14.1).

Investigations

Treatment

Surgical

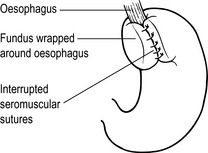

Indicated for failed medical treatment or complications, e.g. anaemia or severe dysphagia due to stricture. Surgery may also be indicated for young patients who do not want to take long-term acid-suppressant agents. There are several operations but a Nissen fundoplication (→ Fig. 14.3) is the most commonly performed. The hernial defect is repaired and the mobilized fundus of the stomach is wrapped around the lower end of the oesophagus to provide an antireflux mechanism. This may be done by the ‘open’ or laparoscopic method.

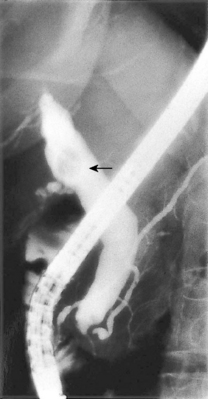

Achalasia

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Stomach and duodenum

Peptic ulceration

Investigations

Treatment

Medical

Surgical

Indications are the following:

Carcinoma of the stomach

Gastric surgery and its complications

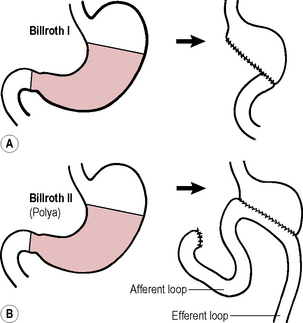

Operations

Complications

Bilious vomiting

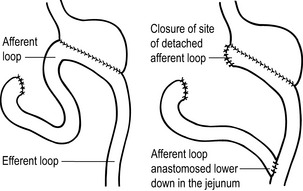

Sudden emptying of the afferent loop with Billroth II. Associated biliary gastritis. May respond to metoclopramide. Severe cases need revisional surgery, e.g. Roux-en-Y anastomosis so that bile enters the GI tract lower down in the jejunum (→ Fig. 14.6).

Dumping

Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding

Conditions of the small bowel

Small bowel obstruction

Causes

Investigations

Appendicitis

Investigations

Differential diagnosis

In the atypical case, other causes of intra-abdominal pathology, urinary tract disease, gynaecological problems (see Ch. 22) and extra-abdominal conditions must be considered.

Conditions of the colon, rectum and anus

Colonic polyps

Hamartomas

Colorectal cancer

There are two types of autosomal dominant hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC):

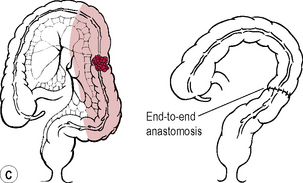

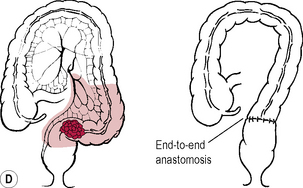

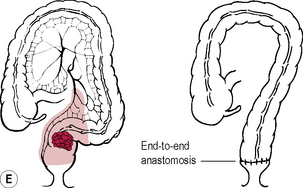

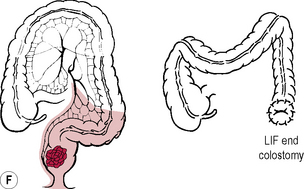

Treatment

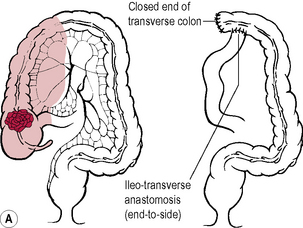

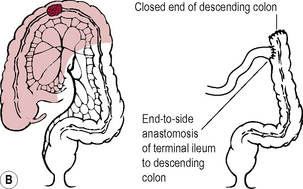

Elective

Prognosis

This is based on Dukes’ classification, originally described for rectal cancer but now applied to all colorectal adenocarcinomas (→ Table 14.2).

| A | Confined to bowel wall; 80% 5-year survival |

| B | Through wall into surrounding tissue; 60% 5-year survival |

| C | Lymph node involvement; 30% 5-year survival |

a If distant metastases are present, the 5-year survival is only 5%.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Crohn’s disease

Ulcerative colitis

Investigations

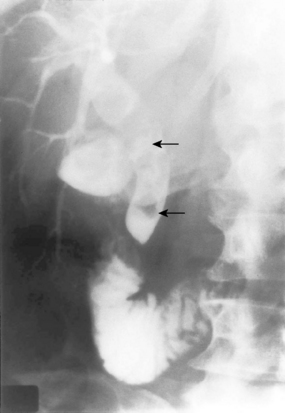

Diverticular disease

Treatment

Uncomplicated, symptomatic diverticular disease

High-fibre diet. Antispasmodic, e.g. Colofac. Bulking agent, e.g. Fybogel.

Perforation with generalized faecal peritonitis

Laparotomy. Peritoneal lavage. Resect perforated area. In case of sigmoid diverticulae treatment is by Hartmann’s procedure (see Procedures box at end of chapter). Drain peritoneal cavity. Antibiotics as for acute diverticulitis. In the elderly, perforated diverticulitis with faecal peritonitis carries a high mortality.

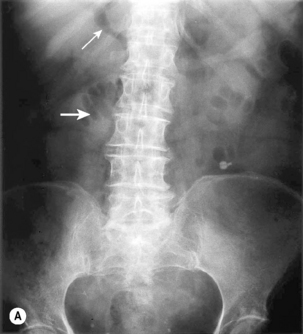

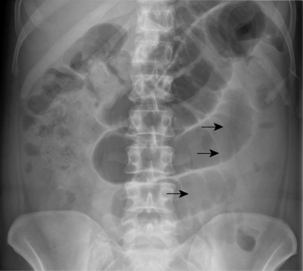

Volvulus

Sigmoid volvulus

Investigations

Anal conditions

Haemorrhoids

Investigations

Treatment

Fissure-in-ano

Fistula-in-ano

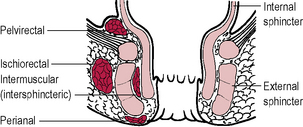

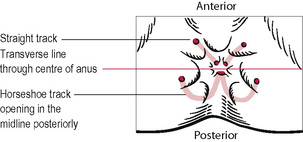

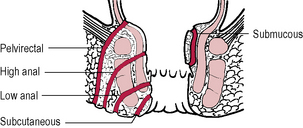

A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelial surfaces. In this instance, there is an internal opening in the anal canal and one or more external openings on the perianal skin. Most arise from delay in treatment, or inadequate treatment, of anorectal abscesses. Rarer causes include Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis and carcinoma. It may be difficult to locate the internal opening. Application of Goodsall’s rule (‘if the external opening lies anterior to a line drawn transversely through the centre of the anus, the track passes radially through a straight line towards the internal opening. If the external opening is behind this line the track curves in a horseshoe manner to open into the midline posteriorly’) (→ Fig. 14.17). Fistulae may be classified as subcutaneous, submucous, low anal (below puborectalis), high anal (opening in close relation to the anorectal junction) or pelvirectal (penetrating levator ani) (→ Fig. 14.18).

Rectal bleeding

Bleeding PR is a common clinical problem. The commonest causes are haemorrhoids, fissure-in-ano and colorectal cancer. Massive rectal bleeding may be due to diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, or a cause in the upper GI tract, e.g. peptic ulcer or an aorto-enteric fistula. If bright red rectal haemorrhage is coming from the upper GI tract, the bleeding is massive with rapid gut transit time and the patient will always be shocked. (For causes of rectal bleeding → Table 14.3.)

| Haemorrhoids |

| Fissure-in-ano |

| Carcinoma of anus |

| Colorectal carcinoma |

| Colorectal polyps |

| Diverticular disease |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

Liver

Diseases of the liver usually present to the surgeon as jaundice, hepatomegaly, or ascites. This section will deal only with liver disease as far as it concerns the surgeon. (For causes of hepatomegaly → Table 14.4.)

| Regular generalized enlargement without jaundice | Cirrhosis |

| Congestive cardiac failure | |

| Reticuloses | |

| Budd–Chiari syndrome (hepatic vein obstruction) | |

| Amyloid | |

| Regular generalized enlargement with jaundice | Viral hepatitis |

| Biliary tract obstruction | |

| Cholangitis | |

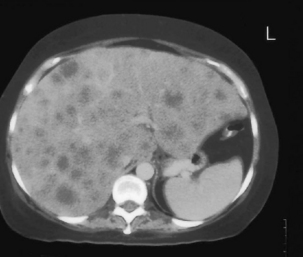

| Irregular generalized enlargement without jaundice | Secondary tumours |

| Macronodular cirrhosis | |

| Polycystic disease | |

| Primary tumours | |

| Irregular generalized enlargement with jaundice | Cirrhosis |

| Widespread liver secondaries | |

| Localized swellings | Riedel’s lobe |

| Hydatid cyst | |

| Amoebic abscess | |

| Primary carcinoma |

Infections in the liver

Abscess

This is rare and usually caused by pyogenic bacteria. Causes are due to the following:

Liver tumours

Primary malignant tumours

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Symptoms and signs

Pre-existing cirrhosis. Abdominal pain. Weight loss. Fever. Ascites. Jaundice. Hepatomegaly.

Portal hypertension

Treatment of bleeding oesophageal varices

Acute bleed

Definitive treatment after bleeding

Extrahepatic biliary system

Cholelithiasis (gallstones)

About 80% of stones are asymptomatic. Symptoms are related to the complications they cause.

Empyema

Gallstone ileus

Obstructive jaundice

Investigations

Pancreas

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

Investigations

Tumours of the pancreas

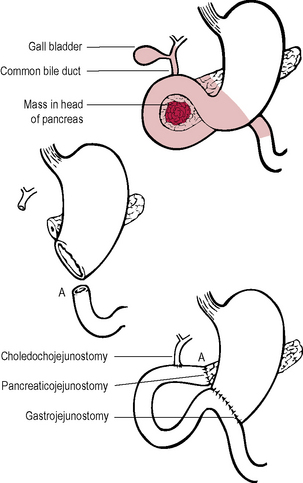

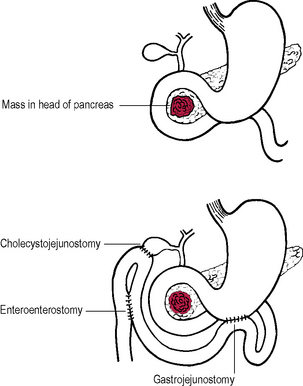

Carcinoma of the pancreas

Treatment

Spleen

Splenomegaly

The spleen must be enlarged to about three times its normal size before it becomes clinically palpable. The lower margin may feel notched to palpation. It may become so large that it is palpable in the RIF. Massive splenomegaly in the UK is likely to be due to CML, myelofibrosis or lymphoma. Splenomegaly may lead to hypersplenism, i.e. pancytopenia as cells become trapped in an overactive spleen and are destroyed. Anaemia, infection, or haemorrhage may result. (For causes of splenomegaly → Table 14.5.)

| Infective | |

| Bacterial | Typhoid |

| Typhus | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Septicaemia | |

| Abscess | |

| Viral | Glandular fever |

| Spirochaetal | Syphilis |

| Leptospirosis | |

| Protozoal | Malaria |

| Parasitic | Hydatid cyst |

| Inflammatory | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Sarcoid | |

| Lupus | |

| Amyloid | |

| Neoplastic | Leukaemia |

| Lymphoma | |

| Polycythaemia vera | |

| Myelofibrosis | |

| Primary tumours | |

| Metastases | |

| Haemolytic disease | Spherocytosis |

| Acquired haemolytic anaemia | |

| Thrombocytopenic purpura | |

| Storage diseases | Gaucher’s disease |

| Deficiency diseases | Pernicious anaemia |

| Severe iron deficiency anaemia | |

| Splenic vein hypertension | Cirrhosis |

| Splenic vein thrombosis | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |

| Non-parasitic cysts |

In infants, diarrhoea and vomiting may be the only symptoms. This may lead to difficulty in diagnosis and confusion with gastroenteritis. In elderly patients there may be confusion and later, shock may develop.

In infants, diarrhoea and vomiting may be the only symptoms. This may lead to difficulty in diagnosis and confusion with gastroenteritis. In elderly patients there may be confusion and later, shock may develop.