27 Airway Block Anatomy

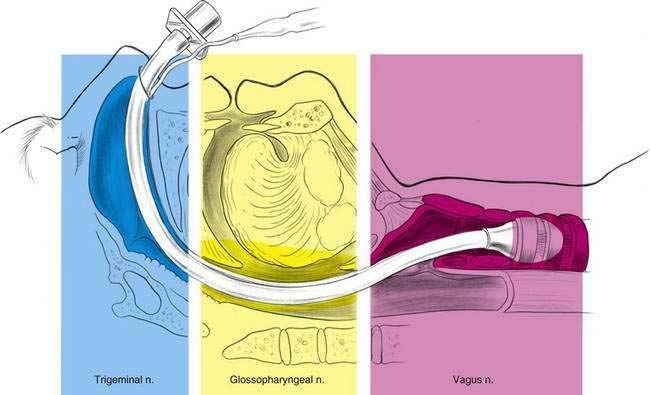

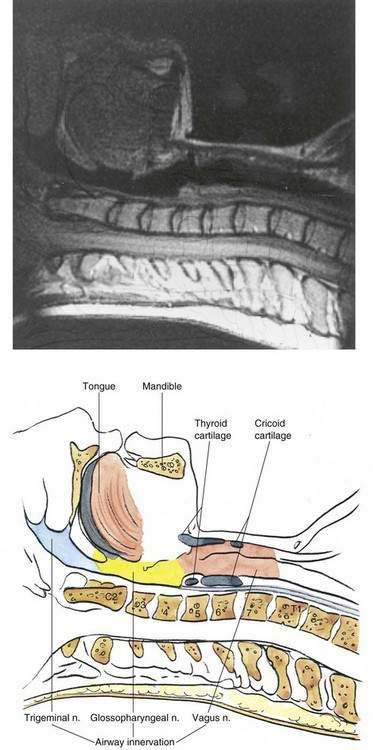

If there is one set of regional blocks that an anesthesiologist should master, it is airway blocks. Even those anesthesiologists who prefer to use general anesthesia for the majority of their cases will be faced with the need to provide airway blocks before anesthetic induction in patients who may have airway compromise, trauma to the upper airway, or unstable cervical vertebrae. As illustrated in Figure 27-1, innervation of the airway can be separated into three principal neural pathways: trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, and vagus. If nasal intubation is planned, some method of anesthetizing the maxillary branches from the trigeminal nerve will need to be carried out. As our manipulations involve the pharynx and posterior third of the tongue, glossopharyngeal block will be required. Structures more distal in the airway to the epiglottis will require block of vagal branches.

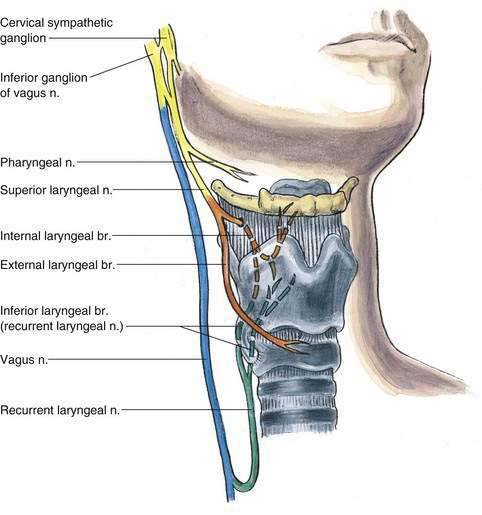

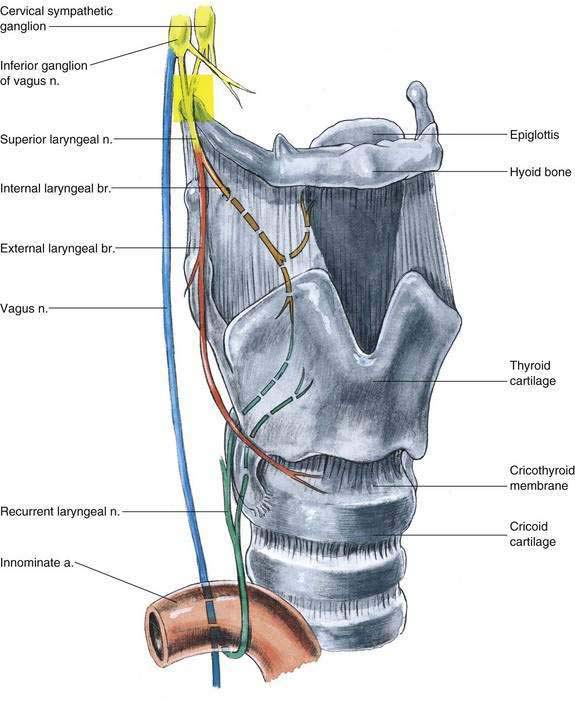

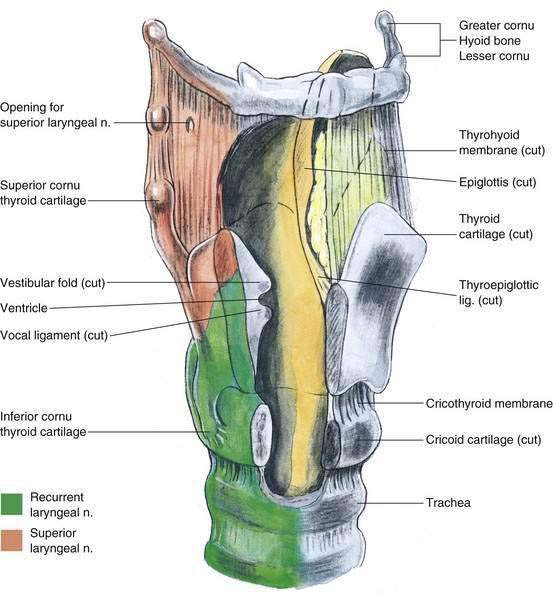

The vagus nerve supplies innervation to the mucosa of the airway from the level of the epiglottis to the distal airways, through both the superior and the recurrent laryngeal nerves, as illustrated in Figures 27-2 and 27-3. Although the vagus is primarily a parasympathetic nerve, it also contains some fibers from the cervical sympathetic chain, as well as motor fibers to laryngeal muscles. The superior laryngeal nerve provides sensation to the surfaces of the epiglottis and to the airway mucosa to the level of the vocal cords. It provides innervation to the mucosa after entering the thyrohyoid membrane just inferior to the hyoid bone between the greater and the lesser cornua of the hyoid. This mucosal innervation is carried out through the internal laryngeal nerve, a branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The superior laryngeal nerve also continues as the external laryngeal nerve along the exterior of the larynx; it provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle.

The recurrent laryngeal nerve is a branch of the vagus nerve that ascends along the posterolateral margin of the trachea after looping under the right subclavian artery as it leaves the vagus nerve on the right, or around the left side of the arch of the aorta, lateral to the ligamentum arteriosum, on the left. The recurrent nerves ascend and innervate the larynx and the trachea caudal to the vocal cords. This anatomy is illustrated in Figures 27-2, 27-3, and 27-4. Figure 27-5 shows a sagittal magnetic resonance image with an interpretive illustration of airway innervation keyed to the colors used in Figure 27-1.